Enter the Dragon: The Evolution of Dragons

To conclude our journey in honor of the Year of the Dragon, a look into the transformation of the relationship between humans and dragons until today

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

Apr 26, 2024

Dragons aren’t what they used to be. The glorious paleolithic dragon of lightning and wildfire was a fearsome and untamable beast who must be tolerated in its power and glory. This primordial monster became the servant of the king in Sumerian culture as the solid innovations of city and state pushed nature away and resisted the dragon’s power. Stories of the giant naga snakes of steamy India traveled West to ancient Greece and North-East to China, savage and sensual partners and protectors of the dryads. The Romans adapted the Greek stories, and when they became Christians, the dragons became evil, and this narrative dominated the character of Western dragons for a millennium and a half.

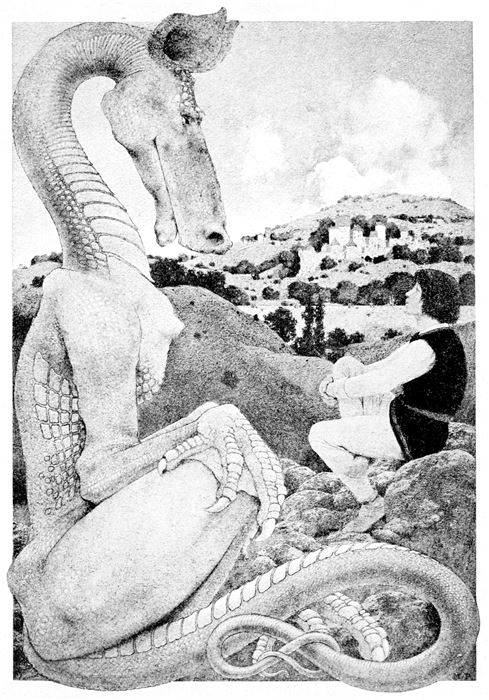

At the end of the 19th century weakened dragons took a sad turn into being the pathetic companions of children in Kenneth Grahame’s popular 1898 story The Reluctant Dragon, in which a boy became friends with the monster, who was a pacifist and refused to battle St. George when he was summoned by the blustering and cowardly villagers. The boy, St. George, and the dragon staged a fake fight, and everybody lived happily ever after – the dragon recited his poetry at a feast, and the villagers admired his friendly wit, accepting him. The dragon was drawn beautifully by American artist Maxfield Parrish, who gave him a dumpy anthropomorphic body and a goofy, long-snouted head. Grahame’s story set an enduring trend of stories of gentle dragons written for young readers, and his story was made into a Disney movie in 1941.

Illustration to The Reluctant Dragon in Dream Days

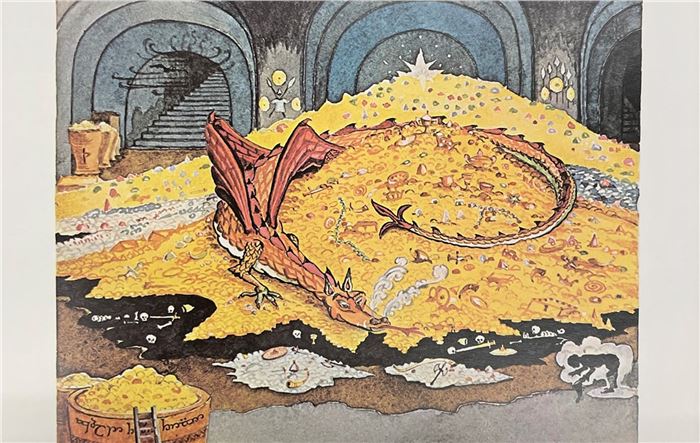

J.R.R. Tolkien wisely warned against such trivialization, warning, “Never laugh at live dragons.”

In his The Hobbit, Smaug was a covetous thief of gold and jewels. In Middle Earth, dragons were miserly hoarders who produced nothing – they were wasters and destroyers of landscapes. When Smaug flew South to invade the Lonely Mountain there was, “a noise like a hurricane coming from the North, and the pine-trees on the Mountain creaking and cracking in the wind,” and the dragon settled on the mountain in a fountain of flame, incinerating the woods, boiling the river, burning the dwarves, and seizing their treasure. When Bilbo Baggins crept into the halls under the mountain, he found red and gold Smaug sleeping on vast mounds of treasure, with bat-like wings folded, smoke drifting from his nostrils, and his belly crusted with gems, jewels and gold. Bilbo stole a cup from the immense hoard, and the greedy dragon knew at once, and was provoked to fury and consumed by his desire to obliterate the thief. Obsessed, Smaug smashed the mountainside, and flew in flames over the nearby town, where the slayer, Bard, waited with his black arrow, and loosed into the weakness of the dragon’s scaly armor. Pierced, the dragon fell onto the town, destroying it. In the aftermath five armies fought over the hoard. Sinful greed and covetousness dominated the story. Tolkien was his own illustrator, and created a famous portrait of Smaug sleeping on his fabulous hoard. Tolkien’s Smaug was a classic monster of Christian myth – a throwback among dragons, and The Hobbit another story for children.

A new kind of dragon emerged when a literary revival at the turn of the 1970s rejected the tiresome trope of young children’s storybook dragons cast in weak roles as the eunuch friends of kids. Science fiction writer Anne McCaffery’s 1968 novel Dragonflight re-established the dragon genre for young adult readers, popularizing stories of youths meeting and befriending dragons. She imagined genetically modified telepathic fire-blowers ridden by bonded youths selected for their mind-melding abilities and wrote a stream of dragon tales throughout the coming decades. But Michael Whelan’s pictures for the book turned dragons into flying dinosaurs, and these were still dragons for children, allegories of adolescence.

Anne McCaffery’s 1968 novel Dragonflight

Ursula K. Le Guin introduced her dragon Yevaud in the first book of the Earthsea trilogy (adequately but unexcitingly illustrated by Charles Vess) The Wizard of Earthsea, that book was a coming-of-age story about a boy maturing as a wizard and had little to do with the dragon, who followed the greedy pattern of Smaug, and continued the role of dragons in immature fantasies. In The Farthest Shore, published in 1972, the dragon Orm Embar co-operated with the heroes who resisted an evil wizard, Cob, who made the false promise of life after death to his followers and was responsible for magic fading throughout the world. In a reversal of the good versus evil Christian tradition of two millennia, the heroic dragon Orm Embar died while killing the evil Cob.

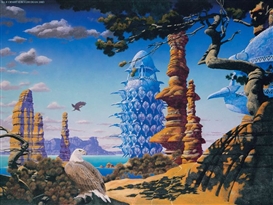

Roger Dean is the most influential living dragon artist. His paintings are especially interesting as examples of the evolution of dragons in the past fifty years, and their restoration of the allegorical monsters to the province of adults. As much as he admired Tolkien and was inspired by him, Dean wasn’t impressed by Smaug. “My main impression of Smaug was that he slept and was grumpy.” Dean wanted to change the violent narrative of envy and renew the co-operation between humans and dragons he learned from feng shui but avoid the childish sentimentality of Kenneth Grahame’s story. His work sought to restore the dragons to the lost balance of the dao.

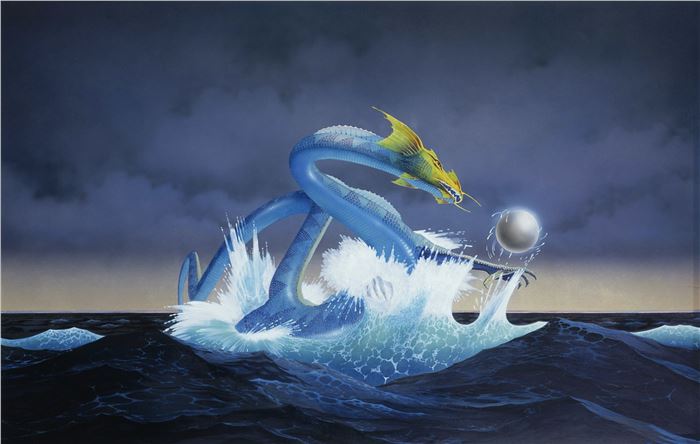

His dragons were a dramatic re-imagining. Dean commented, “I think the whole notion of dragons as the enemy came about not from the origins of dragons but from the origins of Christianity… Dragons are about power and wisdom. They’re fascinating in all oriental mythology, especially Chinese. They’re not symbols of evil at all.” He looked East for inspiration. European dragons were dangerous creatures that must be destroyed if the dragon slayer was to possess the treasure they guarded, but Chinese dragons represented the great principle that – in balance with the tiger of the female principle – shaped nature. The Western impulse to slay the immortal dragon of the dao was to upset the natural balance of ying and yang that governs the earth. “The tiger and the dragon are ancient symbols of yin and yang,” Dean commented, “The dragon represents the creative, reigning over the heavens, and the tiger has earth as its territory.”

By 1982, Dean had refined his dragons into fully-fledged creatures of his elemental world. He imagined how dragons might live and painted a gorgeous red Fire Dragon as it played with flying fish leaping a waterfall. Dean explained, “The fish are dancing because of their proximity, they’re the dragon’s ancestors.” His dragons were no lumbering and leathery dinosaurs. He gave them the streamlined silhouettes of silver fish, and shimmering skins of rainbow hues, complex coats of psychedelic camouflage. His dragons were fast, writhing creatures of the water, and hunters in the heights.

He successfully changed the perception of dragons. Dean’s restoration of dragons to their mature place of power and beauty made possible the tortured and imprisoned Ironbelly in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Without Dean, the Na'vi natives of utopian Pandora couldn’t have connected to ikran mountain banshees through their feathery and organic neural network. Dean made possible the lethal balance of Daenerys Targaryen’s spectacular dragons as an allegory of dao in Game of Thrones.

To contain their dragons, the Targaryen dynasty constructed a huge arena, containing them and imprisoning them. Over generations, they diminished, until the last of them was the size of a dog. With the diminishment of dragons, the country plunged into the rule of the Mad King and descended into the chaos of civil war and the invasion of the army of the dead. The story can be read as an allegory of imprisoning the Yang of the dao and allowing the tiger Yin to rule freely and without constraint. When Daenerys was in the flow of her rise, leading with the wisdom of experienced yin counsellors to balance her yang instincts for power and authority, the dragons helped her, even dying a doubled death for her cause. But her rule ended when she became a tyrant, and the throne she sought was utterly consumed by the flames of dragon-fire.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page