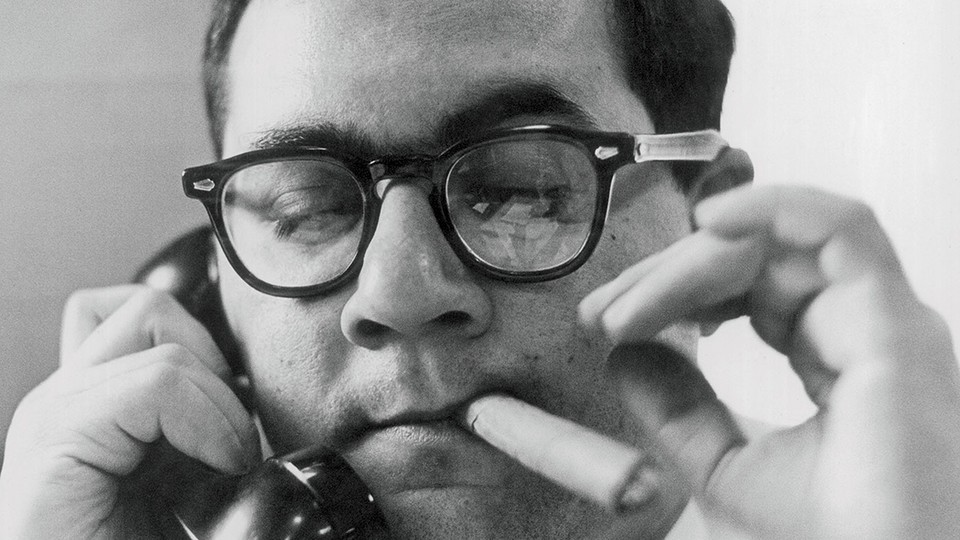

The Cross-Generational Politics of Barney Frank

The Congressman's memoir tackles two of the biggest political shifts of his lifetime: the acceptance of gay people in public life and a dramatic decrease in faith in government.

Since, in his usual way, Barney Frank gets right to the point in his new memoir, I will too: the most engaging—and indeed occasionally heartrending (not an adjective I ever thought I’d use in writing about Frank)—parts of this book are those in which he discusses his long struggles with his sexuality and relationships. He opens by announcing his confusion when, at the age of 14 in 1954, he realized that “I was attracted to the other guys.” At several points he writes of the torment he felt as he also realized how much he hungered to live a political, and thus unusually public, life and what that meant: constant fear, certainly back when he was starting out, that in pursuing such a career, he risked an exposure that would finish him.

And finally, he writes with simple eloquence about finding true love late in life, at age 67, with Jim Ready, whom he married in 2012. A book that begins with his description of the terror he felt at being “an involuntary member of one of America’s most despised groups” closes with an affecting little passage, a kind of auto-benediction, that marks how far both society and Frank have come:

Sixty years ago, when I began to think about how to maximize my participation in politics, I understood that it would require the repression of any private life. Today, I cite the emotional damage I inflicted on myself when I speak with younger LGBT people who ask my advice. It took me far too long to achieve a happy, fulfilling domestic existence … Looking back, I think I was pretty good at my job. Now it is time to be good at life, and with Jim’s help, I think I can be.

It is surprising, as I suggested above, to find oneself being moved by Frank, a man typically described in the press as “brusque” or “acerbic,” and less euphemistically known to be, well, rude. He was never one for small talk. He did not suffer fools patiently. He hated campaigning, as he acknowledges in this book, but the problem seems to have run even deeper. One former aide has spoken about how hard Frank’s staff worked to minimize his campaign schedule, in order to keep him away from as many voters as possible. The more voters he met, his aides’ logic went, the more of them he was likely to alienate.

And yet the man won 16 elections to the House of Representatives, most of them not even close. Once he got in, only two of the remaining 15 were hard fought: his first reelection campaign, in 1982, after his district had been redrawn by state legislators in a way that pitted him against another incumbent, and his 2010 contest, his last, when even Massachusetts came down with a mild case of Tea Party fever. In another six, the GOP didn’t bother to field a candidate. He survived sexual scandal when a male prostitute with whom he’d had a rather unwise and quite painful relationship took his story to the conservative Washington Times in 1989. Through it all, Frank became one of the most respected members of the House and, over time, one of the most powerful: his chairmanship of the House Committee on Financial Services, from 2007 to 2011, gave him authority over the nation’s banking system. Very few who observed Frank at that post, where he helped push through the historic financial-reform legislation that bears his and Senator Chris Dodd’s names, or who watched him jousting with Ken Starr in 1998 or leading the fight on so many LGBT issues, would disagree that he was, without question, pretty good at his job.

Frank has always been a tough one to shove into Washington’s customary ideological pigeonholes. He is, of course, a standard liberal on most issues. But he never had any patience for the left. Growing up in Bayonne, New Jersey, and pumping gas at his father’s truck stop gave him, he writes, experience with and a feel for the struggles of the little guy. Even as a young man, he disapproved of a song popularized by Pete Seeger that in his estimation sneered at working-class housing. (“And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky and they all look just the same,” Seeger sang of postwar homes mass-produced for families like Frank’s.) Frank was a gradualist from the start, and detested demands for purity. “There is a price to pay,” he writes, “for rejecting the partial victories that are typically achieved through political activity.” An earlier book, Speaking Frankly (1992), was mostly one long wag of his finger at the Democratic Party’s paleoliberals.

Frank isn’t, however, a mainline New Democrat type either. The long-held trope among party centrists is that Democrats lost the white working class over cultural issues: “God, guns, and gays.” Frank emphatically rejects this view, instead channeling his inner Elizabeth Warren and making the case that his party’s problems with the white working class are almost wholly economic. “There is no evidence,” he writes, “that any Democrat has lost his or her seat because of support for LGBT rights. Neither is there any evidence that we are being punished for being insufficiently religious.” He acknowledges that guns are a reasonably big deal, but in general, he argues, the voters who have abandoned his party have done so because “they have lost faith in the willingness of Democrats to use the power of government to protect them from hurtful economic trends.”

In these pages as throughout his career, Frank draws clear distinctions between the end goals of politics and the process by which those goals are reached. He’s principled on the former but flexibly pragmatic with regard to the latter, owing no doubt to the lessons he learned early in his career in the hothouse of Massachusetts politics—which, though almost entirely Democratic, is by no means almost entirely liberal. As a young, overworked aide in the late 1960s to the then–mayor of Boston, Kevin White, Frank learned that before you can start changing the world, you have to deal with the existing one. He pushed liberal issues like public-housing integration, and he was also partly responsible for seeing to it that snow got removed. As a state legislator in the 1970s, he coped with a hurdle closer to home: he got into a dispute with the owner of a gay bar who then tried to out him.

Experiences like these will drive home the message that politics is often about merely averting crises and surviving. And if being in Congress for 30-plus years teaches a person anything, it is that you have to be patient and tend to the details: Frank asserts that the one policy area that took up “more of my time and energy than any other issue, including LGBT rights,” was the decidedly unglamorous cause of promoting more rental housing.

But Frank sees the big picture, too, and the great preoccupations of Frank are twin “seismic shifts in American life” that have occurred during his adult lifetime: a dramatic increase in the acceptance of gay people (and of once-ostracized minorities in general), and a simultaneous and also dramatic decrease in faith in government. Frank is not exactly ablaze with fresh insights into these developments, which have been masticated by a thousand social scientists, political professionals, and pundits. But not many people have lived a life like Barney Frank’s, and in this book he draws back the curtain for us in a number of interesting ways.

For starters, he relates some gay political history that is typically left out of the standard narratives. He was for years particularly concerned (for understandable reasons) about a 1953 Eisenhower directive barring homosexuals from ever getting security clearances. Such was the era, Frank writes, that The New York Times, in describing the government witch hunts that preceded the executive order, used the word perverts in its headline. The order, which was backed up by intrusive investigations into private lives, affected countless employees in many different branches of government over the decades. “No federal policy,” Frank writes, “had done us more damage.”

The effects of the directive lasted well beyond the time when many gay men and lesbians started living openly. An order banning the denial of security clearances based on sexual orientation was issued only in 1995; behind President Clinton’s edict lay concerted efforts by Frank, who had become one of the first openly gay members of Congress in 1987. Frank began pushing Clinton on this issue, he writes, after the gays-in-the-military fiasco early in Clinton’s first term, which resulted in a policy—Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell—that left gay activists bitterly disappointed. Certain that Clinton felt badly about the setback, Frank started pressing him to move on other fronts as compensation. In the succeeding years, Frank and Clinton grew quite close; during the Lewinsky saga in particular, Clinton had frequent chats with Frank as his support dwindled. Perhaps Clinton knew that someone who’d survived his own sex scandal would judge him less harshly.

On the question of restoring faith in government, Frank is guardedly hopeful. He argues that many government programs are in fact popular, and that Democrats should expand them. But they have to do so without raising middle-class taxes, so they must cut spending. He singles out two routes: dramatically reducing the military budget by closing some of our far-flung bases and eliminating some missile-delivery systems, and scaling back on the vast amounts of money we spend prosecuting and imprisoning nonviolent drug offenders. These would be heavy political lifts, as he acknowledges. A lot of Democrats would probably prove less than willing to open themselves to simultaneous charges of being soft on defense and soft on crime. Though some signs suggest that times have changed, especially on the criminal-justice-reform front, significant spending reductions in these areas will likely be the work of a generation, at least.

That will be someone else’s job. Frank has done his part. It can’t help looking like well-earned justice that he fell in love at just about the time his state recognized his right to publicly confirm that love. He is more than entitled now to go off and get good at life.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.