Abstract

The cigarette epidemic tends to develop in a similar pattern across diverse populations in different parts of the world. First, the prevalence of smoking increases, then it plateaus and finally it declines. The decline in smoking prevalence tends to be more pronounced in higher social strata. The later stages of the cigarette epidemic are characterized by emerging and persisting socioeconomic gradients in smoking. Due to its detrimental health consequences, smoking has been the subject of extensive research in a broad range of academic disciplines. I draw on literature from both the social and medical sciences in order to develop a model in which physiological nicotine dependence, individual smoking behaviour and norms surrounding smoking in the immediate social environment are related through reflexive processes. I argue that the emergence and persistence of social gradients in smoking at the later stages of the cigarette epidemic can be attributed to a combination of the pharmacological properties of nicotine, network homophily and the unequal distribution of material and non-material resources across social strata.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Owing to a potent combination of immense profitability and fundamental consequences for population health, cigarette smoking has been subject to intense political and scientific battles, involving a range of disciplines, as well as comprehensive legislation (Joossens and Raw 2006; Lock et al. 1998; Mukherjee 2010; Slade 1989). The cigarette epidemic (Lopez et al. 1994; Thun et al. 2012) tends to progress similarly across populations. First, cigarette smoking increases, then it plateaus and finally declines. In populations where smoking has been practised for a longer period, it tends to be more common in lower social strata than in higher social strata. This pattern emerges with remarkable regularity across diverse populations with differing histories, cultures, political orientations, levels of economic development and tobacco control policies.

The social gradient in smoking during the later stages of the cigarette epidemic is then an empirical regularity (Goldthorpe 2000; Merton 1987). Macro-level empirical regularities are generated through the agency of a large number of individuals (Goldthorpe 2016). An appropriate explanation of why and how the social gradient emerges and persists therefore leads us to examine the processes surrounding individual smoking behaviour. The social processes through which individual habitual behaviours, such as smoking, produce and reproduce empirical regularities are outlined in Anthony Giddens’ structuration theory (Giddens 1984). However, since nicotine is an addictive substance, individual smoking behaviour is also shaped by physiological processes, triggered by repeated nicotine exposure.

There are several established theoretical frameworks that address the social gradient of health behaviours in general, for example the health lifestyle theory (Cockerham 2005) and the social resistance framework (Factor et al. 2011). However, individual agency is not only conditional on the external physical and social environment, but also the physiological properties and processes of the body and the specific physiological consequences of health behaviours depend on the health behaviour under consideration. For example, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking and obesity are socially patterned (Hiscock et al. 2012; Pampel et al. 2010; Petrovic et al. 2018), but they affect the body, and by extension the conditions of agency, in separate ways. It is therefore important to consider the specific physiological processes of each behaviour, in this case cigarette smoking. I aim to develop a framework for understanding why social gradients in smoking are a characteristic of later stages of the cigarette epidemic, integrating literature from both medical and social sciences.

The article is outlined as follows. First, I give an account of smoking and tobacco control policies in the later stages of the cigarette epidemic, focusing on the social gradient in smoking. Second, I present a conceptual framework in which I incorporate the pharmacological properties of nicotine and Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory. I argue that nicotine dependence, smoking behaviour and social norms surrounding smoking are related through reflexive processes. Finally, I apply this model to the later stages of the cigarette epidemic and show how a combination of social and biological factors tends to promote social gradients in smoking, regardless of contextual factors.

The later stages of the cigarette epidemic

In a seminal article, Lopez et al. (1994) use historical data to construct a general description of the progression of population patterns of smoking and smoking-related harm. This model is referred to as the cigarette epidemic. Patterns of smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable mortality are defined in several stages. In the first stage, smoking prevalence is low but rising, primarily among men. In the second stage, smoking continues to increase among men and starts to increase among women. In the third stage, damages from smoking start to appear to a substantial degree, and after plateauing, the smoking prevalence begins to decline. Individuals in higher social strata may act as early adopters, taking up smoking to a higher degree in the earlier stages of the cigarette epidemic but the overall decline in smoking prevalence in the later stages tends to be more pronounced in higher social strata. Consequently, the later stages of the cigarette epidemic are further characterized by an emerging and persisting social gradient in smoking (Lopez et al. 1994). The model was later revisited by Thun et al. (2012), who included data from both high- and middle-income countries and found that the overall patterns appear to be similar across countries, though there were more variation in the time lag between men and women than initially assumed by Lopez et al. (1994). The cigarette epidemic is sometimes referred to as the smoking epidemic or the tobacco epidemic.

The smoking prevalence, i.e. the proportion of smokers in a population at a given point in time, is dependent on the rate of smoking initiation and the rate of smoking cessation among smokers, both of which are socially patterned (Bosdriesz et al. 2015; Gilman et al. 2003). The cigarette epidemic unfolds over several decades and different populations are in various stages of the cigarette epidemic. The emergence and persistence of social gradients in smoking are therefore rarely observed in one single study. A study by Legleye et al. (2011) constitutes an exception. The authors are able to capture the emergence and widening of the social gradient in smoking behaviour across birth cohorts in France. The results reveal widening social gradients in smoking initiation among men in successive birth cohorts. Among women, higher rates of smoking initiation are observed in higher social strata in earlier cohorts, while in later cohorts, the gradient is flattened and then reversed. Among both men and women, social gradients in smoking cessation emerge in later cohorts (Legleye et al. 2011).

In the U.S. and other countries where smoking took hold early, the peak and decline of smoking prevalence coincided with the emergence of convincing epidemiological evidence on the link between smoking and lung cancer, e.g. Doll and Hill (1950). Even though the danger of smoking is well known today—smoking was estimated to be responsible for 7.1 million deaths worldwide in 2017 (GBD 2017 Risk Facor Collaborators 2018)—the cigarette epidemic tends to unfold in a similar pattern in populations that initiated smoking at a later time.

Tobacco control policies: medicalization and stigma

The later stages of the cigarette epidemic are also characterized by tobacco control policies. These include a wide range of measures: limiting availability, warning labels, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and establishing non-smoking areas (Berridge 1998; Joossens and Raw 2006). These target smoking behaviour from different perspectives.

Through the process of medicalization, smoking has been increasingly perceived as a medical problem (Rooke 2013). Nicotine dependence in itself is classified as a psychiatric disorder in both the DSM (American Psychiatric Association 2013) and the ICD (World Health Organization 1992). Medical treatments of smoking have focused on reducing the harm from cigarettes, for example through NRT or less harmful nicotine products, rather than targeting nicotine dependence (Rooke 2013). The public health model favours nicotine abstinence over harm reduction, focusing on health education and taxation (Berridge 1998). Within the public health model, smoking is framed as an unhygienic and dangerous habit. Smokers are perceived as individuals of weak moral character, who put others at serious risk through second-hand smoke, but also as rational agents who will chose to quit smoking when educated about the downsides of smoking (Bell 2011; Bell and Dennis 2013; Berridge 1998).

The notion of smoking as dangerous and undesirable is communicated to smokers through warning labels and the physical separation of smokers and non-smokers in public spaces. Smokers often report that they feel excluded and stigmatized (Evans-Polce et al. 2015; Stuber et al. 2008). The framing of smoking as unhygienic and immoral has intensified as smoking became more common in lower social strata (Graham 2012) and in the later stage of the cigarette epidemic, the stigmatization and exclusion of smokers is increasingly associated with social disadvantage (Dennis 2013; Graham 2012).

Tobacco control policies have been suggested to, at least in part, be a reflection of the habits and perceptions of smoking (Brandt 1998), especially in higher social strata (So et al. 2019; Studlar 2008). While stronger tobacco control policies tend to appear alongside a lower prevalence of smokers, they also appear alongside more pronounced social gradients in smoking (So et al. 2019). Several review studies have found that efforts to reduce smoking in the population tend to either exacerbate the social gradient in smoking (in particular non-targeted interventions) or have little effect (Brown et al. 2014; Hill et al. 2014). Increased prices are a notable exception and tend to reduce social differences in smoking (Main et al. 2008).

Besides tobacco control polices, individual smoking behaviour is shaped by other factors that may motivate the individual to smoke. In the following sections, I describe the physiological process of nicotine dependence, the social processes connecting individual smoking with the smoking behaviour of one’s peers, and finally how these are related to each other.

Behavioural and physiological aspects of nicotine dependence

As nicotine enters the body, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) activate in the brain, releasing dopamine, which induces a pleasurable feeling. However, prolonged exposure to nicotine causes the body to develop a tolerance against nicotine and the pleasurable effect diminishes (Benowitz 2010; Dani and Heinemann 1996). Repeated exposure to nicotine desensitizes the nAChRs, while simultaneously causing the body to increase their quantity (Wang and Sun 2005). If the smoker does not maintain a certain level of nicotine, for example through a period of abstinence or simply during the night, the receptors trigger nicotine withdrawal symptoms. This motivates the individual to smoke. Apart from craving nicotine, withdrawal symptoms include several behavioural, psychological and psychosomatic aspects, such as irritability, sleeping difficulties, weight gain, impatience and anxiety (Hughes and Hatsukami 1986).

However, nicotine dependence is not limited to physiological processes and can be described as an interplay between “… pharmacology, learned or conditioned factors, genetics, and social and environmental factors…” (Benowitz 2010, p. 2295). Nicotine dependence can be assessed by questionnaires, for example the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (Heatherton et al. 1991), or by biomarkers such as cotinine levels (Benowitz et al. 2009). Cotinine is released when nicotine is metabolized and can be measured in the blood, saliva or urine (Benowitz et al. 2009). These different types of measure tend to be correlated, although findings on the strength of the correlation are mixed (Muhammad-Kah et al. 2011). Although not everybody who smokes cigarettes develops a physical dependence, heavy smokers and long-term smokers are more likely to develop dependence (Donny and Dierker 2007). Relative to short-term smokers, long-term smokers are both more likely to be nicotine dependent and report that they are smokers in a survey, since they are more likely to smoke at a given point in time. From a population perspective, a larger proportion of smokers is then indicative of a higher prevalence of nicotine dependence.

Graphical representations of the relationship between smoking behaviour and nicotine dependence typically include a feedback loop. Figure 1 is a simplified representation of how this relationship is depicted in the medical literature. It illustrates that smoking and nicotine dependence are mutually reinforcing processes; nicotine dependence increases the individual propensity to smoke. This, in turn, leads to repeated exposure to nicotine and increases the risk of developing nicotine dependence. Processes like these, where cause and effect form feedback loops, are sometimes referred to as reflexive processes.

Habitual smoking and the reproduction of social norms surrounding smoking

Several scholars have argued that rational decision-making processes typically do not characterize habitual behaviours, such as smoking (Cockerham 2005) and Delormier et al. (2009) instead suggest Giddens’ structuration theory as a framework for understanding health behaviour. Giddens (1984) characterizes agency as a flow of conduct and cognition and conduct as intertwined, continuous and simultaneous processes that cannot easily be separated. From this perspective, smoking may be interpreted as a habitual pattern that is continuously performed. This view of agency challenges the notion that agency consists of discrete actions that are outcomes of an internal decision-making process. In everyday life, individuals monitor their own and others’ actions. This forms a common tacit understanding of a given social situation. This knowledge conditions further agency and an unintended consequence of intentional agency is that it modifies these conditions (Giddens 1984). Individuals are knowledgeable agents, who apply this understanding creatively and can transfer their knowledge to new situations. Individual behaviour is then the process through which social norms are reproduced and permeated over time and space, and the process through which they change (Giddens 1984; Sewell Jr 1992). Giddens calls this the duality of structure: “the structural properties of social systems do not exist outside of action but are chronically implicated in its production and reproduction.” (Giddens 1984, p. 374).

There is ample empirical evidence that individual smoking behaviour is conditioned by the smoking behaviour of peers (Seo and Huang 2012; Wellman et al. 2016). For example, Miething et al. (2016) show that the propensity to smoke is higher when the individual has social ties to smokers, and that the propensity to smoke is proportional to the frequency with which the individual interacts with smokers (Miething 2014). Practices surrounding cigarettes and smoking become part of shared and individual identities (Tombor et al. 2013, 2015) and may provide the individual with a sense of belonging. This sense of identity and belonging can act as an incentive to smoke, especially so when smoking is common in the individual’s network. In DiMaggio and Garip’s (2011) terminology, smoking possesses network externalities since “…its value to an actor depends on the number of other actors who consume the product or service or engage in the practice.” (DiMaggio and Garip 2011, p. 1891). From this perspective, smoking behaviour may be interpreted as both a mechanism producing and reproducing the social norms surrounding smoking in the social network.

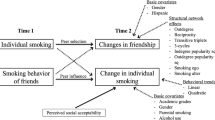

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between smoking and social norms surrounding smoking in the social environment. Social norms are part of the conditions for individual smoking behaviour. Smoking is a habitual pattern that is simultaneously an act of purposive agency and the revision and reproduction of social norms. Smoking behaviour is then related to social norms through a reflexive process.

Habitual smoking, nicotine dependence and social norms as reflexive processes

The social environment and the development of physiological nicotine dependence simultaneously shape individual smoking behaviour. Repeated exposure to nicotine increases the risk for developing nicotine dependence. Individuals who are addicted to nicotine are more likely to smoke. Nicotine dependence may then be interpreted as an unintended consequence of smoking that in turn alters the conditions of further agency. However, through monitoring processes, smoking also modifies social norms which are part of the conditions of further agency. Nicotine dependence and social norms surrounding behaviour smoking, then, constitute both preconditions and consequences of individual smoking behaviour. Both nicotine addiction and social norms regarding smoking are related to individual smoking behaviour through mutually reinforcing, reflexive processes.

This similarity is further emphasized when considering how these processes are depicted graphically. Similarly to how the mutually reinforcing processes of smoking and nicotine dependence are illustrated with feedback loops in the medical literature, Giddens (1984) illustrates the mutually reinforcing processes of monitoring of agency and conditions for individual agency using a feedback loop (see Giddens 1984, p. 5). Figure 3 depicts both these feedback loops using one model, centred on individual smoking behaviour. The grey box signifies the broader social, cultural and institutional context. Individuals are engaged in a range of structures that exist at different levels, operate through different mechanisms and, sometimes, contradict each other (Sewell Jr 1992). For example, while the social norms surrounding smoking in the network are conditioned by the smoking behaviour of the members, all individuals, regardless of their networks, are subjected to the same tobacco control policies and the norms that these express. The figure illustrates that individual agency is embedded in a context and performed using a physical body. Both social and physiological processes simultaneously enable and restrict the scope of agency.

Note that these processes are depicted as simultaneous and across a horizontal, as opposed to a vertical, line. Krieger (2008) argues that graphical depictions within the field of health inequality research perpetuate a limited understanding of the complex relationships between social processes and health (Krieger 2008). In both epidemiology and sociology, graphical representations of individual and structural phenomena are often depicted along vertical lines, implying that these processes are ontologically and temporally ordered. In epidemiology, the upstream–downstream metaphor is used to describe the difference between prevention and treatment. The metaphor describes a river in which there are upstream, or preventive, factors that either cause or prevent an individual from developing a condition and downstream factors, treatments, that come into play once the condition is developed (Krieger 2011). In the case of smoking, both norms and smoking behaviour are the upstream factors that lead to the individual developing nicotine dependence. Likewise in sociology, graphical representations of individual behaviour and social structures, in this case social norms, the social structure, are represented on a vertical axis, with social structures above individual behaviour, for example Coleman’s (1994) boat. Giddens’ (1984) argument that the structural properties of social systems are not ontologically or temporally separated from individual agency can be extended to include biological processes taking place at a cellular level within the physical bodies of participating individuals. Contextual factors, for example tobacco control policies and societal norms surrounding smoking, are directly implicated in individual agency through pricing, warning labels and designated non-smoking areas. The representation in Fig. 3 places biological, behavioural and contextual factors on the same axis in order to illustrate that biological, behavioural and structural processes are integrated and simultaneous.

Why are those in lower social strata more likely to smoke?

So far, I have argued that individual smoking behaviour is reflexively related to social norms surrounding smoking in the social network as well as to physiological nicotine dependence. The combination of social norms and nicotine dependence contributes to the persistence of smoking patterns within social networks. Since individuals tend to form social ties with others in the same social strata more often than with individuals in different strata (DiMaggio and Garip 2011; McPherson et al. 2001), these processes contribute to the persistence of differences in smoking behaviour between social strata. For example, Lorant et al. (2017) found that both network homophily and peer smoking status contribute to social inequalities in adolescent smoking in six European countries. The combination of network homophily and nicotine dependence may then contribute to the persistence of social gradients in smoking but this does not in itself explain why social gradients emerge. In the following sections, I will seek to provide an account of why it is individuals in lower social strata who are more likely to smoke compared to those in higher social strata, rather than the other way around, specifically during the later stages of the cigarette epidemic.

Nicotine as a form of self-medication

The medical literature describes smoking as a form of self-medication used to avoid nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Benowitz 2010; Dani and Heinemann 1996). Some stress-related disorders and nicotine withdrawal symptoms partly overlap, for example irritability and anxiety (Kassel et al. 2003; Rosenthal et al. 2011; Sapolsky 2004), as does parts of the physiological process of nicotine dependence and some psychiatric disorders, for example depression (Quattrocki et al. 2000). Smoking may then be a method for coping with stress and common psychiatric disorders.

The relationship between smoking and stress is complex and difficult to disentangle. Smoking initiation, maintenance and cessation, as well as exposure to stressors and coping with stress, are processes rather than discrete events. Notwithstanding, a review by Kassel et al. (2003) reports that empirical studies have consistently found a link between stress and all stages of smoking. The release of dopamine, which is stimulated by nicotine, alleviates stress making smoking a viable option to cope with stress regardless of social strata. Individuals in lower social strata are, however, more likely to experience stress (Brunner 1997; Thoits 2006), for example through exposure to negative life events such as unemployment (Whelan 1994), financial strain (Shaw et al. 2014) and divorce (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2006), and experience more severe consequences (Pearlin 1989; Thoits 2006). Coping with stress requires access to material and non-material resources and smoking may be a more viable coping strategy for individuals with fewer resources, as cigarettes are comparatively cheap and accessible.

Depression and nicotine dependence involve overlapping physiological processes that influence, among other things, the release of dopamine and serotonin (Quattrocki et al. 2000), and it is possible that cigarettes are sometimes used as self-medication against depression and other psychiatric disorders. This may be an effective strategy. Cotinine, a substance that is released into the body when nicotine is metabolized, is both a biomarker used to indicate exposure to nicotine and an antidepressant (Benowitz et al. 2009; Echeverria Moran 2012; Grizzell and Echeverria 2015). Smoking is more common among individuals with a psychiatric disorder including comparatively common disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Covey et al. 1998; Fluharty et al. 2016). Several studies that use Mendelian randomization have found that a genetic predisposition to smoking does not predict depression. This indicates that there is no causal effect of smoking on depression (Taylor et al. 2014). A persistent link between low social position, depression and mental health problems has also been reported (Lorant et al. 2003), although it remains unclear whether the relationship between depression and low social position is causal (Reiss 2013). The use of smoking as a form of self-medication for both stress and common psychiatric disorders may contribute to the emergence of a social gradient in smoking.

The social gradient in smoking cessation

While a majority of smokers intend to quit smoking (Siahpush et al. 2009), most singular quit attempts are unsuccessful (West et al. 2001). Despite most successful quit attempts being unaided, the probability of remaining smoke-free after an unaided quit attempt has been consistently found to be around 3–5% (Cohen et al. 1989; Hughes et al. 2004). When quitting smoking, the individual experience nicotine withdrawal symptoms. The first symptom is a desire to smoke which intensifies over time (DiFranza et al. 2011). Eventually, the individual experiences discomfort in terms of elevated stress, anxiety, irritability and sleeping difficulties (Benowitz 2010; Dani and Heinemann 1996). These symptoms motivate a relapse. Most of the withdrawal symptoms peak sometime between the first day and the first two weeks after cessation (Piasecki et al. 2002; Ward et al. 1997), which is also when the majority of relapses occur (Hughes et al. 2004). After the first few weeks, relapses are more likely to happen as the result social or situational cues that activate nicotine cravings (Rosenthal et al. 2011). When a former smoker is in a situation in which they would previously have smoked a cigarette, associative or affective processes activate physiological processes resulting in the craving of a cigarette (Piasecki et al. 2002).

Studies on smoking cessation generally find that smokers in higher social strata are, on average, more likely to quit smoking (Hiscock et al. 2012; Kotz and West 2009; Reid et al. 2010), and are more successful in abstaining for longer periods of time (Hiscock et al. 2010; Marti 2010). Nicotine dependence constitutes a substantial barrier to smoking cessation (Ussher et al. 2016) and it is possible that smokers in lower social strata have a greater difficulty in quitting because of stronger nicotine dependence. Evidence from surveys as well as studies measuring biological indicators of nicotine dependence have suggested that smokers in lower social strata are more heavily dependent on nicotine (Hiscock et al. 2012; Siahpush et al. 2006). This finding is perhaps unsurprising since a higher smoking prevalence may indicate more long-time smokers (these are less likely to have quit at the point of measurement) and long-term smokers are more likely to develop nicotine dependence (Donny and Dierker 2007). A higher prevalence of smoking and stronger nicotine dependence is then, at least in part, closely related phenomena observed at the individual and population level, respectively.

Both social support and material resources help individuals to quit smoking. Social and situational cues are likely more prevalent for former smokers in lower social strata, since there are on average more current smokers in their networks. Financial strain has also been found to be associated with lower probability to successful cessation (Layte and Whelan 2008; Siahpush et al. 2009), as has major depression (Glassman et al. 1990). If smoking is used as a method to cope with stress or a psychiatric disorder, these conditions remain during the cessation attempt and make it more difficult to quit smoking. This could further contribute to the social gradient in smoking cessation since both stress (Brunner 1997) and psychiatric disorders (Lorant et al. 2003) are more common in lower social strata.

Concluding remarks

In this article, I have argued that individual smoking behaviour, physical nicotine dependence and social norms surrounding smoking are related through a set of reflexive processes. Repeated nicotine exposure leads to physical dependence that in turn motivates the individual to smoke and the social norms surrounding smoking in the social network are continuously reproduced and modified as individuals converge or diverge from them. The reflexive relationships between individual smoking behaviour, nicotine dependence and social norms highlight the importance of the physical body in any account of individual agency. Individual agency is not only conditional on the external physical and social environment, but also the physiological properties and processes of the body. Social norms are produced and reproduced through individual agency. Similarly, the physiological make-up of the body is continuously shaped by individual agency. This can in turn both enable and restrict the scope of prospective agency. From this perspective, social structures and physiological processes are simultaneous and integrated in an ongoing process of reproduction and change.

The aim of this article was to develop a framework for understanding why a social gradient in smoking tends to emerge and persist in later stages of the cigarette epidemic, integrating perspectives from both social sciences and medicine. I identified that the combination of an unequal distribution of material and non-material resources, social homophily and the addictive and antidepressant properties of nicotine may contribute to higher smoking rates in lower social strata relative to higher social strata. These factors are not context-specific and may promote the emergence and persistence of social gradients in smoking regardless of culture, level of economic development and tobacco control policies.

Smoking is the subject of extensive research in several scientific disciplines but studies tend to focus on different factors depending on the disciplinary focus. Highly specialized studies provide detailed and crucial knowledge on the specifics of nicotine dependence, individual behaviour or social norms but if these aspects are not considered together, the complexity of smoking may be underestimated. Furthermore, if tobacco control policies are designed based on a simplified understanding of smoking, for example considering smoking as either a medical problem or a moral one, policies may be less effective or have unintended consequences. Future studies should adapt a transdisciplinary approach and consider the combination of physiological and social processes surrounding smoking and other behavioural risk factors, for example excessive alcohol use and obesity. Doing so will promote a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the social patterning of health behaviours.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub.

Bell, K. 2011. Legislating abjection? Secondhand smoke, tobacco control policy and the public’s health, Critical Public Health 21 (1): 49–62.

Bell, K., and S. Dennis. 2013. Towards a critical anthropology of smoking: Exploring the consequences of tobacco control. Contemporary Drug Problems 40: 3–19.

Benowitz, N.L. 2010. Nicotine addiction. New England Journal of Medicine 362 (24): 2295–2303.

Benowitz, N.L., J. Hukkanen, and P. Jacob. 2009. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers Nicotine Psychopharmacology, 29–60. Berlin: Springer.

Berridge, V. 1998. Science and policy: The case of postwar British smoking policy. In Ashes to ashes, ed. S. Lock, L. Reynolds, and E.M. Tansey, 143–163. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Bosdriesz, J.R., M.C. Willemsen, K. Stronks, and A.E. Kunst. 2015. Socioeconomic inequalities in smoking cessation in 11 European countries from 1987 to 2012. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 69 (9): 886–892.

Brandt, A.M. 1998. Blow some my way: Passive smoking, risk and American culture. In Ashes to ashes, ed. S. Lock, L. Reynolds, and E.M. Tansey, 164–191. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Brown, T., S. Platt, and A. Amos. 2014. Equity impact of European individual-level smoking cessation interventions to reduce smoking in adults: A systematic review. The European Journal of Public Health 24 (4): 551–556.

Brunner, E. 1997. Socioeconomic determinants of health: Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ 314 (7092): 1472.

Cockerham, W.C. 2005. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 46 (1): 51–67.

Cohen, S., E. Lichtenstein, J.O. Prochaska, J.S. Rossi, E.R. Gritz, C.R. Carr, C.T. Orleans, V.J. Schoenbach, L. Biener, and D. Abrams. 1989. Debunking myths about self-quitting: Evidence from 10 prospective studies of persons who attempt to quit smoking by themselves. American Psychologist 44 (11): 1355.

Coleman, J.S. 1994. Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Covey, L.S., A.H. Glassman, and F. Stetner. 1998. Cigarette smoking and major depression. Journal of Addictive Diseases 17 (1): 35–46.

Dani, J.A., and S. Heinemann. 1996. Molecular and cellular aspects of nicotine abuse. Neuron 16 (5): 905–908.

De Graaf, P.M., and M. Kalmijn. 2006. Change and stability in the social determinants of divorce: A comparison of marriage cohorts in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review 22 (5): 561–572.

Delormier, T., K.L. Frohlich, and L. Potvin. 2009. Food and eating as social practice—Understanding eating patterns as social phenomena and implications for public health. Sociology of Health & Illness 31 (2): 215–228.

Dennis, S. 2013. Researching smoking in the new smokefree: Good anthropological reasons for unsettling the public health grip. Health Sociology Review 22 (3): 282–290.

DiFranza, R.J., J.R. Wellman, R. Mermelstein, L. Pbert, D.J. Klein, D.J. Sargent, S.J. Ahluwalia, A.H. Lando, J.D. Ossip, and M.K. Wilson. 2011. The natural history and diagnosis of nicotine addiction. Current Pediatric Reviews 7 (2): 88–96.

DiMaggio, P., and F. Garip. 2011. How network externalities can exacerbate intergroup inequality. American Journal of Sociology 116 (6): 1887–1933.

Doll, R., and A.B. Hill. 1950. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. British Medical Journal 2 (4682): 739.

Donny, E.C., and L.C. Dierker. 2007. The absence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence in moderate-to-heavy daily smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 89 (1): 93–96.

Echeverria Moran, V. 2012. Cotinine: Beyond that expected, more than a biomarker of tobacco consumption. Frontiers in Pharmacology 3: 173.

Evans-Polce, R.J., J.M. Castaldelli-Maia, G. Schomerus, and S.E. Evans-Lacko. 2015. The downside of tobacco control? Smoking and self-stigma: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 145: 26–34.

Factor, R., I. Kawachi, and D.R. Williams. 2011. Understanding high-risk behavior among non-dominant minorities: A social resistance framework. Social Science and Medicine 73 (9): 1292–1301.

Fluharty, M., A.E. Taylor, M. Grabski, and M.R. Munafò. 2016. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 19 (1): 3–13.

GBD 2017 Risk Facor Collaborators. 2018. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 392: 1923–1994.

Giddens, A. 1984. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

Gilman, S.E., D.B. Abrams, and S.L. Buka. 2003. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: Initiation, regular use, and cessation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57 (10): 802–808.

Glassman, A.H., J.E. Helzer, L.S. Covey, L.B. Cottler, F. Stetner, J.E. Tipp, and J. Johnson. 1990. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA 264 (12): 1546–1549.

Goldthorpe, J.H. 2000. On sociology: Numbers, narratives, and the integration of research and theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Goldthorpe, J.H. 2016. Sociology as a population science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graham, H. 2012. Smoking, stigma and social class. Journal of Social Policy 41: 83.

Grizzell, J.A., and V. Echeverria. 2015. New insights into the mechanisms of action of cotinine and its distinctive effects from nicotine. Neurochemical Research 40 (10): 2032–2046.

Heatherton, T.F., L.T. Kozlowski, R.C. Frecker, and K.-O. Fagerström. 1991. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction 86 (9): 1119–1127.

Hill, S., A. Amos, D. Clifford, and S. Platt. 2014. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: Review of the evidence. Tobacco Control 23 (e2): e89–e97.

Hiscock, R., L. Bauld, A. Amos, J.A. Fidler, and M. Munafo. 2012. Socioeconomic status and smoking: A review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1248 (1): 107–123.

Hiscock, R., K. Judge, and L. Bauld. 2010. Social inequalities in quitting smoking: What factors mediate the relationship between socioeconomic position and smoking cessation? Journal of Public Health 33 (1): 39–47.

Hughes, J.R., and D. Hatsukami. 1986. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry 43 (3): 289–294.

Hughes, J.R., J. Keely, and S. Naud. 2004. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 99 (1): 29–38.

Joossens, L., and M. Raw. 2006. The Tobacco Control Scale: A new scale to measure country activity. Tobacco Control 15 (3): 247–253.

Kassel, J.D., L.R. Stroud, and C.A. Paronis. 2003. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin 129 (2): 270.

Kotz, D., and R. West. 2009. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: It’s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tobacco Control 18 (1): 43–46.

Krieger, N. 2008. Ladders, pyramids and champagne: The iconography of health inequities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 62 (12): 1098–1104.

Krieger, N. 2011. Epidemiology and the people’s health: Theory and context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Layte, R., and C.T. Whelan. 2008. Explaining social class inequalities in smoking: The role of education, self-efficacy, and deprivation. European Sociological Review 25 (4): 399–410.

Legleye, S., M. Khlat, F. Beck, and P. Peretti-Watel. 2011. Widening inequalities in smoking initiation and cessation patterns: A cohort and gender analysis in France. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 117 (2–3): 233–241.

Lock, S., L. Reynolds, and E.M. Tansey. 1998. Ashes to ashes: The history of smoking and health. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Lopez, A.D., N.E. Collishaw, and T. Piha. 1994. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tobacco Control 3 (3): 242.

Lorant, V., D. Deliège, W. Eaton, A. Robert, P. Philippot, and M. Ansseau. 2003. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 157 (2): 98–112.

Lorant, V., V.S. Rojas, P.-O. Robert, J.M. Kinnunen, M.A. Kuipers, I. Moor, G. Roscillo, J. Alves, A. Rimpelä, and B. Federico. 2017. Social network and inequalities in smoking amongst school-aged adolescents in six European countries. International Journal of Public Health 62 (1): 53–62.

Main, C., S. Thomas, D. Ogilvie, L. Stirk, M. Petticrew, M. Whitehead, and A. Sowden. 2008. Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking: Placing an equity lens on existing systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 8 (1): 178.

Marti, J. 2010. Successful smoking cessation and duration of abstinence—An analysis of socioeconomic determinants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7 (7): 2789–2799.

McPherson, M., L. Smith-Lovin, and J.M. Cook. 2001. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 415–444.

Merton, R.K. 1987. Three fragments from a sociologist’s notebooks: Establishing the phenomenon, specified ignorance, and strategic research materials. Annual Review of Sociology 13 (1): 1–29.

Miething, A. 2014. Others’ income, one’s own fate: How income inequality, relative docial position and social comparisons contribute to disparities in health. Stockholm: Department of Sociology, Stockholm University.

Miething, A., M. Rostila, C. Edling, and J. Rydgren. 2016. The influence of social network characteristics on peer clustering in smoking: A two-wave panel study of 19-and 23-year-old swedes. PLoS ONE 11 (10): e0164611.

Muhammad-Kah, R.S., A.D. Hayden, Q. Liang, K. Frost-Pineda, and M. Sarkar. 2011. The relationship between nicotine dependence scores and biomarkers of exposure in adult cigarette smokers. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 60 (1): 79–83.

Mukherjee, S. 2010. The emperor of all maladies: A biography of cancer. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Pampel, F.C., P.M. Krueger, and J.T. Denney. 2010. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 349–370.

Pearlin, L.I. 1989. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30: 241–256.

Petrovic, D., C. de Mestral, M. Bochud, M. Bartley, M. Kivimäki, P. Vineis, J. Mackenbach, and S. Stringhini. 2018. The contribution of health behaviors to socioeconomic inequalities in health: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine 113: 15–31.

Piasecki, T.M., M.C. Fiore, D.E. McCarthy, and T.B. Baker. 2002. Have we lost our way? The need for dynamic formulations of smoking relapse proneness. Addiction 97 (9): 1093–1108.

Quattrocki, E., A. Baird, and D. Yurgelun-Todd. 2000. Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8 (3): 99–110.

Reid, J.L., D. Hammond, C. Boudreau, G.T. Fong, M. Siahpush, and I. Collaboration. 2010. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 12 (suppl 1): S20–S33.

Reiss, F. 2013. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine 90: 24–31.

Rooke, C. 2013. Harm reduction and the medicalisation of tobacco use. Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (3): 361–376.

Rosenthal, D.G., M. Weitzman, and N.L. Benowitz. 2011. Nicotine addiction: Mechanisms and consequences. International Journal of Mental Health 40 (1): 22–38.

Sapolsky, R.M. 2004. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping: Holt paperbacks.

Seo, D.C., and Y. Huang. 2012. Systematic review of social network analysis in adolescent cigarette smoking behavior. Journal of School Health 82 (1): 21–27.

Sewell Jr., W.H. 1992. A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. American Journal of Sociology 98 (1): 1–29.

Shaw, R.J., M. Benzeval, and F. Popham. 2014. To what extent do financial strain and labour force status explain social class inequalities in self-rated health? Analysis of 20 countries in the European Social survey. PLoS ONE 9 (10): e110362.

Siahpush, M., A. McNeill, R. Borland, and G. Fong. 2006. Socioeconomic variations in nicotine dependence, self-efficacy, and intention to quit across four countries: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control 15 (suppl 3): iii71–iii75.

Siahpush, M., H.H. Yong, R. Borland, J.L. Reid, and D. Hammond. 2009. Smokers with financial stress are more likely to want to quit but less likely to try or succeed: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction 104 (8): 1382–1390.

Slade, J. 1989. The tobacco epidemic: Lessons from history. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 21 (3): 281–291.

So, V.H., C. Best, D. Currie, and S. Haw. 2019. Association between tobacco control policies and current smoking across different occupational groups in the EU between 2009 and 2017. Journal of Epidemiol Community Health 73 (8): 759–767.

Stuber, J., S. Galea, and B.G. Link. 2008. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Social Science and Medicine 67 (3): 420–430.

Studlar, D.T. 2008. US tobacco control: Public health, political economy, or morality policy? Review of Policy Research 25 (5): 393–410.

Taylor, A.E., M.E. Fluharty, J.H. Bjørngaard, M.E. Gabrielsen, F. Skorpen, R.E. Marioni, A. Campbell, J. Engmann, S.S. Mirza, and A. Loukola. 2014. Investigating the possible causal association of smoking with depression and anxiety using Mendelian randomisation meta-analysis: The CARTA consortium. British Medical Journal Open 4 (10): 1–13.

Thoits, P.A. 2006. Personal agency in the stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47 (4): 309–323.

Thun, M., R. Peto, J. Boreham, and A.D. Lopez. 2012. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tobacco Control 21 (2): 96–101.

Tombor, I., L. Shahab, J. Brown, and R. West. 2013. Positive smoker identity as a barrier to quitting smoking: Findings from a national survey of smokers in England. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 133 (2): 740–745.

Tombor, I., L. Shahab, A. Herbec, J. Neale, S. Michie, and R. West. 2015. Smoker identity and its potential role in young adults’ smoking behavior: A meta-ethnography. Health Psychology 34 (10): 992.

Ussher, M., G. Kakar, P. Hajek, and R. West. 2016. Dependence and motivation to stop smoking as predictors of success of a quit attempt among smokers seeking help to quit. Addictive Behaviors 53: 175–180.

Wang, H., and X. Sun. 2005. Desensitized nicotinic receptors in brain. Brain Research Reviews 48 (3): 420–437.

Ward, K.D., R.C. Klesges, and M.T. Halpern. 1997. Predictors of smoking cessation and state-of-the-art smoking interventions. Journal of Social Issues 53 (1): 129–145.

Wellman, R.J., E.N. Dugas, H. Dutczak, E.K. O’Loughlin, G.D. Datta, B. Lauzon, and J. O’Loughlin. 2016. Predictors of the onset of cigarette smoking: A systematic review of longitudinal population-based studies in youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51 (5): 767–778.

West, R., A. McEwen, K. Bolling, and L. Owen. 2001. Smoking cessation and smoking patterns in the general population: A 1-year follow-up. Addiction 96 (6): 891–902.

Whelan, C.T. 1994. Social class, unemployment, and psychological distress. European Sociological Review 10 (1): 49–61.

World Health Organization. 1992. ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to Olle Lundberg for his critique, encouragement and insightful comments.

Funding

This research was supported by the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (Grant MMW 2014.0016). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Östergren, O. The social gradient in smoking: individual behaviour, norms and nicotine dependence in the later stages of the cigarette epidemic. Soc Theory Health 20, 276–290 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-021-00159-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-021-00159-z