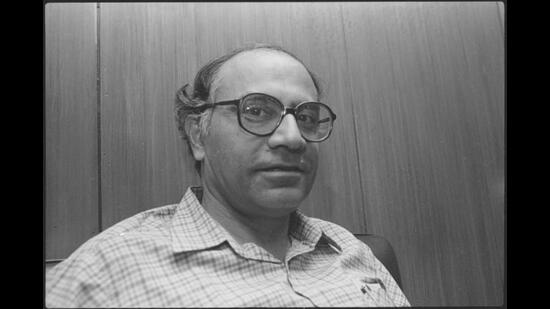

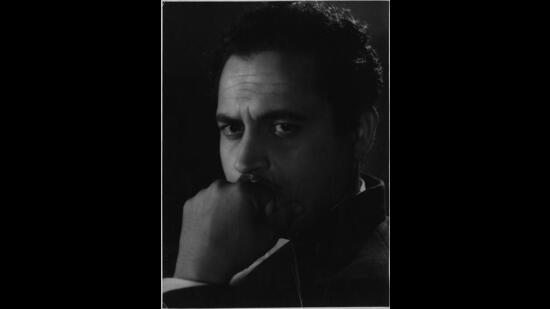

Interview: Rajat Kapoor: ‘Everyone ends up chasing stars’

The director, writer and actor talks about making offbeat films, writing for theatre, being influenced by Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul, the tragedy of NFDC, and his belief that cinema is supposed to illuminate

What do you like reading?

Fiction, when I can. But now it’s becoming less and less, I must admit. Because these days, I am reading a lot of scripts and that takes up a lot of my time, my reading time. But I have read a lot for about 45 years of my life. And I have read various things, everything. There are, of course, a few favourites. I started with Hindi literature when I was in Delhi in my teens. That’s when I read a lot of Hindi literature. People like Rajendra Yadav and Manu Bhandari and Colonel Ranjit and those pulp fiction kind of stories as well as the classics. Then, of course, world literature. If I were asked to pick one person of all I have read, I rate Dostoevsky very highly. I have not read anybody else who writes with that kind of delirious madness. It looks like he’s possessed when he’s writing. Sentences go on; everything is pitched high. It’s quite feverish. It’s like a feverish delirium and you can’t put the book down. Maybe I should make a film like that, you know, when all characters are acting that high a pitch. That might be fun, don’t you think?

Exactly! How and when did you start writing?

I started writing when I went to FTII. Though, I must say, there was not much importance given to writing in FTII in those days. The direction course was good but the writing one wasn’t. Even the people there didn’t take writing seriously. Everyone was like “Oh, we’re filmmakers!” so a script was looked down upon in a very strange way. People believed that it’s a medium of images and they wanted to create abstract images on film. There were two reasons for writing to be treated this way. One was the belief that we are all imager-makers and the second one was everyone wanted to run away from the hard work that is writing. It was more an escape route than anything else. Who wants to write? Let’s just go and shoot something. That was the attitude.

But then you come out and then you realise that you have to write; because you have to present your script to someone. That is the first step of making a film. So I started writing. When I started assisting Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul, I started to write by the end of my apprenticeship. I remember very well that the first script I wrote was an adaptation of a story by Jorge Luis Borges, the great South American writer. My script was based on his story The Improbable Imposter Tom Castro. Nothing really happened to the script, the film never got made. But I guess, years later, somewhere it came back to me as part of my film Mithya where somebody is impersonating someone. And then 1993-94, I wrote Private Detective, which luckily got made. And I have been writing ever since. I have been writing since the mid-1990s. Every few years, I spent almost two-three months writing. And I write and I throw the draft sometimes. Sometimes, I go back to it after two years. Sometimes, some drafts get discarded because they don’t work out. But I try to give every idea a fair chance. At least two-three drafts. And if it still doesn’t work out, I move on to the next one.

Do you think that enough of importance is given to writing in the Hindi film industry?

We all know the general answer to this question. What has been changing now is that people have started asking for bound scripts unlike before. But what is in that bound script? Good stuff? Rarely. But at least people are making an effort to write and get themselves registered with the writers association. But I don’t think that improved the quality of writing or scripts. You know, my teacher, Mani Kaul had an interesting thing to say about it. He said that we are oral people; we are people of the ear. We like to hear things to understand them. That’s why music is such a big thing in our part of the world. Anyone can listen to a song and say that this, for instance, is Raag Todi and this is the sur and this is the taal that goes with it. That’s why we have so many songs in our films. The story just meanders somewhere near all this without much attention or importance. The idea of writing a script itself was not developed.

The story was just to keep the songs moving or to keep the emotions moving. It was just a ploy. Now, with the younger generation of filmmakers, who are a little influenced by western filmmakers or mainly Hollywood filmmakers, the story has assumed some importance. But you know, I don’t think we are pushing ourselves at all. I don’t know any writers of films that are pushing themselves at all, unfortunately. I am sure poets or novelists or other writers are doing that. But film writers are not. In that, I think, nothing really has changed. And I know that it works both ways. Because if you write a good script, you never know how long it will take to get made or if it will ever get made at all. So then why bother? Might as well say, I am doing Dabangg 8 and be happy with it. But I am not talking about the newcomers here. Their struggle is valid and is another story. But what about the established people? Do you think they’re pushing themselves enough? I think it’s a lack of ambition to even look at ourselves as an artist or to look at cinema as a medium of art.

We look at cinema as a medium to make money, a trade, a business. Who made how much at the box office; who is making money; that’s all we talk about. Even if people go for a film preview, nobody talks about how they liked it. They say if it will work or not. I mean, what do you care if it will work or not? Why don’t you say how you liked it? Whereas cinema as a medium is supposed to do something else. It’s supposed to light up things. It’s supposed to illuminate you. It’s supposed to make you aware of things that you either weren’t before or if you were, you weren’t able to find an expression for them. That is what cinema and art are supposed to do in my view.

Did you always want to be a writer? How did all this start?

I always wanted to be a filmmaker. My father was a great film buff. I watched a lot of films as a child. I remember very well, in 1974, when I was 13 years old, my father used to take us to watch all the award-winning films that were shown in Delhi at an event. And I remember, at 13, my father took me to watch Mani Kaul’s Duvidha. Maybe something stirred within me there. Then around 16, I watched some films by Werner Herzog and then later Ingmar Bergman and Jean-Luc Godard. I was lucky that I got to watch this kind of cinema at these film societies in Delhi. I got to FTII when I was 25, which was quite late; most people joined it by 20-21. But I took some time to convince my parents. By the time I applied to FTII and got through, I was certain that I wanted to be a filmmaker.

You have always written peculiar stories and screenplays especially in the context of the Hindi film industry. Has that been a conscious choice?

I don’t think it’s a conscious choice. This is just who I am. And I think the biggest struggle for any artist in this world is to find who they are. And to find their expression. The film I made in 1995, Private Detective, was so influenced by Kumar Shahani. Yes, it was a thriller that has a murder and everybody is a suspect and all of that, but in the making, it was all influenced by Kumar Shahani. In the writing, it was me. It took me about 10 years to become my own man. In 1996-97, I made a short film called Hypnothesis about clowns. I think with that I started to find my own voice.

Tell me about the journey of making Aankhon Dekhi.

Many scripts I have had are ideas that have evolved over time. For Aankhon Dekhi, I had an idea for a long time about a man who decides that what he has experienced is his only truth. This stuck with me but I didn’t know what to do with it; because an idea is not a film. Like an idea is not a poem. A poem is made with words. The words have to resonate, not the idea.

Then, many years later, I thought, “Joint family”. Boom! And there I had a way ahead. The dream of babuji flying is a dream that I have had. It was a recurring dream for me. One of my most joyous dreams. And then after I made the film, I never had that dream again. Aakhon Dekhi was comparatively easy to make because Manish Mundra, whom I met on Twitter, produced it albeit that was after the studios had rejected it. All my films have had a long wait and their own journeys. RK/Rkay was very difficult to make in comparison. I had to put my own money, a part of it was crowdfunded. When I was writing Aakhon Dekhi, I was already thinking Sanjay Mishra. Because I had just done Phas Gaye Re Obama with him as an actor and I thought he fit my character very well.

How did Mixed Doubles happen and what about your constant collaboration with Ranvir Shorey?

That was my first film with Ranvir. I auditioned him. He was great. The film had an interesting journey. The thing is I had made Raghu Romeo, which made it to the Locarno film festival. And we were on a big high. We thought it’s an international breakthrough. The film was shown at an open-air venue and trust me, there were 9000 people watching it! 9000 people clapping for that film. It was unbelievable. I thought I had a hit on our hands. But then it released here and it bombed and I went into depression. But what happened is that at Locarno film festival, there was this gentleman called Sunil Doshi, whom I became friends with. He told me he has 60 lakh rupees and if I could make a film in that much. I said yes. He asked if I had a script. I shared two ideas with him, one of which was Mixed Doubles. He said yes and we jumped into it. I didn’t want to lose that opportunity. I wrote and made the film in two months. Since you asked me how the idea came to me, in 2004, when I went to Locarno, I was really depressed and my ticket was bought by someone else. So from Locarno, I went to Geneva and my flight back was the next morning. I didn’t have the money to book a hotel so I thought I’d spend the night at the airport itself. But they said the airport was shut! I was like, how can an airport be shut at night? But then, anyway, I went back to the train station. And I ordered a coffee to stay up all night. In that café, I wrote on a tissue paper: Mixed Doubles. And then the story occurred to me.

How do you go about writing theatre?

Let me tell you my process of writing theatre. It’s very interesting. I call a few friends whom I want to work with. And then we decide what we want to do. For instance, Hamlet – The Clown Prince. The first day we meet, we read the first scene of Hamlet. We destroy the scene. Finally, what we are left with has got nothing to do with the original scene. But we build like that and build like that. We don’t know where we are going. Yes, there is a chance of falling completely flat on your face in a process like that.

But that’s the risk that you run and that’s where the fun is. Then, in the case of King Lear, we go into themes of the original play, not the text. Father and daughter and loss of youth. For days, we talk about loss of youth. We start getting back to our own stories related to that theme and develop something. And that’s why we call it Nothing Like Lear. Because it’s nothing like the original play. Though, at the same time, it’s every bit the original play. The process is very exciting and very scary. There is no safety net. By now, I have done four Shakespeare plays and in all, followed the same process. I think Shakespeare is unbeatable. It’s not just his craft or his words. It’s the depth. You can’t go beyond Hamlet. And it is as modern as it was 500 years ago. Why has no one written anything better in five centuries? Shakespeare is a colossus.

Does being an actor help the writer in you?

Not really. I’d say, all it does is that it helps me empathise a little more with my actors. I understand where they are coming from.

How do you see the industry change in the last 30-odd years?

Things haven’t changed. If we speak in a larger way, nothing has changed. And nothing will change for the next 30 years either. I say that because we have been making the same mediocre stuff that we were making 30 years ago. There are changes that happened in tiny spurts. For instance, when the multiplexes came in, we thought our kind of cinema will now be made. It worked for a couple of years and then the multiplexes started getting bombarded with the same old kind of stuff.

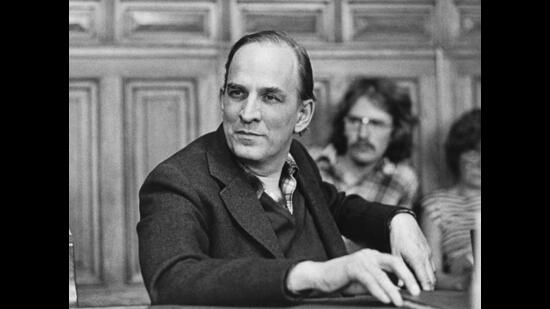

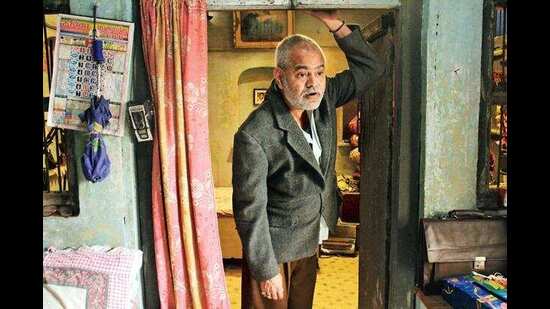

When the OTT platforms came in, we again thought, now indie cinema will get a boost. Nothing happened! They all fall in the same traps of the system. They all want to play to the system. Everyone ends up chasing superstars and stars. That’s the only thing they know in this industry. And it’s not just here but in Hollywood as well. It’s like gambling and putting money on the horse that’s likely to win the race. It’s not about telling stories or making films for anyone. I would say modern Hollywood is as bad. One unfortunate thing that has happened is that in the 1980s, there was NFDC, which kind of backed out by the early 1990s. That was a terrible tragedy. Because filmmakers like Saeed Mirza, Kumar Shahani, Mani Kaul, Shyam Bengal were denied opportunities to make any more films after that. While we think that we have taken leaps ahead, actually we have regressed. Because there was state support of cinema back then, which doesn’t exist anymore. The whole new wave of the 1970s and the 80s started because of NFDC.

Even in the western world, in those days, great cinema was state funded to some extent. In France, in Germany, in Austria. The great Germans like Herzog and Fassbinder were helped by the state. Why would the so-called market be interested in a Kumar Shahani film? It’s a matter of shame, national shame, that Kumar has not made a film in the last 15 years! He lives, he is 82 years old. What are we celebrating, man? For 20 years, I have been hearing that things have changed. We say now it has all been democratised. We keep hearing that cinema is getting better, the audience is getting better. Show me where? I can’t think of one film. Well, I remember Court. I’d say that was a fantastic film. Gangs of Wasseypur is one of my favourites. But that’s it. I have to stop after that. Show me what else? Where is the progress? Some people say that it’s because of the audience that we make the films we do. But you have to make films for yourself, not for an audience. If you do the latter, you are in the business of films. Not in the art of films. But if you are interested in the medium, how can you make anything lesser than you? However, I must accept one thing here. That any kind of art comes much later in your evolution. I mean, if 50% of the population in the city lives in slums and so many in this country are below the poverty line, how can you talk art to them? We don’t have basic sanitation to give them, no basic food or education. How can we expect them to come and watch what we perceive as art? They have other concerns. That’s why I am saying that nothing is going to change in this country for the next 30 years. Art is a far-fetched concept for most people here where their basic needs are not met. Art is spiritual but before that, what about the corporeal?

Where do you stand on the advent of OTT?

I think I am comfortable with my 90 minutes. Just like every short story writer needn’t be a great novelist and vice versa, I think every film writer cannot be a show or a long form writer. I think OTT shows are a different medium. And at least, so far I have never had an idea that needs more than a film. One good thing that OTT has done though is that it has made some rare films available. Aaknhon Dekhi slipped out of theatres when it released but it got a new life on OTT. For that, I am really thankful to the OTT platforms.

What are you cinematic influences?

The list is huge. The constant one and two have been Charlie Chaplin and Federico Fellini. I think Chaplin is the greatest ever filmmaker of all time. He is incredible. And Fellini has had a lasting influence on me. Then, after these two, there is a long list. Billy Wilder, Godard. Then there is a French filmmaker called Eric Rohmer I like very much. Then Ritwik Ghatak, Guru Dutt. I like Guru Dutt very much.

Then there are films I don’t talk about much. Because I am very away from mainstream cinema. But as a child, the film that impressed me a lot was Deewar. I must have been 13-14 when I saw it. I think it has affected my psyche. In Aankhon Dekhi, there might be a bit of Balraj Sahni’s Do Raste. These are some of the mainstream films that have impacted me earlier in my life in a deep, deep way. I met Javed sahab recently on a flight and I walked up to him and told him that Deewar is one of my favourite films. I told him I still remember that scene between Bachchan and Parveen Babi, after having made love, lying on the bed, smoking cigarettes. When was the last time you saw that on screen in a Hindi film? It’s incredible. That has just stayed with me. The idea of sin, a taboo.

What’s your creative purpose?

Philosophically speaking, I think celebrating life and joy. I don’t relate to morbidity or self-destruction at all, which filmmakers like Michael Haneke might come from. I am not against making people uncomfortable. That is, of course, a role of art. But a morbid view of the world, the gloom that a person like Kieslowski might bring in is something I don’t relate to. I mean, Haneke and Kieslowski are great filmmakers but I am telling you where I come from. I belong more to the Fellini world; the world of joy.

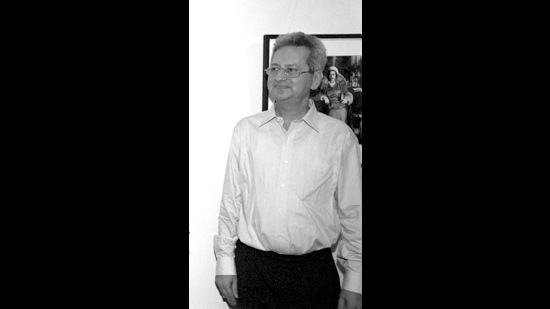

Mihir Chitre is the author of two books of poetry, ‘School of Age’ and ‘Hyphenated’. He is the brain behind the advertising campaigns ‘#LaughAtDeath’ and ‘#HarBhashaEqual’ and has made the short film ‘Hello Brick Road’.

Catch every big hit, every wicket with Crick-it, a one stop destination for Live Scores, Match Stats, Quizzes, Polls & much moreExplore now!

See more

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription