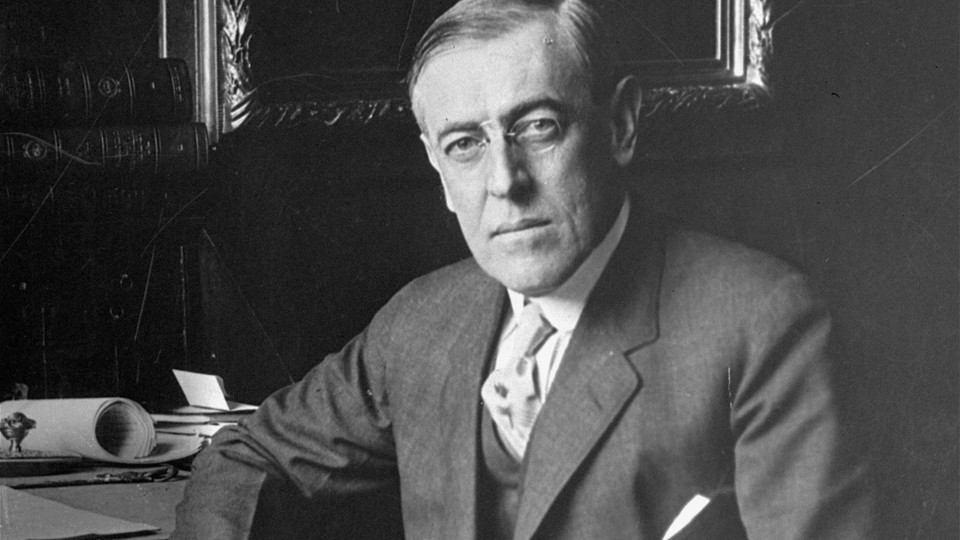

The Racist Legacy of Woodrow Wilson

Students at Princeton University are protesting the ways it honors the former president, who once threw a civil-rights leader out of the White House.

The Black Justice League, in protests on Princeton University’s campus, has drawn wider attention to an inconvenient truth about the university’s ultimate star: Woodrow Wilson. The Virginia native was racist, a trait largely overshadowed by his works as Princeton’s president, as New Jersey’s governor, and, most notably, as the 28th president of the United States.

As president, Wilson oversaw unprecedented segregation in federal offices. It’s a shameful side to his legacy that came to a head one fall afternoon in 1914 when he threw the civil-rights leader William Monroe Trotter out of the Oval Office.

Trotter led a delegation of blacks to meet with the president on November 12, 1914, to discuss the surge of segregation in the country. Trotter, today largely forgotten, was a nationally prominent civil-rights leader and newspaper editor. In the early 1900s, he was often mentioned in the same breath as W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. But unlike Washington, Trotter, an 1895 graduate of Harvard, believed in direct protest actions. In fact, Trotter founded his Boston newspaper, The Guardian, as a vehicle to challenge Washington’s more conciliatory approach to civil rights.

Before Trotter’s confrontation with Wilson in the Oval Office, he was a political supporter of Wilson’s. He had pledged black support for Wilson’s presidential run when the two met face-to-face in July 1912 at the State House in Trenton, New Jersey. Even though then-Governor Wilson offered only vague promises about seeking fairness for all Americans, Trotter apparently came away smitten. “The governor had us draw our chairs right up around him, and shook hands with great cordiality,’’ he wrote a friend later. “When we left he gave me a long handclasp, and used such a pleased tone that I was walking on air.” Trotter viewed Wilson as the lesser of other political evils.

The civil-rights leader was soon having second thoughts. In the fall of 1913, he and other civil-rights leaders, including Ida B. Wells, met with Wilson to express dismay over Jim Crow. Trotter’s wife, Deenie, had even drawn a chart showing which federal offices had begun separating workers by race. Wilson sent them off with vague assurances.

In the next year, segregation did not improve; it worsened. By this time, numerous instances of workplace separation became well publicized. Among them, separate toilets in the U.S. Treasury and the Interior Department, a practice that Wilson’s Treasury secretary, William G. McAdoo, defended: “I am not going to argue the justification of the separate toilets orders, beyond saying that it is difficult to disregard certain feelings and sentiments of white people in a matter of this sort.”

For blacks—who ever since Lincoln’s War had expected some measure of equity from the federal government—the sense of a betrayal ran deep.

Trotter sought a follow-up meeting with the president. “Last year he told the delegation he would seek a solution,’’ he wrote a supporter in the fall of 1914. “Having waited 11 months, we are entitled to an audience to learn what it is. Not only for the sake of his administration but as a matter of common justice.” Of course, the president’s plate was full.

Wilson might have bumbled, and worse, on civil rights, but he was overseeing implementation of a “New Freedom” in the nation’s economy—his campaign promise to restore competition and fair-labor practices, and to enable small businesses crushed by industrial titans to thrive once again. In September 1914, for example, he had created the Federal Trade Commission to protect consumers against price-fixing and other anticompetitive business practices, and shortly after signed into law the Clayton Antitrust Act. He continued monitoring the so-called European War, resisting pressure to enter but moving to strengthen the nation’s armed forces. In addition to attending to the state’s affairs, Wilson was in mourning: His wife, Ellen, had died on August 6 from liver disease. On November 6, one of his advisers noted in his diary that the president had told him “he was broken in spirit by Mrs. Wilson’s death.”

Eventually, Wilson agreed to meet a second time with Trotter, and on November 12 the persistent editor and a contingent of Trotterites entered the Oval Office for their long-sought, long-awaited follow-up meeting. Trotter came prepared with a statement and launched the meeting by reading it.

Trotter began with a reference to their 1913 meeting and to the petition he had presented, containing 20,000 signatures “from thirty-eight states protesting against the segregation of employees of the national government.” He listed the on-the-job race separation that had gone unchecked since—at eating tables, dressing rooms, restrooms, lockers, and “especially public toilets in government buildings.” He then charged that the color line was drawn in the Treasury Department, in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Navy Department, the Interior Department, the Marine Hospital, the War Department, and in the Sewing and Printing Divisions of the Government Printing Office. Trotter also noted the political support he and other civil-rights activists had provided to Wilson. “Only two years ago you were heralded as perhaps the second Lincoln, and now the Afro-American leaders who supported you are hounded as false leaders and traitors to their race,” he said. And then he reminded the president of his pledge to assist “colored fellow citizens” in “advancing the interest of their race in the United States,” and ended by posing a question that contained a jab at Wilson’s much-ballyhooed economic-reform program. “Have you a ‘New Freedom’ for white Americans and a new slavery for your Afro-American fellow citizens? God forbid!”

The meeting quickly turned sour. The president told Trotter what he previously admitted in private—that he viewed segregation in his federal agencies as a benefit to blacks. Wilson said that his cabinet officers “were seeking, not to put the Negro employees at a disadvantage but ... to make arrangements which would prevent any kind of friction between the white employees and the Negro employees.” Trotter found the claim astonishing, and immediately disagreed, calling Jim Crow in federal offices humiliating and degrading to black workers. But Wilson dug in. “My question would be this: If you think that you gentlemen, as an organization, and all other Negro citizens of this country, that you are being humiliated, you will believe it. If you take it as a humiliation, which it is not intended as, and sow the seed of that impression all over the country, why the consequence will be very serious,” he said.

Trotter was incredulous that the president didn’t seem to understand that separating workers based on race “must be a humiliation. It creates in the minds of others that there is something the matter with us—that we are not their equals, that we are not their brothers, that we are so different that we cannot work at a desk beside them, that we cannot eat at a table beside them, that we cannot go into the dressing room where they go, that we cannot use a locker beside them.” There was no letup. In his comments, Trotter had accused the president of lying by saying that race prejudice was the sole motivation for Jim Crow and that to assert otherwise, to claim his administration sought to protect blacks from “friction,” was ridiculous. “We are sorely disappointed that you take the position that the separation itself is not wrong, is not injurious, is not rightly offensive to you,” Trotter said.

Wilson interrupted Trotter: “Your tone, sir, offends me.” To the entire delegation, he said, “I want to say that if this association comes again, it must have another spokesman,” declaring no one had ever come into his office and insulted him as Trotter had. “You have spoiled the whole cause for which you came,” he told The Guardian editor dismissively.

But Trotter would not be dismissed; he was not one to find being surrounded by white people, and the trappings of power either alien or intimidating. He had been the only black in his class at Hyde Park High School outside Boston (where, regardless, he had been elected class president) and, at Harvard, outperformed most white classmates, some of whom had since become governors, congressmen, rich, and famous. Instead, he tried to steer the meeting back on track. “I am pleading for simple justice,” he said. “If my tone has seemed so contentious, why my tone has been misunderstood.” He said they needed to work this out, given that he and other African American leaders had supported Wilson’s presidential run at the polls.

But Wilson was angry, stating that bringing up politics and citing black voting power was a form of blackmail. The meeting, which had lasted nearly an hour, was abruptly over. The delegation was shown the door—essentially thrown out. When the incensed Trotter ran into reporters milling around Tumulty’s office, he began letting off steam. “What the President told us was entirely disappointing.”

The story about the dustup between the president and the Guardian editor went viral. The New York Times’s front-page story was headlined, “President Resents Negro’s Criticism” while the front-page headline in the New York Press read: “Wilson Rebukes Negro Who ‘Talks Up’ to Him.” But the larger point was that his tough-talking landed Trotter back on front pages everywhere.

Wilson realized almost instantly his error—unfortunately, not the error of his racism, but the error in public relations. He had “played the fool,’’ he told a cabinet member afterward, by becoming unnerved in the face of what he considered Trotter’s impertinence. “When the Negro delegate (Trotter) threatened me, I was a damn fool enough to lose my temper and point him to the door. What I ought to have done would have been to listened, restrained my resentment, and, when they had finished, to have said to them that, of course, their petition receive consideration. They would then have withdrawn quietly and no more would have been heard about the matter.’’

But Trotter’s direct action made sure something more would be heard.