Uncovering Mark Lindsay’s musical odyssey to the Rebel Raiders and beyond

“I didn’t have a life. Music was all I cared about doing. When we got off the road, everybody went home to their wives and girlfriends or whatever. I went right to the studio. That was my second home.” Music was obviously an all-encompassing, driving passion for Mark Lindsay.

The still active lead vocalist, songwriter, producer, and arranger of Paul Revere and the Raiders caught the entertainment bug as a four-year-old while boldly harmonizing with his big sister on “You Are My Sunshine” in front of a wildly appreciative Idaho audience, pretty much all spur-of-the-moment.

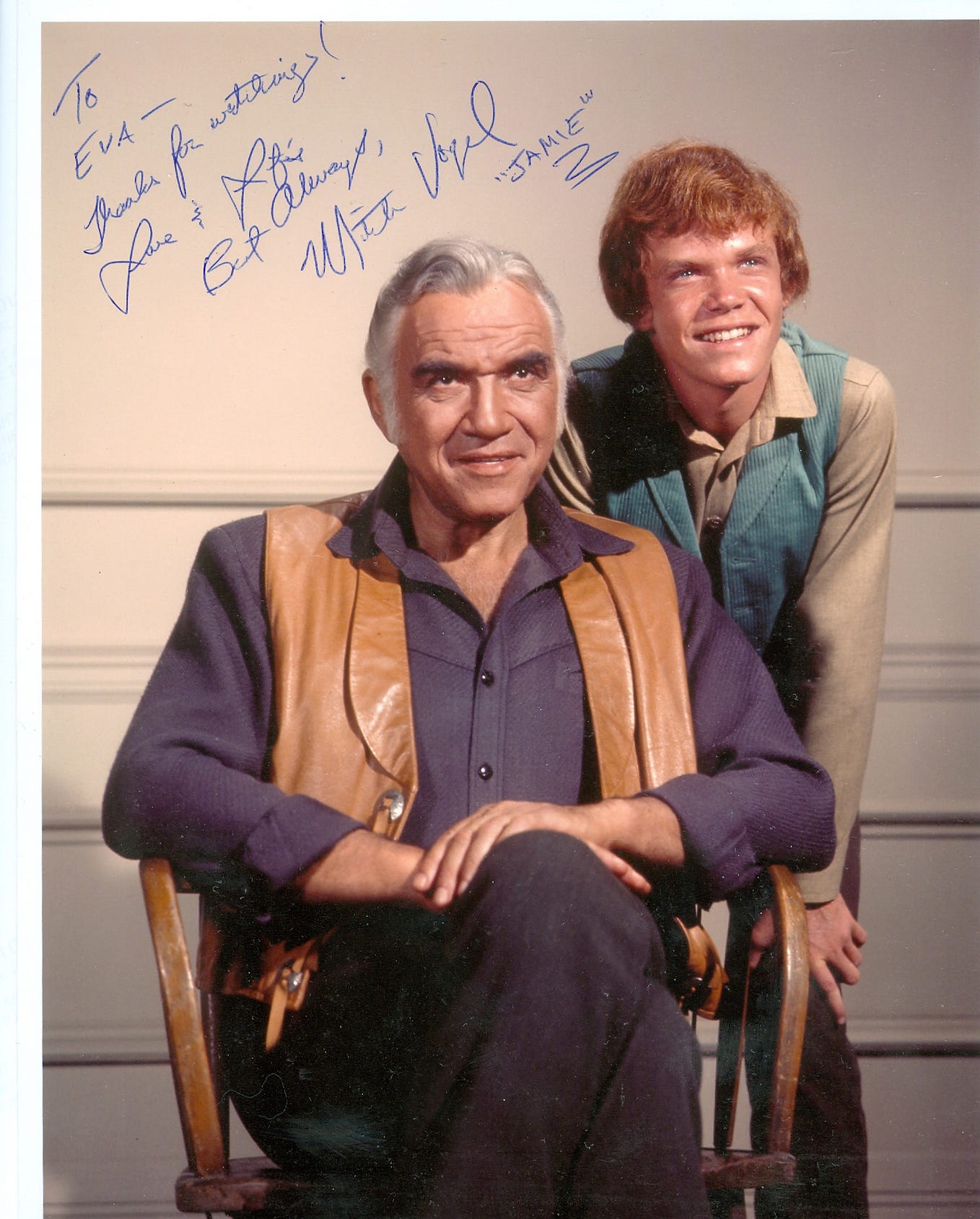

Lindsay largely spearheaded the creative path of the ’60s rockers — the band’s namesake Paul Revere preferred to handle concert and promotional responsibilities with a dash of sterling boogie woogie piano. AM radio airwaves were inundated by the two dozen singles released by the Revolutionary War costume-clad musicians that notched positions on the Billboard Hot 100, spearheaded by “Just Like Me,” “Kicks,” “Hungry,” “Good Thing,” “Him or Me (What’s It Gonna Be?),” and “Too Much Talk.” In the shoulda-been-a-hit category, the Raiders’ original take of intense garage rocker “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone” actually rivals the better-known version served up by the Monkees. Dick Clark even produced two music variety series starring the group — Where the Action Is and Happening.

When the final remnants of the most famous Where the Action Is band lineup imploded in 1967 moments before an appearance on the top rated Ed Sullivan Show, the seeds were sown for three new additions — Freddy Weller, Keith Allison, and Joe Correro, Jr. — talented musicians all coincidentally hailing from the South.

This swampier, more organic incarnation firmly cemented the “Rebel Raiders” latter band phase, perhaps best exemplified on their first gold-selling single, “Let Me.” Critic Lenny Kaye went so far as to give the subsequent Collage album a glowing review in Rolling Stone, although the teenyboppers turned their backs in droves upon taking a whiff of the heavier sounding material. Lindsay has rarely discussed this criminally ignored era in-depth in extensive fashion. That is, until now.

The Complete Mark Lindsay Interview

What makes you laugh?

That question makes me laugh. I don’t know. Probably looking back at a lot of stupid things that I did in the past. I used to worry about whether I was gonna be perceived as being cool or not. That is so unimportant now that some of that makes me laugh.

I also used to try to please everybody. Some people are gonna like you, and some people are gonna hate you. You just have to do the best you can and let the chips fly where they may [laughs]. That’s all you can do.

Is there a certain point where you knew that you wanted to be involved in music?

Oh sure. I always liked music. I remember listening to the radio when I was still in the cradle and still getting fed baby food.

When I was four my mother took my sister and I to a park. She knew we both loved music, and there was gonna be a live band there. She thought it would be a real treat for us to see a live band.

We got there, and the live band didn’t show up. The emcee said, “We’re kinda at a loss here. Does anyone know how to tell a joke, whistle, sing, or do anything?” My mom raised her hand, spoke up, and said, “My kids can sing!”

My sister and I — she was six, two years older than I — got up and sang “You Are My Sunshine” in harmony. I remember the emcee lowered a microphone down in front of my face that looked like it was the size of a football.

When we got through, all the people had big smiles on their faces and clapped. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Wow, this is really cool!’ “Cool” probably wasn’t in my vocabulary at four [laughs], but I wanted to experience that feeling again.

When Elvis Presley broke nationwide in 1956, did you take notice?

Growing up during the pre-rock ’n’ roll era, I fell on the ground when I heard “Heartbreak Hotel.” I thought, ‘Man this is happening.’ Elvis, along with Chuck Berry and Little Richard, quickly moved to the top of my list of favorite singers. I would have loved to have seen a concert where Elvis and Little Richard just tore it up [laughs].

It just so happened that the next year was my last year of junior high school. I had just turned 15. I said, ‘That’s it, I’m outta here.’ I left home and went down to southern Idaho to join a group called Freddy Chapman and the Idaho Playboys. I was a 15-year-old rockabilly singer. Of course, I lied about my age since you couldn’t play clubs unless you were 18. That’s where I got started, and I never looked back.

Do you play any instruments in addition to saxophone?

I write on guitar or piano but you really don’t wanna hear me play them. My skills on piano and guitar are really limited. At one time I actually played rhythm guitar in the Raiders’ very early days.

I found out that I can either sing really well or play fairly well, but I couldn’t do both of ’em worth a crap [laughs]. I just decided to concentrate on singing. Basically I’m a singer/sax player. You would never hire me for say guitar or keyboards in your band, I promise you [laughs].

When guys left the Raiders, who had the responsibility of finding replacements?

From very early on in the band, Revere was always the businessman and I was always the musician. I remember saying, “Look, I’ll handle the music. You handle the business.” He replied, “Great.”

When we needed a lead guitar player way back when the Raiders were still in Idaho, I was the guy that went to Drake Levin’s place. He was a 16-year-old kid from Chicago. I went in and said, “Play me some blues, man” [laughs]. Drake just blew me away. I was kind of the guy that picked the musicians.

Fast forward several years to 1967. We needed a drummer because Smitty [aka Mike Smith] was moving on. We were playing a Dick Clark tour, and there was a group called Flash & the Board of Directors that were opening for us. Joe Correro, Jr., was their drummer.

I said, “Paul, do you see that guy right there? That’s our next drummer.” He said, “No, no, no. I’m not sure he’s good looking enough.” “But you’ve gotta listen to him play!” [laughs]. I handled that because I think I had more of a passion for it than Revere did. It all worked out pretty well.

Was Revere always present on the Raiders’ studio sessions?

No. The last record that Revere played on was “Good Thing” [№4 Pop, November 1966]. Actually, Terry Melcher [the Raiders’ producer-chief songwriting collaborator between 1964 and 1967] replaced Revere’s organ on “Good Thing” [laughs]. The last record where Revere’s contribution was left in the final mix would have been “Hungry” [№6 Pop, June 1966].

Revere was a great boogie-woogie piano player, and our early records benefitted from his presence. When the music changed a little bit and the Beatles, Dave Clark Five, and everybody else came in and started using Farfisa organs, we had to go to an organ.

Revere didn’t like that — he preferred to pound the keys. When he couldn’t do that anymore, he kind of lost his passion for music. He would sit there and play, but it really wasn’t what he liked to do.

Once in a while he’d come to the studio. But mostly, I’d say, “Okay, here’s our next record, Revere.” Keith Allison would go over and show him how to play it, and he’d learn it for the road. You have to bear in mind that Revere had decided to move back to Idaho. He already had a family, including a couple of kids.

How does the latter-day “Rebel Raiders” lineup [i.e. lead guitarist Freddy Weller, bassist-guitarist-keyboardist Keith Allison, and drummer Joe Correro, Jr.] stack up today?

They were really good. Joe Jr. was the best drummer that we ever had in the Raiders. “Kicks,” “Hungry,” “Just Like Me,” “Steppin’ Out,” and “Good Thing” were recorded by the original lineup: Smitty, Drake, Phil “Fang” Volk [bass], Revere, and myself.

After “Good Thing,” we had the television show, Where the Action Is. We were gone like 250 nights a year. We weren’t on the road — we were filming a television show. We didn’t have a lot of time for recording, so Terry Melcher began to use studio musicians.

I didn’t have a life. Music was all I cared about doing. When we got off the road, everybody went home to their wives and girlfriends or whatever. I went right to the studio [laughs]. That was my second home. That’s where I wanted to be.

Terry and I would start other tracks. The other Raiders just wanted to relax a minute. They didn’t wanna go in the studio and record. Terry began to use the Wrecking Crew and various other guys. That lasted until Terry finished producing us.

[Author’s Note: According to Lindsay in the 2010 liner notes of Paul Revere and the Raiders: The Complete Columbia Singles, the label demanded a new single during the 1967 Christmas holidays. Melcher, whose mom happened to be legendary all-American girl Doris Day, was on vacation in Europe. Lindsay quickly obliged by writing and producing “Too Much Talk.” The A-side landed inside the Top 20, becoming the band’s best chart position in six months. Melcher was none too pleased, and ego problems — displayed by both artist and producer — led to the latter’s decision to relinquish his position].

Shortly after “Too Much Talk,” Keith, Joe Jr., and Freddy came into the group. I realized that they were all really good. I realized what an exquisite drummer Joe Jr. was, what an excellent bass player Keith was…if you get a bass player and drummer that can kick ass together, you have the foundation.

The Raiders actually notched five gold albums, but the only gold single that we ever got was for “Let Me” [No. 20 POP, April 1969]. Keith, Joe Jr., and Freddy were the lineup on that single. We have since had a couple of records that have gone gold. I can’t remember them all, but “Kicks” and “Hungry” probably fall into that category.

I used Keith, Joe Jr., and Freddy pretty much right up to the end as much as I possibly could. They were good, especially Joe Jr. The man is just a monster drummer. He was a soul drummer, jazz drummer, and a heck of a rock ’n’ roll drummer. Greenwood, Miss., the boy hailed from [Weller was from Atlanta and Allison grew up in San Antonio, Texas, hence the “Rebel Raiders” nickname].

What would a typical Raiders session be like with Joe Jr., Freddy, and Keith?

Basically, we’d go in the studio and sit around the piano. I’d show the guys the tune. Joe Jr. usually had a set of sticks or brushes, and he’d be playing along on a bench or chair. Keith and Freddy would probably have guitars to kinda figure out the chords.

We’d all kind of learn the song, and then we’d go in and cut the basic track with drums, bass, and sometimes a rhythm guitar. Once we got that foundation down, we just starting overdubbing stuff with some rhythm guitars, keyboards, lead guitar or whatever.

Perhaps a tough question — can you recall the very first song that you wrote?

Actually, it was probably an early version of “Steppin’ Out” [№46 Pop, August 1965]. When I was about 15 years old, I got some ideas for the lyrics but I didn’t really finish it for another couple of years.

How would you characterize your songwriting approach?

I’ve always been a lyricist. In my compositions I’ll usually do all of the lyrics and between fifty to eighty percent of the music. It’s no chore — it’s just what comes out. I did all the lyrics for “Freeborn Man” and basically most of the stuff that Terry Melcher and I wrote.

Terry and I might come up with a hook together, like “Him or Me, What’s It Gonna Be? [No. 5 POP, April 1967]. I would write the rest of the song. Words have always come fairly easily, and I thank God for that. It’s a gift.

Why was “Freeborn Man,” an album cut on Alias Pink Puzz [August 1969], not released as a single? Artists ranging from Jerry Reed, Glen Campbell, Hank Williams, Jr., and Bill Monroe have covered the ubiquitous country ode depicting the life of a working musician.

Looking in retrospect, I think you’re right. As a matter of fact, whenever I mention “Freeborn Man,” they say, “You mean the Bill Monroe song?” [laughs]. Bill Monroe played that song so much, and he used to open his show with it. Now it’s like everyone thinks that he wrote it. “Actually, Bill didn’t write that — I wrote it.” “Oh, really!”

It’s just one of those natural songs. Keith Allison and I were sitting in a Holiday Inn in Greensboro, North Carolina, before a show if memory serves me correctly. I was sitting on the air conditioning unit, and Keith had his Everly Brothers Gibson guitar.

I asked Keith, “Give me a G chord.” The moment I heard the sound, I already had the line, “I was born in the northwest 25 years ago.” The lyrics just spilled out, just as fast as I’m telling you right now. The song wrote itself in about five minutes [laughs], and we had it.

Do you recall the origin of another album cut from Alias Pink Puzz entitled “The Original Handy Man?” You wrote that one all by yourself. Seems like it would be a natural fit for a live setting. Everything about it, from the band’s locked in groove to the swagger demonstrated in your vocal, is killer.

I know the song very well. It’s a great R&B song. It sounds like something I might have written in Memphis when I was doing the Goin’ to Memphis album [February 1968; although credited to the Raiders, it is considered a solo Lindsay effort]. I really got into that whole R&B thing there with Chips Moman and the Memphis Boys. I thought it was a really kick ass track.

Most of my time spent touring nowadays is with the Happy Together package tour. Everybody, including Flo and Eddie of the Turtles and oftentimes Monkee Micky Dolenz, has a half hour slot. I have to stick to the hits like “Just Like Me,” “Steppin’ Out,” “Hungry,” “Kicks,” “Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian),” and “Arizona.” I can’t really get into any album tracks. But, if we get rich and famous again, and I can do an hour or two hour concert, I’ll throw that in for ya.

I listened to Collage, the Raiders’ 12th studio album [March 1970], shortly before calling you. You guys were absolutely on fire as a tight recording ensemble.

I have to admit…some of the tracks were recorded with the Raiders, and some of the tracks were session guys that arranger John D’Andrea brought in. Still, it was a pretty adventurous album [laughs].

How would hard Collage rockers like “Boys in the Band” and “Just Seventeen” go over when you performed them live?

Good kick ass rock ‘n roll is kick ass rock ‘n roll. Those songs were pretty bold, and we did a pretty good job with them live. I remember I went out with a group called Instant Joy when the Raiders weren’t touring one summer and opened for the Carpenters.

We did “Just Seventeen” and “Boys in the Band.” We did all that stuff [e.g. “Gone Movin’ On” and “Dr. Fine”], and we rocked hard. As a matter of fact, we rocked so hard that I’d get standing ovations.

When the Carpenters came on, everybody went, “This is nice, but where’s the rock ‘n roll?” How do I say this? It was not a very compatible package. We just tore the audience up. By the time the Carpenters came on, everybody was exhausted [laughs].

About three weeks into the tour, they canceled me and hired Mac Davis. With an acoustic guitar, he was a much better match. I loved the Carpenters. I think Karen’s voice is one of the top five female voices of almost all time. But if I were a promoter, I would have said, “Get Mark Lindsay out of there and give me Mac Davis” [laughs].

Hopefully this interview will cause readers to discover the wonders of Collage. It was the band’s worst-selling album on CBS/Columbia up to that point [No. 154 POP].

When we did that album, it was my attempt to try to move the Raiders forward. After 1968, the music began to change. Everything got a little more complicated — a little more hard edged. I went to Clive Davis, the head of CBS, and said, “We need to do an album and try to move the Raiders into the 1970s.” Clive agreed.

I put my heart and soul into the making of Collage [Lindsay produced, arranged, and had a hand in writing 9 of the album’s 11 cuts]. Unfortunately when it came out, the Raider fans — the ones who knew who Paul and the Raiders were — didn’t understand it.

It was a little bit past what they were used to. The new fans I was trying to gather in saw the name Paul Revere and the Raiders and thought, ‘That’s not gonna be very heavy’ and didn’t even pay attention to it. Collage kind of got lost in the shuffle.

I should have gone to Clive again and said, “Look, they didn’t get it on this one, so let’s do another album. If they don’t get it on that one, let’s do a third album. If I can’t educate them by the time that we do the third album, I’ll throw in the towel. But let’s try two more albums.”

Clive probably would have gone along with that because it’s really hard to change — make a total, instant left turn — and get everybody to follow you. But I didn’t do that. It just tore me up that I worked that hard and put that much into it and nobody cared.

We did receive a wonderful review from Rolling Stone. As a matter of fact, it’s the only album the Raiders ever did that got a review in the rock magazine. I’m paraphrasing here but critic Lester Kaye said something to the effect of, “Man, this is incredible. If you think the Raiders are pansies or soft, man, forget it. They have arrived. With Mark Lindsay at the helm, they are kicking ass. Wow.”

It was a glowing review. I thought, ‘Thanks, man.’ Of course, again Raider fans didn’t understand it and people that weren’t Raider fans didn’t buy it. So there you go. We got lost in the shuffle. The Rolling Stone review is all I have left [laughs].

Did Clive Davis and CBS/Columbia do a good job of supporting the Raiders?

They did a very good job until the music changed, and we couldn’t bring the Raiders along. The label began to go with the next crop of artists. I remember Clive called me into his office one day and said, “Mark, you have a great future as a rock ‘n roller, but I think you have a better future as a ballad singer. Let me play you a song.”

He played me the song that became “Mandy” [Barry Manilow’s debut number one single in October 1974]. “What do you think?” “Well, it sounds like a hit to me.”

Clive continued, “I really want you to leave the Raiders and become a solo artist.” “Man, I don’t know about that. I love Frank Sinatra, Johnny Mathis, and all that stuff. But my heart’s in rock ‘n roll, and I don’t think I can do this, Clive.” He replied, “Well, okay.” I give him credit for being there and always being very supportive.

Can you think of any songs that you turned down that later became hits?

Johnny Rivers had a big hit with “Swayin’ to the Music (Slow Dancin’)” [№10 Pop, June 1977]. I listened to the music and thought, ‘I’m not sure that’s a hit.’ It was a smash, of course. But I was pretty good at pickin’ hits on most songs. “Slow Dancin’” is one that I missed. You can’t win ’em all.

In the liner notes to Mark Lindsay: The Complete Columbia Singles [2012], I was amazed to discover that before releasing a single, you had an innate ability to determine the chart position within ten points.

True. I could say, ‘This is going to be Top 20’ or ‘I don’t see this one going any higher than No. 12.’ I could get within ten points, usually.

I was lost when “Indian Reservation” came out. I said to myself, ‘This is either the biggest single the Raiders have ever had or the biggest stiff I’ve ever produced.’ I totally couldn’t call it. That’s the only song where I had no idea. Sure, I thought it was wonderful, but I was just so close to it…

What are your memories of “Powder Blue Mercedes Queen?” Besides you, there were two co-writers listed on the second single taken from the Country Wine album named Richard Brian Burns and Robert Seller.

That was a track that Richard and Robert had submitted to me — just the musical track. The original musical track submitted by them was already there pretty much. I wrote the lyrics and then the Raiders recorded it.

The Raiders had a secretary named Bunny. She was the secretary for Tam Music which was one of our subsidiary companies. She had a girlfriend named Bonnie who had a crush on me. She showed up one day in her new Powder Blue Mercedes. It was not a coupe but a sedan. Bonnie had a wild side, and the song kind of evolved from that [laughs].

The propulsive, guitar-laden rocker was the Raiders’ last single to gain any significant chart traction on Billboard [No. 54 Pop].

I have to say that CBS did promote that a lot. On college radio they really kicked that one. I was disappointed that it didn’t go Top Ten. You know what? I’m not sure that I had a chart position in mind for that one because I can’t remember whether I thought it should have gone further or not. I thought it was a real kickin’ track.

Who played on “Powder Blue Mercedes Queen” — studio musicians or the Raiders?

Now you’re testing my memory. Actually, I think it was studio guys that I had run into working with John D’Andrea on Collage.

The penultimate single released by the Raiders before you departed the band was the obscure “Love Music,” co-written by Dennis Lambert and Brian Porter, a production team then in the midst of a hot streak. They were responsible for rejuvenating Glen Campbell’s recording career with “Rhinestone Cowboy” as well as producing comeback hits for the Four Tops and the Righteous Brothers. “Love Music” is a prime pop song with seemingly every ingredient required for a hit, yet it barely dented the charts [№97 Pop, December 1972]. The backing vocals are especially intricate.

Thank you because that’s all me. I did all the background vocals on that record. I found “Love Music” on somebody’s desk at CBS. It was (1: A great song and (2: A great message. I thought, ‘You know what? We do need more love music.’

I went it and cut it. I was just messin’ around in the studio. I kept adding parts and came up with all the backgrounds. You’re gonna hear Mark Lindsay sing about as high as he possibly can on that record.

Without promotion you can’t make things happen. Or maybe the failure of “Love Music” had to do with timing — it’s everything as they say. I agree with you. I thought it was a good record as well as a good performance. I still like it today.

Credited to the Raiders featuring Paul Revere and Mark Lindsay, a ballad called “Jody” is the theme of Santee [September 1973], perhaps best known as Glenn Ford’s last starring role in a Western. As of this writing, fans can only hear it in the film.

I remember the movie. I know the name of the song, but I couldn’t hum even two bars of it. I don’t remember how it goes at all. I haven’t heard it since I did it many, many moons ago as they say. Time flies when you’re having fun [laughs].

After the release of your final album with the Raiders, Country Wine [March 1972], the band continued recording a handful of singles into 1973 like “Song Seller,” “Love Music,” and “(If I Had It To Do All Over Again, I’d Do It) All Over You.” Three other songs confirmed as being recorded during that time period are “Chain of Fools,” John D. Loudermilk’s “Tobacco Road” [a hit for the Nashville Teens in 1964], and “Angels of Mercy.” Fans had to wait nearly 20 years before an official release of the three compositions on The Legend of Paul Revere anthology in 1990. Perhaps there are more unreleased recordings. Why were they relegated to the vaults?

The Raiders were kinda at the end of our bell-shaped curve at CBS/Columbia. We were no longer the most popular band in the world [Author’s Note: The ominous, stinging ‘Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian)’ arrived in February 1971, ultimately earning platinum status after Paul Revere drove cross country via a “cool Excalibur car that looked like a 1927 roadster” relentlessly plugging the song. The slick middle of the road follow-up, ‘Birds of a Feather,’ proved to be the band’s final Top 40 single, stalling at №23 in August 1971].

CBS/Columbia [i.e. label president Clive Davis] had lost interest in promoting any Raider records or spending money promoting the Raiders. They seemed content to let our contract run out. That’s speculation, but that’s the only explanation I can give you that can make any sense regarding why we never released those cuts.

What was your final recording session with the Raiders?

I was fed up with the way things were going with CBS at the time. I had discovered that all the money that I’d made on “Arizona” and my solo projects had been cross collateralized with the Raiders’ earnings. Since the Raiders weren’t earning that much in the latter years, basically it ate up all my royalties.

I went in to get my royalties, and the label admitted [adopts a huckster affectation], “You don’t really have any royalties because we kinda cross collateralized…” “Wait a minute, do you mean there’s nothing there for “Arizona,” “Silver Bird,” and all my recordings?” “Not really.”

I found an unreleased Bob Dylan song written at the beginning of his career called “(If I Had to Do It All Over Again, I’d Do It) All Over You.” That was the last thing I cut with the Raiders [recorded on June 21, 1973]. It was released as an A-side but didn’t really do much. I thought Dylan’s lyrics possessed a perfect sentiment for the way I was feeling. My performance was heartfelt, I promise you [laughs].

Joe Correro, Jr. and Freddy Weller had departed the Raiders by the time “(If I Had to Do It All Over Again, I’d Do It) All Over You” was recorded. Can you recall if Keith Allison, who remained with the band through April 1975, participated on those final sessions?

Keith played really good bass, guitar, and keyboards, and he played on a lot of stuff. I can’t remember whether Keith is present on the last record or whether it was all studio musicians. I was ticked off about the whole thing by the time we tackled “All Over You.”

Have you played with Keith, Freddy, or Joe, Jr. in recent years?

I haven’t. I jammed a little bit with Joe Jr. about 18 years ago, and he was still as good as ever. I haven’t played with Keith or Freddy. As a matter of fact, I did a concert in Jacksonville, Tennessee [October 2013]. Freddy happened to be on the bill. I hadn’t seen him in years. That was extremely fun.

Were any of the Raiders on your solo sessions?

None of the Raiders were on any of my solo stuff. Jerry Fuller was my producer, and he had his own group of session musicians that he liked to use. Mainly from the Wrecking Crew — guys like renowned drummer Hal Blaine.

Jerry Fuller penned two dozen songs for Rick Nelson, encompassing such enduring ballads as “Travelin’ Man,” “Young World,” and “It’s Up to You” (he also sang backup vocals on countless early ’60s Nelson sessions with a wet-behind-the-ears Glen Campbell). When you began your solo career in April 1969 by covering Jimmy Webb’s “First Hymn from Grand Terrace,” Fuller had transitioned into staff production at Columbia. You guys seized upon a winning combination, with Fuller producing all of your solo hits including “Arizona” and “Silver Bird.” It begs the question — did you know Rick?

Absolutely. Rick was a really, really nice guy and very, very talented. Personally, I think Rick was not as highly rated as he could have been because of his background — ‘Oh it’s that kid from the Adventures of Ozzie and Harret show.’

He possessed a clearly unique voice — very soft, but had a lot of character. I liked Rick’s material. He’s one of those artists that left us much too soon. You hear horrible stories and terror tales about people’s true personalities, but Rick was just one heck of a nice guy.

I honestly don’t understand why your cover of Bread’s “Been Too Long on the Road” [No. 98 POP, April 1971] didn’t become a hit record. The early ’70s AM rock staple never released it as a single. Long story short, I felt you vocally improved on Bread’s original version, and your production itself lent a greater air of dramatic intensity.

“Been Too Long on the Road” was written by Bread’s lead singer, David Gates. I must have heard it on one of their albums [On the Waters, July 1970]. I just loved that song. I thought, ‘Man, that’s a smash!’ It was a good record, but it didn’t get promoted. Without promotion you can’t have a hit.

I feel the exact same way about another solo single called “California,” one of your final releases on Columbia [July 1973]. The anguished vocal makes the listener believe that you really experienced those lyrics [e.g. “the glitter and the glamour are turning to rust, the stars on the sidewalk are covered with dust, all the movie lots are just about to go bust, in the whole big town there’s not a soul you can trust”].

I would tend to agree with you. Jack Gold, who was then head of A&R at CBS, suggested I do “Indian Reservation.” He’s actually the guy that first got me started singing ballads. He brought “California” to me and said, “What do you think?” My immediate response: “I think it’s a smash!”

The musicians did a good job on the backing track, and I delivered an okay vocal. CBS unfortunately didn’t promote it at all. You can have the best song in the world and the best performance in the world. If nobody hears it, it just lays there. That’s kinda what happened.

Look, as far as I’m concerned my friend, you can do A&R for me anytime because we both have the same tastes [laughs].

When the Raiders were appearing in front of a nationwide audience on Dick Clark’s Where the Action Is television show in the mid to late ’60s, the band sported the Revolutionary War uniforms. In retrospect, do you think that hindered your artistic credibility in some circles?

Absolutely. The visual image in your mind is the first thing you remember about almost anything. Even today, the first thing people think of when they think of Paul Revere and the Raiders is probably the three cornered hats, long coats, knee high black boots, and costumes [either red, blue, or white].

They forget about the fact that we had some pretty good rock and roll records. In some circles I agree that people tend to consider the Raiders as being a little light because of our costuming. If they just listen to the music, they might change their mind.

Have you ever figured out why the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame refuses to induct the Raiders? Seems like it should have happened 25 years ago.

It’s a mystery, isn’t it? We only had 15 Top 40 records [Lindsay’s solo Top 40 hits are “Arizona” and “Silver Bird”]. There’s a lot of artists in there with two or three hits. It’s beyond me. It may be politics, I’m not sure.

Hey, if they don’t want to nominate Paul Revere and the Raiders, I’ll accept a nomination myself [laughs]. I’m not wearing the costume anymore. Eventually they’re gonna run out of old rockers. As the Yankees used to say, “There’s always next year.” If it happens, the honor will be really bittersweet — Smitty, Drake, and Revere are no longer with us.

Did you have an opportunity to meet Elvis?

I met him a couple of times — once in Hollywood and then years later in Las Vegas. The first time occurred while Elvis was rehearsing for his ’68 Comeback Special, the NBC show where he wore the black leather suit and reunited with original backing cats D.J. Fontana and Scotty Moore.

The Raiders’ road manager was a guy from Memphis named Jerry Williams, a real promoter who knew Elvis and just about everybody connected to him. One June evening Jerry said to us, “Elvis is rehearsing at Burbank Studios on Sunset Boulevard. Come on, let’s go down and see him.”

When we arrived between 9:30 and 10 o’clock that night, Elvis decided to take a break. He came out right on Sunset, standing on the sidewalk leaning against the building. Jerry exclaimed, “You can’t stay out there!”

And this is Elvis Presley, right? He looks like Elvis Presley. Elvis replied, “Look, nobody is gonna believe it’s really me” [laughs]. It was the truth. We’re just rapping back and forth. People came by, and they’d do a double take — ‘Nah it can’t be Elvis’ — and they’d walk on [laughs].

What were the circumstances behind your second Elvis encounter?

It happened in the mid-‘70s when Elvis was playing one of his last runs at the Las Vegas Hilton. He and the TCB Band did a fantastic concert culminating with “An American Trilogy.” He was in all his glory.

I was with my ex-wife who shall remain nameless at this point [Author’s Note: Her name is Jaime Zygon]. She actually was friends with one of Elvis’ girlfriends, Ann Pennington, so we went backstage and got to talk for awhile. He was all revved up from the show, just turnin’ and burnin.’

[Author’s Note: According to the knowledgeable experts at the For Elvis CD Collectors forum, the encounter could have happened near Presley’s Jan. 26, 1974, opening night. His relationship with Pennington was relatively brief, and the Raiders had just concluded a residency at Harrah’s in Reno, Nevada, several days earlier].

Elvis was my idol, and nobody will ever be like him. I would have given anything to have seen him at the Overton Park Shell [renamed the Levitt Shell] in Memphis when he was about 20 years old. Elvis rocked harder than almost anybody.

If he’s in Heaven right now — and I’m sure he is — he’s probably smiling as he looks down and says, “Look how many people are trying to do what I did” [laughs].

Did you get to work in the recording studio with any of Elvis’ band members?

I actually recorded a cover of Aretha Franklin’s R&B classic, “Chain of Fools,” with Elvis’ TCB Band for the Raiders’ still-unreleased final album [tracked between 1972 and 1973]. Jerry Scheff was on bass, Ronnie Tutt on drums, Glen D. Hardin on keyboards, and James Burton supplied lead guitar. There are no Raiders on the recording except me.

We did the session, and James played rhythm guitar on it. I asked him, “Well, can you give me a solo?” “Let me think about it for a minute.” He thought about it for just about a minute. “Okay, I’m ready.” James did the solo in one take — just like flowing water. That’s classic Burton…

Even though Elvis was not there, I used his band, which was almost the next best thing. They were so great live, and they were so great in the studio. “Chain of Fools is such a smokin’ track [listen to it here].

In 2001 you added superb lead vocals to a cover of Roy Head’s “Treat Her Right” for indie surf instrumental guitar band Los Straitjackets. I was disappointed that a full-on Mark Lindsay solo album failed to appear at the time.

“Treat Her Right” is a great song, and I really liked our rendition. I had plans to do more stuff with Los Straitjackets. Something happened, and we never really went too much further with it. Sometimes the best laid plans of mice and men as John Steinbeck once immortalized.

What is your songwriting formula nowadays?

Believe it or not, here’s my formula for writing: I go out and walk between six to nine miles a day. I work entirely in my head. I used to sit down with a guitar or piano and write. I’ve found out that if I don’t write with an instrument, I’m not governed by my inabilities on an instrument. In other words, I can write much, much freer and create more extensive melodies.

You could say I have a recording studio in my mind. When I go out walking I’ll take out a tape of what I’ve been working on, put it on the machine in my head, and overdub or listen to stuff. By the time I get to the studio I have the whole arrangement worked out. After I get about six songs in my head I have to go demo them out because that’s when the hard drive gets full [laughs].

Since the underrated Video Dreams appeared with relatively little notice in 1996, were you writing songs but just not releasing them to the general public?

Actually not that much. Here’s a little story for you: my wife and I have been together for 30 years. We lived in Maui for eight years, Nashville, Memphis, upstate New York, Oregon, Arizona, California, Jupiter, Florida — basically all over the country. We were in Jupiter for two years, but we started gettin’ itchy again.

We pulled down a map and looked at it. I asked Deb, “Where can we go?” She replied, “We have lived in all four corners of the United States, in the middle, and even in Hawaii. What if we get an RV and travel around for a year or two? If we don’t like it, we’ll stop and settle down somewhere. If we do like it, who knows.”

We got off the grid with our RV over a four-year period and made the decision to plant roots in Lubec, Maine, last year. Not coincidentally, in the last five years I have written more songs than I have in the previous 20. They’re good songs. I don’t even watch that much TV anymore; instead, I maintain my daily walking regimen.

I’m pretty much in a renaissance here. I’m rolling with it and having fun. Hopefully if my horoscope is correct, I’m supposed to have a second career in my later years that will out eclipse my first career. We’re gonna stay tuned for that [laughs].

What was the impetus behind tackling Life Out Loud, your first studio album of original material in 17 years?

I’ve done a couple of things here and there [e.g. “Treat Her Right”]. Gar Francis, the leader and guitarist for the Doughboys, asked me to play sax and add backing vocals to the Doughboys’ “It’s a Cryin’ Shame” [Shakin’ Our Souls].

Gar later said, “Do you ever collaborate with anybody?” I replied, “If you send me something down to Florida, we’ll see” (I was living there at the time). Gar emailed me a demo track with a bit of melody on it. I did some lyrics, put a vocal on it, and returned the song to him.

It worked, so we started collaborating. In about two or three months we had approximately 20 songs. I really liked a song that Gar had written a few years earlier for Shakin’ Our Souls called “Rush on You,” so I tackled it. That’s the only song that we didn’t write together.

We soon began recording at House of Vibes in Highland Park, New Jersey. Gar and I co-produced the album. Before the first session, I distinctly remember Gar telling me, “I grew up listening to your voice. When you were 19 or 20 and really rockin’ — that’s how I want you to sing.” “Well, I’ll give it a try” [laughs].

I sang live with the band in the vocal booth. They were so smokin’ that after the first take I came out of the booth. Everybody had big smiles on their faces. I sidled up to engineer Kurt Reil, who also owns House of Vibes and drums and sings in a fantastic New Jersey rock band called the Grip Weeds, and asked, “Was that okay?” “Yeah, we’re not even going to listen to that. Next song.”

We rolled right through the material in two days flat. They were all first takes and vocals. Life Out Loud has that 20-year-old energy on it. I could have done it in 1967 right after I recorded “Hungry.” It was a lot of fun.

I commend you for being able to record the songs in one take. That recording technique seems to be a lost art in modern times.

I can’t take all the credit for it. I will say the band made me do it. For instance, let’s say you do a live show, get so into the music that you forget where you’re at, come offstage, and have no idea what happened. That’s happened to me maybe 25 times in all the thousands of shows I’ve done in my career. Recording this album was just like that.

When the tape was over, I had no idea what I had done. It was just all spontaneous. The rough, basic tracks were so good we kept those as the master and just overdubbed additional instruments and backing vocals on top of them without remixing [overdubs, mixing, and mastering were completed in five days].

It’s not perfect. You can hear guitar leakage or me talking to the band in the background. The vocals aren’t perfect either. I didn’t want to redo them again because they’re so honest. There’s something very real about the guys playing and me singing.

It’s almost like the listener is in the studio with me or being privy to a live concert as far as I’m concerned. I thought it better to be honest than polish it up and make it sound like everything else today. Whether people like it or not, that’s up to them. All I can say is that it’s very real and I like it [laughs].

Are the Doughboys the backing musicians on Life Out Loud?

Yep. Basically all the guys in the band. The bass player, Mike Caruso, played on all the cuts. The drummer, Richard X Heyman, played on about half the cuts. Kurt Reil drummed on the other half. Of course, Gar was omnipresent — guitar and piano/organ on most everything. I sang on everything.

It’s pretty stripped down rock ’n’ roll — rhythm guitar, bass, drums, lead guitar on top of it, and background vocals. I added baritone, tenor, and alto saxophone parts to “I Can’t Slow Down.” I play a nice little sax rock solo on the cut [Mike McGinnis plays sax on the song, too]. Myke Scavone, the lead singer of the Doughboys, played harmonica on a few cuts. That’s it. It’s just like ’60s rock ’n’ roll today

What was special about recording Life Out Loud at House of Vibes Productions?

Kurt Reil has all the vintage ’60s gear — e.g. tube microphones, processors, two equalizers, two limiters — in House of Vibes. Since I’ve had three or four home studios over the years, I also brought what I had in my storage area. Between the two of us, we have enough vintage gear to sound just like we did back in the day.

We didn’t record digitally — we went right to two-inch tape. For today’s kids who grew up listening to digital, they’re used to it and that’s fine. But it’s more organic sounding if you can record the songs in analog format on the front end like we used to do on vinyl. I’m encouraged by the fact that more kids are getting into vinyl.

Sure, it all has to be transferred to digital eventually because it’s gonna be widely disseminated on CD or MP3’s. I can still detect quite a difference upon listening if the artist tracked in analog using vintage recording equipment versus doing everything digitally.

How did you convince Little Steven Van Zandt to appear on “Like Nothing That You’ve Seen?”

We recorded this song prior to the main album sessions. After I recorded my vocal, I went back to my home base in Florida. Gar took the song to Little Steven (best known as the rhythm guitarist for Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band as well as a cast member on HBO’s The Sopranos).

Little Steven said, “That’s good. But we’ve waited 30 years for a new Mark Lindsay single. I want this to be really good. Bring the song to me. I’ve got ideas for some background parts.” Little Steven did indeed add background vocals to it. He and Gar remixed it, too.

I’m very grateful for the heavy rotation that Little Steven gave “Like Nothing That You’ve Seen” on his Underground Garage Sirius XM channel.

What’s the story behind bonus track “Merry Go Round (Christian’s Song?”

Thirteen of the songs are just kick ass rock ’n’ roll. As for the 14th cut, Gar and I wrote a song that just didn’t fit on the album. It was more of a ballad.

There is a very popular novel called Fifty Shades of Grey. Every woman in America has read it and probably a lot of guys, including me [laughs]. I was sleeping on the couch in the studio and woke up around five a.m. one morning and went, “I got it!” In 10 minutes I rewrote the lyrics to “Merry Go Round (Christian’s Song).”

If you read Fifty Shades of Grey, the song will make perfect sense. If you didn’t read the book, then it probably doesn’t make sense [the movie version did big business at the box office in 2015]. The liner notes say, “I was gonna put 13 songs on, but for those of you who are into Fifty Shades of Grey, here’s a 14th bonus cut called ‘Merry Go Round.’” There’s something for everybody on the record. I hope.

I stumbled upon a Twitter photo of you and Brian Wilson taken during the sessions for No Pier Pressure. Did you hang with the Beach Boys creative mastermind in the ‘60s?

It’s funny — I never hung with Brian until recently. I was always so in awe of the man. For so many years I thought, ‘Wow man, hanging with Brian would be like hanging with Elvis!’ [laughs]. I always hung around with his brothers, Dennis and Carl, and the other guys.

The man is a genius, there’s no question about it. He may not sing like he did in the ’60s, but he still thinks like he did back in the ’60s. He still has it…all those harmonies in his head just like he did. There’s only one Brian.

We collaborated on an unreleased song during the sessions for That’s Why God Made the Radio [2012], the first Beach Boys album of original material since Summer in Paradise arrived 20 years before. Incidentally, my good friend Terry Melcher produced the latter album.

It’s the first song we’ve written together. I’m not sure what the title will ultimately be because after the original rough sketch, the song became part of another, larger composition, so there may be a couple of additional writers on it. If I tell you the lyrics, I’ll let the cat out of the bag [laughs]. Let’s just say it’s a love song about a boy and a girl. I haven’t recorded any vocals at this point, but anything is possible. Brian really likes my voice.

What is your perfect day?

Oh boy. You would have to ask me in 20 years because I have a lot of days that are good days. I don’t know what a perfect day would be. Nothing is totally perfect. Everything has a little edge to it.

Nevertheless, I’ll try to answer. The perfect day would just be one where I got up, wrote a hit song [laughs], took a nap, got back up, and wrote another hit song. How about that? A two-hit song day. Sounds pretty perfect to me.

© Jeremy Roberts, 2015, 2016. All rights reserved. To touch base, email jeremylr@windstream.net and mention which story led you my way. I appreciate it sincerely.