Napoleon’s Illegitimate Children: Léon Denuelle & Alexandre Walewski

In addition to his legitimate son (Napoleon II, who appears in Napoleon in America), Napoleon had two stepchildren and at least two illegitimate children: the wastrel Charles Léon Denuelle and the accomplished Alexandre Colonna Walewski. Here’s a look at Napoleon’s illegitimate children.

Charles Léon Denuelle

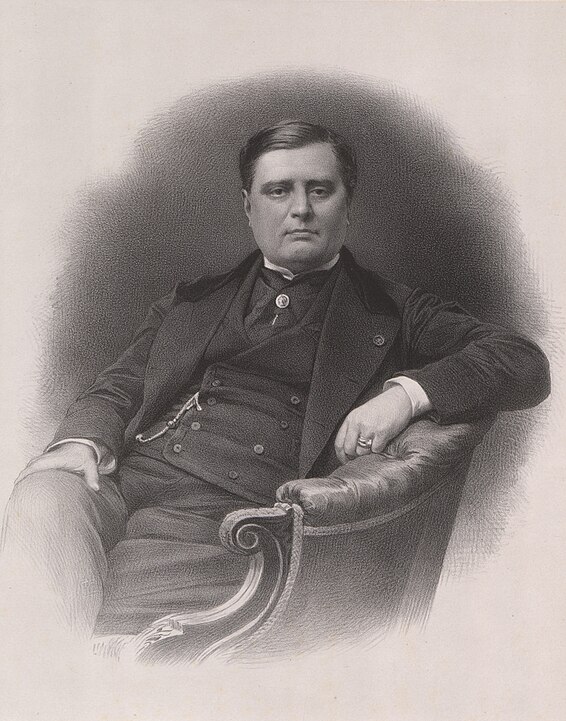

Napoleon’s illegitimate son, Charles Léon Denuelle

Though Napoleon claimed he had only seven mistresses, he probably had at least 21. One of these was Eléonore Denuelle de La Plaigne. Napoleon met her in 1805, when she was a beautiful 18-year-old reader in the employ of Napoleon’s sister, Caroline Bonaparte Murat (Eléonore was also the mistress of Caroline’s husband Joachim).

In April 1806 Eléonore obtained a divorce from her husband, who was in prison for forgery. Napoleon set her up in a house on Rue de la Victoire in Paris. On December 13, 1806, she gave birth to Napoleon’s first child, a boy. Napoleon was delighted, as this proved he was not responsible for his wife Josephine’s infertility. When Eléonore asked for permission to name the boy Napoleon, he agreed to half the name. So the baby was christened Léon, and the birth certificate read: “Son of Demoiselle Eléonore Denuel, aged twenty years, of independent means; father absent.” (1)

Eléonore’s liaison with Napoleon ended shortly after Léon’s birth. In 1808 Napoleon arranged for her to marry an infantry lieutenant. Eléonore’s husband was killed during the Russian campaign in 1812. In 1814, she married Charles de Luxbourg, a Bavarian diplomat.

Meanwhile, young Léon was taken from his mother’s care and entrusted to a series of nurses, paid for by Napoleon. Léon was brought up under the last name of Mâcon, a recently deceased general of whom Napoleon thought highly. According to Napoleon’s valet Constant:

the Emperor tenderly loved [his] son. I often fetched him to him; he would caress and give him a hundred delicacies, and was much amused with his vivacity and his repartees, which were very witty for his age. (2)

Once Napoleon’s legitimate son, the King of Rome, was born, Léon received much less attention, although Napoleon continued to provide for the boy and remained fond of him. In March 1812, the Baron des Mauvières – the father-in-law of Napoleon’s private secretary, Baron de Méneval – was appointed Léon’s guardian. This provided a discreet way for Napoleon to manage the funds he was settling on the child. In June 1815, after Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and subsequent abdication from the French throne, eight-year-old Léon (with Méneval) joined Napoleon at the Château de Malmaison before the latter’s departure for Rochefort and exile to St. Helena.

Léon attended a succession of Parisian boarding schools, with the expectation that he might have a legal career. In his instructions to the executors of his will, Napoleon wrote, “I should not be sorry were little Léon to enter the magistracy, if that is to his liking.” (3) Napoleon also bequeathed 300,000 francs to Léon, for purchase of an estate. This legacy did not immediately happen, as the amount was to be taken from money Napoleon claimed was due to him from the “gratitude and sense of honour” of his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais and his widow Marie Louise. Neither of them came up with the funds, despite a lawsuit by Napoleon’s executor Charles de Montholon.

In 1821, Méneval assumed Léon’s guardianship. This soon became a headache for him, as it had been for his father-in-law, not least because Léon’s taste for luxury and pleasure far exceeded his pocket money of 12,000 francs a year. Méneval hired a tutor, whom Léon disliked. In January 1823, Léon escaped from his tutor while at the theatre and fled to Mannheim, in Baden, where Eléonore and her husband were living. By 1826, Léon was back in Paris and living on his own.

Contemporaries commented on how much Léon looked like Napoleon. According to a British observer, Léon was “tall, five feet six at least, an upright, handsome figure of a man … His origin was stamped upon his face, he was physically the living portrait of the great captain.” (4)

Léon told his uncle Joseph Bonaparte that he possessed “a trifling popularity which I owe to a glorious resemblance.” (5) With his imperial visage, his large income, and his taste for pleasure, Léon cut a conspicuous figure.

He was the prey of parasites and gamblers, an intrepid plunger himself, though sometimes a bad player. (6)

In February 1832, after losing 16,000 francs in a card game and failing to pay up, Léon fought a duel in the Bois de Vincennes against Charles Hesse, a Prussian-born British officer. Though Hesse fired first, Léon’s shot struck Hesse in the chest and killed him. Léon was charged with deliberate manslaughter. A jury acquitted him.

This experience did not deter Léon from gambling. After a brief, undistinguished stint in the National Guard, by 1838 he had wound up (twice) in the debtors’ prison of Clichy. A police report of January 1840 described his living arrangements.

The Comte Léon lives at the Hôtel de Bruxelles, Rue du Mail. He has for mistress a woman of vicious life, living and cohabiting with a married man named Lesieur, a clerk at the War Office, who has deserted his lawful wife for this concubine, who treats him in the most indecent fashion. This self-styled Mme Lesieur follows the practice of magnetism, the proceeds of which business is devoured, as likewise Lesieur’s allowance, by the Comte Léon. … All the tenants of the house are indignant at the scandalous behaviour of the Comte Léon and the woman. (7)

Around this time Léon resolved to visit his uncle Joseph to ask him for money. Méneval warned Joseph:

Léon is going to London, and asks me to give him a letter for you. … He has known reverses of fortune, the details of which I only know imperfectly; if you deign to hear what he has to say, he will tell you the facts himself. They have been caused by the independent attitude he has chosen to assume towards the advice of those who wish him well, and from his own inexperience. He appears to have many schemes in hand and to overestimate his resources, as also the value of a supposed protection exercised on his behalf by the late Archbishop of Paris with Cardinal Fesch. He is a man of enterprising temper, whom prudence and a spirit of rectitude do not always govern. (8)

Joseph decided not to receive Léon based, among other things, on a rumour that Léon was a spy in the pay of King Louis Philippe’s government. Léon’s cousin, Louis Napoleon (son of Napoleon’s brother Louis) also refused to see him. Léon provoked Louis Napoleon into fighting a duel on Wimbledon Common, which was called off only when the police arrived. Léon returned to France, where he survived by begging, borrowing and pursuing lawsuits, including two against his mother.

Something of Léon’s way of life can be gleaned from a February 1848 letter he wrote to General Gourgaud, who had briefly been with Napoleon on St. Helena:

M. Caillieux has insisted on my paying or leaving his house immediately; I was forced to quit my lodgings a few minutes after, with the only garment I had to my back. He has ruthlessly detained my trunk, in which I had packed all my worldly goods, and my papers, as well as a picture of value representing the Emperor at Waterloo. … I am sleeping for the time being in a miserable furnished room at 20 sous a day, where I am very uncomfortable. I am going to beg you, my dear General, to be so kind as to lend me a little money to buy a bed, and I will pay you back as soon as ever I can. I shall be very grateful to you for the loan. (9)

In 1849, Léon founded the Société Pacifique, the object of which was “to organize a series of productive works that may provide the French People with the means of living by the labour of their hands.” (10) He unsuccessfully petitioned the National Assembly for one million francs to support the scheme, which proposed such things as the installation of economical kitchens.

When Louis Napoleon became Napoleon III of France, he refused to see Léon. He did, however, in 1854 decree that the dispositions in Napoleon’s will should be carried out. Léon was given a yearly income of 10,000 francs. Among other things, Léon opened an ink manufactory. He also milked his half-brother Alexandre Walewski (see below) for funds.

Napoleon’s illegitimate son, Charles Léon Denuelle, in his later years

On June 2, 1862, Léon, at the age of 55, married 31-year-old Françoise Fanny Jonet, the daughter of his former gardener. Four of their children lived past infancy: Charles (born Oct. 24, 1855), Gaston (June 1, 1857), Fernand (Nov. 26, 1861) and Charlotte (Jan. 17, 1867).

The family settled at Pontoise, northwest of Paris. Léon died there on April 14, 1881, at the age of 74, of stomach or bowel cancer. He was buried in a pauper’s grave in the local cemetery, marked with a black wooden cross. His remains were later dug up to make room for others. Charles Léon Denuelle has living descendants.

Alexandre Colonna Walewski

Alexandre Walewski in 1832, school of George Hayter

Alexandre Florian Joseph Colonna Walewksi was born in Walewice, near Warsaw, on May 4, 1810 to Napoleon’s Polish mistress, Countess Marie Walewska. Marie became pregnant when she was living near Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, where Napoleon was temporarily residing. When Marie asked to go to Paris to have the baby, Napoleon told her to return to her husband and give birth in his house. Constant writes:

She was delivered of a son who bore a striking resemblance to His Majesty. This was a great joy for the Emperor. Hastening to her as soon as it was possible for him to get away from the château, he took the child in his arms, and embracing it as he had just embraced the mother, he said to him: ‘I will make thee a count.’ (12)

In 1810, Marie and the baby moved to Paris. Napoleon installed them in a house and provided for them, though he ended his affair with Marie in view of his impending marriage to Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria.

In September 1814, when Napoleon was in exile on Elba, Marie (by now divorced) visited him there with then four-year old Alexandre. Napoleon played hide-and-seek with the boy and rolled around with him in the grass. Napoleon reportedly said to Alexandre, “I hear you don’t mention my name in your prayers.” Alexandre admitted he didn’t mention Napoleon, but he did remember to say “Papa Empereur.” Napoleon said to Marie, “He’ll be a great social success, this boy: he’s got wit.” (13)

Along with Méneval and Léon, Marie and Alexandre joined Napoleon for a final farewell at Malmaison in June 1815. In 1816, Marie married her lover, the Count d’Ornano. The following year, when Alexandre was seven, she died. The boy’s uncle ensured that he received a good education.

Shortly before his death in 1821, Napoleon wrote:

I wish Alexandre Walewski to be drawn to the service of France in the army. (14)

This proved prophetic. When Alexandre was fourteen, he refused to join the Russian army (Poland was then under Russian rule). He instead fled to London, and then to Paris. When Louis-Philippe ascended the French throne in 1830, he sent Alexandre to Poland. The leaders of the 1830-31 Polish uprising dispatched Alexandre to London as their envoy. According to Charles Greville, Alexandre “was wonderfully handsome and agreeable, and soon became popular in London society.” (15)

On December 1, 1831, Alexandre married Lady Catherine Montagu, the daughter of the 6th Earl of Sandwich. They had two children: Louise-Marie (born Dec. 14, 1832) and Georges-Edouard (Mar. 7, 1834), both of whom died in infancy. Catherine died shortly after her son’s birth, in April 1834.

Back in France, Alexandre became a naturalized French citizen and joined the French army. He fought in Algeria as a captain in the French Foreign Legion, resigning his commission in 1837 to become a journalist, playwright and diplomat. On November 3, 1840, Alexandre had a son, Alexandre-Antoine, with French actress Elisabeth Rachel Félix, who also had a son with Arthur Bertrand.

On June 4, 1846, Alexandre married Maria Anna di Ricci, the daughter of an Italian count. They had four children: Isabel (b. May 12, 1847, died in infancy), Charles (June 4, 1848), Elise (Dec. 15, 1849) and Eugénie (Mar. 30, 1856).

After his cousin Louis Napoleon came to power as Emperor Napoleon III, Alexandre served as a French diplomat in Italy, and then as French ambassador to London. He arranged for Napoleon III to visit London in 1855, and for Queen Victoria to make a return visit to France.

In 1855, Alexandre became France’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and, in 1860, the French Minister of State. He also served as a senator and, later, as president of the Corps Législatif. In 1866, he was named a Duke of the Empire. Alexandre Walewski died of a stroke or a heart attack at Strasbourg on September 27, 1868, at the age of 58. He is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Alexandre Colonna Walewksi has numerous living descendants.

Napoleon’s illegitimate son, Alexandre Colonna Walewski, in 1860

Napoleon’s other illegitimate children?

According to Napoleon’s valet Constant:

This child [Léon] and that of the beautiful Pole [Alexandre]…are, with the King of Rome, the only children the Emperor had. He never had any daughters, and I think he would not have liked to have any. (16)

This has not stopped speculation that Napoleon had other illegitimate children. Émilie de Pallapra claimed that she was Napoleon’s daughter, resulting from a brief liaison in Lyon between her mother Françoise Marie de Pellapra and the Emperor. However, the alleged timing of their tryst is incompatible with Émilie’s birth date in November 1805.

As noted in my post about Charles de Montholon, Napoleon was probably the father of Albine de Montholon’s daughter Joséphine Napoléone, born on St. Helena on January 26, 1818. Little Joséphine died in Brussels on September 30, 1819.

You might also enjoy:

Napoleon II: Napoleon’s Son, the King of Rome

Napoleon’s Children: Eugène & Hortense de Beauharnais

10 Interesting Facts About Napoleon’s Family

Living Descendants of Napoleon and the Bonapartes

What did Napoleon’s wives think of each other?

- Joseph Turquan, The Love Affairs of Napoleon (New York, 1909), p. 249.

- Louis Constant Wairy, Memoirs of Constant, translated by Elizabeth Gilbert Martin, Vol. II (New York, 1907), pp. 157-158.

- Hector Fleischmann, An Unknown Son of Napoleon (New York, 1914), p. 88.

- Ibid., pp. 156-157.

- Ibid., p. 157.

- Ibid., p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 178.

- Ibid., pp. 182-183.

- Ibid., pp. 212-213.

- Ibid., p. 216.

- The Love Affairs of Napoleon, p. 249.

- Memoirs of Constant, Vol. II, p. 183.

- Christopher Hibbert, Napoleon: His Wives and Women (London, 2002), p. 222.

- An Unknown Son of Napoleon, p. 88.

- Charles C.F. Greville, The Greville Memoirs, Vol. II (London, 1874), p. 104.

- Memoirs of Constant, Vol. II, p. 158.

56 commments on “Napoleon’s Illegitimate Children: Léon Denuelle & Alexandre Walewski”

Join the discussion

This child [Léon Denuelle] and that of the beautiful Pole [Alexandre Walewski]…are with the King of Rome, the only children the Emperor had. He never had any daughters, and I think he would not have liked to have any.

Louis Constant Wairy

An absolutely wonderful article this week – truly fascinating, thank you.

A duel on Wimbledon Common! how exciting – I used to walk my dog on Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath regularly but by then the age of duels was long over!

Superb blogs, please keep them coming.

Thank you, Lally. So glad you enjoyed the article. I once had the good fortune of going for a lovely stroll with friends on Wimbledon Common. It’s fascinating to think of all the duels that happened (or, in this case, nearly happened) there.

Is there any proof of Leon Denuelle’s descendancy? There are different statements about that in the books.

As concerns Marie Walewska’s “memoirs”, they tend to describe her as the “victim” of her patriotism and of the manipulations of others. She writes nothing about her real relationship with Napoleon – and that is not quite honest or fair. One descendant of her marriage with d’Ornano wrote a voluminous book about her affair with Napoleon, which was questioned by a famous French historian in the nineteen fifties. It all ended up in court and the avowal by d’Ornano that he faked a lot of it. Unfortunately, this book is still quoted by a lot of historians – mainly French, although they ought to know better.

Thanks for your comments, Irene. Léon was (and still is) generally acknowledged as being Napoleon’s son. I don’t know whether DNA tests have been done on his descendants to confirm their relationship to the Bonapartes. As for the real relationship between Marie Walewska and Napoleon, the only ones who could comment with certainty on that are Marie and Napoleon themselves, and they both doctored their memoirs for public consumption. I wasn’t aware of the book by Marie’s and d’Ornano’s descendant. Thanks for alerting me about it.

Hello Shannon,

The book by d’Ornano is well used and was criticised by a well known French historian named Jean Savant. There is even a book about their court squabbles called “L’affaire Marie Walewska”, if I remember correctly. D’Ornanos book was translated into English at one time, called “The life and loves of Marie Walewska”, once again if I remember correctly. There is a biography about ALEXANDRE WALEWSKI by Francoise de Bernardy once again. She wrote a lot of very good books about personalities of this period. Concerning Marie and Napoleon, we have a host of comments on their relationship by others who were in a position to know. Napoleon himself was not given to reveal a lot about his emotions for women. The best biography of Marie Walewska to date is considered to be the book by Christine Sutherland, a Polish born now British author, who had access to a lot of Polish archives, knowing the language. The story is still popular in Poland. Sutherland’s book was translated into several languages.

Thanks, Irene, for these great sources about Marie and Alexandre.

I had always thought that Napoleon had no living descendants today. It is fascinating to find that he most likely does.

Yes, it’s really interesting, especially as the legitimate Bonapartes — none of whom are Napoleon’s direct descendants — tend to get more public and media attention. It was nice that the Hermitage Museum in Amsterdam chose the current Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewski (Napoleon’s descendant) to open its exhibit about Tsar Alexander, Napoleon and Josephine (see: http://russia-insider.com/en/story-friendship-war-and-art/5318).

Fascinating read, as always, Shannon. I was familiar with Alexandre Walewski, but the story of Léon Denuelle is news to me 🙂

Thanks, Pier. I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Dear Shannon,

I enjoyed your very interesting article, which I came across by chance.

I am 64 years old and all my aged relatives who would have more information have all sadly passed away. However, I have always been brought up with an old family story, (which may or may not have any truth, although I have no doubt of it being fabricated for any gain) that my great great grandfather claimed he was the son of Napoleon. The story is rather vague, but interesting. My great great grandfather sailed as a young man away from France, his country of birth (I think he may have fallen out of favour with his family) and landed in Rangoon, Burma where he settled and married a young Burmese girl (my great great grandmother). They had a number of children, all girls, one of whom was named Eugine, who later became my grandmother. He visited the King and Queen of Burma and was known as a French aristocrat by the Burmese people. His name was Ferdinand (Fernand?) de Vera. He was known to be very wealthy and had a great patriotic attachment to France, although he was sadly never to return home.

I am not sure whether or not there is any validation to this story, and in a way it has not real importance to my life, although the story has always persisted in my family’s history and it would be nice to have some verification of it simply for interest sake.

I have never ever before persued anything like this before, and I am sure you must have hundreds of replies like mine, but I am sure you’d be interested to know how far the line of heritage can extend!

With very best wishes,

Marie

Thank you for writing, Marie. It’s lovely to hear from you, and to learn of possibly another one of Napoleon’s illegitimate children. I’ve not come across a reference to your great great grandfather in any of the accounts I’ve read. Perhaps another Napoleonic reader has, and will leave a comment. It would be something if Napoleon had Burmese descendants!

I, too, am supposed to be a descendant of Napoleon. I can’t remember the name of the son at the moment. I read an autobiography of a relative that stated that her husband was a grandson of Napoleon’s and they had the papers to prove it. I have found census records of the supposed son with his mother while living in England. She is married to someone, but the son is listed as a stepson. I will have to go to my ancestry site and get the names and details. The lady that wrote the autobiography was quite famous during her time, as a musician, and writer. I found and borrowed the very old book of her autobiography from the Brooklyn library and read the statement for myself.

I went and looked for the names. The son would have been Louis Diehl. The grandson would have been Louis Ludwig Diehl. It was Louis Ludwig’s wife, Alice Mangold, who wrote in her autobiography that her husband was the grandson of Napoleon with the papers to prove it.

I just noticed another ancestry tree that says the mother of Louis, mistress of Napoleon, was Josephine De La Pagerie Tascher.

Thanks, Candice. This is interesting. I’d never heard of Louis Diehl before, but I’ve now searched and found Alice Mangold’s autobiography, where — as you say — she writes of her husband Louis Ludwig Diehl that “his mother had been a German actress of the greatest beauty…. His father had been, as documents in my possession prove, one of the natural sons of Napoleon the First.” (p. 196) If that is the case, Louis Ludwig’s grandmother would not have been Josephine Tascher de La Pagerie. Josephine was Napoleon’s first wife. She had only two children (Eugène and Hortense), and those were with her first husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais. Josephine was unable to have any children with Napoleon, which is why he ended their marriage. I haven’t been able to find any other reference to Napoleon having a illegitimate son named Louis Diehl. It would be interesting to see what’s in those documents that Alice Mangold refers to, if anyone in the family still has them.

I guess I didn’t think too much about the Josephine link, I just wrote what someone else had written on there ancestry.com family tree. You are correct, it couldn’t have been her. It would be interesting to see those documents, but I don’t think anyone still has them as far as I know.

That’s too bad about the documents. Maybe someone reading this thread will know more about who Louis Diehl’s mother might have been.

G’day Shannon, you may be interested in the DNA work ,

Napoleon III’s father was Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon I’s brother and King of the Netherlands. He had been married to Hortense de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s step-daughter (Josephine’s daughter from her first marriage), and neither was happy with the match – Louis was jealous, cold, and Hortense was prone to depressive episodes. The couple often spent large swathes of time apart from each other.

Hortense was known for her infidelities, as a result. At the probable time of their second son’s conception (Napoleon III had an elder brother, Napoleon-Louis who died fighting with revolutionaries in Italy in the Carbonari rebellions), Hortense and Louis were in different countries – except for one day, which supporters of Napoleon III claim was the day of his conception.

Nevertheless, his life and his reign were still marked by rumor concerning his true parentage.

Genetic studies performed to codify Napoleon I’s genetic heritage showed that the descendents of his brother Jerome (King of Westphalia and ancestor to the current Bonaparte line) and the descendents of his illegitimate son through his mistress the Countess Walewska bear his patrilineal genetic marker.

However, Napoleon III did NOT share this patrilineal lineage, meaning he was not descended from Napoleon I’s father Carlo, and consequently not from Louis Bonaparte.

Possible candidates for Napoleon III’s true father include Charles Joseph, comte de Flahaut (the illegitimate son of Talleyrand, one of Napoleon’s chief statesmen and rivals), who fathered one of Hortense’s bastards, the Duke of Morny (a prominent Second Empire politician and orchestrator of the coup that brought Napoleon III into power).

To note however is that under French law at the time of Napoleon III’s birth, the husband of the wife would be the legal father of the child, regardless of true parentage, which in any case could not be proven at the time.

Another possibility is that it is in fact Louis Bonaparte who was the illegitimate one, through his mother Letizia Bonaparte, and Napoleon III his trueborn son.

Sources: “Reconstruction of the Lineage Y Chromosome Haplotype of Napoleon the First,” Gerard Lucotte et al. http://www.ijsciences.com/pub/pdf/V220130935.pdf

“La mort de Napoléon, Mythes, légendes et mystères,” Thierry Lentz and Jacques Macé (2009)

also you may be interested in the following Ref :Journal of Molecular Biology Research .Vol 5. No. 1 2015 http:// http://www.dx.doi.org/10.5539/jmbr.v5n1p1

Thanks, Mike. I had read of this DNA research, which raises the interesting possibility that Napoleon I and Napoleon III were not blood relations. I appreciate you laying out the plausible explanations and posting the links.

Hi my name is Michel Pearl born 21/03/1944

My Brother is Patrick Pearl born 18/06/1957

Our father is Louis Frank Pearl born 19/02/1922 Île-de-France.

Son of Ernest Pearl and Alice Beatrice Vidal Diehl

Alice Beatrice Vidal Diehl is the daughter of Charles Vidal Diehl

Charles Vidal Diehl is the son of Louis (Ludwig) Diehl and Alice Georgina Mangold

Who wrote the book you reference in your notes to Candice. October the 9 2016.

This story is of course of interest to me.

My Business partner loves doing family tree research and uncovered all of this today for me.

At this stage I don’t have a clue of what to do next other than a thought crossed my mind that perhaps my brother and I could have a DNA test maybe that would help a bit with the history of Napoleon.

If you have any thoughts on this could you share them, I would love to hear from you

Thanks for providing this information about Louis Diehl, Michel. Here’s a good article on what you can and can’t learn from DNA testing: https://www.thoughtco.com/dna-family-trees-1420576. Another route would be to see if anyone in the family still has the documents that Alice Mangold refers to in her book.

My grandmother was a Bonaparte and she told stories that her father was French and crossed the sea, met my grandmother and settled for a time on the island of Puerto Rico which was owned by Spain, married and had two children. The only survivor left is my aunt. We did ancestry DNA and the results confirm the story she was told where the origin of the areas in Europe were confirmed.

I’m glad that the DNA testing was able to confirm your grandmother’s story, Rebecca.

Michel, the book is Alice Mangold’s autobiography.

How did Elenore’s age jump from 18 in 1806 to 21 in 1806?

Eléonore Denuelle was born on September 13, 1787, so she was 18 in 1805, and 19 when Léon was born on December 13, 1806.

Candice Petersen thank you for that information.

I will publish what I find

I came across this blog and saw the comment about Napoléon III’s illigitimate birth proved by a DNA research.

It is true that when you see pictures of N III, he doesnt look like a Bonaparte, unlike his cousins, the famous PlonPlon or Charles-Lucien Bonaparte or his half cousins Alexandre Walewski and Comte Léon or even his female cousin the countess Camerata (who really looked like a Bonaparte!!!).

Hortense is the main “suspect” in this case with her famous night in the Pyrénées mountains alone with a charming local guide and with a futur Napoléon III born only 8 months after Louis and Hortense were reunited. But in fact, nothing proves that Hortense had a lover during her stay in the Pyrénées when the baby was conceived (Flahaut was not there and it seems he was not his lover at this time) and the doctor (Corvisart?) who was there when she gave birth reported that the child was premature.

The pictures (ok, it is just paintings) of her second son Napoléon-Louis also show a man who had not the Bonapartes’ features. I don’t think Hortense would have 3 illigitimate sons…

IMO, Laetizia could be considered as the “suspect”. The DNA report says that the N III’s father male roots come from an old Corsican roots (whereas the Bonaparte male’s roots are from the east of the Mediterranean sea, as shows the search on Napoléon, Joseph and Jérôme’ DNA). So there are more chances that Laetizia, as a Corsican, had a lover with old Corsican roots than Hortense who never put a foot in Corsica.

As for Louis, when you see paintings of him or when you read contempories descriptions of him, it seems that he was physically and morally totally different from his brothers (or even his sisters). In fact, many comtempories noted that he looked different.

So who was the father if not Charles? It is well known that Laetizia had a soft spot for the charming Count of Marbeuf, but the man was from Brittany, not from Corsica; so the question is still open.

By the way, nothing to do whith the Bonapartes, but thanks to a DNA research another “big” rumor of the French History has been solved recently: Louis XIII was really the father of Louis XIV…

Thanks, Marieno. Very interesting. I’ve often wondered about this. You make a good case that we should be looking at Louis’ parentage, rather than his son’s.

I am a descendant of Napoleon and Marie Walewska’s illegitimate son Alexandre Colonna Florian Walewski. I am a descendant of Auguste Jean Waleski, Auguste Waleski (according to Bernady Law Firm of England, now closed). Can you shed some light on this? Their son came to India via British East India company. I am not sure of his name. He was my mother’s grandfather.

Nice to hear from you, Nancy. I do not know the details of all of Alexandre Walewski’s descendants. Perhaps one of these family trees can provide you with more information: https://www.geni.com/people/count-Alexandre-Colonna-Walewski/6000000002376187259; and https://gw.geneanet.org/frebault?lang=en&n=colonna+walewski&nz=frebault&oc=0&p=alexandre+florian+joseph&pz=henri. Good luck with your search.

Thank you for your reply. The information I have according to Bernardy law firm is that Auguste Jean Walewski married Marie Ann Emmett in 1837 and their son August Walewski is my great grandfather.

I’m wondering whether that 1837 date is correct, Nancy. Napoleon’s son Alexandre Walewski would have been only 27 years old then, and none of his surviving children were born before the 1840s.

did Charles Leon have a address at 222 Rue de davel Paris ? davel may be miss spelled by the letter “d”

That I don’t know, Albert.

I am a Walewski. My grandfarther, Ludwig Walewski was born in Poland in The late 1890’s. Settled in Detroit, with brothers in Pittsburgh. We have done some research and we think we may be relatives of Alexandre. Might this be a possibility?

It’s possible, Kevin. You might want to visit the Colonna Walewski family website to see if there is some helpful information there.

Hello, I recall in the summer of 1971 when I was 11 my family and I were on holiday in Cornwall, England. We saw a flyer on a wall outside an old house explaining that the house had a room which had been recreated as the inside of Napoleons campaign tent as it looked at the battle of Austerlitz. And that there were two descendants of Napoleon living there. Well, I had seen the film ‘Waterloo’ 1970 starring Rod Steiger as Napoleon. And I was hooked on anything Napoleonic buying books etc, and toy soldiers of the period.

So I suggested to my family we all go there to see it. On opening the door there was a lady who looked just like Napoleon and her sister who also had a resemblance. They were not English possibly Polish or Italian? The display of Napoleons campaign tent was excellent with some antique items that belonged to him. We all thought the resemblance to Napoleon was uncanny and we have always remembered the encounter.

On reading your website it jogged my memory. Could these two have been descendants of Leon?

Martin.

That’s interesting, Martin. I don’t know who the ladies were. It’s quite possible they were Leon’s descendants.

Good afternoon,

In 1821, around Independence Day, when Great-grandfather was not yet Emperor, he was seen in Costa Rica… What was he doing there? No one knows.

My 4th great-grandfather Napoleon III did have a daughter. From what I see, probably, the “only daughter.”

My 4th great-grandmother Lady Paula Saldos De Padilla was a Spanish woman who lived at Saint Michael, El Salvador back in her days (she was a businesswoman of Indigo and other produce).

Paula gave birth in 1831 to Napoleon Saldos and 1835 Enriqueta I Saldos (great-grandfather DID NOT give them his surname. No none of his children living in the EXILE did he ever mention them back in Paris.

He then went back to Saint Michael in 1844 (exile?)

His excuse to have innocent women like my great-grandmother fall easily for him, was because he might have used the same lame excuse:

“I need an heir”.

Nice to hear from you, Duchess. Thank you for these interesting details about your family.

Quite interesting history. My mums family claim that they are part of Napoleons family as I went through Napoleons history I can’t find anything of the Blanche in South Africa. If they are part of Napoleons family can any one tell me how did they end up in South Afrika. I would love to hear from you.

Thanks for commenting, Saret. I don’t know if any of Napoleon’s descendants are in South Africa.

Thank you Shannon. Where can I find out?

I don’t know, Saret. Maybe someone reading these comments will have some helpful information for you.

I did a brief search of the internet and found nothing sorry☹

Thanks for searching, Devin.

So glad I stumbled upon this blog. Thank you everyone for all the information that has added a whole new dimension to Napoleon Bonaparte. I saw the death mask of ‘The Eagle’ at Schoenbrun, Vienna, twenty years ago; a sad story in itself.

Nice to hear from you, Suzy. So glad you’re enjoying the blog.

So the story goes, Marie and Alexandre had to depart Elba more secretively than they arrived, which involved leaving on a ship in very very horrible stormy weather – which caused Napoleon much anxiety in wondering if his close kin would survive their voyage.

Thanks for mentioning this. I read that Napoleon was so worried that he sent an order to the port to delay their departure, but it arrived too late.

My great great great uncle, Thomas Sutcliffe Mort, sailed from England to Australia in 1937, and kept a detailed diary throughout the voyage. His entry for Friday 24th November, when the ship was at Tristan Da Cunha, contains the following: “Phillips, a lad bearing a great resemblance to Napoleon, was born on St. Helena, and was left at Tristan by a whaler. He is a good whistler and a good singer, he sadly wanted to come back with us”.

Interesting! Thanks, Ian. That sounds like a wonderful diary.

Quite amazing as I just stumbled upon this article. Our former apartment in Vienna was the residence of Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewska. The apartment below us was the French Military Attaché.

That’s so cool, Karlo! Glad you found the article.