- Photo:

- Unknown author; maybe Charles Clyde Ebbets

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

The Actual Stories Behind Famous Historical Photos

Copy link

Every picture has a story behind it. Sometimes the stories behind famous photos are well known; other times they're lost to history. The photograph itself might even be the only thing that remains to tell viewers about something in the past.

Some of the most influential and important photographs in history attest to human ingenuity, social change, or political revolution. They depict cultural icons and historical events that are familiar to viewers. Then again, famous photos can also be shrouded in mystery, intriguing and familiar, but still full of more questions than answers.

Vote up the historical photos that, in the end, need at least the proverbial thousand words to tell their story.

- 11,541 VOTES

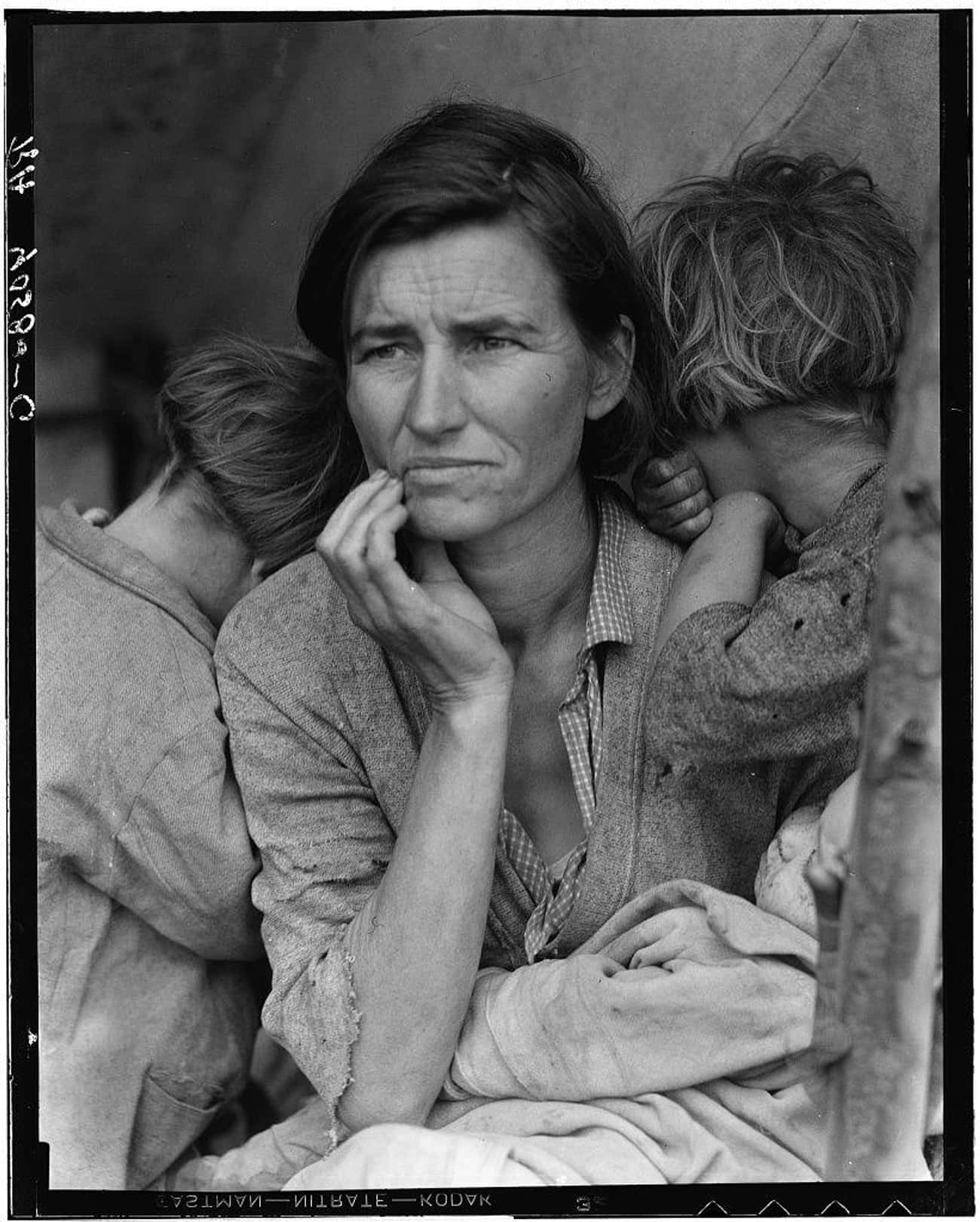

1936: Dorothea Lange's 'Migrant Mother'

Photographer Dorothea Lange chronicled the Great Depression while working with the Farm Security Administration. Lange, an agent of the New Deal, was tasked with bringing the plight of America's rural poor to light.

Her picture of Florence Owens Thompson, known as Migrant Mother, was one of seven images Lange took of the 32-year-old woman in Nipomo, CA. Thompson and her seven children lived at a pea-picking camp where, according to Lange, they were surviving on "frozen vegetables from the surrounding field and birds" felled by the children.

Overall, Lange's work - especially Migrant Mother - captures the struggle and strength of individuals living through the Depression. Thompson's expression highlights the concern she felt; the turned heads of the children reveal their dependence on their mother; and the dirty and frayed garments indicate multifaceted levels of despair.

Paul Taylor, Lange's husband, marveled at how Lange would "saunter up to the people and look around, and then when she saw something that she wanted to photograph, to quietly take her camera, look at it, and if she saw that they objected, why, she would close it up and not take a photograph, or perhaps she would wait until... they were used to her."

One of the Thompson children, Katherine, later recalled Lange telling her mother that the picture would help others and that their names would not be used. When the picture was published in the newspaper, however, Katherine was "ashamed of it. We didn't want no one to know who we were."

- 21,482 VOTES

- Photo:

- Draper Laboratory; restored by Adam Cuerden

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

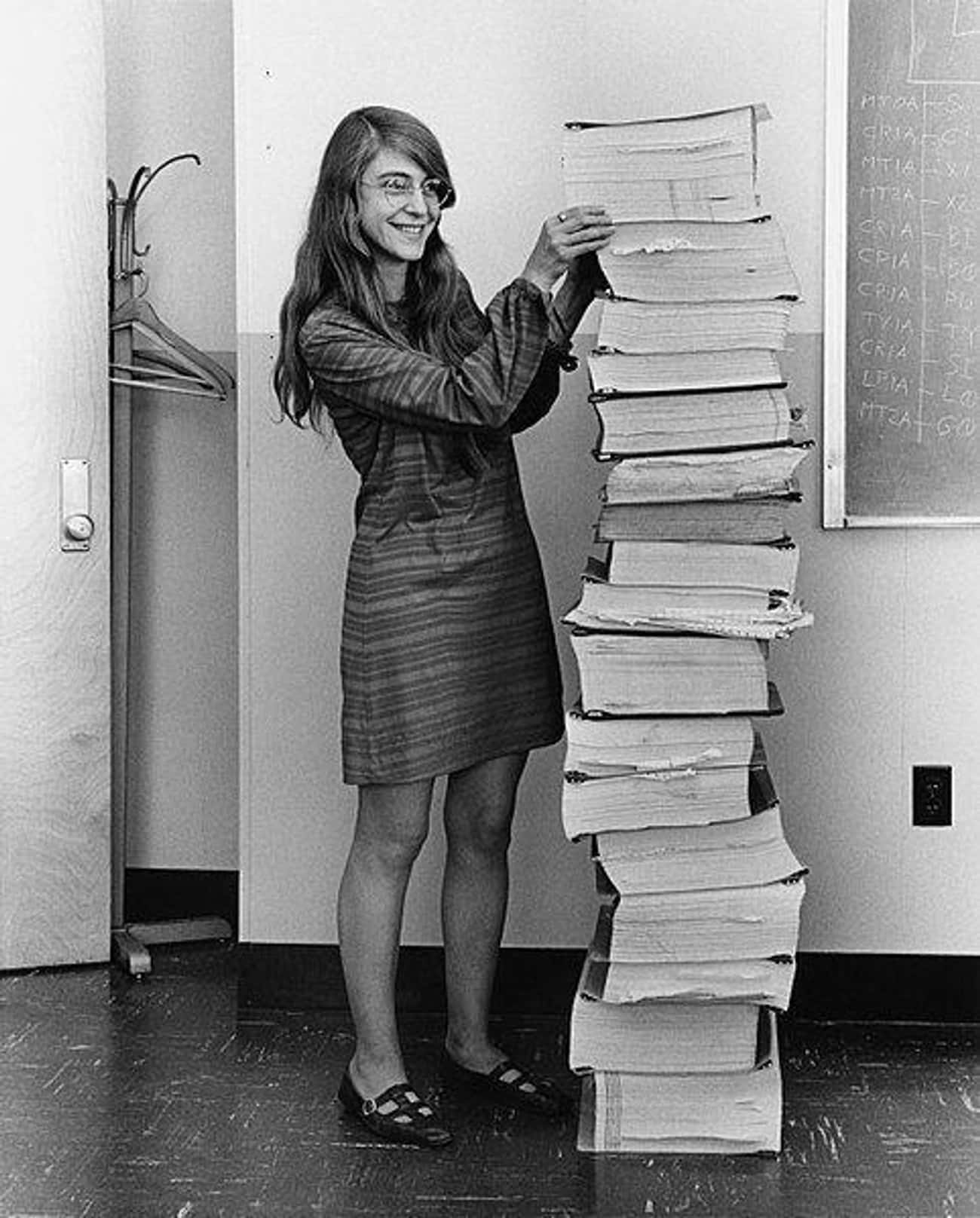

Former schoolteacher Margaret Hamilton took a job as a software programmer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during the late 1950s. Initially tasked with working on meteorological and defense-system software, Hamilton transitioned to aeronautical technology at the Instrumentation Laboratory at MIT (later called the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory) during the mid-1960s.

In 1965, Hamilton was appointed head of the team that would write and test software for the two computers on NASA's Apollo 11 mission - the Columbia (on the command module) and the Eagle (on the lunar module). With roughly 100 fellow software engineers, Hamilton incorporated protections into the software to prevent previous mistakes.

When a staff photographer took the picture of Hamilton with volumes of software information in 1969, it not only highlighted the pioneering technological achievement, but also emphasized the role of women in the process. Hamilton commented in 2019:

Programming was never considered to be women’s work, at least not in any of the many projects I have been involved with. Human computers [who did calculations by hand] were mostly all women and there were women who used calculating machines... but they weren’t programmers... Then within a couple of years there would be a few - and I did have some working for me - but not many. There were always many more men.

- Photo:

- 32,145 VOTES

1936: One Man's Refusal To Take Part In A Salute

- Photo:

The defiant man who refused to salute while surrounded by Nazi loyalists, seen here in a 1936 photo, might be one of two people: August Landmesser or Gustav Wegert. Whoever the man is, he was present at the launch of a Horst Wessel, or naval training ship, on June 13.

If the man is Landmesser, his refusal to salute could indicate his personal circumstances and SS ideology. Landmesser joined the party in 1931, hoping it would help him find a job, but wanted to marry a Jewish woman, Irma Eckler, in 1935.

Race laws at the time prevented the nuptials, but Eckler and Landmesser continued their relationship. They had two daughters, Ingrid and Irene, and tried to flee Germany in 1938. Eckler was likely detained and sent to a concentration camp where she later perished. Landmesser was imprisoned and sent to fight on behalf of Germany. It's believed he died on the battlefield in Yugoslavia.

If the individual in the picture is Gustav Wegert, his life has some similarities Landmesser's. According to the Wegert family, Gustav was a metalworker at the Blohm & Voss shipbuilding factory in Hamburg, Germany. He, too, attended the launch of the Horst Wessel, but at no time in his life saluted the Third Reich.

In the aftermath of not saluting in 1936, Wegert's wife expected her husband to be detained, but it never came about. Rather, Wegert was protected by his boss, who insisted Wegert was essential to production at the Blohm & Voss factory.

Unlike Landmesser, however, Wegert avoided imprisonment and was never forced to fight for Germany. Gustav Wegert passed in 1959.

- 41,814 VOTES

1932: 'Lunch Atop a Skyscraper'

- Photo:

- Unknown author (maybe Charles Clyde Ebbets)

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

The image of 11 men sitting on a beam high above New York City - not for the faint of heart if heights are a problem - captures hard work, ingenuity, and progress during the early 1930s. To take such a picture, the photographer must have been sitting at a similar vantage point - but the details of that remain unclear.

What is known, however, is that the beam in question is part of Rockefeller Center, the men are immigrants, and the height is estimated at about 850 feet.

The picture of the men eating, smoking, laughing, and dangling their legs was featured in the October 2 edition of The New York Herald-Tribune. It's been attributed to Charles Clyde Ebbets, Thomas Kelley, William Leftwich, and Lewis Hine.

Just like the photographer itself, the names of the men have been unknown for decades. This changed during the early 2010s. After discovering a similar picture in a pub in Galway, Ireland, Seán Ó Cualáin and his brother, Eamonn, saw a note attached. It read: "This is my dad on the far right and my uncle-in-law on the far left."

They contacted the note-writer, Pat Glynn, immediately. When compared to the photo, Glynn family pictures indicate that Sonny Glynn (far right) and Matty O'Shaughnessy (far left) are both in the image.

- Photo:

- Photo:

- Arnold Genthe

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

German American photographer Arnold Genthe captured the negative effects of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, CA, within hours of it happening. To take one of his most famous photos, Genthe looked down Sacramento Street as one of the numerous fires raged in the city.

The earthquake hit at 5:13 am. For the next three or four days, San Francisco burned, with roughly 500 city blocks wiped out. The death toll from the earthquake and fires is estimated at about 3,000, with an additional 400,000 individuals left homeless.

Genthe, whose own studio was wiped out, borrowed a camera and traversed the city to document the ruins. Genthe later said of the Sacramento Street photo that it "shows, in a pictorially effective composition, the results of the earthquake, the beginning of the fire and the attitude of the people." He continued:

On the right is a house, the front of which had collapsed into the street. The occupants are sitting on chairs calmly watching the approach of the fire. Groups of people are standing in the street, motionless, gazing at the clouds of smoke. When the fire crept up close, they would just move up the block. It is hard to believe that such a scene actually occurred in the way the photograph represents it.

- Photo:

- 6829 VOTES

1972: 'The Hasanlu Lovers,' Depicting Skeletons From An Iranian Archaeology Site

The skeletons of two people who appear to be embracing each other, one with its hand on the other's face, were excavated in 1972 at the Hasanlu archaeological site in northwestern Iran. They were found in a mud, brick and stone bin with no objects other than a stone slab beneath one individual's head. Scientists do know that Hasanlu was destroyed by a terrible fire around 800 BCE, possibly from invaders, but they don't know a lot about the people who lived there at the time. The intertwined individuals might have taken refuge from the fire in the bin.

Experts have long speculated about the sex of and relationship between what are called the "Hasanlu Lovers," which were on display at the the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (AKA the Penn Museum) in the 1970s and '80s. Based on a skeletal examination, especially of each individual’s pelvis, it appears that both are male, but the one on the left also has some female characteristics. A DNA analysis found that they were both male. The skeleton on the left appears to be older, around 30 to 35 years old; the one on the right is about 19 to 22 years old.

Although they are described as "lovers," it's also possible they are a father and son (or other family members), friends, or strangers.

In a video about the Hasanlu Lovers, anthropologist Page Selinsky of the University of Pennsylvania says that "in terms of something that is emotionally evocative, it was about as good as it gets in archaeology."

- 7702 VOTES

1920: 'Power House Mechanic Working on Steam Pump' By Lewis W. Hine

- Photo:

- Lewis W. Hine

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

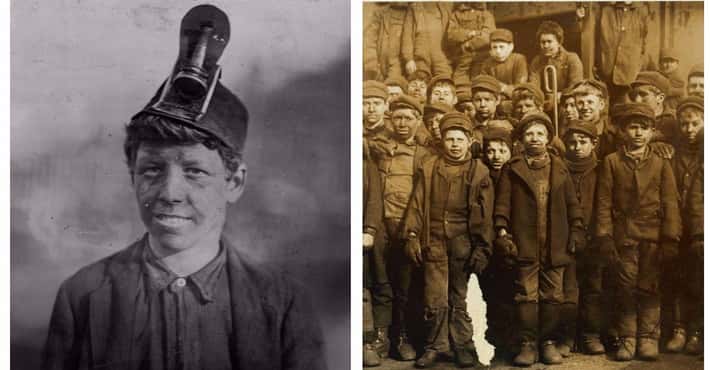

Lewis W. Hine's photographs have been credited with highlighting workplace changes, social inequities, and immigrant experiences in the United States during the early 20th century. Hine studied and taught sociology, incorporating his camera into work documenting immigrant arrivals at Ellis Island as early as 1904. He became the official photographer of the National Child Labor Committee in 1911, went to Europe with the Red Cross during WWI, and documented the building of the Empire State Building during the early 1930s.

Hine's Power House Mechanic Working on Steam Pump was taken in an unidentified location in 1920. As the muscular worker turns large bolts with his heavy wrench, the juxtaposition of massive machinery and human force takes center stage.

Hine's image is viewed as a statement about the importance of the worker himself in the face of expanding industrialization. The laborer is posed to reflect how machines define his work, but are nonetheless dependent upon him. In an increasingly mechanized environment where the worker was exploited and harmed, Hine explained, "I wanted to show the thing that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated."

- Photo:

- 81,040 VOTES

1895: Train Wreck At Monteparnasse

- Photo:

- Levy & fils

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

When the train that ran between Paris and Granville arrived at Montparnasse station on October 22, 1895, its speed was somewhere between 25 and 37 miles per hour. The high rate of speed - a choice by the conductor in the hopes of making up time - and insufficient brakes sent the locomotive through buffers on the track and, ultimately, the station itself.

Of the 131 passengers aboard the train, only four or five were injured. One person on the street was killed, newspaper vendor Marie-Augustine Aguilard, wife of the newsstand owner. She was unable to escape damage caused by the train falling 30 feet from above.

Spectators visiting the site took pictures to capture the surreal scene for posterity. There are numerous photos of the incident, many of which are attributed to one or more photographers. The picture held by the Musee d'Orsay in Paris is believed to be taken by L. Mercier.

After an investigation, the train's driver, Guillaume-Marie Pellerin, was determined to be at fault and fined. The conductor, Albert Mariette, was in the back of the train doing paperwork at the time of the incident.

- Photo:

- 9739 VOTES

1840: 'Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man' By Hippolyte Bayard

- Photo:

- Hippolyte Bayard

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

Photographer Hippolyte Bayard staged the portrait of himself as a dead man to make a point. He was an early pioneer in photography, but felt slighted by his colleagues.

Bayard invented a direct-positive process that allowed for the capture of images on paper in 1839. He displayed his photos in Paris that same year, but did not make his technique known to the public. It's believed he was encouraged to keep his method quiet by Francois Arago, a physicist and mathematician who held membership in the French Academy of Sciences and the French legislature. Bayard held off - and soon witnessed Louis Daguerre announce his comparable technique in 1839. While Daguerre went on to receive a pension from the French government for the rights to his process, Bayard earned nothing.

Bayard saw Arago's advice as a manipulation, with Daguerre (a friend of Arago) receiving international acclaim and financial stability. As a result, Bayard posed for Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man, captioning it with this text:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you. As far as I know this indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with his discovery. The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh the vagaries of human life... He has been at the morgue for several days, and no one has recognized or claimed him. Ladies and gentlemen, you'd better pass along for fear of offending your sense of smell, for as you can observe, the face and hands of the gentleman are beginning to decay.

- Photo:

- 10855 VOTES

1904: Aerial Picture Of The Pyramids By Eduard Spelterini

- Photo:

- Eduard Spelterini

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

Eduard Spelterini (born in 1852 in Switzerland as Eduard Schweizer) was known as a balloonist before he gained acclaim as a photographer. During the 1870s, he worked around the world, taking customers and patrons to new heights in his balloons.

By the 1890s, he began taking pictures from the air and selling them, becoming an innovator in aerial landscape photography. Spelterini crossed the Swiss Alps in 1898, a feat in its own right, and in November 1904 took the first photograph of the Pyramids at Giza from above.

It's estimated Spelterini was 600 meters, or nearly 2,000 feet, in the air when he took the photograph.

- Photo:

- Photo:

- Louis Daguerre

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre took this photograph from a third-story window on a spring day in Paris. In either 1838 or 1839, Daguerre captured what is believed to be the first photo of humans when he snapped the exchange between a shoe shiner and his customer, seen on the bottom left.

Daguerre's photo was possible only because both subjects stood motionless on the Boulevard du Temple for the 10 minutes it took to produce the image. The photograph, which was hugely influential in understanding how to capture light, space, and time in a photographic medium, solidified Daguerre's place as a pioneer of early photography.

Daguerre was an artist by training and trade, but had been experimenting with light capture since the 1820s. By working with chemist Nicéphore Niépce, Daguerre developed a process - appropriately called "daguerreotype" - that captured an image using a camera box, copper plates, silver iodide, mercury, and salt.

Daguerre showed his earliest photos to American inventor Samuel Morse and a friend, François Arago (a member of the French Academy of Sciences and the French legislature), but didn't go public with his process until 1839. With help from Arago, Daguerre secured funding from the French government for the rights to his technique.

- Photo:

- Photo:

- Corpus Christi Caller-Times photo from Associated Press

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

The iconic photo of Marilyn Monroe standing over a New York City subway grate looks like an impromptu snapshot. In truth, the entire scene - and resulting picture - was made possible thanks to the coordinated efforts of several individuals.

In 1954, Billy Wilder, director of The Seven Year Itch, filmed most of the movie in Hollywood. He attempted to film the subway-grate scene in New York - making it very open to the public in the process - but the noise from the grate and the crowd proved to be too much.

While Marilyn Monroe stood atop the grate, however, thousands of onlookers - at about 1 in the morning - watched as the scene was filmed 14 times. It was the film's still photographer, Sam Shaw, who took the most-famous picture.

Marilyn Monroe herself was ready for the pose, reportedly wearing "two pairs of underwear... because of the bright lights." This did not, however, "protect Ms. Monroe’s modesty quite as much as she might have liked," according to observer Jules Schulback.

- Photo:

- 13511 VOTES

Mid-19th Century: Facial Electrostimulus Experiment Photos By Guillaume Duchenne

- Photo:

- Duchenne de Boulogne

- Wikimedia Commons

- Public domain

Credited as a pioneer of modern neurology, Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne graduated from medical school in Paris in 1831. He returned to his native Boulogne, but in 1842, went back to Paris to expand his practice and research.

Duchenne sought out patients with neurological disorders, using electricity in their diagnoses and treatments. He developed a machine to administer localized neuro-electric stimuli in order to understand the relationship between muscular movement and neurological pathways.

Through the mid-19th century, Duchenne conducted numerous studies on facial muscles, documenting his work in a series of photographs. His research was published in A Treatise on Localized Electrization (1855), The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy (1862), and Physiology of Movements (1867), chronicling what he considered a "language of facial expression... [that was] universal and immutable."

Duchenne's photographs captured the expressions of several subjects, with many featuring an unnamed shoemaker. Duchenne described the man as having "a complicated anaesthetic condition of the face... an old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality, and whose facial expression was in perfect agreement with his inoffensive character and his restricted intelligence."

Duchenne's work influenced the study of muscular diseases, specifically muscular dystrophy and poliomyelitis, while uniting the growing fields of electricity, photography, and physiology.

- Photo: