Morris Day Interview: On ‘Last Call,’ Snoop, Prince & More

The incomparable singer and songwriter talks about his star-filled final solo album, dreaming big with Prince, clapping back at P-Funk, Minneapolis weather and why it’s important to be funny.

by Brad Farberman

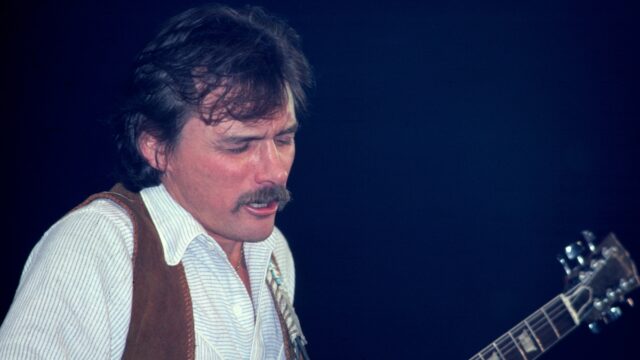

And I’m laughing, like, ‘Ah, you got me.’ ‘No, what time is it?’” Credit: Courtesy of the Artist.

On the back cover of the Time’s eponymous first album, released on Warner Bros. in 1981, six musicians are listed. But only one of them — lead vocalist Morris Day — actually appears on the LP. The rest of the sounds are supplied by producer Jamie Starr, a.k.a. Prince. And so the Time, the ecstatic Minneapolis funk group responsible for ’80s hits like “Jungle Love” and “777-9311,” was from one angle a collaboration between Day and Prince, high-school friends who had played together in a band called Grand Central, and who became pop-culture staples via the 1984 flick Purple Rain. But it was also a real band — featuring Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis before they were Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis — with Day at the helm, an operation fueled by the singer’s trademark panache and wit. Day was the heartbeat of the Time, the mischievous conscience of one of history’s premier funk acts.

The Time broke up in the middle of the decade, with Day going on to solo hits like “The Oak Tree” and the explosive “Fishnet.” But a reconciliation happened quickly, and 1990’s Pandemonium yielded the band’s biggest hit to date, “Jerk Out.” In 2001, the group entered the public eye once again with an appearance in the Kevin Smith comedy Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back. In the film, Jay, played by Jason Mewes, calls the Time “the greatest band in the world.”

In November, Day, now in his 60s and living in Las Vegas and Houston, released the sly, playful Last Call, a star-studded album featuring Time fans like Snoop Dogg, Big Daddy Kane, Flo Rida and ZZ Top’s Billy F Gibbons. On the occasion of the new LP — which Day claims is his final solo album, though he has denied he’s retiring — he spoke with TIDAL about Snoop, feuding with P-Funk, Prince’s sense of humor and much more. Day and the Time had recently received the BET Soul Train Legend Award, and the singer was delightfully generous and charismatic in conversation. What time is it?

How did you meet Billy F Gibbons? And how did that track come about?

My manager, Courtney Benson, was hanging out at the Polo Lounge in L.A. Famous Hollywood hotspot. And Billy happened to be there. Somehow they struck up a quick conversation, and [Courtney] ended up mentioning that he repped me. And Billy jumped up and did the Chili Sauce across the floor. And he’s like, “I love Morris!” So Courtney was like, “It would be cool if you guys could do something together.” And the next thing I know, we was in the studio, man. [laughs]

The collaboration made a lot of sense to me. I can almost hear you singing some of his songs, like “Sharp Dressed Man.”

You know what? Hey, man, that’s a great idea. Go in and remake some of them, and throw a verse in there. That might be cool, man.

I also wanted to talk about “Use to Be the Playa,” with Snoop. Did he say that the Time had been influential to West Coast hip-hop in the ’90s?

Years back, me and the original fellas — Terry, Jimmy, Jellybean [Johnson] — we all were putting a project together and we wanted to put Snoop on at that time. It never happened, but we had him on the phone, and Snoop was like, “Hey, man, I’ve always been the eighth member of the Time.” He’s just always been into it, you know?

Another legendary MC, 2Pac, sampled “777-9311,” which is heralded today as having one of the greatest drum machine beats of all time. Do you remember what you thought when you first heard that beat?

Now mind you, I’ve always been a big Tower of Power fan. … When Lenny [Williams] got in the band, to me, Back to Oakland and all of that stuff was just some of the greatest music I thought I had ever heard. Dave Garibaldi, the drummer, was always my favorite, or one of my favorites. I heard that he had programmed for LinnDrum, and that he had programmed that beat. I took to that beat right away. And so we used some of that beat, and added to it ourselves.

Were you surprised by the resurgence of “Jungle Love” after Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back? How did that happen?

So that was cool, because the Time had always been, at that juncture, a “grown-up band,” so to speak. Because all of our fans were now in their 40s and maybe even 50s at that point. And Kevin Smith comes along. He took a chance, because he told me he had already written us into the script before he even contacted me. Of course we were happy to do it. At the time, two of my sons were in grade school or middle school, so I went from being their dads to being, “Hey, that’s Morris Day!” [laughs] It definitely introduced us to a younger audience.

Tell me about the origin of the name the Time. Originally there was the band Flyte Tyme, and then eventually it turned into the Time.

To my knowledge, Flyte Tyme was never considered to be a part of how the name came about. And Flyte Tyme always spelled Tyme t-y-m-e. At first, Prince wanted to name the group the Nerve. Now mind you, this group was being put together back when the Cure, and the Fixx, or whatever; those kind of groups were out around then, in the early ’80s. He was trying to tap into some of that. Then he wanted to come up with a phrase that was spoken every day. The Time popped to mind, so he wanted to name it the Time. I was like, “I like that.” So then, “What time is it?” That phrase, that name, is mentioned by just pretty much everybody, every day. [laughs] So there was some cleverness to that. And even to the degree where people come up to me in an honest moment — don’t know who the hell I am — and ask me, “What time is it?” And I’m laughing, like, “Ah, you got me.” “No, what time is it?”

When the band started, what music had you been listening to around that time? What were the reference points when the music started to come together?

I was heavy Funkadelic. I was heavy Ohio Players. And Cameo. And a lot of the funk groups that had come out in the ’70s, mid-to-late ’70s. The funky Kool & the Gang — not the “Joanna” Kool & the Gang — but the “Jungle Boogie,” “Funky Stuff,” all of that. That Kool & the Gang I was into a lot. I like Kool & the Gang and their pop renditions, but they used to be more of a funk band, and I really used to listen to them a lot back then. Of course I was listening to Tower of Power. I listened to a lot of heavy fusion music. The Billy Cobham Mahavishnu Orchestra, Lenny White, bands like that. I liked Frank Zappa because he infused a lot of fusion music into a rock-fusion thing, and that was really cool. It was kind of diverse, but heavily musical. I was listening to deep stuff.

You mentioned Billy Cobham. Can you talk about your drumming influences? You started out with Prince as a drummer, in Grand Central.

Like I said, I liked Dave Garibaldi a lot. I liked the drummers from Parliament-Funkadelic and a lot of those guys. But to a deeper level, I always liked the fusion and a lot of the changes. We did a lighter version of that kind of stuff with the Time. We used to go heavy in concert; we had some real heavy arrangements that were a lot more fusion-oriented. Billy Cobham — I loved his drumming. I never tried to drum like him because he was so powerful that he just kind of overpowered the drums. [laughs] But I loved all of that fusion music back then.

Can you remember first hearing the echoes of your music in other people’s music, after the Time had become popular?

It’s funny — we were busy trying to defend our own sound. It’s pretty crazy that I got to know all of the people that were my heroes on vinyl, that I thought were magic. Now I know George Clinton, and I know Bootsy Collins, and I know Kool, from Kool & the Gang. All those guys that I idolized, I know them. Some people were saying we were copying their sound. [laughs] I think it was either George Clinton or Bootsy, one of them, that said, “Meow, meow, Morris the Copycat,” indicating that we bit, maybe, some of their sounds. [Ed. note: Day is paraphrasing lyrics from the 1983 P-Funk All-Stars track “Copy Cat,” produced by and featuring Clinton and Collins.]

But I didn’t hear that. Early on we were defending our own originality, as opposed to listening for other people biting our sound. We went right into the studio and did a rebuttal, too. That’s when we did “Tricky.” Listen to the other side of [the “Ice Cream Castles” single], and it starts off, “Why you big, tossed-salad hairdo having …” We were throwing a direct hit back at George Clinton and Bootsy Collins at that point.

In the ’80s, these great synthesizer riffs and lines were so important to all this music. Was that part of the conversation when you were playing and recording, that we need to have these synth lines?

We had a compact band, Grand Central, the band that I played in with Prince. Flyte Tyme, on the other hand, had a really big band. And there were a few other bands around town that had horns and all of that stuff. We never had that. So we started to use the synthesizer to make the horn lines. That’s kind of how that was born, and it just kept progressing. And now, when people mention the Minneapolis Sound, that’s one of the key elements of the Minneapolis Sound, the synth-driven lines instead of horn-driven lines.

How do you feel like Minneapolis informed all of your music? Could this music have come from anywhere else?

I think there were some key elements about Minneapolis which makes it exclusive to what happened and the way the Minneapolis Sound was formed. The weather was one. When you have six months of intense weather, you don’t want to be outside. I feel like if I had come up in California — which, by the way, is where I wanted to grow up, but somehow that didn’t happen — if I had been outside, running the streets all the time, I’m just not sure that it would’ve come out the same way. So you have that. You’re stuck in the cold. We rehearse all the time. After everybody was done with school or whatever their daily activities were, we were in the basement and we were woodshedding and we were rehearsing. Every day.

There’s that, and then there’s the radio. There weren’t really any urban R&B stations. There was one AM radio station called KUXL that broadcasted from basically sunup to sundown. And AM, so it had probably a one-mile radius before you start losing the signal. And that was that. So we listened to a lot of pop music. We listened to the Black artists that were able to surface — your Lou Rawls, your Diana Ross, Ohio Players, Earth, Wind & Fire and stuff like that that was starting to surface on pop radio. But then a lot of pop songs — your Neil Diamond — and then your rock. We just heard it all, and I liked a lot of those songs.

I would have to go to the mom-and-pop stores to get the underground funk records that weren’t getting played on the radio. So we had these elements: We’re listening to these strong pop hooks all day long on the radio if we tuned in, and then we’re listening to these heavy funk grooves, and then we’re listening to fusion. We’re inside woodshedding, and there were a lot of budding musicians in Minneapolis. It seemed like there was a band every couple of blocks, so there was strong competition as well. Just a lot of elements that I feel were pretty exclusive to a city like Minneapolis.

When you and Prince were kids just trying to figure out how to play music together, do you remember what those conversations were like — your goals, or pointers you would give to each other?

Well, you know, Brad, I always like to say that “it’s in the book.” But it is in the book — On Time: A Princely Life in Funk by Morris Day and David Ritz. But anyway, yes, man, when I got in their band, they changed my outlook on my life, on my music and everything, because I always thought it would be nice to be a recording artist, you know? I used to flirt with the idea: “What if I could get in that box?” — meaning the TV.

But when I met these guys and started hanging out with them, they never said, “If I make it in the music business.” Our conversation was “when I make it”: “When I make it in this business, I’m gonna get me a Corniche.” And that’s how I started talking and thinking, and it just changed my outlook.

Can you talk a little bit about the importance of including humor in your work?

I was an obnoxious teenager. And in my early 20s, you know, obnoxious. Laugh loud. Talked a lot of shit. We would do stuff like that and Prince, as mysterious as he presented himself, he was quite the prankster and jokester. He was a funny guy, you know? We laughed a lot, man, at a lot of stuff. And so we would be recording, and we would be doing or talking some crazy shit, and we would be like, “We gotta put that on the record.” We just started doing that, and people loved the personality of it and that we took it to that level and made it feel like You’re a part of it. You can laugh at this. Sometimes you hear a great song and you hear the verse, you hear the hook. Verse, hook, bridge, whatever. It’s a great song. We made songs that were great, but they were also fun and had personality to them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read more about the Time’s classic 1982 album What Time Is It?