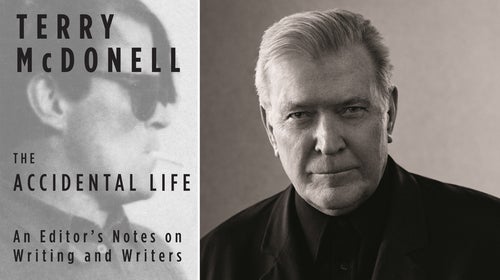

Terry McDonell’s new book, The Accidental Life, uses a short-essay format—there are 78 pieces in all—to convey the ups, downs, glamour, fun, excitement, and miseries of a magazine journalism career that has involved stops (often on top of the masthead) at publications that include San Francisco Magazine, Rocky Mountain Magazine, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, Manhattan, Inc., Smart (which he founded), Esquire, Sports Afield, Men’s Journal, Us Weekly, and Sports Illustrated.

Oh, and there was also Outside, where McDonell put his imprint on the then-new publication as an editor starting in 1977. The history of Outside during those years is complicated, and it’s braided with that of Mariah, a startup that appeared first and had a bold new aim: to capture the tremendous surge of interest in outdoor sports, adventure, and exotic travel that was happening among Baby Boomers as they moved into their twenties and thirties. Mariah debuted in February 1976 with a column by owner Lawrence J. Burke. “Mariah,” he wrote, “is dedicated to the spirit of any person who is sensitive to the beauty and freedom nature offers.”

The earliest version of what became Outside appeared as a section called “Let’s Go Outdoors,” published in the June 3, 1976, issue of Rolling Stone. Outside itself appeared as a Rolling Stone magazine-inside-a-magazine later that year, and McDonell came on as a senior editor under managing editor Will Hearst. Outside regular Tim Cahill once told an interviewer that, during the Rolling Stone era, “[T]he person whose personality [was] really stamped on the magazine … [was] Terry’s.”

Rolling Stone owner Jann Wenner sold Outside to Mariah Media in late 1978, by which time McDonell had moved on to continue with a career that saw him collaborate with some of the most prominent names in modern American fiction and nonfiction, including Jim Harrison, Edward Abbey, Peter Matthiessen, Thomas McGuane, P.J. O’Rourke, Hunter Thompson, George Plimpton, James Salter, and Richard Ford. Here, he talks with Outside editorial director Alex Heard about his four-decade adventure in journalism.

OUTSIDE: There’s a great story in your book about what it was like working with Jim Harrison, who could be a little touchy about having his words rearranged. You write: “I learned to tread lightly or risk being told, as I once was by him, ‘You lynched my baby.’ ” What was it like to deal with someone who took as much pride in his words as he did, and was combative if he decided you went too far?

MCDONELL: Jim thought of himself as a poet, which he was before he was a novelist and way before he did any journalism. And no one edits poetry, you just don’t do it.

His thinking was that he had worked everything out ahead of time, before he wrote. And then he wrote, and he was done. He did very little revising and was very proud of that, and was not at all interested in the back-and-forth editing process that most editors tried to put him through.

This was all done with good humor, and he would be reasonable if you pointed out that he used the same word twice in the same paragraph. Or he might say, “I did that on purpose.” I learned very early to take him seriously, because it was never clear when you read the story what was the most important three-word phrase in it. But I knew after working with him a short time that he had these absolute darlings and he was not going to let you mess with them, for sure.

In the Outside library, I found an old Newsweek cover story from the summer of 1977 headlined “Life Outdoors.” The cover shot shows two men, two women, four external-frame backpacks, moustaches, perms, short-shorts, the whole mid-seventies deal. Newsweek had noticed the surge of interest in the outdoors, and they mentioned the launch of Mariah. For somebody who’s young right now, it’s automatic that magazines like Outside have always been around. You were there when that leap happened—when people saw the demographics and the trends and where they could go.

The thing we always said about Rolling Stone was that it was about a lot more than the music. So we had variations on that—Outside was about a lot more than the Sierra Club and nice camping trips, or anything we saw to be kind of square and soft.

At the same time, what we knew—and what I was a fan of at that time—was Mariah. Larry Burke had conceived of it from his own experience traveling around the world, so it had an adventure travel kick to it before there was any such thing as adventure travel as a defining idea. Mariah hinted at expat-ism and everything that’s a little bit dangerous, a little more fun, and it covered going to very far-out, deep places. Outside was going to be about that, too, from the beginning. But Outside also had an environmental-news edge to it. We were very interested in covering the radical environmental movement particularly. And we wanted to be literary at the same time. So I went after Ed Abbey, who of course had written The Monkey Wrench Gang, which was about blowing up a big dam to free rivers.

You invited Abbey to write for Outside starting in 1977, with a postcard that generated a collect call by him from Utah.

Yes. I sent him a postcard, and he did call me back collect, and I said I had some ideas for him, but if he had any ideas himself, Outside was wide open to anything he might like to write. He said, “Well, I certainly don’t need another editor, but I suppose I could use the money.” He said he wanted to go to this island off Baja California. So we paid for a chartered plane for him to fly there, and the headline was something like “Desert Island Solitaire.” It was classic Ed Abbey stuff, and a perfect piece for Outside.

Of our two leading presidential candidates this year, which one do you think Abbey would dislike the least?

He would have hated Trump, because Trump is such a bully. Ed had a real firm grip on fairness. Anything that he saw that looked like anybody bullying anybody else would really piss him off. And that’s what he thought the BLM and Forest Service were doing—and that the government was a bully. He would use that word.

I also found a master’s thesis written in 1982 called “Natural Selection: the Evolution of Outside Magazine,” which describes the parallel origins of Mariah and Outside. There’s a story about your interview with Jann Wenner for an editing job. It says: “McDonell mentioned that he would like to get the magazine a few minutes on CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. ‘It’s not going to be that kind of magazine,’ said Wenner. ‘I’ll make it that kind of magazine,’ answered McDonell.”

So you knew right off that Outside would be home to serious reporting, as well as outdoor how-to, travel, and entertainment?

Yeah, and when I said that to Jann, I meant we could break news. No one was covering the environmental movement from the inside, like I knew we could, like the way Rolling Stone had done with politics. We wanted to be literary at the same time. What could be more interesting than that combination?

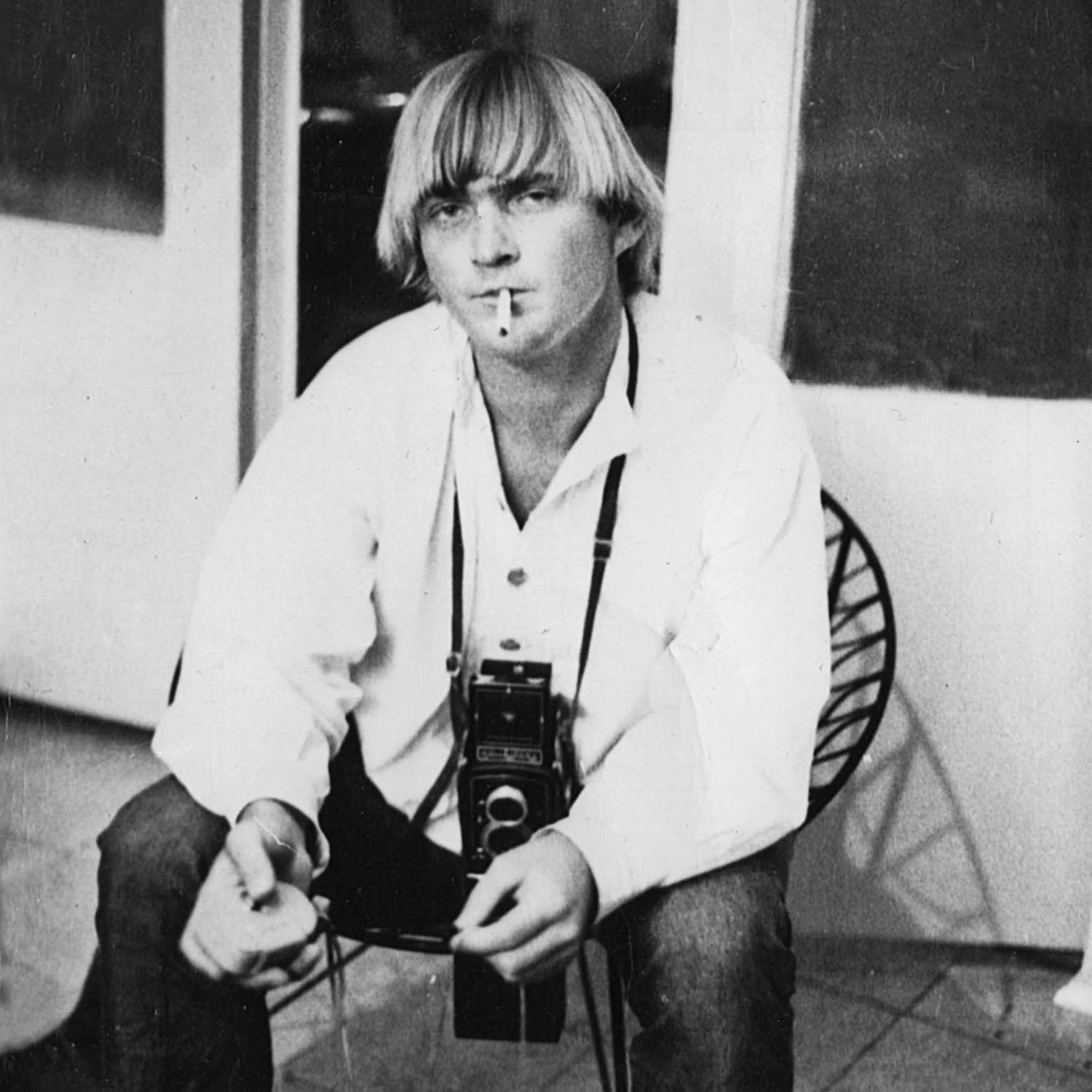

And we did get on Walter Cronkite. The article that made it happen was a story we ran on Nanda Devi, which was about how climbers had placed a listening device high on the mountain for the CIA. Galen Rowell brought that in. He was an extremely accomplished climber, also a brilliant photographer, and he knew everybody in the climbing community, so he had known about that for a while. We convinced him to tell it.

No one was covering the environmental movement from the inside, like I knew we could. We wanted to be literary at the same time. What could be more interesting than that combination?

Looking through old issues, and thinking about writers who were influential in creating the voice and style of the magazine, Tim Cahill obviously comes up. I think many people now associate him mainly with adventure-travel romps, and maybe they don’t know what a great reporter he was. For example, he had done a Rolling Stone story on Jim Jones and Guyana.

He did that story. He also went down the coast of Mexico and found a place that was pretending to be a research and incubation laboratory for turtles, but they were actually just killing the turtles. It was a scam to get grant money and a kind of turtle genocide on the beach. That was another story that Outside broke.

You mention the influence of a writer I wasn’t aware of: Robert F. Jones, a Sports Illustrated regular who wrote a novel called Blood Sport: A Journey up the Hassayampa. In your book you say, “I never told Bob, but that novel informed almost everything we did during the start-up of Outside.” What was it about his work?

Bob Jones was a great journalist, a correspondent for Time, but he got tired of Time and moved to Sports Illustrated, where he covered some NFL, some car racing, and all things outdoors—and he spent a lot of time in Africa. He loved hunting, fishing, exploring, and especially, wild-ass travel. When he stopped being a journalist full-time, he did so to write literary novels that he’d been thinking about all along. The first one was Blood Sport, the story of a kid who goes up a mythical river on a quest through a magical landscape roamed by all kinds of strange fauna mixed together—saber-tooth tigers, and giant marlin in the river, beautiful prehistoric birds, albino monkeys, buffalo. And the kid rides really hot dirt bikes, and is a great shot with really cool shotguns, and is good on horses and in a canoe, and he cares about the environment at the same time. Perfect. All things that were part of the culture we were covering then. The novel layered all of it on: an environmental consciousness, adventure, travel, and pushing it to get as far out there as you could. It was a kind of literary hallucination about what Outside was about for me.

Some of the writers who come up in The Accidental Life appear more than once, giving the sense of a narrative thread. For example: Hunter S. Thompson and George Plimpton. There’s a great scene in which you play acid-fueled golf with both of them in Colorado. Then the next day, at Thompson’s house, Walter Isaacson and Douglas Brinkley both turn up, wanting to interview Thompson. That’s a lot going on. When you were living an experience like that, did it almost seem out-of-body?

We were unhappy to see those two guys. George and I went out there to interview Hunter together—it was going to be the first journalist entry in The Paris Review’s series on writers at work. And I was starting Smart magazine and I wanted Hunter to write for our first issue. So that was our deal.

We went out there, we played acid golf—though George only drank scotch—I went to bed early, they stayed up all night. The next afternoon, about five o’clock, we finally got to the interview.

Hunter always liked to have audiences, and the more distractions, the better. It made him able to go through all the questions like a broken field runner showing off his dexterity. So he would invite local friends over, and he called Walter, who was visiting Aspen at the time, and Doug, who later edited a collection of Hunter's letters.

George was frustrated by this, but he led this interview and it went on for a long time because of all the interruptions. Everyone had their own questions. Then it didn’t run for a number of years, but when it did it was wonderful, smart, and hilarious at the same time. One of the reasons Hunter and George got along so well is that they were both big-time pranksters, and they loved combining rollicking good times with whatever serious business was at hand.

When I read about people’s encounters with Thompson, he always seems to be in the same character that you get on the page. Was that inseparable from the real person, or did he sometimes drop it and say ordinary things like, “Hey, Terry, my back hurts. Any recommendations on what I can do to get some relief?”

Of course he did. The surprising thing about his persona was that, sometimes when it cooled down a little bit, he could be almost courtly. He had wonderful manners when he wanted to use them, and he could be absolutely charming, especially to women. He made you feel like you were the center of his world.

Your pieces about Plimpton are great. As you mention, he had signed a contract to write his autobiography not long before he died, and that book never got written. He had also made it clear to you that he was ambivalent about doing it. If he had lived ten more years, do you think he would have produced it?

I don’t know, and I’ve thought about it. I think he had so much pride as a writer, that if he started, he probably would have gotten into it and it would have been a great thing. But he didn’t want to make that first start. To him, it felt like it was the end of something, like he was stopping.

Another thing that comes through in the book is your love of the accouterments of magazine-making—for example, there’s a nice section on light tables, which editors and art directors used to use to look at slides together. We’re in a period of major transition now, and some aspects of print magazines have disappeared—as have many magazines, for that matter. What do you think the print-online endgame looks like?

I think the upheaval is going to accelerate. The shakeout is going to continue to be about the quality—to use an overused word—of content, both online and in print. When you look at the research, you see how much people still like the physical characteristics of a magazine or a book. That’s especially true for magazines in fashion and upscale titles, with beautiful graphics as well as fine writing and reporting. Even as the online universe continues to expand, it doesn’t necessarily have to kill print magazines. That balance will have to be found, but what’s going to determine who wins and loses is how good that content is.

If you were coming out of college now, would you want to work for a print publication? Or would go straight to the online side?

I was drawn to the language and the writing and the journalism. That’s where I found my first satisfaction. The arc of my career goes from the cresting of the New Journalism wave all the way to now, when we have classes in which journalism is taught as an engineering problem. I like all of that. The key is that the journalism has got to be solid and true on whatever platform you’re using, and if you can put it out on many platforms for different people to use in different ways, all the better.

Alex Heard (@alexheard) is the editorial director of Outside. Read an excerpt from The Accidental Life here.