Peer Reviewed

Misinformation perceived as a bigger informational threat than negativity: A cross-country survey on challenges of the news environment

Article Metrics

CrossRef Citations

Altmetric Score

PDF Downloads

Page Views

This study integrates research on negativity bias and misinformation, as a comparison of how systematic (negativity) and incidental (misinformation) challenges to the news are perceived differently by audiences. Through a cross-country survey, we found that both challenges are perceived as highly salient and disruptive. Despite negativity bias in the news possibly being a more widespread phenomenon, respondents across the surveyed countries perceive misinformation as a relatively bigger threat, even in countries where negativity is estimated to be more prevalent. In conclusion, the optimism of recent research about people’s limited misinformation exposure does not seem to be reflected in audiences’ threat perceptions.

Research Questions

- RQ1: How salient do people perceive negativity and misinformation to be in the news environment?

- RQ2: How do people perceive the severity of the threat of negativity and misinformation in the news on society and audiences’ worldview?

- RQ3: To what extent are the salience and threat of negativity and misinformation in the news perceived differently across countries?

Research Note Summary

- A cross-country survey across diverse democracies (the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Poland, and India) was conducted to offer a comprehensive overview of how news audiences perceive the quality of their news environment with respect to the prevalence and impact of misinformation and negativity bias.

- The findings indicate an overall cynical perception of the news: Both negativity and misinformation are on average perceived to prevail in more than half of all news and associated with a disruptive impact on society.

- While the negativity bias is arguably a more systematic and widespread phenomenon in the news, it is primarily misinformation that alarms audiences across the surveyed countries. Even when negativity is estimated to be more salient, misinformation is seen as the most disruptive threat.

- While misinformation is seen as more threatening than negative news in the majority of countries, we found different perceptional gaps regarding their estimated salience across the countries. These gaps correspond to contextual differences in misinformation resilience.

- We suggest stakeholders should focus their interventions on cultivating more accurate and optimistic perceptions about news and news production to re-establish trust in the news media, rather than constantly warning audiences of the potential for deception.

Implications

How audiences evaluate their news environment is essential for their access to perceived quality information and, more generally, for a well-informed citizenry (Van Aelst et al., 2017). This study brings together two intertwined challenges that can undermine the (perceived) quality and trustworthiness of news, namely perceptions of negativity—i.e., focus on negative rather than positive events—and misinformation—i.e., information that is false or deceptive—in the news. First, the disproportionate focus on negativity is an engrained systematic bias of journalistic processes and is linked to distorted worldviews (Soroka & McAdams, 2015). Second, misinformation is currently viewed as an omnipresent societal threat, disrupting audiences’ news diets (Pennycook et al., 2021). Given their attention-grabbing, conflict-oriented, and persuasive nature (Trussler & Soroka, 2014; Tsfati et al., 2020), both negativity and misinformation can mislead audiences and challenge credibility ratings of news (Soroka et al., 2019).

Despite their inherent link with today’s news ecology and trends toward declining media trust, little research has attempted to simultaneously study negativity bias and misinformation. The main contribution of this study lies in understanding audiences’ perceptions of two key informational threats within an overly complex news environment characterized by a multitude of challenges regarding how to inform oneself to come to an accurate worldview. Because media bias and misinformation are sometimes converged into a single phenomenon by audiences (Kyriakidou et al., 2023; Osman et al., 2022), exploring whether people perceive a difference in the salience and threat levels of both challenges when addressed separately will provide a novel and comprehensive understanding of how media users make sense of the quality of today’s news environment. Even more so, given that extant research on perceptions of misinformation has mainly looked at the perceived salience or dimensions of the threat (Newman et al., 2023), the explicit distinction between perceived prevalence and impact made in this paper enables us to better understand how to reconcile the discrepancy between the estimated threats of problematic information versus the low amount of misinformation and related informational disorders found in recent studies (e.g., Acerbi et al., 2022).

An extensive body of literature has documented how news media are characterized by systematic biases in terms of disproportionate attention to negativity (e.g., Esser et al., 2016; Soroka & McAdams, 2015; van der Meer et al., 2019). This negativity bias has been associated with a core news value and journalistic tools like dramatizing or sensationalizing used to garnish attention in a competitive attention economy (Harcup & O’Neill, 2017). This systematic bias is not without consequences, as it can present an overly negative media reality which creates worldviews amongst audiences that do not accurately reflect reality (Jacobs et al., 2018; van der Meer et al., 2019). Accordingly, this negativity bias tends to be associated with lower news quality.

In this paper, we define misinformation as an overarching term to denote information that is false, inaccurate, deceptive, or not based on relevant expert knowledge (Vraga et al., 2020). Here, we acknowledge that false information can both be driven by honest mistakes and intentional or planned deception (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). Despite the potential far-reaching consequences of misinformation, recent research has shown how the amount of misinformation in audiences’ media diets is relatively little, often even below one percent (Acerbi et al., 2022; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2020; Osmundsen et al., 2021). Yet, the constant attention to this phenomenon, both in media and public debate, can distort people’s evaluations of their overall news environment (van der Meer et al., 2023). Despite its low prevalence, audiences may perceive that misinformation affects the quality of their news environment and significantly threatens societies.

Although both challenges indicate a low evaluation of news quality, the negativity bias could be understood as a more systematic threat to the news ecology, while misinformation is a more incidental risk. On the one hand, literature has documented a long history of negativity being a consistent and systematic bias in news production and news effects (Soroka, 2006; van der Meer et al., 2019). On the other hand, misinformation has more recently raised ample concern of more incidental spread of falsehoods that, for example, are (accidentally) picked up by news outlets (Tsfati et al., 2020). For that reason, it could be argued that the level of negativity should be more a structural disruptive issue for news quality than incidental misinformation exposure. However, as risk assessments are generally not based on systematic and rational reasoning (Rittichainuwat et al., 2018), it is important to explore how audiences perceive these distinct yet interlinked challenges to news.

In line with a growing body of literature that has approached the perceptual components of information disorders (Knuutila et al., 2022), this paper looks at the perceived salience—i.e., audiences’ estimation of the prevalence of the informational threats in the news environment—as well as threat perceptions—i.e., audiences’ perceived risk for society of the informational threats—of negativity and misinformation. Measuring both concepts together will provide a novel and detailed account of audiences’ overall assessment of their information climate. For example, although media users may perceive that negativity or misinformation is prevalent, they may not always consider their impact to be both harmful and disruptive. Negativity, as a more systematic news bias (Soroka & McAdams, 2015), could be perceived as more salient compared to misinformation, which makes up only a small part of audiences’ news exposure (Acerbi et al., 2022), while misinformation is still seen as a more substantial threat to societies.

This study relies on data from multiple countries (i.e., the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Poland, and India). Arguably, the question of whether concerns about negative news and misinformation are proportionate to the threat is context-dependent. Differences in country-level factors such as the strength of democracy, press freedom, or type of media system (Humprecht et al., 2020; Knuutila et al., 2022) can potentially play an important role. For example, in cases where press freedom is low and polarization high (e.g., India), concerns about misinformation and negativity may be more valid than in cases where the press can act independently from any external pressures while polarization is relatively low (e.g., the Netherlands). Countries’ varying levels of vulnerability to misinformation are also stressed in the resilience framework to misinformation (Humprecht et al., 2020). Specifically, in more polarized and distrusting contexts, such as the United States and India, news users may perceive the threat of misinformation to be more severe than in countries where the media is trusted most of the time (i.e., Germany and the Netherlands).

Our survey results provide insights into how misinformation is understood by audiences in comparison to negativity as another challenge to the information climate. Even though negativity in the news could be seen as a more structural bias, misinformation is estimated to be similarly present. On average, both negativity and misinformation are estimated to be prevailing in more than half of all news. These high levels of perceived salience indicate an overall cynical evaluation that people hold of the news. When looking at the individual countries, negativity is estimated as relatively more prevalent in the Western European countries, while in the United States and India misinformation is estimated to be more salient. Citizens from countries faced with political divides and challenges regarding press freedom consider misinformation more engrained in the news than a negativity bias. This finding corresponds with the lower level of resilience to misinformation in contexts of high media distrust, strong polarization, and low press freedom (Humprecht et al., 2020). In India and the United States, a high degree of polarization and low trust in established media (e.g., Newman et al., 2023) should offer a more vulnerable context for misinformation—which corresponds with the higher perceived prevalence of this issue in these countries. As attacks on the free press and journalism are prevalent in the United States and India, the weaponization of mis- and disinformation may also correspond with a higher perceived threat of misinformation (Egelhofer & Lecheler, 2019).

Yet, when we look at the perceived disruptive potential, misinformation is considered more threatening to the news environment than negativity. So even though negativity is, for some countries, estimated to be more salient in the news, misinformation is still seen as a bigger threat. In all countries but India, people are substantially more alarmed by the disruptive character of misinformation than of negativity, even in those countries that estimated negativity as more salient in the news. While recent research is more optimistic about how much people get exposed to misinformation (Acerbi et al., 2022), this does not seem to resonate with people’s threat perceptions. Potentially, the prominent discourse on misinformation amongst elites (Van Duyn & Collier, 2019), well-intended alarming messages about the disruptive potential of misinformation (van der Meer et al., 2023), and several high-profile cases that highlighted the potential threat of misinformation (e.g., the storming of the U.S. Capitol in 2021), make people more concerned with misinformation, even to disproportionate levels. Hence, the constant references to “flooding” amounts of misinformation by media and political actors might misinform risk perceptions in public opinion, potentially even resulting in moral panics surrounding misinformation (Jungherr & Schroeder, 2021). These findings might indicate that deception rather than truth is the default route of information processing. The truth-default theory states that individuals, by default, are more likely to accept new information’s honesty than to doubt its truth value (Levine, 2014). Yet, similar to other recent empirical findings (Luo et al., 2022; van der Meer et al., 2023), respondents in our surveys seem to be aware of the threat of being exposed to a distorted media reality rather than perceiving most news as inherently honest.

Our findings have different real-world implications for citizens, journalists and media practice, as well as policymakers. While negativity might be a more structural and prevalent phenomenon, interventions should focus on increasing news users’ understanding of news production and how it can show biased reality (van der Meer & Hameleers, 2022). At the same time, media can explore the usage of constructive journalism to highlight more thematic trends and societal progression (Hermans & Gyldensted, 2019). Since heightened misinformation perceptions might not reflect actual exposure, information literacy programs should focus on improving the accuracy of risk perceptions (Acerbi et al., 2022). In line with Acerbi et al. (2022), we argue that policymakers and educators should dedicate their interventions to increasing trust in reliable news sources rather than reiterating the potential threats to the news environment, a threat we observed to be already well-known to audiences. In designing such interventions, inspiration can be taken from existing interventions, e.g., Pennycook et al., 2021; Tully et al., 2020. Furthermore, it may be important to differentiate between lower- and higher-risk contexts of misinformation and negativity to ensure that audiences can arrive at more accurate perceptions of threats in their national news environment (see also Knuutila et al., 2022).

Findings

Finding 1: High perceived prevalence and threat of negativity and misinformation in news.

Answering RQ1, the findings from the survey indicate that respondents across different countries estimate that a high percentage of the news is negative (M = 53.24, SD = 24.85) and contains misinformation (M = 53.29, SD = 21.11), indicating that respondents estimate that the majority of news is negative and contains misinformation. A paired-samples t-test (mean difference = .02, df = 2643, t = 0.03, ns) showed no difference in mean estimation between negativity and misinformation.

RQ2 asked about the perceived threat of negativity and misinformation in the news. Comparable to the estimation of salience, the perceived threat of negativity (M = 4.67, SD = 1.38) and misinformation (M = 5.33, SD = 1.36) were estimated to be on the higher end of the 7-point scale. Yet, a paired-samples t-test (mean difference = .67, df = 2628, t = 22.39, p < .001) showed that respondents estimated the threat of misinformation significantly higher than that of negativity.

Finding 2: News users in the majority of the included countries perceive misinformation as a bigger threat than negativity, while the perceptions of their salience vary across the countries.

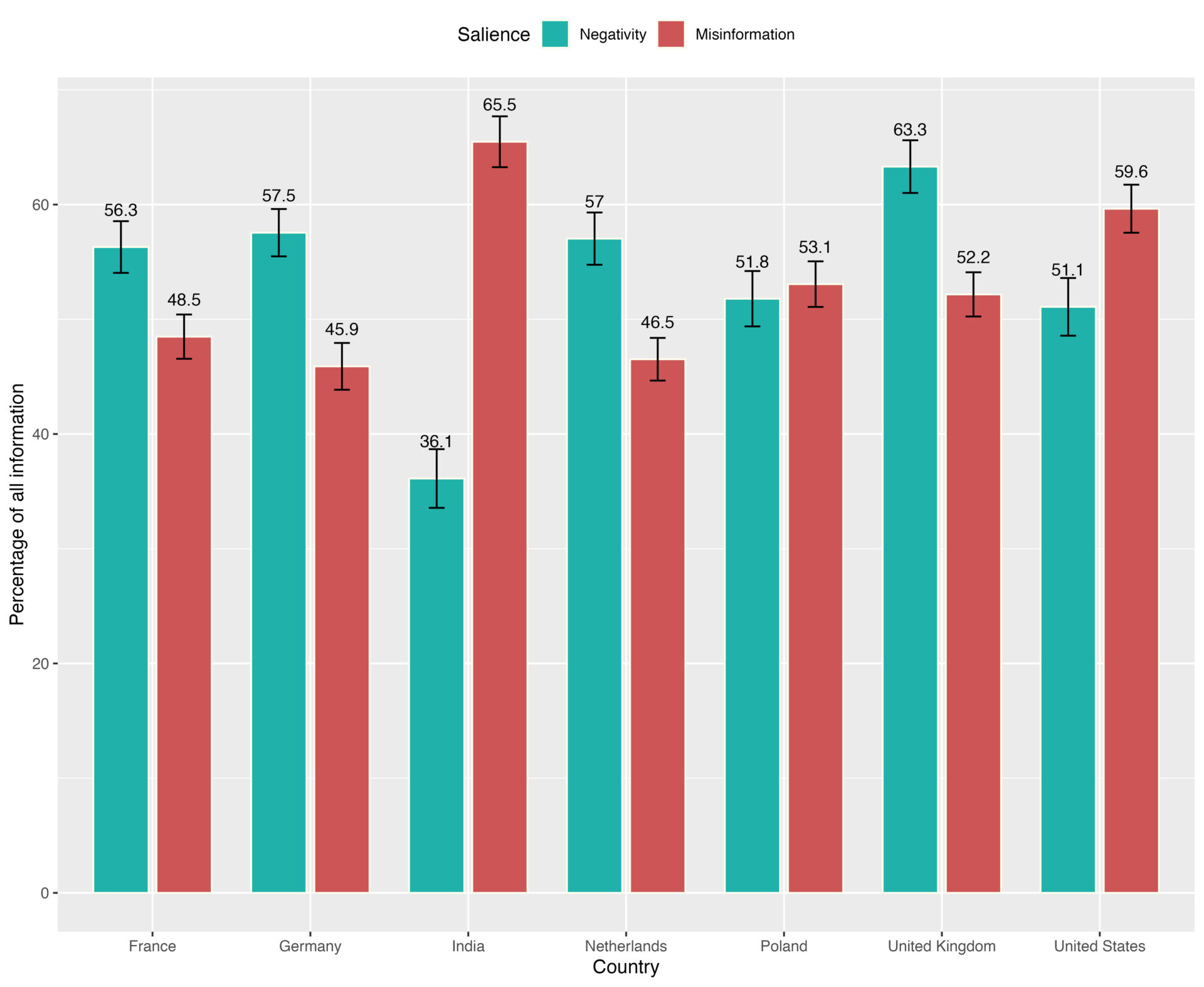

For RQ3, we explore country differences. Figure 1 presents the estimated percentages of negativity and misinformation in the news across the seven countries in the survey. A pattern of similarities can be found for the Western European countries (the Netherlands, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom). Here, negativity (ranging from 56.3% to 63.3%) is estimated to be significantly more prevalent than misinformation (ranging from 45.9% to 52.2%). In contrast, in the United States and India, misinformation (59.6%; 65.5%) is estimated to make up a more significant proportion of the news than negativity (36.1%; 51.1%). Finally, in Poland, no significant difference was observed between the estimation of both. In line with the theoretical expectation that some more polarized and populist settings offer stronger discursive opportunities for disinformation (Humprecht et al., 2020), we observe that perceived misinformation levels are highest in polarized contexts such as the United States and India. Comparable to other research exemplifying the large issues with mis- and disinformation on social media in India (Neyazi et al., 2021), we see that respondents from India are most concerned with the salience of misinformation. In the most resilient contexts included in our study—the Netherlands, France, and Germany—misinformation perceptions are relatively lower but still above 45%.

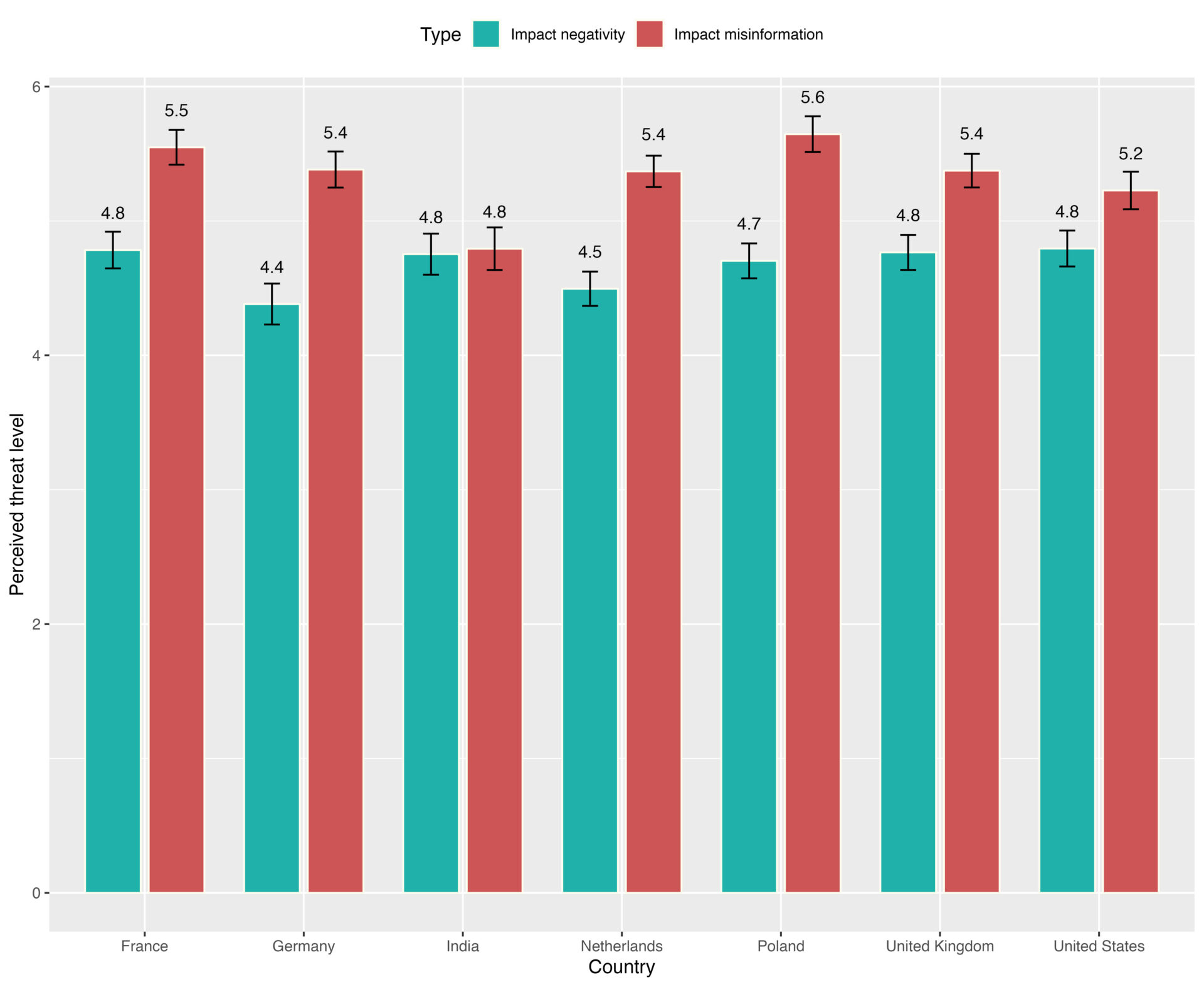

A different picture arises in Figure 2 that depicts the perceived threat of negativity and misinformation. Except for India, respondents from all countries in the survey perceived misinformation as a significantly larger threat than negativity. For these countries, misinformation was perceived as highly threatening (scores from 5.2 to 5.6 on a 7-point scale). The threat of negativity was significantly lower but also scored above the mid-point in all countries (4.4 to 4.8).

Methods

A cross-country survey (N = 2,979) was fielded in seven countries: the United States (545), the United Kingdom (411), the Netherlands (393), Germany (394), France (389), Poland (408), and India (439). The main rationale for focusing on these different countries was based on research indicating that the misinformation perceptions depend on the national context (e.g., Newman et al., 2023). Based on various country-level factors, such as press freedom, polarization, the resonance of populist ideology, and the delegitimization of the press (Humprecht et al., 2020), it can be expected that concerns related to negativity and misinformation are more pronounced in some countries than others. As an example, people in the Netherlands are not extremely concerned about their ability to discern true from fake news (30%). Concerns are substantially more salient in other countries included in our survey, such as the United States (64%), the United Kingdom (58%) and France (62%). With our comparative survey, we aim to explore whether perceptions of misinformation and negativity across a diverse set of European countries and polarized countries outside of Europe (India and the United States) are in line with country-level factors that should make the dissemination of actual disinformation and negative news more likely (see Humprecht et al., 2020). For example, are people in polarized settings such as the United States more likely to perceive the risks of negativity and misinformation?

The survey was distributed by a panel company in all countries and a professional service translated the questionnaire to the respective languages (except the survey in India, which was presented in English). Speeding respondents were excluded from the data analysis. The average age was 48.31 (SD = 17.00), 55% identified as female, 44% as male, and 1% as other; the distribution across education was 31% low, 38% medium, and 31% high.

The primary survey items relevant to this study relate to the salience and threat of negativity and misinformation in the news. First, for salience of negativity, we asked respondents to estimate what percentage of all the news is about negative or positive events or topics (range: 0–100). Second, after defining misinformation as false or deceptive information, respondents were asked to estimate the percentage of all news, both in social and established media, that consists of misinformation (range: 0–100). To measure the perceived risk of the informational threats distinguished in this paper, we formulated specific items to measure potential societal consequences that are specifically related to either negativity (e.g., inaccurate worldview, pessimism towards societal progress) or misinformation (e.g., undermining of democracy or increase of polarization) based on previous literature (e.g., Hameleers & van der Meer, 2020; Thesen, 2018; Van Aelst et al., 2017; van der Meer et al., 2019; Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). Third, the perceived threat of negative news was evaluated based on three items on a 7-point Likert scale (a = .85), asking, for example, how negativity in the news creates an inaccurate view of the world and makes it difficult for audiences to make well-informed decisions. Fourth, the threat of misinformation was measured with four 7-point Likert items (a = .92), asking how misinformation can, for example, undermine democracy or distort the truth. The items for negativity in the news were asked in a different part of the survey than those regarding misinformation, to avoid overlap in ways of answering the questions. Appendix A includes all the survey items.

Topics

Bibliography

Acerbi, A., Altay, S., & Mercier, H. (2022). Research note: Fighting misinformation or fighting for information? Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-87

Egelhofer, J. L., & Lecheler, S. (2019). Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: A framework and research agenda. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(2), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1602782

Esser, F., Engesser, S., & Matthes, J. (2016). Negativity. In C. de Vreese, F. Esser, & D. N. Hopmann (Eds.), Comparing political journalism (pp. 89–109). Routledge.

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(27), 15536–15545. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920498117

Hameleers, M., & van der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2020). Misinformation and polarization in a high-choice media environment: How effective are political fact-checkers? Communication Research, 47(2), 227–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218819671

Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2017). What is news? News values revisited (again). Journalism Studies, 18(12), 1470–1488. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1150193

Hermans, L., & Gyldensted, C. (2019). Elements of constructive journalism: Characteristics, practical application and audience valuation. Journalism, 20(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918770537

Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & Van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126

Jacobs, L., Damstra, A., Boukes, M., & De Swert, K. (2018). Back to reality: The complex relationship between patterns in immigration news coverage and real-world developments in Dutch and Flemish newspapers (1999–2015). Mass Communication and Society, 21(4), 473–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1442479

Jungherr, A., & Schroeder, R. (2021). Disinformation and the structural transformations of the public arena: Addressing the actual challenges to democracy. Social Media + Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305121988928

Knuutila, A., Neudert, L.-M., & Howard, P. N. (2022). Who is afraid of fake news? Modeling risk perceptions of misinformation in 142 countries. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-97

Kyriakidou, M., Morani, M., Cushion, S., & Hughes, C. (2023). Audience understandings of disinformation: Navigating news media through a prism of pragmatic scepticism. Journalism, 24(11), 2379–2396. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849221114244

Levine, T. R. (2014). Truth-default theory (TDT): A theory of human deception and deception detection. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(4), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14535916

Luo, M., Hancock, J. T., & Markowitz, D. M. (2022). Credibility perceptions and detection accuracy of fake news headlines on social media: Effects of truth-bias and endorsement cues. Communication Research, 49(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921321

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters Institute digital news report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023

Neyazi, T. A., Kalogeropoulos, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Misinformation concerns and online news participation among internet users in India. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211009013

Osmundsen, M., Bor, A., Vahlstrup, P. B., Bechmann, A., & Petersen, M. B. (2021). Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000290

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Rittichainuwat, B., Nelson, R., & Rahmafitria, F. (2018). Applying the perceived probability of risk and bias toward optimism: Implications for travel decisions in the face of natural disasters. Tourism Management, 66, 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.013

Soroka, S., Fournier, P., & Nir, L. (2019). Cross-national evidence of a negativity bias in psychophysiological reactions to news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(38), 18888–18892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908369116

Soroka, S., & McAdams, S. (2015). News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.881942

Soroka, S. N. (2006). Good news and bad news: Asymmetric responses to economic information. The Journal of Politics, 68(2), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00413.x

Thesen, G. (2018). News content and populist radical right party support. The case of Denmark. Electoral Studies, 56, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.09.003

Trussler, M., & Soroka, S. (2014). Consumer demand for cynical and negative news frames. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214524832

Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H. G., Strömbäck, J., Vliegenthart, R., Damstra, A., & Lindgren, E. (2020). Causes and consequences of mainstream media dissemination of fake news: Literature review and synthesis. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1759443

Tully, M., Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2020). Designing and testing news literacy messages for social media. Mass Communication and Society, 23(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1604970

Van Aelst, P., Strömbäck, J., Aalberg, T., Esser, F., de Vreese, C., Matthes, J., Hopmann, D., Salgado, S., Hubé, N., Stępińska, A., Papathanassopoulos, S., Berganza, R., Legnante, G., Reinemann, C., Sheafer, T., & Stanyer, J. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551

van der Meer, T. G. L. A., & Hameleers, M. (2022). I knew it, the world is falling apart! Combatting a confirmatory negativity bias in audiences’ news selection through news media literacy interventions. Digital Journalism, 10(3), 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.2019074

van der Meer, T. G. L. A., Hameleers, M., & Ohme, J. (2023). Can fighting misinformation have a negative spillover effect? How warnings for the threat of misinformation can decrease general news credibility. Journalism Studies, 24(6), 803–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2187652

van der Meer, T. G. L. A., Kroon, A. C., Verhoeven, P., & Jonkman, J. (2019). Mediatization and the disproportionate attention to negative news: The case of airplane crashes. Journalism Studies, 20(6), 783–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1423632

Van Duyn, E., & Collier, J. (2019). Priming and fake news: The effects of elite discourse on evaluations of news media. Mass Communication and Society, 22(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1511807

Vraga, E. K., Bode, L., & Tully, M. (2020). Creating news literacy messages to enhance expert corrections of misinformation on Twitter. Communication Research, 49(2), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219898094

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking (Vol. 27). Council of Europe. http://tverezo.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PREMS-162317-GBR-2018-Report-desinformation-A4-BAT.pdf

Funding

This study is supported by VENI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) under grant number: 016.Veni.195.067.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The research protocol employed was approved by the researcher’s institutional review board at the University of Amsterdam. Human subjects were provided informed consent.

Copyright

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

Data Availability

All materials needed to replicate this study are available via the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1XAX7C