“From the complex to the simple line”: Some notes on Matisse and Poulenc

Jay Palombella shares his reflections on Matisse’s sketches in light of their influence on the life and work of composer Francis Poulenc.

Just one week ago, I found myself in the Matisse Museum in Nice and I was annoyed. Not at the price of my ticket, as I so often am when I visit galleries abroad and foolishly admit to being English – not a wise decision post-Brexit. No, my ticket was free. Nor was I annoyed at the usual hordes of Italian school children running around the place, for they seemed strangely subdued and nonintrusive there. No, my annoyance stemmed from a deep and unfathomable sense of betrayal. There I was standing in the eponymous museum of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century and all I was presented with was his sketches, in between which hung a succession of huge portraits by Djamel Tatah, some bloke from Lyon who had apparently found vague inspiration in Matisse. I completed a quicker-than-usual circuit of the gallery, slouched down on a sofa in the foyer and flicked through the untranslated pages of the exhibition guide. I felt hard done by. Where were the huge canvases? The dynamic uses of colour? Those bright portraits that seem to drip away in fauvist hues? Of course I had seen his sketches before, but they seemed not even half as interesting as the paintings. However, not wanting to waste my free ticket, I tried again. Beginning in the first room…I worked my way up.

This time around I decided to listen to some music and chose Francis Poulenc. Poulenc was a French composer writing at a similar time to Matisse and, to my mind, they have always shared a similar sense of playfulness and colour. Poulenc seemed the perfect fit. I remembered how he, following a visit to Vienna where he had heard the new musical ideas of Schoenberg and Webern, came to reconsider his own musical style. While he was already a renowned composer at that point, he was chiefly celebrated as a farceur who composed playful songs and miniatures, like his ‘Trois mouvements perpétuels’ or the song cycle ‘Le bestiaire’. He wanted to make his compositions sound more complex and developed, reminiscent of the musical leaps made by those at the Second Viennese School. Following this visit, a self-conscious shift can be evidenced in his composition style. Through works like ‘Quatre poèmes de Max Jacob’, his compositions became a way to show off increasingly dissonant harmonic language with dense accompaniments of considerable technical difficulty. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this process of cramming his once playful miniatures with heavily laden harmonic complexity was unsuccessful and he was again left at a point of musical disillusionment.

“it was this negation between complexity and simplicity so expertly rendered by Matisse that prompted Poulenc to reconsider his ‘new’ style”

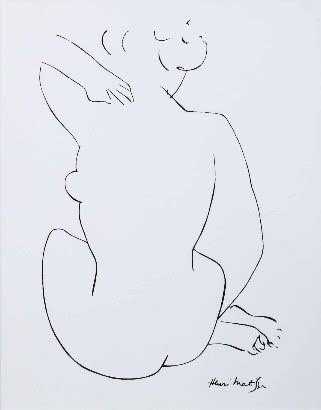

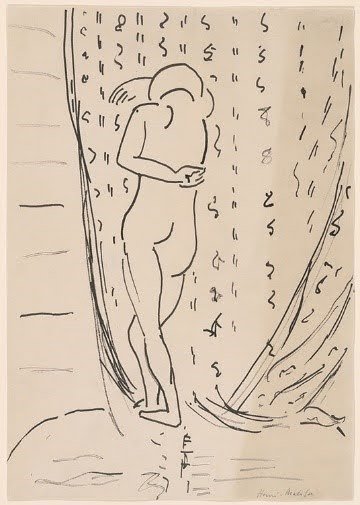

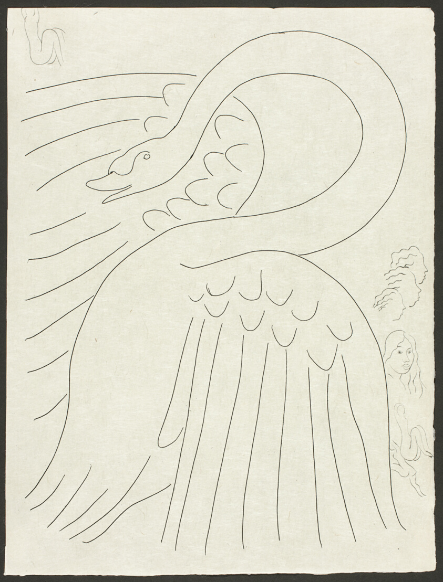

It was at this point, as I would later find out, that Poulenc came across Matisse’s illustration of Mallarme’s poems. They provoked something in him, he writes: ‘I cannot tell you how much his [Matisse’s] sketches for Mallarme’s poems affected me…You could see in them the same subject, in particular a swan, in three for four stages, which always went from complex and thick to the most ideally simple and pure pen strokes’. Poulenc noticed something about Matisse and his sketches that perhaps I, at first, didn’t. An unashamed simplicity. Indeed, it was this negation between complexity and simplicity so expertly rendered by Matisse that prompted Poulenc to reconsider his ‘new’ style, as he bemoans histrionically: ‘Alas! Why didn’t I follow Matisse’s lesson in my piano pieces!’.

Matisse entirely altered Poulenc’s way of looking at composing. As he would later write in his ‘Journal de mes mélodies’: ‘while composing these mélodies I thought frequently of an exhibition of drawings by Matisse…where the pencil drawings could be viewed, full of hatching, of repetitions, and the final proof retaining nothing but the essential, in a single stroke of a pen’. I looked again at these sketches. My Spotify shuffle flicked to play the first movement of Poulenc’s Clarinet Sonata, one of the works written during this later period of composition. I was wrong to feel hard done by. Of course, the lack of those large, consuming canvases was unexpected, but without them, and for a second time, I came to look at a different side of Matisse. Within these ‘simple and pure pen strokes’ I saw a similar sense of excitement and brightness that I had previously found in his portraits. Just this time, it seemed to be condensed down as if a purer essence of itself. There is something to be taken from Poulenc’s reading of Matisse, whether this is some grand postulation for life or an encouragement to perhaps give an exhibition a second chance. I’m unsure, but in the prophetic words of Poulenc as he sets out his desire for future compositions: ‘Taking my inspiration from the drawings of Matisse, I am trying to go from the complex to the simple line’.

Quotations from Buckland’s 1999 Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature and Roger’s 2020 Poulenc: A Biography.