The Rise and Fall of Eliot Ness

The true story behind The Untouchables

Eliot Ness and his squad of Untouchables set out to smash Al Capone. But their antics were mostly for show, and Ness’ post-Chicago career was less than illustrious.

In 2014, US senators Richard Durbin, Sherrod Brown and Mark Kirk proposed a tribute to the prohibition-era Federal Agent Eliot Ness. In recognition of Ness’ world famous heroics as an enforcer of law and order, they wanted to rename the national headquarters of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in Washington DC in his honour. It would probably have been uncontroversial had those heroics been incontrovertibly true. For many critics, however, the Ness that became known to the public through decades of books, TV shows and movies is arguably almost entirely fictional: a mythologised version of a man who, while he had his share of successes, was far less remarkable. “Naming a building after him for his role in bringing down Al Capone?” snorted Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. “You might as well name it after Batman.”

Ness, clearly enough, was not an inspiration for the Caped Crusader, but he did provide the basis for another comic strip hero. The square-jawed crime fighter Dick Tracy first appeared in the early 1930s, created by cartoonist Chester Gould. In later years the character fought outlandish freaks, but in his early days his beat, like Ness’ was Chicago (more-or-less: the city was unnamed but it was clear where it was), and his enemies were mobsters like “Big Boy”, obviously modelled on Al Capone.

“I’ve always been disgusted when I read or learn of gangsters and criminals escaping their just dues under the law,” Gould said in 1934. “For that reason I invented in Dick Tracy a detective who could either shoot down these public enemies or put them in jail where they belong.” Five years earlier in 1929, Eliot Ness and his “Untouchables” had been “created” for much the same reasons.

Eliot Ness was Chicago born and bred. His parents, both Norwegian immigrants, were sober and responsible middle class citizens who owned and ran a bakery, instilling their work ethic into their five children, of whom Eliot was the last to arrive on April 19, 1903. Young Eliot worked in the bakery, delivered newspapers, did well at Fenger High School on Chicago’s south side, and enjoyed reading; particularly mysteries. He always dressed unusually well, prompting school friends to tease him with the nickname “Elegant Mess”. When his eldest sister, Clara, married a man named Alexander Jamie, who worked for the US Treasury Department in the Prohibition Bureau, Ness found his greatest role model. Jamie proved a profound formative influence on Eliot, encouraging his passion for stories of law enforcement and detective work, as well as teaching him to shoot.

Ness graduated from the University of Chicago in 1925 with a first class degree in political science, commerce and business administration, and spent a year as an investigator for the Retail Credit Company in Chicago. He then returned to academia for postgraduate work with August Vollmer, a pioneer in the nascent field of Criminal Justice. And when his studies were finally complete in 1928, Jamie, by now the Chief Investigator in the Prohibition Bureau, brought Ness in to work as an agent. Jamie himself would eventually rise to the position of head of the Chicago branch of the FBI.

By 1928, Al Capone was at the peak of his power, little realising that the only way from there was down. The first signs of his descent were already visible. He’d tried and failed to leave Chicago and expand his operations further afield. New Chicago Chief of Police Mike Hughes had put hundreds more officers on the streets as part of his promise to crack down on mob activity. And Herbert Hoover, the new president of the Chicago Crime Commission (and future US President), was determined to bring Capone to book. Chicago’s mayor might still have been turning a blind eye to Capone, but the rest of the establishment had had enough of living under his shadow. Hoover brought in US Attorney George E.Q. Johnson to handle the situation, and Johnson in turn tapped Treasury Department chief Elmer Irey and IRS agent Frank Wilson to launch a detailed investigation into Capone’s financial affairs. The second point of Johnson’s two-pronged attack on Capone was an assault on his actual operations: crippling them as they were actually in progress.

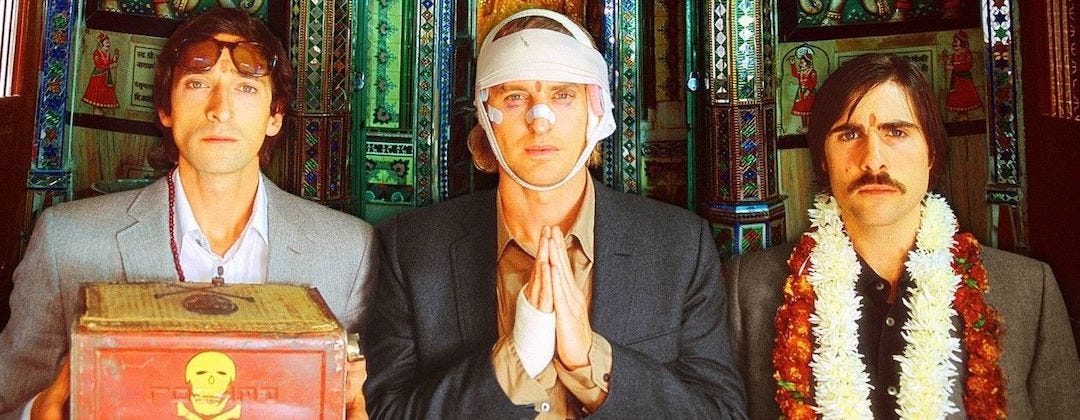

For the latter, Johnson recruited Ness to put together a team. Ness had already garnered himself a reputation as a “boy scout” who could not be corrupted. At this time in Chicago, vast numbers of law enforcement officers were on the take, but Ness had turned down an offer of $2000 a week (almost as much as Ness earned in a year) from Capone himself to keep the illegal status quo in which the booze illicitly flowed. “I may only be a poor baker’s son,” he’s reputed to have said, “but Eliot Ness can’t be bought: not for two thousand a week, ten thousand or a hundred thousand. Not for all the money they’ll ever lay their scummy hands on.” The outfit Ness eventually put together was formed of a dozen men including himself who Ness hand-picked from more than fifty applicants: men who, like Ness, had proved they could not be intimidated or bribed. Recruited from around the country, several were First World War veterans chosen for specialist skills that complemented those of the rest of the squad.

“I ticked off the general qualities I desired,” Ness later described in his autobiography. “[The men should be] single, no older than 30, [with] both the mental and physical stamina to work long hours and the courage and ability to use fist or gun and special investigative techniques. I needed a good telephone man, one who could tap a wire with speed and precision. I needed men who were excellent drivers, for much of our success would depend upon how expertly they could tail the mob’s cars and trucks… and fresh faces from other divisions who were not known to the Chicago mobsters.”

This band of incorruptible tough guys was almost immediately dubbed “The Untouchables” by a Chicago newspaper. The name stuck, and while the work that actually brought Capone to book — the rather prosaic business of exposing his tax evasion — was carried on behind closed doors by the methodical Irey and Wilson, Ness and his Untouchables went about making headlines with showier stunts. They were certainly a successful irritant to Capone, but they were essentially a Public Relations operation. It worked. Where Capone had managed to get a reputation as a Robin Hood figure in some circles, even somewhat beloved of the media who could always rely on him for a mischievous soundbite, the arrival of the Untouchables changed the popular narrative to one of straight-up good guys vs. gangster bad guys, and Capone, particularly after the brutal and game-changing St Valentines Day Massacre was on the wrong side.

The principal source of Capone’s income was the breweries that produced his illegal liquor, so Ness and his men immediately began to stake out the “speakeasies” where Capone’s booze was sold, in order to follow the trucks that delivered the barrels back to their points of origin. Once a brewery was conclusively identified (some were huge, taking up multiple stories in their buildings) Ness hit upon the shock-and-awe tactic of smashing through its doors in a flatbed truck with a snow-plow mounted on the front. The speed and violence of this procedure gave those inside the buildings no time to get away, and indeed, no warning that a raid was even imminent. Capone’s stunned employees were forced to simply stand idly by as Ness and his Untouchables destroyed stockpiled barrels of beer and whiskey, allowing the contents — and Capone’s profits — to seep away into the earth.

Capone and his men were no longer safe to operate out in the open without fear of arrest. The trucks had to go, with the rather less efficient system of smuggling barrels in ordinary sized cars — which could only carry about four at a time — replacing them. Records of conservations obtained through Ness’ wire taps revealed Capone was becoming rattled, not least because he was fighting opponents he didn’t understand. If they couldn’t be bribed or strong-armed, then what were his options? One story has two of Ness’ team having packets of money thrown at them through their car windows, to which their response was to chase down their surprise benefactors and throw the money back at them. There were attempts on Ness’ life and the lives of his men. But Ness’ response was to doggedly and methodically continue on his chosen course of action. He organised a parade of Capone’s confiscated trucks to be driven past Capone’s own hotel. Reports of Capone’s fury became legendary. But when a tapped phone conversation revealed that one speakeasy had run dry because there was no booze that could be delivered there, Ness knew that he was winning.

The issue remained, however, that these were still PR victories, rather than events that would accumulate into Capone’s ultimate downfall. Prohibition was an unpopular law, and the feeling among Chicago’s legal community was that the public, and by extension any jury, might still be lenient towards Capone in a court setting, given that his activities were ultimately still providing something people wanted: alcoholic drinks. What the public couldn’t abide was a tax cheat, so it was on that basis that Capone was finally indicted. While the Untouchables were out making a noise, Frank Wilson, entirely separately, was putting in the work that would really “get” Capone. The gangster, if he was concerned about anything, was worried about staving off potential murder charges. He wasn’t giving much thought to his tax irregularities.

Wilson, like Ness, carried an excellent reputation within his own field of expertise. His colleague Elmer L. Irey said that Wilson “fears nothing that walks,” and would “sit quietly looking at books eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, forever, if he wants to find something.” Wilson’s exhaustive trawl through any document possibly remotely pertaining to Capone’s financial operations eventually led to the discovery of a significant interest in a greyhound racing track, the ledgers of which occasionally mentioned large payments to someone referred to only as “Al”. Wilson spent three weeks checking documents from bank deposits to voter registrations in a meticulous attempt to identify the handwriting in the “Al” notes, and, incredibly, finally did so via a deposit slip from a Cicero bank. The scrawl belonged to a bookkeeper named Shumway, who agreed to testify about this subsection of Capone’s income. While Ness was out smashing distilleries, the seeds of Capone’s downfall were actually sown by some small pieces of paper.

In Cicero a man named Reis was identified as making huge deposits of cash (in sacks), which he converted to cashier’s cheques and filtered back directly to Capone. Reis too was strong-armed into testifying. Capone noticed that Shumway and Reis had both apparently disappeared (presumably into protective custody), caught wind of the financial investigation, and actually hired assassins to kill Wilson. He called off the hit when he learned that his thugs were already known to the State Attorney’s office and might end up incriminating him further. Finally, with Wilson’s Treasury Department case deemed rock solid, Capone was indicted on 23 counts of tax evasion by a grand jury in June, 1931. He was given an 11-year sentence on the brutal prison rock of Alcatraz, and his reign was over.

Ness was still a young man of 28, and found himself in the peculiar position of being somewhat renowned (where he was recognised at all) as the man who brought down Capone while having really done no such thing. After all Ness’ showmanship in battling Capone, the gangster’s real demise must have seemed anticlimactic to the fresh-faced agent. The Untouchables were disbanded to go their separate ways, and Ness continued working at Chicago’s Prohibition Bureau, where he was promoted to Chief Investigator. And when Prohibition was repealed in 1933, he became an alcohol tax agent in the Appalachian mountains of southern Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee: nicknamed the “moonshine mountains” due to their reputation as notorious outposts of renegade hooch stills. He averaged an incredible one-a-day rate for the shutting down of illegal bootlegging operations. Within a year there were almost none still operating in the Appalachians.

Ness was transferred to Cleveland, Ohio in 1934, and a year later Mayor Harold Burton hired him as the city’s safety director in charge of the police and fire departments. His appointment was enthusiastically reported by the press, with whom Ness maintained the cordial relationships that had benefitted him in Chicago. “If any man knows the inside of the crime situation here,” raved one editorial, “his name is Ness. The mere announcement of his selection is worth a squadron of police in the effect it will have on the underworld’s peace of mind.”

Burton had been elected on a law-and-order platform, pledging war on organised crime and on corruption within his own police and fire departments. Ness immediately set about cleaning up the town for him. The sloppy, disorganised and often dishonest law enforcement institutions at that time in Cleveland were initially unimpressed with Ness, who appeared mild-mannered and bookish on first meeting. But they soon realised they had underestimated him. To those who were on the level he was fair, making sure they knew his door was always open, and striving to provide them with equipment which they may previously have lacked due to underfunding or legislative indifference. Those he found to be morally compromised, however, found themselves the subject of intense investigations, with Ness even employing wire-taps just as he had in Chicago. He hired a new team of “untouchables” this time known as the “Secret Six”, sourced from outside Cleveland and therefore with no ties of loyalty within the Cleveland Police Department. He promoted honest and capable officers and demoted crooked and incompetent ones (he even busted the head of the Detective Bureau, Emmet Potts, down to traffic duty).

“With an innocent smile, this scientific sleuth recently rounded up 100 witnesses, convicted two police captains of taking bribes and indicted seven other guardians of the law,” boasted a 1937 American Magazine article on Ness’ behalf. “(He has) personally led raids on gangsters, gamblers, and vice barons, and brings back industries driven from Cleveland by racketeers. He has ousted incompetents and political hangers-on from the police, fire and building departments and taught the ‘boys’ that it’s dynamite to mess with Ness-men!”

Taking a hands-on approach, he personally visited every one of the precincts under his control. “I am not going to be a remote director,” he promised. “I’ll cover this town pretty well…” And he wasn’t just concerned with Internal Affairs. Perhaps his greatest achievement of this period was the shutting down of mob gambling den The Harvard Club, despite it being technically outside his jurisdiction. While not a spectacular takedown, the raid nevertheless resulted in the arrests of 20 gangsters and the closing of a notorious establishment. The press were on hand to take pictures of Ness at the scene and trumpet that Ness’ trademark brand of mob busting had come to Cleveland. The PR machine was still working.

But sadly for Ness, he had peaked early, and his career in Cleveland began a steep decline in the late 1930s. He failed to secure a conviction in the case of the grisly — and still officially unsolved — “Cleveland Torso Murders”, and his reputation for moral probity took a hit when he went through a messy divorce (he first married in 1929 and would marry twice more in the next two decades). He became well known as an enthusiastic social drinker, the irony of which was not lost on a press well acquainted with his erstwhile career enforcing Prohibition. And when he was involved in a drunk-driving accident, the man who had spent years trying to root out corruption in the police department tried unsuccessfully to get the incident covered up. He was forced to resign his position as Cleveland’s Safety Director in the resultant scandal.

He next moved to Washington DC where he worked for the federal government, specifically targeting prostitution around US military bases. He also attempted a number of business start-ups, all of which failed. He eventually became chairman of the Diebold Corporation, which manufactured safes, and by 1947 he was back in Cleveland in an ill-advised bid to get elected as mayor. He was resoundingly defeated by a majority of two to one, having burned through his savings and racked up significant debts during the campaign. Diebold expelled him from their board, and the final jobs of his life were comparatively menial: he ended up selling wholesale electronic components, and frozen hamburgers to restaurants.

Finally, he ended up in the rural town of Coudersport, Pennsylvania: his just-about extant reputation as a law enforcement expert having landed him a position with a company that specialised in watermarking documents to prevent counterfeiting. In that small town he became a relatively big personality once again, even if it was only as a raconteur in bars, telling the stories of his glory days in Chicago. Encouraged by the reactions, he began collaborating on an autobiography with United Press International sports reporter Oscar Fraley. Much embellished, The Untouchables was full of action: gun battles and car chases and noble men standing up for what was right in the face of despicable villainy from gangsters and crooked coppers with no respect for the law. In 1931 Chester Gould had created Dick Tracy using the young Ness as inspiration. Now, in 1957, Ness was reinventing his own life story in Dick Tracy’s image.

Ness died from a heart attack that same year at the age of 54, and his book was published posthumously. It created a sensation, selling 1.5 million copies and inspiring first a successful TV series and, 30 years later, a movie immediately regarded as a modern classic. The “Eliot Ness” in the public consciousness today is arguably more Kevin Costner than it is the real man. But after his later-life fall from grace, the real Ness would be more than happy that his legend as an American hero lives on.

The second annual Eliot Ness Fest takes place in Coudersport in July, 2019.

This feature was originally published in All About History: The Book of Prohibition, October 2018.