I've Been Daily Driving My 1962 Chevrolet Corvair Monza Coupe for a Full Year Now, and I Love It

What's good, and what's on the to-do list.

05/10/2022

April 22, 2022, marked a year since I purchased my Corvair. Shortly after my then-13-year-old son, Jasper, and I flew to Michigan and drove it back to southwest Vermont. I’ve been using it as my everyday transportation for just over a year, and that naturally brings me to look back and forward at experiences with the car.

This is my fourth daily-driven 1960s compact. I started with a 1961 Ford Falcon Futura, then I had a 1964 Rambler American 330, then I had a 1962 Falcon Deluxe Tudor, and now I have a 1962 Corvair Monza coupe. This is my first Corvair and I love it. I’d get another (probably a ’60 or ’61 700-series sedan) if I had the room and resources.

Why a Corvair? Well, we found ourselves needing both a family car and something “go anywhere” and utilitarian. As it happened, my wife lucked into her grandfather’s 1983 Cadillac Sedan de Ville, which I’ve written about on occasion. That squared away the family-car situation, leaving me initially looking at pricey Willys products.

Then I remembered that Corvairs had a reputation for being good in the snow, thanks to their rear-engine/rear-drive layout. I’ve also long admired rally cars and an encounter with Safari’d Porsches at the 2018 Greenwich Concours had already made me see those cars in a new light. Equally persuasive were the facts that one of the top Corvair parts suppliers, Clark’s, is right in my back yard in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts; and CORSA, the Corvair Society of America, is an extremely active, highly inclusive club.

A Corvair, I thought, perfectly checked all the boxes for daily driver status. Twelve months in and I’m happy to report that I was not wrong. I found my car, which came to me with the name Ruth, in Spring Lake, Michigan, quite close to where I grew up. A friend from high school looked the car over for me and reported back that it was as-represented by the seller, so I bought it and arranged license plates and insurance. Jasper and I flew into Detroit, hitched a ride with a Detroit-area friend to Spring Lake, and retrieved Ruth from my high-school friend’s garage (I haven’t actually met the seller, though we’ve become pretty well acquainted since thanks to social media: #acorvairnamedruth).

Jasper and I took nearly three days to drive Ruth back, stopping for the night in the Detroit area and in Western New York. We stuck to 55 mph roads, stocked a fanbelt and ignition parts just in case, and had enough tools to seemingly deal with any kind of roadside carnage that might befall us. The car ran like a top, drove perfectly, and covered the 730-some mile distance with zero drama whatsoever.

That was a good indication as to how things would go in my first year of ownership, as I’ve divided the car up into systems and kept track of the needs and wants for each, plus my progress in repairs and maintenance. I've made steady progress towards improvements (though, naturally, never at the rate I’d like), and overall Corvair ownership has been a happy experience. I even managed not to get asphyxiated by my heater.

The Structure

Everyone knows that rust can be terminal. While anything humans have built can be repaired by other humans, some repairs exceed economic sanity. When I was searching for a Corvair, my two criteria were that it be solid enough not to need immediate chassis restoration and that I could drive it home. I had to pass on both good-running-but-rotten candidates and at least one gorgeous car from the Southwest that had been towed home but was not in driving condition. After the disheartening experience of watching my ’60 Dodge sit in the driveway for years, I knew I needed something I could keep running rather than something I needed to get running.

My Corvair, Ruth, which was born in California and moved to Michigan circa 1969, was rock solid. There are repaired and unrepaired holes in the floors, yes, and some raunchy plastic filler/expanded foam “body work,” but all the structural elements are in good shape. I have a strict regime of washing and lanolin-based undercoating planned to keep the elements at bay. Currently, the car undercoats itself at the back end, but new gaskets for the oil pan, valve covers, and the oil-fill neck are all planned. The notorious pushrod O-rings don’t seem to leak, but then this car was in service into the 1990s, it appears, so maybe it had the Viton thing done back then.

The Front Suspension and Steering

There is definitely some play somewhere between the steering wheel and the front tires. After a year of regular use, I barely even notice the constant little corrections necessary to keep going straight down the road, but it’s still something that requires correction. The natural inclination for anyone talking about a non-rack-and-pinion car is to blame the steering box, but a lot of reading from various sources indicates that more often the problem is typically worn and dry suspension and steering-linkage bushings, rather than the box itself.

I’d also like to get the nose another inch or two higher in the air. I e-mailed the folks at Eaton Detroit Spring to see if they could help, only to learn that Corvair springs are still on the drawing board there. It is possible heavy-duty aftermarket springs might get me the lift I’m after, but they’re deliberately designed not to have much of an effect on ride height. After all, most Corvair owners are more interested in going down not up. I’m investigating spacers, but it’s a low-priority project at the moment.

Rear Suspension and Differential

One thing I’ve learned since I became a Corvair owner is that the most “unobtanium” general-service part for an Early Model is the unique rear-wheel bearings. They’re a sealed unit designed to move on multiple axes to compensate for the action of the swing axles. They haven’t been made in years and good units trade in the neighborhood of $350 apiece or more. Better yet, the 1963 and ’64 parts were redesigned and aren’t compatible with a ’62 like mine.

Thankfully, mine are still quiet and seem to function perfectly. Drilling grease fittings and applying regular lubrication is said to be the ticket for keeping the original “disposable” units in service seemingly indefinitely. That’s a project I’ll be pursuing sooner or later.

As in the front, I’d like to lift things slightly. I like the car’s current slightly nose-up rake, but since the nose is already meant to go higher and I’d like to retain the current proportions, that means the rear should come up an equal amount. As an alternative, the Corvair could probably stand new shock absorbers at all four corners. Stiffer shocks and no lift may avoid the rubbing issues and negate the need to go up entirely.

The differential currently in the car (and presumably original to it) bears the “HC” stamp of 3.27 gears. That meant that on the trip home the car was willing to cruise at 65 or 70 mph when the opportunity arose, but sometimes it runs out of breath near the tops of the steeper local hills. The 25.5-inch diameter snow tires look amazing and work really well as tires, but they reduce the effective gearing of the 3.27s even further.

My ideal setup for this car involves a limited-slip differential and 3.55 or maybe even 3.89 gears. Freeway flying is not this car’s modus operandi, but frequent trips around the area are. I’d rather have the acceleration and hill-climbing ability than top speed.

Brakes, Wheels and Tires

I am not alarmed by 9-inch manual drum brakes. Not any place I’ve lived, anyway. I drove my Falcons and Rambler (plus a ’50 Studebaker Champion) all over Michigan without issue and my experience with the Corvair in Vermont has been the same. If I commuted in LA, I would no doubt feel differently. My brakes do need to be adjusted, however. Self-adjusting drums didn’t make their way to the Corvair until 1963. I also expect to need linings soon, but overall I cannot fault the stock brakes one bit.

I have had one brake-related incident. Late last June, a major pothole attempted to eat my left rear wheel as I turned into a parking lot. The Corvair made it all the way to a parking space just as the pedal went to the floor. That incident, combined with the completely uneventful, 836-mile trip back from Michigan to Vermont, and the ease with which every project has gone thus far, has convinced me this is a “lucky” car determined to remain in my ownership.

A brake hose had been torn in half and, because of the original single-reservoir master cylinder, we had no brakes 30 miles from home after 5:00 on a Friday. That led to new brake hoses and a dual master cylinder to ensure any future loss of brake pressure doesn’t take the entire system with it.

The wheels and tires were the first thing I changed when I got my Corvair home. It came with 13-inch steel wheels and a set of undersized and distressingly cracked 165/80R13 radials. The proper stock-replacement size is actually 185/80R13, but I’ve never been a fan of 13-inch wheels. My ’61 Falcon wore ’65 Mustang 14-inch wheels and my ’62 wore 14-inch steelies off a Maverick. The Rambler came stock with 14-inch wheels and I always thought that was a much more practical arrangement.

Because it was purchased in the fall of 2013 and sold in the summer of 2014, the Rambler wore a set of brand-new P195/75R14 Firestone Winterforce snow tires the whole time I owned it. I kept those tires when I sold the car and subsequently ran them on my ’61 Falcon in the winter of 2014-’15 and on my ’62 Falcon in the winter of 2015-’16.

The current owner of my ’62 Falcon has no intention of ever driving it in the snow and was kind enough to sell those wheels and tires back to me for the cost of shipment. Our local machine shop bored out the Maverick wheel centers to Corvair size and I judged the 2000 Chevrolet Indigo Blue metallic a close enough match to the Corvair’s original Nassau Blue for them to look like original equipment.

The hubcaps, selected primarily on price and suitably decrepit condition, are of the 1958-’59 Chevrolet type (I just call ’em ’59 Biscayne caps, for short) and echo the (currently missing) 102-hp Super Turbo-Air badge on the deck lid. Dog-dish hubcaps have been on every old car I’ve owned at this point. I like the rugged look they give on the Corvair, something akin to a 350-hp 348 Biscayne Super Stocker or a fuelie Corvette tanker from that era.

Engine

Corvair engine offerings in 1962 were a bit confusing. They were all 145-cu.in. horizontally opposed, air-cooled six cylinders. That was equally true for 1961-’63; in ’60 they were 140-cu.in. and in ’64 they got stroked out to 164-cu.in. If you bought a car with a manual transmission and didn’t select an optional engine, you got the 80-hp Turbo-Air engine. If you paid for the premium Monza trim and opted for a Powerglide automatic transmission, you defaulted to an 84-hp Turbo-Air (the four-horse gain was thanks to a bump in compression from 8.0:1 to 9.0:1).

Before the turbocharged 150-hp Monza Spyder came out, the sporty Corvair engine was the Super Turbo-Air, which made 102 hp in 1962 (and ’63). It was available in any non-van Corvair and made its extra power through a hotter camshaft, rejetted carburetors, and larger exhaust tubing.

If the stamping on the top of the engine is to be believed, my car has a (presumably original) 102-hp engine. The cylinder head numbers would tell the tale more fully, but as I haven’t pulled off the lower shrouds yet, I haven’t seen them.

I don’t know what the mileage is on my engine, but it still runs well (although it leaks like a sieve—something to be addressed very soon). Sooner or later, however, it will need attention. My hope is to have a fresh 110-hp, 164-cu.in. engine waiting for that moment so I can minimize downtime. The 110-hp engine occupied the same place in the engine hierarchy from 1964-’69 that the 102-hp engine did in 1962-’63. The longer stroke and its accompanying torque will be most welcome for hill climbing.

Transmission

It’s a Powerglide, which I am kind of enjoying. Every ’50s and ’60s car I’ve owned up to this point has been a manual transmission, save my first. My ’68 Camaro started life as a Powerglide, so the Corvair gives me some nice historical symmetry, but Dad and I swapped in a Hurst-shifted Muncie into the Camaro when I was in college. I’ve got no plans to four-speed swap the Corvair, as buying an automatic was always part of the plan. I’d hoped my dear wife could be convinced to drive the Corvair on occasion, thanks to the lack of a clutch pedal, but she’s declined thus far. Perhaps once the car’s a little less rough around the edges she'll be more inclined.

Jasper gets his learner’s permit in less than a year—then there are two more behind him. He’s already driven the Corvair once, in a parking lot, and seems to be pretty natural with accelerator use and gentle braking—putting him a leg up on me at that age. While I’ve long advocated the path of learning on a stick and introducing an automatic later, it does take one factor out of the teaching-a-teen-to-drive scenario, which will probably make my job as Dad easier.

The ’Glide, as mentioned, is leaky but shifts nicely. I want to improve the pan fitment and otherwise plan to leave it alone until it tells me it needs attention.

Body and Paint

Who knows when Ruth was painted her current blue-green color? According to the trim tags and various unpainted areas, when it rolled out of the Oakland plant in November of 1961, Ruth was Nassau Blue. The blue-green reminds me a lot of a Ford/Lincoln/Mercury hue from the late ’60s known variously as Gulfstream Aqua, Madras Blue, Dark Aqua, Dark Bright Aqua, and Young Turquoise (like Young Turk, I guess).

I suspect it’s an Earl Scheib job, but I rather like the color and the fact that it’s mostly all there. It also makes the primered hood look like an intentional tribute to the Mach 1 Mustang. The Ford-esque color on a Chevrolet also seems fitting, as my ’68 Camaro wound up being painted a 1974-’75 Ford color called Green Glow.

The flat-black luggage-compartment lid and engine cover are a legacy of an owner previous to the seller who informed me on Facebook that he’d swapped out those items for his own car. I’d like to repaint the engine cover blue-green and put proper flat-black paint on the nose. Professional body and paint are definitely not a part of the program, however. Having something that nice is the opposite of the point here. It would just stress me out.

Instead, I’ve got some Ford/New Holland blue and John Deere green tractor enamel and I’m going to attempt to formulate a (non-metallic) match that will give better protection than primer and serve as a general touch-up paint around the body. I’ve often thought of antique-tractor restoration as a good frame of reference for this whole project, in fact.

My long-term wish list for the exterior includes a wood-and-metal roof rack to expand my hauling capacity somewhat: You can’t stick oversized loads in the front trunk of a Corvair. I’d also like a passenger-side mirror, embarrassingly, as it would make it a lot easier to pull out of the drive-thru line at the local fast-food joints. I’ve also got a few bits of trim I’d like to reinstall (that 102-hp badge, for one) and I’ve contemplated installing a light-duty trailer hitch. I think I’ve got enough ’20s and ’30s Chevrolet parts around here that I could create a pretty cool utility trailer, but I digress…

Controls and Instruments

Stock instrumentation in a non-Spyder Corvair consists of the speedometer, the fuel gauge, and two warning lights: gen/fan and temp/press. My speedometer works pretty well and it’s even fairly accurate with the taller tires. The cable is a bit noisy in extremely cold weather and should be lubricated. In fact, I have a comprehensive lubrication program planned for the very near future, involving just about everything from the glovebox hinge to the front suspension.

As is so often the case with old cars of unknown provenance, the gas gauge cannot be trusted. It doesn’t register a full tank, stopping at ¾ even when you’ve put in the full 14 gallons. It also drops to E very quickly, hanging there for probably half a tank. That’s not the gauge’s fault, however. I just need to pull out the sender and see what’s going on. It’s a task I’m unhappily rather familiar with from my Falcon days.

Warning lights are fine, and I want to retain them, but I also like to know what’s going on even before things get potentially catastrophic. My traditional gauge preferences are a 4 3/8-inch tachometer on the column or dash and then an under-dash triple panel with matched 2- or 2 1/16-inch instruments indicating oil pressure, temperature, and voltage. The only difference with a Corvair is that I’ll be tracking oil temperature instead of “water.”

The tachometer I’ll be installing, a Detroit-built New Vintage USA 1967-series unit, was originally intended for my ’62 Falcon. For the under-dash panel, I’m debating between ISSPRO gauges, built in Portland, Oregon, or vintage, Chicago-built Stewart-Warner pieces.

Before I install gauges, though, I have more pressing tasks in making the passenger compartment more habitable: I went this past winter without heat. Automotive HVAC projects are not glamorous work, but I missed a Christmas party because I was too cold to drive there, and I am not gonna let that happen again.

As most are, my Corvair is equipped with the hot-air heating system that came out for 1961 rather than the gasoline-fired heater offered from 1960 to ’63. The heater ducts hot air from around the engine into the passenger compartment. It relies on a system of sheetmetal ducts and corrugated hoses to convey that warm air up to your feet and the windshield.

My heating system has several issues: the fan doesn’t work, the hoses are coming apart, and there are holes in several of the ducts. It also should be cleaned so the heated air isn’t conveying the smells of old oil (or worse) with it from the engine. Sometime this summer I’ll be doing a deep clean on the ductwork, lubricating control cables, replacing hoses, getting the fan going and finding out where I need to re-seal things.

If the rebuilt heating system is still no good, Corvair Ranch seems to offer a gasoline heater retrofit built from modern light-aircraft components. That’s good, because original Corvair gas-heater pieces are in demand and hard to find.

Fuel System

The first time I ran the gas tank dry (see faulty gas gauge discussion), I plugged up the driver’s side carburetor with junk from the fuel tank, leading to my disassembling, cleaning and re-gasketing my first Rochester Model H. I also got an early introduction to the seemingly intimidating task of carburetor synchronization. I used the “Finch method” described in How to Keep Your Corvair Alive and haven’t had any issues aside from initially setting the idle too low for a Powerglide car.

Although I’ve had no carburetor issues from dirty fuel since, I really should clean and reseal my fuel tank and inspect the area above it for rust that needs arresting. There are two non-original inline fuel filters on my car: one near the tank and one in the engine bay. The engine-bay unit, at least, needs to go away: The rubber fuel hoses used to splice it into the lines are vulnerable if the fanbelt should break, quite possibly leading to a fire.

As of this writing, I’m actually testing a fuel-system cleaner in the Corvair. I have a suspicion that one or both of the inline filters has partially clogged, leading to a miss in certain situations that doesn’t seem to be ignition related. I was about to replace the filters when the product came to my attention and I thought I’d give it a chance.

Electrical

Currently, no pun intended, Ruth is languishing in my driveway with a broken generator. The generator itself works fine and always has, but one of the bolts securing the commutator end vibrated loose a couple times, putting too much strain on the bolts at the drive end. One of them broke, and while everything is still charging, I cannot abide the generator flopping around and beating itself against the broken mount.

Clark’s no longer stocks the broken drive-end end-frame piece and NOS units are $65 or more online. Thinking I was being thrifty, I purchased a used generator that turned out not to be a perfect match—it may be a 1962 generator (the tag is defaced) but it turns out my car had been upgraded to a 1964 generator. That’s a fact I discovered when I couldn’t remove it per the 1961 service manual: The 1964 supplement informed me that the larger-diameter pulley used on the 35A 1964 generator has to come off the snout before the drive-end frame can be removed from its mounts.

I’m hoping to build a hybrid of the two generators for temporary service while I have a friend weld the ear on the original drive-end frame. I’m currently stuck because I can’t get the ball bearing out. I plan to apply heat, but the arrival of nice weather has put the whole project on hold while I dive into a garage-door installation (watch this space!). I also managed to drop the entire tray of parts while putting them away, losing one of the through bolts under a shelf in the process. I’ll be spending some quality time on my stomach with a flashlight looking for it soon.

I get asked a lot if I intend to upgrade to an alternator. It’s easy enough with just a few pieces from a 1965-’69 engine, but I don’t see the need. I’m not planning to add any electrical demands beyond what already exist and I’ve always had good luck with generators (current situation notwithstanding). In fact, it was the 1983 Cadillac that puked its alternator this winter, leaving us wholly dependent on the Corvair for a couple months.

Once the battery is charging again, other electrical-system projects pending for Ruth include getting the dome light and reversing lamps working; installing a working stock radio (ultimately incorporating an aux input); and potentially relocating the battery to the luggage compartment.

Interior

The Corvair came with a 1979 Michigan license plate incorporated into the front floor and a road sign doing similar duty in the rear. They're both quite effective and I see no reason to remove them. The remaining rust in the floor is entirely cosmetic. Once the weather warms up here a bit more, I'll be treating the rust, encapsulating it, then painting it over with bedliner (I'll do the same thing underneath, but with rubberized undercoating instead of bedliner).

The driver's seat is actually quite comfortable, despite a skin held on by (or mostly composed of) duct tape. A friend sent me a roll of heavy duty 3M tape to use, but the discount-store stuff I've got on there currently is actually holding up quite nicely. Preservation in situ is the plan for now, if for no other reason than it's a good way to keep track of the silver upholstery buttons. I'm told they're irreplaceable. Accessory-style covers, courtesy of my darling wife, are in the offing.

Bells and Whistles

Oversized tires and contemplated lift aside, I don’t wish to deviate too far from the good work the factory did in designing and building the Corvair. Most of my contemplated “improvements” are pretty simple or they come directly from incorporating later-year Corvair parts, allowing everything to be maintained with the appropriate service manual.

I’ve added a smattering of decals (and resisted the urge to add others) and might still get that “Ralph Who?” one I keep threatening. I would really like to add a single foglamp, offset to the passenger’s side, and upgrade the signal lamps to LEDs (which requires a flasher conversion). I will resist, for now, the temptation to add an aircraft landing light for use in passing situations and to counteract the ever-popular LED lightbar found on so many late model 4x4s.

I did change out the incandescent high beams that came on Ruth for a pair of halogen bulbs and have contemplated adding a headlamp relay to get a full 12V to the headlights (currently all current runs through the switch). It's a common mod with Falcons but seemingly not done with Corvairs. I'm already pretty satisfied with the view at night, especially since I added a day/night mirror from a Late Model.

The Forever Car

I have always wanted to keep a car forever. The Camaro wasn’t the one because I’m really just not a muscle-car guy; the ’61 Falcon could have been but I got thrown off by thinking I needed a perfect, rust-free body; the Rambler was already too far gone; and the ’62 Falcon was too heavily modified, having lost much of the charm and simplicity of an early ’60s compact.

I think the Corvair is the keeper, though. It’s happy and lucky, fun to drive and work on, and nearly everything for it is readily available for reasonable money. Maintaining Ruth is rather like keeping a garden, with a little bit to do all the time that pays off in the form of a nice, reliable car. It’s far preferable to the modern-car experience I’ve had, which seems to be mostly about periods of boredom interspersed with catastrophic failures (but hey, those engines and transmissions, they’ll go to 250k ya know…).

Long, long term, who knows what the future holds to keep up with daily driving? I’ve been eyeballing the old 2- and 4-bbl conversion retrofits as a potential basis for some kind of junkyard EFI retrofit. I also follow a really cool electrified ’62 Corvair convertible that’s quite inspirational…

The Motor Underground Chinatown Confidential Episode 2: Street Gassers: Built, Not Bought

In this episode of The Motor Underground, eating, drinking, and walking through the streets of the oldest Chinatown in America starts to pay off in Stoner’s quest to find the mysterious “Underdog” ’56 Chevy Gasser: word starts to spread that he’s poking around and the American Born Chinese who built, raced, and lived their lives in straight-axle Gassers come out of the shadows to reveal their stories. He also finds the hotrodder whose shop put the axles under these cars and gets a nuts-n-bolts lesson on how a gasser was built for the street when everything was built, not bought. Hemmings.com is the ultimate destination for finding your perfect ride. Head to Hemmings.com and register to start your search today.

Pop-up headlights, also referred to as flip-up headlights or hidden headlamps, were prominent features on sports cars from the ’80s and ‘90s. The pop-up headlight feature gave cars more character, making them take on a cartoony human-like appearance when opened and providing a more streamlined look when down and not in use. Pop-up headlights made classic sports cars like the Ferrari F40, Porsche 944, the Toyota MK1 Supra, and Mazda’s MX-5 Miata and RX-7 iconic in today’s car market. So why aren’t automotive manufacturers making vehicles with pop-up headlights anymore?

Are pop-up headlights illegal? That rumor is a common misconception. Pop-up headlights are not illegal, however today’s increased safety standard regulations make it increasingly difficult for manufacturers to offer the feature on new vehicles. As cars began to develop in the 1970s through the 1990s, so did pedestrian safety regulations. The stricter regulations required manufacturers to make the front end of their cars safer for pedestrians. Even though this regulation is put in place for European countries, manufacturers follow the global rules to easily offer their car models in multiple countries.

Due to changing tastes, cost of production, safety standards, and some mechanical issues, automakers ceased to produce cars with pop-up headlights by the 2000s. It’s likely that we may never see new cars with pop-up headlights rolling off of factory lines again, but that gives us an opportunity to appreciate the ones we still have. Check out 11 popular pop-up headlight cars that are currently for sale on Hemmings Marketplace.

The C5 Corvette, a symbol of American automotive prowess, was the last true post-2000s car to feature pop-up headlights. This 2004 Chevrolet Corvette is equipped with a six-speed manual transmission for the driving enthusiast who craves precise control and exhilarating gear changes. According to the classified ad on Hemmings Marketplace, the odometer shows 72,969 miles on the original engine. Finished in a timeless black hue, this iconic sports car commands attention with its muscular stance and aerodynamic contours, hinting at the thrilling experience awaiting behind the wheel.

This 1978 Porsche 924 is offered for sale by the California Automobile Museum and is described as “very clean and sharp looking.” Power is supplied by a 2.0-liter inline-four cylinder engine backed by a four-speed manual transmission. A factory sunroof adds to the style and driving enjoyment while an aftermarket audio system provides entertainment for those longer road trips. Here’s your chance to get behind the wheel of an affordable Porsche sports car.

For an affordable sports car with pop-up headlights, a Mazda Miata is the answer, more specifically a first-generation Mazda MX-5, also known as the Mazda MX-5 NA. Introduced in 1989 and produced until 1997, the pop-up light equipped first-generation Mazda Miata quickly became a best-selling roadster, gaining popularity with its timeless aerodynamic design and agile handling. This example, a 1990 Mazda Miata MX-5, is described as a beautiful unmodified, original sports car with a clean history. Power comes from its stock 1.6L DOHC engine paired to a five-speed manual transmission. The sale includes two keys and manufacturer’s literature.

The 1993 Toyota MR2 is a rare gem that embodies the perfect balance between style, performance, and low-mileage preservation. According to the listing, this particular MR2 has a unique history, having spent its life in the sun-soaked state of California, which has contributed to its exceptional condition. Under the hood, you'll find a spirited 2.2-liter four-cylinder engine, renowned for its reliability and efficiency, mated to a five-speed manual transmission. The exterior of this MR2 is a head-turner, boasting a distinctive Turquoise finish that not only captures the spirit of the 1990s but also stands out in any crowd.

One of BMW’s most iconic sprts cars of all time, the BMW M1, was born from competition, wearing Italian-designed bodywork by Giorgetto Giugiaro and built by German specialty coachbuilder Baur. This rare example is described as being “maintained and preserved to the highest standards.” Over $125,000 was spent to bring this car up to a concours ''preservation-quality'' level. Get the details on Hemmings Marketplace.

The Pontiac Fiero started life not as a sporty car, but as an urban runabout. Where it lacked horsepower, it was still dressed in a sporty guise with a wedge-shaped front end and pop-up headlights that completed its sleek looks when down and not in use. This example from 1987 is equipped with a factory sunroof and its original 2.8-Liter V6 with 41,000 original miles. It exhales through a performance dual exhaust. According to the classified ad on Hemmings Marketplace, the Fiero has a clean CarFax history, great service records, and comes will all book and manuals and a custom car cover. The seller states that it “runs and looks great.”

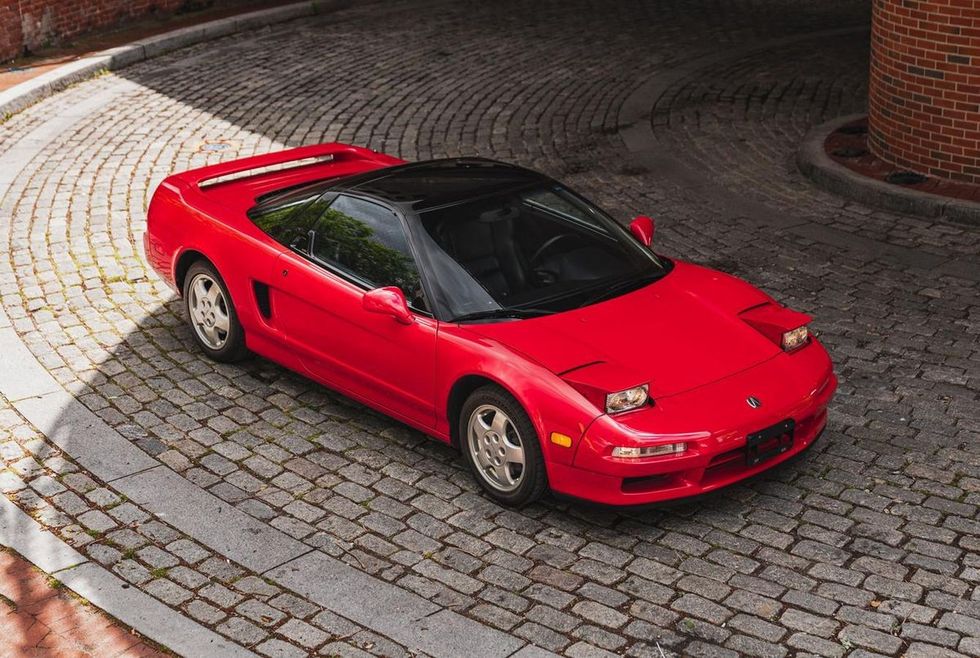

Short for “New” “Sportscar” “eXperimental”, the Acura NSX was an instant sports car marvel upon its release. It was created by Honda to rival the performance of V8-equipped Ferraris and was the first ever mass-produced car to sport an all-aluminum body.

The first generation NSX was produced from 1990 to 2005. This particular example, Chassis # JH4NA1159NT000781, is an early pop-up headlights model equipped with a five-speed manual transmission and the 270 horsepower 3.0-Liter V6. It’s hard to resist the aerodynamics and styling, which was inspired by an F-16 fighter jet cockpit.

The Opel GT, often referred to as a scaled down Corvette or "European Corvette," is a charming and nimble classic sports car that combined the look and feel of a sports car with more economical pricing. Today, the timeless design has earned the Opel GT a cult following. This example, a 1973 Opel GT, was reportedly stripped to a bare shell and repainted in Oxide Gray Metallic. The seller states that the “engine was professionally rebuilt to a 2.0 at a speed shop” and the car is “ready to be driven and has drawn a lot of attention at car shows.” It took six years to complete the project. Check it out here.

Introduced in 1975, the glamorous 308 GTB, designed by Pininfarina and built by Scaglietti, was the first Ferrari road car with a fiberglass—or “Vetroresina”—body. Only 712 such models were built before production was switched to steel panels, adding over 300 pounds to the car’s curb weight. Tipping the scales at a relatively light 2,315 pounds, the aerodynamic and well-balanced Vetroresina 308s have become an increasingly attractive choice for Ferrari enthusiasts looking for responsive performance and agile road-handling capabilities.

This car is accompanied by a tool roll, an owner’s manual, a service booklet, and a protective leather wallet. This rare, lightweight 308 GTB presents an excellent opportunity to add a spirited prancing horse to your stable.

A predecessor to the Lamborghini Countach and successor of the Lamborghini Murcielago, just 346 Diablo SV models were produced between 1995 and 1999. This example, offered by August Motorcars, is finished in stunning Giallo Evros over Nero SV Leather interior and features the incredible dual roof scoop that gives this Diablo SV a road presence unlike anything else. A must-see for enthusiasts and collectors alike, the seller writes, “this Diablo SV comes to us in beautiful condition with no accidents, has been fully detailed, and passes our stringent 100 point inspection making it August Certified.”

The first generation RX-7 was introduced with retractable headlights, but it was the third generation RX7 model’s pop-up headlights that cemented themselves in pop culture. This 1993 Mazda RX7’s sleek styling is the cherry on top of its sequential twin-turbocharged rotary engine and agile handling. According to the seller, this three-owner RX-7 has been cherished from new and it has covered only 40,259 miles. It is described as “brilliantly original” and an “investment-grade example that you can drive or show with pride.”