Mind Defined

There are four different meanings of mind.

Posted Jan 21, 2021

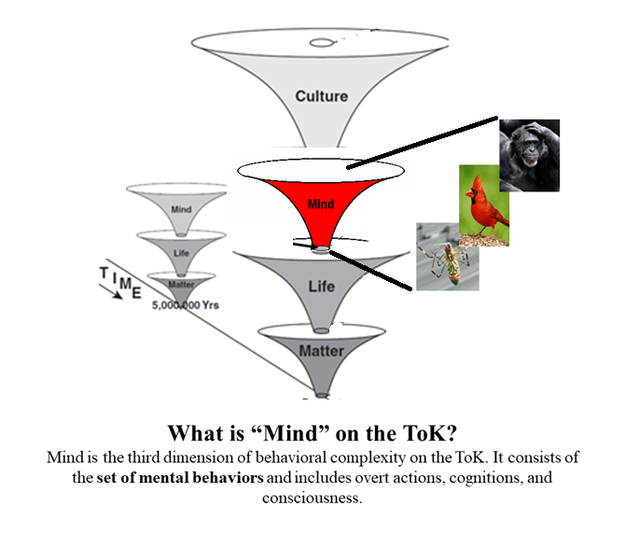

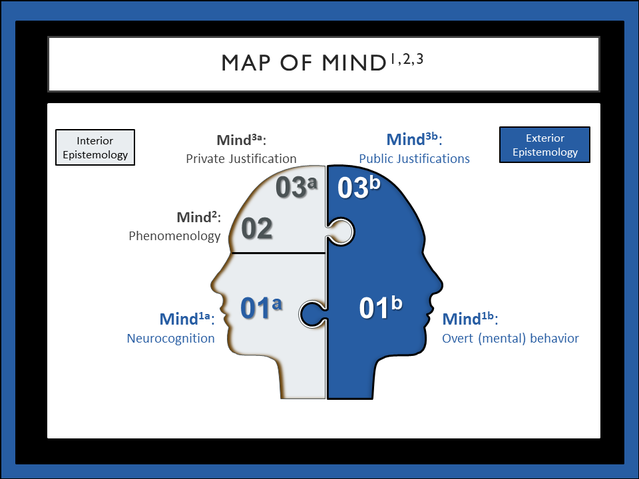

One of the great challenges of the Enlightenment was the proper way to define mind in relationship to matter. The Tree of Knowledge System allows us to unlock this puzzle and effectively define mind. There are four distinct meanings.

First, there is mind as behavior; however, not just any behavior. Rather, mind as mental behavior. Think of two cats, one dead, one alive, and both are falling out of a tree. One lands on the grass and bounces. That is physical behavior. The other lands on its feet and takes off. That is mental behavior. Mind on the ToK System is the set of mental behaviors. Overt actions like this are identified as the domain of “Mind1b” on the Map of Mind1,2,3.

Second, there is mind as neurocognition. This is Steven Pinker's meaning in How the Mind Works. The 'neuro' here references the brain and nervous system. Cognition means information processing defined in terms of (a) the process of inputs, computational recursion, and outputs (see, e.g., here), (b) information theoretic views regarding prediction/uncertainty (see, e.g., Karl Friston’s free energy work), and (c) schemas and semantic meaning making (see, e.g., semiotics). This is the domain of Mind1a on the Map of Mind1,2,3. John Vervaeke’s 4P/3R metatheory of cognition finally helps us see what functional information processing actually means (i.e., recursive relevance realization) and how to relates it to cognition as knowing (see here).

Third, there is mind as subjective conscious experience, which is the domain of Mind2 on the Map of Mind1,2,3. Sometimes called phenomenology, this is the first-person experience of being that emerges out of neurocognition at some point in the animal kingdom (see here for a recent analysis). It is what David Chalmers calls the hard problem. (Note: Mind1 represents what Chalmers calls the easy problems). There are actually two distinct aspects that make subjective experience hard. First, there is the ontological aspect—it remains scientifically unclear exactly what kinds of brain activity are necessary for subjective experience and why. However, progress is definitely is being made on many fronts (see here for recent work on human consciousness). Second, there is the epistemological aspect. Subjective conscious experience is a kind of epistemological portal, such that it can only be seen from the inside. Thus, science, with its third-person commitments, has major epistemological blind spots when it comes to pure subjectivity. Given that science is currently our dominant form of knowing, this has led to many confusions. For example, it relates deeply to the problem of psychology.

Fourth, there is mind as self-conscious justification. This is the domain of humans as persons, language, reason giving, and human culture. This is the referent in works like Richard Tarnas' The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View. It is Mind3a,b on the Map of Mind1,2,3. The various domains connect via the concept of informational interface. The structure and function of Mind3 and how it operates on the Culture-Person Plane of existence was revealed by Justification Systems Theory, which was the key insight in 1996 that ultimately led to the Unified Theory of Knowledge.

The first Enlightenment was deeply confused about mind, and its relationship to both science and the natural and social worlds. It is time for us to mature into a proper conception. Maybe it will help us become conscious so that we can evolve into a second Enlightenment.