Summary

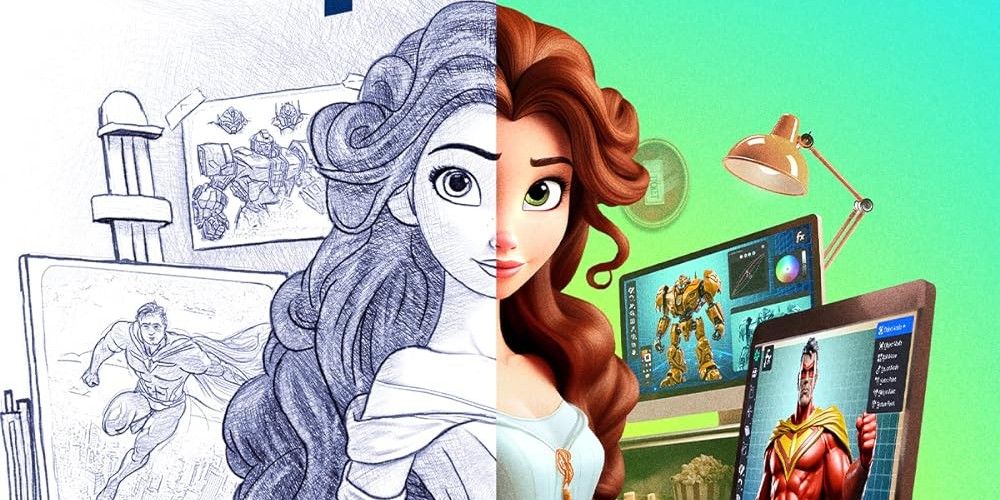

- Pencils vs. Pixels examines the evolution of animation from 2D to 3D, showcasing the Disney Renaissance era and the impact of technological advancements.

- John Pomeroy discusses his history as a Disney animator and the impact of this industry shift.

- Narrated by Ming-Na Wen, the documentary includes interviews with industry professionals like Seth MacFarlane and Kevin Smith, providing unique perspectives on the animation medium.

Pencils vs. Pixels examines the evolution of animation by looking back at the height of 2D animation, including the Disney Renaissance era in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The documentary also shows how the animation medium changed with technological advancements introducing 3D computer-generated animation. This forever changed the animation industry and medium, although it also delves into how 2D animation is still popular among fans and animators in movies like Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse, combining multiple animation styles.

Pencils vs. Pixels is narrated by Ming-Na Wen. Numerous industry professionals and giants in animation, including Seth MacFarlane, Kevin Smith, Alex Hirsch, Peter Docter, Bruce W. Smith, and John Poweroy, also share their stories and perspectives in the documentary. Pencils vs. Pixels is co-directed by Phil Earnest and Bay Dariz, with Dariz wearing multiple hats as writer and producer as well.

Why Disney Doesn’t Make 2D Animated Movies Any More

The Lion King remake and Frozen 2 both highlight how Disney no longer makes 2D animated movies like so many of their classics, but why is that?

Screen Rant interviewed animation legend John Pomeroy about the new documentary Pencils vs. Pixels. He explained how he became involved in animation and how the shift away from 2D animation impacted the industry. Pomeroy also reminisced about his time working with Eric Larson and other Disney legends back when he first began working at Disney and shared a conversation he had with one of the animation team members who worked on Wish.

John Pomeroy Talks Pencils vs. Pixels

Screen Rant: John, first of all, it is an honor to meet you. You're an animation legend, and you had a hand in shaping my childhood. American Tail was, I think, the first film I ever saw in a theater.

John Pomeroy: Wow.

Yeah. You also did All Dogs Go to Heaven, The Land Before Time. So much of my childhood, so thank you. What was the first animated project that sparked your interest in animation?

John Pomeroy: Well, let's see. The first thing I did professionally was Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too. That was my first animation back in 1973. And up to that point, I did one little test that I posted on Instagram of Mickey Mouse from Sorcerer's Apprentice. I did that when I was about 13, 14 years old. What's interesting, Joe, is that early in my passion for animation, I wanted to be a background artist, not an animator.

And so the transition happened after they accepted my third portfolio back in '73 and they said, "You'll be a better animator if you understand the principles of animation." I said, "Hey, I'll do anything you guys want me to do as long as I end up in the background department." And so they put me under the tutelage of nine old man, Eric Larson.

I learned all the basic principles from him. I was an animation trainee under his tutelage for about four months, and my first test I did with him was awful, but I saw it on his Moviola and he's like scratching his chins. "It's not too bad." And I'm going, "This is awful." But something happened. I saw that test and I saw the potential of that art form. I thought to myself, "It's like being God, you're creating something from nothing." And I got bit by the bug, threw away the paintbrushes, became an animator.

Eric Larson is one of the Nine Old Men. He's an absolute legend in the animation industry. Can you talk about your experience working with him, and what did he teach you that you're still using today? Is that test you're talking about the pencil test in Pencils vs. Pixels?

John Pomeroy: I think so. It was a frog test, a magician frog with a little turtle assistant. I think that's the one I'm talking about. It was about... I don't know, maybe around a 40- or 50-foot test. Working with Eric, he was probably, out of the nine key animators, was probably the most ideal for teaching this new wave of animators that was coming in. And he was extremely patient. He was extremely kind. I remember Andy Gaskell and I would have rubber band fights through his office while he was critiquing another student's work.

And he would just snicker and laugh. He loved it because, I think to him and to a lot of the other nine old men and the old timers, it was revisiting their own start in the '30s during the Depression era, when they started out as young college graduates in their early 20s, they're watching this happen all over again, and he was extremely kind.

He taught me the technique of drawing from the shoulder, which I use to this day. He would draw very delicately. He would hold a pencil like this with his pinky as this outrigger balance element, and his hand would just slide over the paper, and he said, "Oh, yeah. Years ago, Bill Teitler told me about drawing from the shoulder, and I've been doing it ever since." So I picked up on that and started drawing that way myself. And it's just something that stuck with me all the time. And believe it or not, you can't see it, but the desk I'm using right here is an old Kem Weber desk from the old Disney Days. It still has the old Disney Studios label in it. This was Harry Holt's desk. He was Eric Larson's assistant back during the '40s and '50s.

You have a piece of Disney history right there in your office. That's crazy. Now, the one thing I love about Pencils vs Pixels, it really gives you a broad scope of the history of animation. As Disney celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Can you talk about how the nine old men's influences is still felt today in current animation?

John Pomeroy: Yeah. We got in that conversation last night, the woman who is the supervising animator for Wish, Kara. She was visiting here on campus to give a couple of days lectures as guests of Lipscomb University. We got into a conversation about that, and I said, "There was a great migration that happened." And all the table looked at me and said, "What do you mean?" I said, "Well, when Michael Eisner decided that 2D animation wasn't profitable anymore, he systematically closed Disney Orlando and Florida, Disney Paris and France, and then finally Disney Burbank."

So guys like me in 2003, we were all out of work, but all of these unemployed artists made migrations across the United States into college and university art departments and began animation departments. So all of those lessons, those 12 illusion of life principles got passed on to generation after generation of students.

I've been at Lipscomb for eight years now, and I've been teaching those same principles to wave after wave of students. They don't want to learn about anything else. They want to learn about hand-drawn 2D animation. So I think it's important because of the preservation of that art form, the way it was invented back in the '20s and '30s by Walt Disney in his studio.

I think the documentary does a really good job of telling the story of that shift in the early 2000s from 2D hand-drawn animation to the 3D animation. Did you immediately feel that shift when the box office numbers started rolling in, or was there more of a split where people thought, "These are two different?"

John Pomeroy: Yeah, there's plenty of stories to go around for both mediums, but yeah, I started to feel it a little bit right after Atlantis: The Lost Empire, because the projected numbers weren't quite performing where they were hoping. And so there was a steady decline once we hit... I think Lion King, Pocahontas did well, and then Atlantis, Treasure Planet, and Home on the Range, and Brother Bear, there was a slow decline in profitability.

Now, Michael Eisner, had many strengths, but being an innovator and the type of mind that Walt was, was not one of them, and so he saw a need to close it down. This was 15 years before when he and Frank Wells first took over. They were thinking that, "Okay, this medium needs to be realigned or closed. It's not making that much profit."

But I think Roy Disney was instrumental in bringing more talent in that a new wave and a renaissance happened during the late '80s and through the '90s. But I just think it was shortsightedness on their part and I think they eventually regretted doing that. I think they would like to keep 2D since they are the founding fathers of 2D animation. So yeah, that's where we are today.

Yeah. I feel like we're in this resurgence of 2D animation, especially with all these streaming sites that are coming out now. I just really recently watched a fantastic 2D animation called Blue Eye Samurai on Netflix, and a lot of these other studios from around the world are now really embracing 2D animation. Where do you see the future of animation going?

John Pomeroy: Well, with technology, the way it exists right now, the entire world is one gigantic studio, Joe. So I can work easily with Sergio Pablos in Madrid and Spain. Working on Klaus, working in Canada, working in Mexico, working in China like I'm doing right now. The whole world is accessible. So the community of artists is still thriving for 2D animation. We just need the power stories that come up to bat and deliver the goods to make it profitable, because it's all based on dollars and cents.

The major studios, the major players that distribute these, they want to see the players come out and deliver the $300 million profitability that first box-office weekend. This was interesting because it brings up a story about, "When you were a child you saw An American Tail." American Tail was one of the first films to go out there and make 2D hand-drawn animation legitimate to all the other studios.

Up until that time, I think Great Mouse Detective came out, and they did okay. They did like 30 or $40 million. American Tail came out and did 65, and suddenly Fox, Warner Brothers, Universal. All the studios now took notice. "Oh, my gosh, we got to jump into this." So that scenario has to play out. Once again, money is what drives the medium.

This is a bit of a fanboy question for me. I know that in 1973, Winnie the Pooh was one of the first characters you worked on, but who was the first character you drew at Disney, and who was your favorite character to draw from Disney?

John Pomeroy: Ooh, let's see. I was doing a Tinker Bell test with Eric, long test of Tinker Bell falling in love with a little soldier that comes out of a cuckoo clock. And I had this epic that I was doing, and I would've continued on that had it not been for the fact that I got called into a meeting with Woolie Reitherman and Frank Thomas.

Woolie sucking on his big cigar, says, "Well, we think you're doing great. We love your work. We think you're ready for something a little more challenging. This is Frank Thomas. I know you've met him. We would like to get you started on a chunk of about 120 feet at the end of Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too. So that got me rolling, but Tinker Bell, I fell in love with her. The Marc Davis treatment of Tinker Bell and Peter Pan, I just loved. I would've loved to have finished that personal test, but I didn't get a chance.

About Pencils vs. Pixels

Pencils vs. Pixels is a celebration of the unique magic of 2D hand-drawn animation and an exploration of how the Disney Renaissance of the late 1980s and early 1990s led to an animation boom that was quickly upended by the computer animation revolution that followed. Narrated by Ming-Na Wen, Pencils vs. Pixels features many of the legendary artists who brought these now-classic films to life as they guide us through the last few decades of animation and into the future that's yet to come.

Pencils vs. Pixels is now available on VOD platforms.