The Vita Caroli Quarti of Charles IV (1316 – 1378) is one of the earliest royal autobiographies written. A new edition with a German translation is recently published as part of the 700-year anniversary of his birth.

Die Autobiographie Karls IV. Vita Caroli Quarti.

Einführung, ûbersetzung und Kommentar von Eugen Hillenbrand. Herausgegeben von Wolfgang F. Stammler.

In: Bibliothek Historischer Denkwürdigkeiten.

Alcorde Verlag 2016

ISBN 978-3-939973-66-9

Review

In 1350 Charles IV of Bohemia fell seriously ill with an inflammation in the central nerve system causing widespread paralysis. It is generally believed that he spent his time in bed dictating a biography of his first 34 years. Although posing a number of challenges for the modern reader, it is a unique work detailing – at least partly – the mentality and worldview of a highly accomplished medieval ruler (he later went on to be crowned king of Germany, Lombardy and Burgundy as well as Holy Roman Emperor.)

Written in Latin, it is preserved in twelve manuscripts. Already in the later Middle Ages it was translated into Czech and German and In 1585 it was printed for the first time. Since 1979 it has been published and edited four times together with modern translations into Czech, German, English and French.

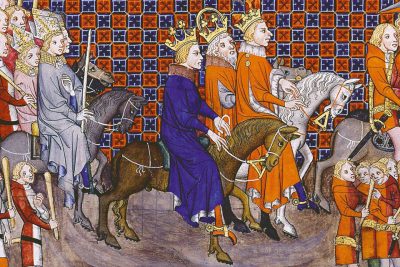

This year – the 700-year anniversary of his birth – a re-edition of the translation into German from 1979 by Eugen Hillenbrand has been prepared together with a new edition of the introduction bringing it up to date. The edition has also been provided with a number of illustrations, many of which will help the reader towards a better understanding of this peculiar work; especially interesting are the included miniatures, which graces the Czech Manuscript from 1472 (Wien, Nationalbibliothek Cod. 2618)

Autobiography or Mirror for Princes?

It is an odd text. On one hand it contains a number of chapters written or dictated in the first pronoun, I. On the other hand, chapters 15 – 20 are written with Charles IV as the main character but with the use of the third pronoun). Parts of these chapters seem to be written in the traditional form of a chronicle. Secondly, it contains a number of religiously inspired chapters, which might best be understood as sermons – or sermon-inspired texts.

It is an odd text. On one hand it contains a number of chapters written or dictated in the first pronoun, I. On the other hand, chapters 15 – 20 are written with Charles IV as the main character but with the use of the third pronoun). Parts of these chapters seem to be written in the traditional form of a chronicle. Secondly, it contains a number of religiously inspired chapters, which might best be understood as sermons – or sermon-inspired texts.

It is probable – and Hillenbrand argues well for this understanding – that Charles dictated his thoughts and memoirs while he was lying ill in Prague in1350. When he got better, he had one of his scribes finish the work. It ends with 1346, when he was elected King of Germany.

As such, the autobiography was dictated as part of what was obviously a personal testament to the justification of his rule; contested as it was inside a constant warring and feuding Central Europe. Part of this justification was the sense of his fate as heavenly decided; hence the parts of the autobiography, which delineates the proper form of a religiously inspired rule characterised by wisdom and godliness. The “new” literary element, is that Charles chose in his own autobiography to recount his personal fate and life as the proper exemplum of how a godly ruler should behave. This was the legacy, he wished to impart to his heirs

First of all, it is obvious from this autobiography that he believed his justification to grab and hold fast to royal (and later imperial) dominion was his ancestral heritage. He became de facto leader and later king of Bohema, because he was (through his mother) a direct descendant of the the Přemyslids, the ancient Bohemian royal dynasty. As he writes: “As the community of the good men of Bohemia recognised, we [his kin] were descendants of the ancient Bohemian royal dynasty, they loved us and offered their help, in order that we might regain the castles and the royal desmesnes” [p. 150 – 51: my translation].

Secondly, however, his success depended on the Grace of God (gratia Dei). As witnessed by miracles and foreboding dreams, God was directly holding his hand over Charles, protecting him from the onslaught of devious and evil oath-breakers and conspirators; such as Easter 1331, when his entourage was poisoned at breakfast and he only escaped, because he did not eat before communion (120 – 121). To be a just ruler meant to keep faith and uphold a virtuous lifestyle, avoiding committing deadly sins like pride, lust, envy, and wrath. As his main model, he referred to David. Elsewhere, tells Hillenbrand, he expressed his lineage as reaching back to the days of the prophets.

It is through this prism, Charles IV offers us a fascinating account of how he powered by his royal ancestry and God’s favouritism was able to “at great cost and much effort” regain and rebuilt the castles, necessary to continue in power. As such, the autobiographical chapters contain seemingly endless stories of “guerra” – feuding, warring and besieging in Germany, Bohemia, Tyrol and Italy. To put it plainly, he was obviously early on a seasoned warrior, who exuded military prowess in the medieval art of carrying arms and armour from he was 15 years old. He was also a skilled negotiator, personally mastering five languages both in reading, writing and speaking (French, Czech, Latin, Italian and German).

Czech? German? European?

Charles continued in his lifetime to amass royal titles as King of the Romans (Germany), Bohemia, Italy and Burgundy. In 1355, he was crowned Emperor in St. Peter’s in Rome. Soon after, he had made his mark on later European history by publishing the Golden Bull in 1356, which for more than 400 years constituted the set of rules regulating the election of the king of the Romans (and thus the Holy Roman Emperor).

He also became known for his patronage of culture and arts in Prague and Nuremberg. As such, the Czechs came to know him as Pater Patrae, a title, which he was presented with at his funeral in Prague in 1378.

It stands to reason, however, that historians of different ilk and nationality, have tried from time to time to appropriate him as something else: with Luxemburgish ancestry through his father, his personal relations with the noble houses of most of most of Western and Central Europe and his collections of royal titles, he has in the second half of the 20th century continuously been cast as the Proto-European Prince par excellence.

One of the fascinating essays, which the new edition holds, is a sketch of the different histories, which have been floating since the anniversary of his death in 1978, which was celebrated with great exhibitions in Köln, Prague and Nuremberg. More or less, all of these tried to peddle the idea that Karl was ruler of Europe. Nevertheless, French and English historians – as opposed to their German colleagues – held back. For them, he was but one amongst many local rulers in the 14th century. Such was the case until Pierre Monnet and Jean-Claude Schmitt – both heirs of the Annales tradition in France – published the Manuel d’histoire franco-allemand in both French and German. For them (and Hillenbrand) Charles was seen to regard Europe as his political scene; par excellence witnessed by the staging of his spectacular coronations in Bonn, Prague, Aachen and later in Rome, but also in the conduction of Christmas celebrations and other such liturgical celebrations.

In the 14th century, crowns mattered. This is obvious from the linkage between the vigorous way in which Charles IV endeavoured to lay his hands on the royal insignia of the Holy Roman Kings and Emperors and the fact that he subsequently linked its visual political programme with his own understanding thereof as he presented in the introduction to his autobiography.

Another detail, though, which Charles did not allude to, is the fact that the imperial crown held – as opposed to its royal cousins – an arch. To be Holy Roman Emperor was to be invested with an overarching role uniting European realms of a lesser status. It is without doubt the French king took great care not to acknowledge this supremacy of Charles, when he visited France one last time a few months before his death. At this visit, Charles was staged not as emperor, but as family.

It is obvious from this and many other historical writing that the legacy of Charles was not just one of the first royal autobiographies, we possess. He was also a gifted politician, writer, and a remarkable patron of culture and art as witnessed by the mark he set upon Prague. However, judging from his autobiography – and reading it in connection with other moral treatises of his time, we do not perhaps get quite this feeling of a European prince. Rather, he comes out as a gifted warrior good at fighting his way through petty political skirmishes and out of nasty military exploits. But then, this is perhaps also much more interesting…

This is a very fine edition in the best of the fastidious German tradition. With its timely publication, it also serves to make the text available once more for a wider public. Unfortunately, the English Edition from 2001 is currently out of print (and also very expensive). The present edition helps to fill this gap; not least since it provides not just the German translation, but also the Latin text together with fine notes and a (nearly) up-to-date bibliography. Even though the edition is in German it is heartily recommended to be used in teaching contexts. The Latin is not at all complicated to read and might inspire students to feel accomplished when confronted with the original text. Highly recommended.

Karen Schousboe

FEATURED PHOTO:

Portrait of Charles IV in the Johann Očko von Vlašim Retable. Foto: Nationalgalerie Prag