- Self Made: The Story of Madam C.J. Walker dropped on Netflix on Friday, March 20.

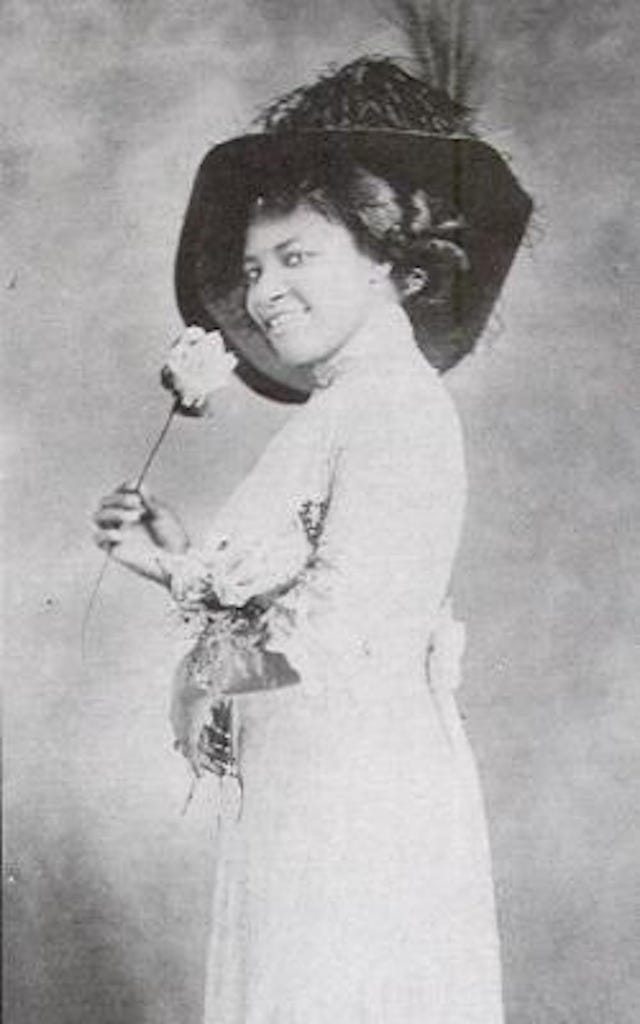

- The four-part mini-series tells the story of how Madam C.J. Walker (Octavia Spencer) built a beauty empire that specialized in Black women's hair.

- Here's what you need to know about A'Lelia Walker (Tiffany Haddish), Sarah Walker's daughter.

Premiering on Netflix on Friday, March 20, Self Made: The Story of Madam C.J. Walker tells the extraordinary story of the America's first woman millionaire. Sarah Walker, better known as Madam C.J. Walker, built a multi-million dollar beauty company that catered to Black women, alongside her daughter, A'Lelia.

Pivoting from her comedic roles, Tiffany Haddish plays A'Lelia, Sarah's only child. Haddish brings her characteristic charm and humor to the part, so that the character sparkles.

Spanning 1906 to 1919, Self Made condenses Walker's career into four hours, from her days as a saleswoman to her decision to launch her own business. Due to the narrow focus, the show inevitably leaves out some of the most fascinating parts of A'Lelia's life.

For example, did you know that A'Lelia Walker was close friends with luminaries and writers like Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen? That she started a literary society out of her apartment? That she arranged a $42,000 wedding for her daughter in 1923—or the equivalent to $600,o000 today? You wouldn't by simply watching Self Made.

Frankly, there's enough about A'Lelia to merit her own mini-series. A'Lelia's granddaughter, A'Lelia Bundles, wrote the Madame C.J. Walker biography that inspired Self Made, and she's working on a book about A'Lelia. Take note, Netflix! A'Lelia's up next.

Here's what Self Made leaves out about A'Lelia.

She probably wasn't a lesbian.

In the show, A'Lelia is in a relationship with a woman named Esther, which causes tension between her and her mother. However, her granddaughter and biographer, A'Lelia Bundles, attests that Esther is a fictional character. "What is portrayed in the series is certainly not something that really happened. And it certainly wasn't a source of conflict with the mother," Bundles tells OprahMag.com.

Self Made is definitive about A'Lelia's sexual orientation, but the truth about her dating history is hazier—simply due to a lack of documentation. While writing A'Lelia's biography, Bundles is struggling with that very void.

"I don't have any letters. I don't have any documentation. I don't have anything that can tell me definitively. So I'm trying to work with what I know with circumstantial evidence," Bundles says.

Still, Bundles has found evidence that A'Lelia dated a woman after her third marriage. "Her last relationship after the failed third marriage may have been with a woman. A person who was a longtime friend of hers," Bundles says.

However, we do know this about A'Lelia: She was an ally to the LGBTQ+ community. "She had many friends who were queer. She was comfortable, they were very comfortable in her home," Bundles says.

She was married and divorced three times.

Self Made portrays A'Lelia's first marriage to John Robinson (J. Alphonse Nicholson), which lasted from 1911 to 1914. She remarried Dr. Wiley Wilson in 1919, and Dr. James Arthur Kennedy in 1926. She divorced Kennedy shortly before her death in 1931.

She adopted a daughter named Mae.

In 1913, A'Lelia adopted a young woman named Fairy Mae Bryant, then about 15. That same year, the three Walker women relocated to Harlem.

Ten years later, A’Lelia arranged her daughter’s marriage to Dr. Gordon H. Jackson, the son of a wealthy Cincinnati gold dealer. According to Bundles's research, the wedding was "Harlem’s social event of the season and of the year." Over 9,000 people gathered at the Walker's Irvington-on-Hudson mansion, called Villa Lewaro, to partake in the expensive festivities. The wedding cost $42,000, which is about $600,000 today.

However, Mae's marriage soon frayed. A year later, after the birth of their son, the couple divorced. After four years, Mae married again—this time, for love. When A'Lelia died in 1931, Mae took over the Walker cosmetics company, which she ran until her death in 1945.

She started a literary salon called the Dark Tower.

After moving to New York, the Walker women completely renovated two adjacent brownstones on West 136th street, turning them into a complex that both housed the Walker Beauty Parlor, College and Spa and their private residences.

The Walkers later moved to Villa Lewaro, an estate in the Hudson Valley, but maintained their lavish apartment–and in 1927, A'Lelia gave it a second life as the heart of Harlem Renaissance's social scene.

Named for a Countee Cullen poem, the Dark Tower was a society designed to foster young Black creatives. “We dedicate this tower to the aesthetes. That cultural group of young Negro writers, sculptors, painters, music artists, composer and their friends," the Dark Tower announcement read. "A quiet place of particular charm. A rendezvous where they may feel at home to partake of a little tidbit amid pleasant, interesting atmosphere. Members only and those whom they wish to bring will be accepted.”

Located in Walker's apartment, the Dark Tower was open between the hours of 9 and 2 a.m., cost a dollar a year for membership, and was bustling.

“These parties had all the artists, musicians, writers, actors who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, but it was also the newspaper publishers, the Civil Rights leaders—everybody, at some point,” Bundles told Saving Places. “It was very much a central location for the Harlem Renaissance.”

The Dark Tower only existed for a year, but A'Lelia kept throwing parties.

Langston Hughes called her the "Joy Goddess of Harlem's 1920s."

A'Lelia was known for her vibrant gatherings held at Villa Lewaro, the Dark Tower, and her private residence at 80 Edgecombe Avenue in Manhattan. Poet Langston Hughes, a frequent guest, called her the "Joy Goddess of Harlem's 1920s."

“She would usually issue several hundred invitations to each party. Unless you went early there was no possible way of getting in. Her parties were as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour—entrance, lobby, steps, hallway, and apartment a milling crush of guests, with everybody seeming to enjoy the crowding,” Hughes recalled in his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea.

After her death, Hughes wrote a poem about her.

Walker passed away in Long Branch, New Jersey in 1931. More than 11,000 people visited Howell’s Funeral Home in Harlem to pay respects to Walker, and 1,000 gathered for an invitation-only funeral.

One of the attendees was Langston Hughes, Walker's good friend. He wrote a poem to commemorate his death, which he read at her funeral.

She did not die at home

In her own bed at night.

She died where laughter was,

And music, and gay delight.

She died as she had lived

With no wearying pain

Binding her to life

Like a hateful chain;

So all who love laughter

And joy and light,

Let your prayers be as roses

For this queen of the night.

Let your prayers be as roses

And your songs be as sun

To kiss the last road

Of this lovely one—

For now—all tomorrow

And eternity’s great years—

She shall live in her laughter

And not need our tears.

Her death had a major impact on her community. “A’Lelia’s death marked a significant shift in the tone and temper of the social, political, and artistic life in Harlem,” wrote Mary Schmidt Campbell in her book The American Odyssey. Hughes agreed, saying A'Lelia's death marked the “end of the gay times...in Harlem" during his eulogy.

For more ways to live your best life plus all things Oprah, sign up for our newsletter!