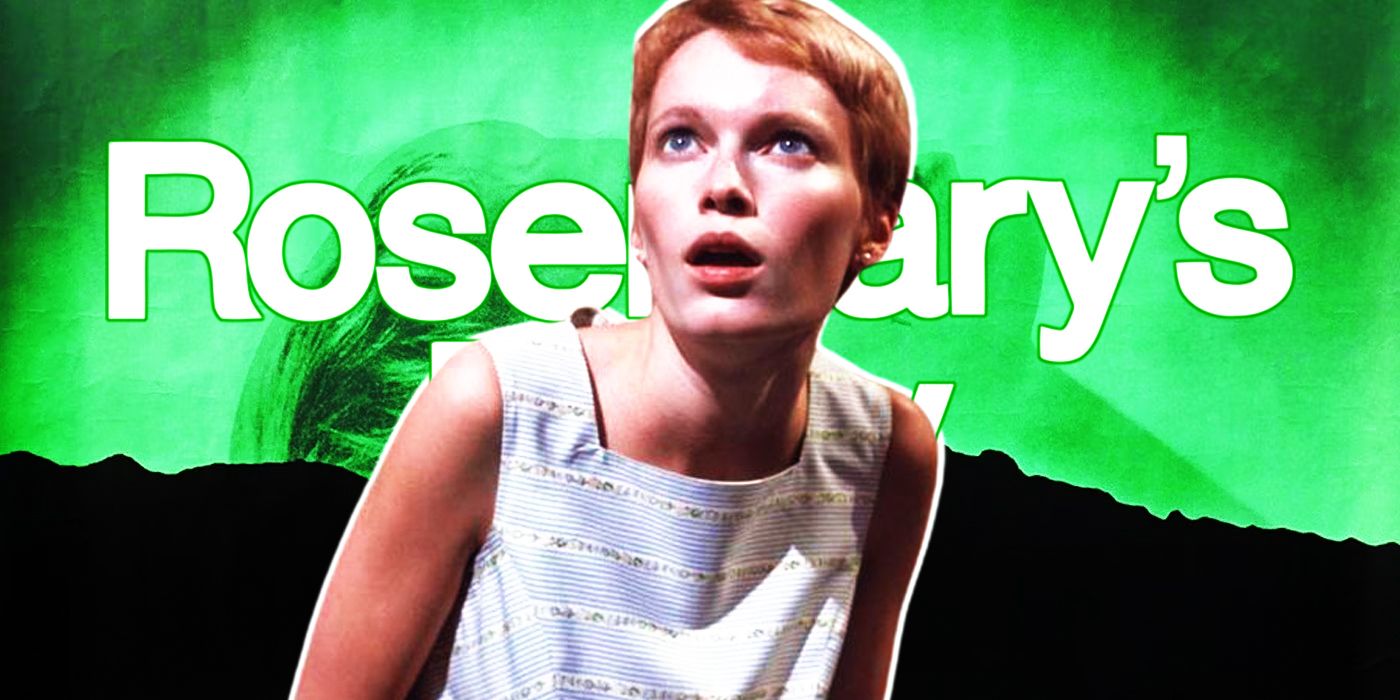

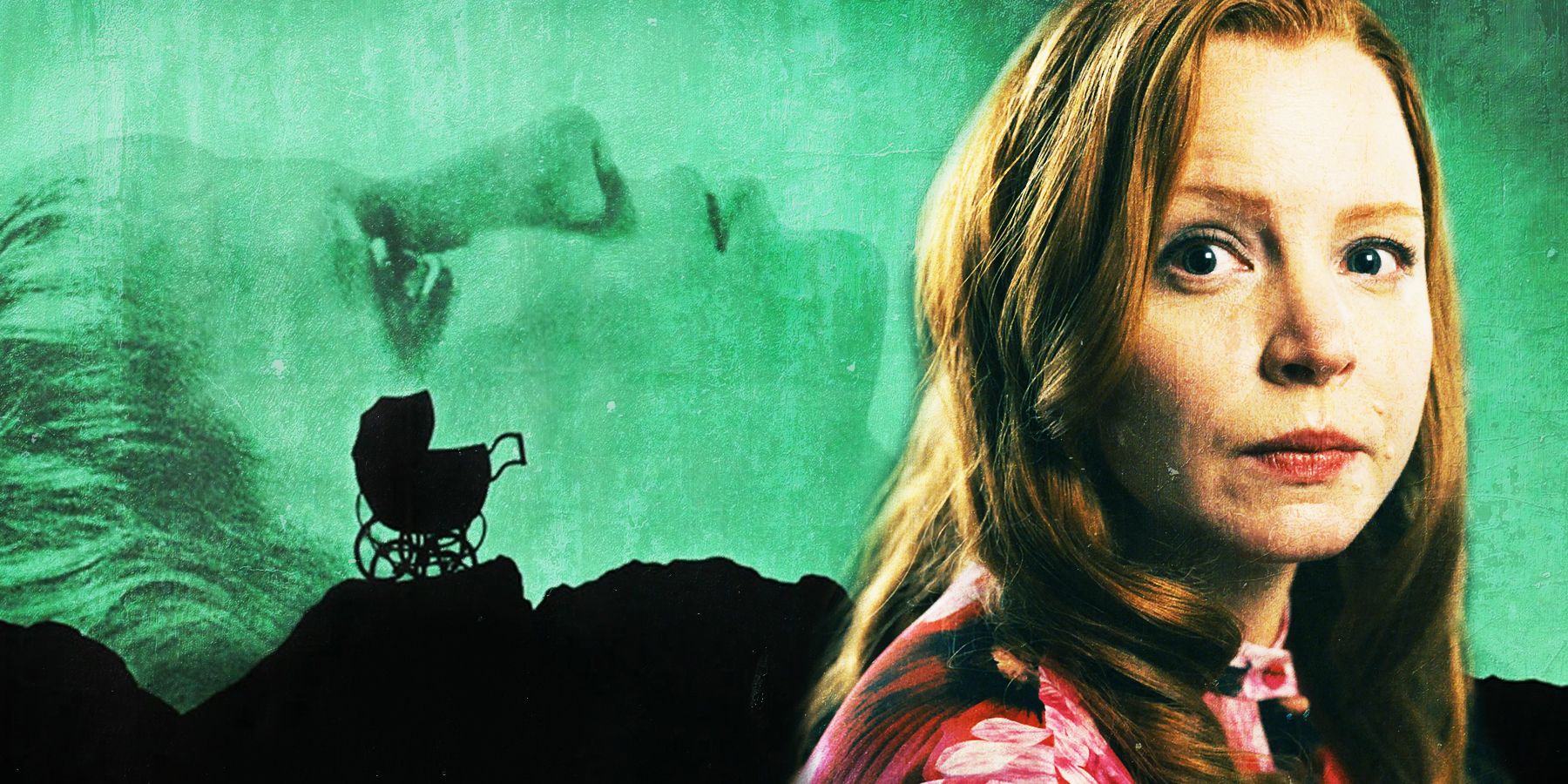

In the decades after its release, Rosemary's Baby became ubiquitous. It's now considered a classic whose appeal extends even beyond ardent horror fans and film critics. Beneath its Satanic themes, the film touched cultural nerves that were exposed during the 60s. That said, its subject is anything but archaic. Recently and unfortunately, Rosemary's Baby's fear of religion and mistrust of older generations only gained more relevance in the decades after its release, effectively making it timeless.

The year is one. Or, in other words, 1966. Rosemary Woodhouse and her new husband, Guy Woodhouse, moved into their new apartment in the magnificent but creepy complex known as The Bramford. They live next to the very friendly but pushy Castavets, who quickly (and forcibly) ingratiate themselves into Guy's good graces. Rosemary is expecting her first child. Things should be perfect, but they aren't.

Guy is increasingly manipulative and dismissive. People are mysteriously going blind or dropping dead. The Castavets are a little too invested in the unborn baby. And don't get Rosemary started on the baby's conception, or the scarily real dream she had in the process. All things point to a Satanic conspiracy to steal her baby for some nefarious goal, but what is a girl in the oppressive world of the 60s to do? Who will believe her, and who can she trust? Most importantly, can Rosemary even trust herself?

This is the premise of Rosemary's Baby, directed by the controversial filmmaker Roman Polanski, released in theaters in June 1968 and based on the 1967 novel of the same name. It stares. Mia Farrow, John Cassavetes, Sidney Blackmer and Ruth Gordon.

Rosemary's Baby Is Body & Psychological Horror Done Right

Rosemary's Baby used Satanism and cults as metaphors for oppression and generational warfare -- and it still works today

RETRO REVIEW: The Omen (1976) Retains Its Classic Status, but Shouldn’t Be Considered Sacred

The Omen is a classic of the religious horror subgenre that introduced many iconic quotes and tropes, but it it's anything but perfect.While it's easy, appropriate and necessary to criticize Polanski as a person, it's harder to question or deny his capacity as a director. This was at least the case for Rosemary's Baby, which he made when he was at the top of his game. His adaptation of the novel is one of the best films of the 60s, and cinema in general. Rosemary's Baby boasts beautiful visuals, strong and memorable costumes, a tight screenplay with memorable quotes, a strong story, a good soundtrack, a great cast and excellent presentation that all stood the test of time.

Even those unfamiliar with it are no doubt aware of its influence and legacy, especially among the succeeding films that benefited from following its footsteps. Despite being extremely timely for its 1968 release, it endured against all odds. The movie works both as a period piece and as transcendental cinema. However, one cannot discuss the power of Rosemary's Baby without first discussing the era from which it came, and the context of its place in pop culture at the time of its release.

In the 60s, conservative tradition was eroding around the world. This was very much the case in the United States, where religion played a vital role in many people's lives. These people fearfully watched as secularism rose concurrent with the more serious and scarier rise of political unrest, riots, war and terror on the streets. It felt like it was the end of times, so conversations about the Apocalypse and the Anti-Christ gained prevalence.

This, in turn, led to the birth of the modern subgenre of religious horror movies that equated the fears of changing times and social progress to the devil's work. Religious horror movies of the time like The Exorcist and The Omen could be read as the older generations' reaction to these paradigm shifts and their fear of youth. These movies' antagonists were demon worshipers and cultists who practiced witchcraft and the occult in defiance of the accepted religious status quo. The heroes were part of the clergy who drew their power and strength from God. Faith and religion were the only things that could save the faithful (or at least their souls) from an increasingly sinful world.

The subversion and perversion of religion and societal norms considered to be sacred and true were central themes of the religious horror movies made in the 60s, and especially in Rosemary's Baby. To top it all of, Rosemary's Catholic faith and pure background were used against her. This, however, didn't mean that the movie was a fearful conservative screed against change. Ironically and unlike its contemporaries, it was the older, religious establishment who exploited tradition and faith in Rosemary's Baby. They worked together to oppress -- or in Guy's case, corrupt and radicalize -- the youth embodied by Rosemary.

Rosemary Baby Boasts a Scarily Good Cast

Mia Farrow played well against the villainous performances of John Cassavetes, Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer

Servant Finally Has Its Rosemary's Baby Moment - But It Falls Flat

The finale of Servant has a Rosemary's Baby-like situation to deal with between Dorothy and Leanne, but it's missing key creative ingredients.The term "gaslighting" is thrown around very easily now, applied casually and cynically to trivial matters. But back in 1968, Rosemary's Baby has the best and most unsettlingly realistic depiction of gaslighting and manipulation seen on screen since the term's 1944 film namesake, Gaslight. The chocolate mousse scene alone is enough to spike even the calmest and most tranquil viewer's blood pressure. The same could be said for the scenes at the doctor's office, where the true terror only hits during a rewatch and in hindsight.

A lot has already been said about how Farrow conveyed so much emotion, fear and tragedy in her performance as Rosemary, but her fellow actors deserve equal amounts of praise, or even more. John Cassavetes, in particular, performs a special, mundane and grounded sort of villainy. Guy, played to evil perfection by Cassavetes in one of the greatest roles of his career, is one of the most loathsome characters in cinematic history. It's a testament to his remarkable talent that he portrayed this vile character so believably and convincingly. His form of dismissive and malicious manipulation is a good contrast with the more obtrusive and pushy yet no less vile brand of unscrupulous dishonesty of the Bramford's cult. Cassavetes no doubt took cues from his time on the set of this film for his own illustrious and influential film career from the 70s onwards, especially in his own grounded portrayals of domestic angst.

The supporting cast didn't slouch either, with everyone except for Maurice Evans's tragic and lovable Hutch delivering their most unlikable, manipulative and predatory performances possible. Special mention goes to Roman Castevet and his wife Minnie -- portrayed by Broadway actor Sidney Blackmer and Oscar winner Ruth Gordon, respectively -- because they were literal neighbors from Hell. They were nauseating and ghoulish brown notes personified. Their very presence is uncomfortable. They were so horrible because of how subversive they were of the typically kind, loving and honest grandparents seen in odes to traditional families and conservative values. The Castevets' mere existence in Rosemary's Baby was one of the most effective uses of affable villainy in fiction.

The Ending of Immaculate, Explained

The disturbing finale of Sydney Sweeney's Immaculate is likely to make it one of the most controversial, yet thought-provoking horrors of all time.The cast's stellar performances and the movie's claustrophobic atmosphere would be incomplete without Krzysztof Komeda's spare and eerie soundtrack. Compared to more recent horror films, Rosemary's Baby is calm and quiet. Most of its soundtrack consisted of the ambient din of New York City, the bustle of domestic life, faint renditions of the classic piece "Für Elise" and muffled neighborly chatter. The most overtly scary sound heard was the ominous but otherwise familiar chanting. These earthy and mundane sounds enhanced the horrors of Rosemary's Baby significantly, with just how calm and real they are.

This made the scenes when the music does chime in all the more horrifying. Rosemary's Baby's actual score includes a demented and warped take on Gregorian chanting, discordant and jangling pianos and period-appropriate instrumentations. And then there's the opening theme, "Sleep Safe and Warm" (also known as "Lullaby from Rosemary's Baby"): a creepy little ditty with psychedelic touches. Combined with its slow and deliberate cinematography, especially the uncomfortably slow aerial shots of New York City, Rosemary's Baby's soundtrack is one of the most effective in horror cinema.

Rosemary’s Baby Is Frighteningly Timeless & Relevant

Rosemary's Baby was made in the 60s, but its horrors are still terrifying in the 2020s

REVIEW: The First Omen Scares Beautifully, But Doesn't Deliver Originality

The First Omen is a beautiful film that stands on its own merits, but suffers as a prequel to The Omen and from its derivative plot and horror.The birth of the Anti-Christ and the evil that people do aside, Rosemary's Baby is visually beautiful, even by today's standards and advanced filmmaking technology. Although the Bramford is as creepy as an apartment complex can be, its archaic, Renaissance Revival architecture is stunning. This added to the film's Gothic horror and sense of foreboding. Although most of the film was shot in Los Angeles doubling for New York, the urban setting was filmed with a delicate gaussian blur, a touch of softness that toned down the film's darkness.

The visuals came together to tell the story, and highlighted its complex subtext. This was especially true when the scenery was combined with the beautiful costumes in the form of fabulous Youthquake 60s fashion, sported magnificently by Farrow. When it came to the movie's visual storytelling, the cast's wardrobe was one of its most underrated strengths. Rosemary's plethora of shift dresses, mini skirts, soft colors and childlike details conveyed a feeling of innocence, artlessness and sweetness that complemented her ingenuous personality. Rosemary may be pregnant, but she did not look like a mother in the slightest. She better resembled a child who was helpless and at the mercy of the cruel machinations around her. Her attires also uncomfortably and effectively contrasted the Gothic apartment, and the crude happenings and vile cultists within it.

Rosemary's fashion sense and innocence also served as a counterweight to Guy's dark, drab and mundane clothes, and the coven's crude and aggressively unfashionable looks. The latter were almost always clad in a kaleidoscope of clashing colors. They wore clothes, makeup and accessories that were exaggeratedly bright and out of date. They really looked like monsters who tried and failed to pass off as humans, and wound up looking like mockeries of people instead.