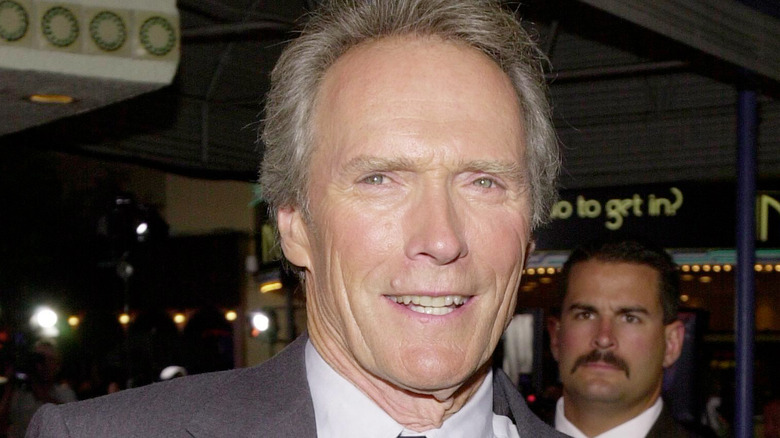

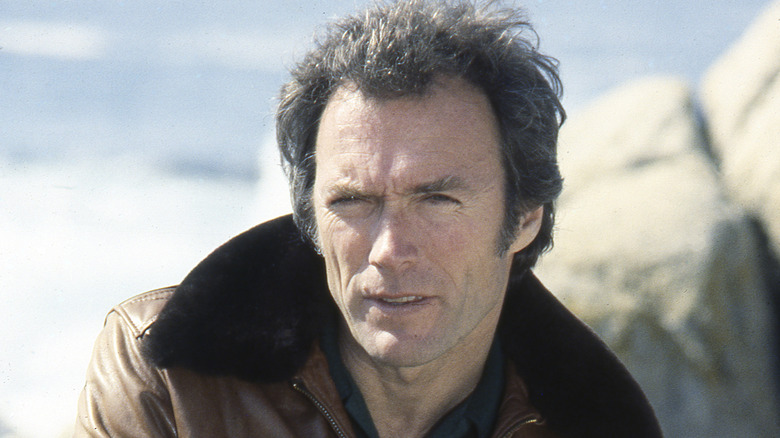

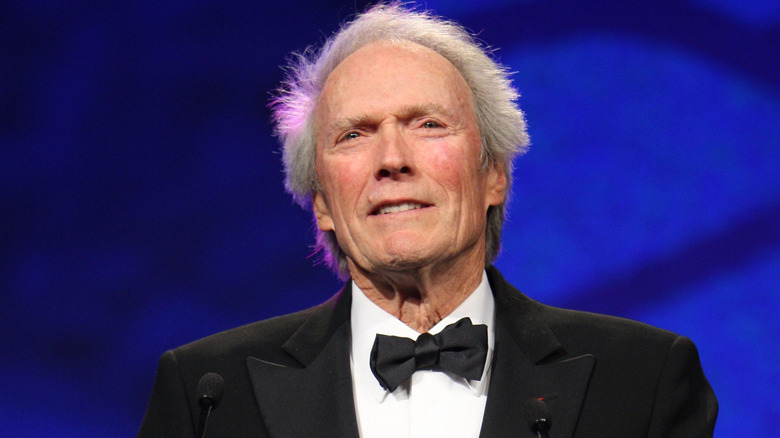

The Dark Reality Of Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood is inarguably a superstar actor and legendary film director, and his name is synonymous with movie tough guys and a macho attitude in general — although his rise to that rare status is fraught with scandal, controversy, hostility, and broken hearts. He's a man who likes things to be done his way. He knows what he wants on a movie set and he takes what he wants in life, and decades of that — he's been a star since the 1960s and continues to work at a high level into his 90s — has left behind a considerable amount of collateral damage. Because his movies are such well-made commercial hits, he's virtually untouchable in the entertainment industry, allowing him to build up a supportive world around himself. Eastwood can do or say what he pleases, and while it might spread a few eyebrow-raising headlines, he still sits atop the Hollywood pack. Here's a look into the dark side of the private and professional life of Clint Eastwood.

His bad behavior toward a director changed the way movies are made

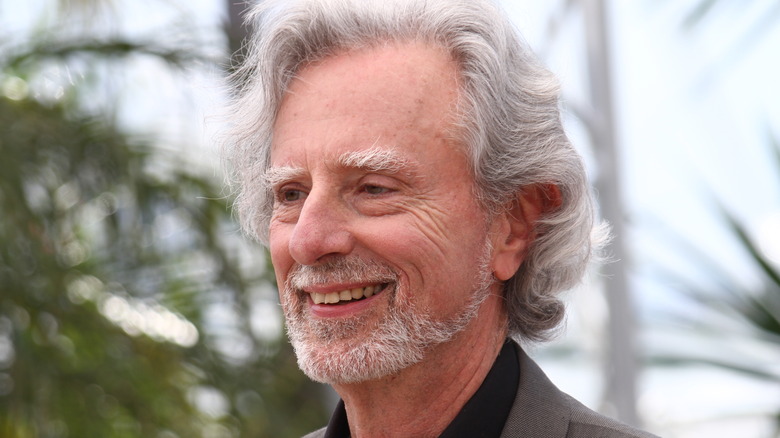

Philip Kaufman (pictured) wrote the script for the 1976 Civil War movie "The Outlaw Josey Wales," then got bumped up to director because the film's star and producer, Clint Eastwood, appreciated Kaufman's creative liberties. In adapting the Forrest Carter source novel, Kaufman opted to have the bad guys relentlessly pursue Eastwood's titular character for the entirety of the film rather than die early on like they do in the book.

Once filming began, Kaufman's slow, thoughtful, and deliberate directing style irritated Eastwood. Kaufman took as much time as he needed to frame shots and get the footage he was after; Eastwood preferred to shoot a scene quickly and without fuss, and move on. One scene took so long to capture that after Kaufman set off in the desert to find a particular location he'd scouted earlier, Eastwood insubordinately led a small group of crew members and shot the scene himself.

A few days later, and under Eastwood's orders, producer Robert Daley fired Kaufman from "The Outlaw Josey Wales." The new director: Eastwood. But this film was a union production, and thus subject to strict labor rules. When news of Eastwood essentially replacing Kaufman with himself got back to the Directors Guild of America, it passed a new provision in its standard contract. Nicknamed "the Clint Eastwood Rule," DGA-affiliated productions cannot allow an actor, or actor-producer, to take the director's job out from under them.

He upset the Marines and one of his closest allies

In the 1970s, Clint Eastwood hired his old friend Fritz Manes to work on his films. Manes toiled on a total of 13 Eastwood movies, variously as a producer, assistant director, stunt performer, and actor. His career in Hollywood, and 40-plus-year friendship with Eastwood, ended when the director made him take the fall for problems with the 1986 movie "Heartbreak Ridge," which explored the U.S. military's intervention in Grenada in 1983. The production required the help of the U.S. Marine Corp, and it was Manes' job to be an envoy between the filmmakers and military officials. Those figures — high-ranking individuals in the Marines and the Department of Defense — publicly criticized "Heartbreak Ridge" upon its release, calling out the film and Eastwood for its numerous factual errors. Because the military wasn't happy, Eastwood blamed Manes and ended his employment.

Still hurt by the events nearly 30 years later, Manes said in Patrick McGilligan's "Clint: The Life and Legend" that working alongside Eastwood was categorically tough, with little reward: "With this guy, if you got any credit for anything it was a miracle." Manes also described in the book the time he allegedly witnessed Eastwood assault his then-wife, Maggie Johnson. "Clint just turned round and knocked Maggie out cold. He really decked her, knocked her clear from the living room into the tub in the bathroom," Manes said (via the Irish Independent). Those recollections led to a $10 million libel lawsuit from Eastwood, who sued McGilligan and his publisher for damaging his reputation.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

He personally and professionally mistreated Sondra Locke

Clint Eastwood began a relationship with Sondra Locke while making "The Outlaw Josey Wales," and they lived together for more than a decade. For the duration of their time together, Locke's acting career consisted entirely of Eastwood projects. "If you were in Clint Eastwood movies, you were in the Clint Eastwood movie business. You weren't in the movie business. You weren't part of Hollywood," Locke told The Washington Post. Locke said she stopped getting offers altogether because filmmakers and casting directors assumed that she only wanted to make movies with Eastwood.

Eastwood broke things off with Locke in 1989, and he let her know their relationship was over by waiting until she'd left the home they shared together, changing the locks, and having her possessions removed. Subsequently, Locke learned that Eastwood had taken up with a woman he'd been secretly seeing, with whom he'd had multiple children. Locke found this particularly traumatic because Eastwood had implored her to terminate pregnancies and submit to a tubal ligation procedure to prevent any more.

After the split, Locke filed a palimony lawsuit, the spousal support equivalent for unmarried people. Eastwood settled the case and negotiated with Warner Bros. a deal for Locke to direct films and develop screenplays. After three years, Warner Bros. hadn't given Locke any projects, so she sued for fraud, suspecting that the powerful Eastwood made the deal to essentially blacklist her from Hollywood. That suit was settled out of court in 1996.

Clint Eastwood may have lied about his tough past

History books got things wrong about the Great Depression, and Clint Eastwood may have, too. Enduring a hardscrabble childhood amidst that 1930s economic fallout is an often-repeated part of Eastwood's story. "There was not much employment. Not much welfare. People barely got by. People were tougher then," Eastwood told Esquire. "We weren't itinerant: it wasn't 'The Grapes of Wrath,' but it wasn't uptown either," the actor told Rolling Stone.

A rough childhood can be a dark and affecting thing, except that Eastwood stretched the truth about his upbringing, according to his former partner, Sondra Locke. When giving testimony in 1996 for a lawsuit filed by Locke, Eastwood again reflected on his financially difficult early years. "My father was typical of the Depression era of people. He always preached a hard work ethic," Eastwood testified, according to Locke's memoir "The Good, the Bad, and the Very Ugly." Locke attested that Eastwood's childhood memories weren't accurate, writing that his family never struggled with money and actually lived in a wealthy neighborhood, owned multiple cars, and held a membership at a California country club.

Eastwood's courtroom testimony also included a mention of his drafting into the U.S. Army in 1951 during the Korean War. He'd frequently discussed his military service in interviews, but according to Locke, he never saw combat, spending his entire spell in the Army working as a lifeguard at the Fort Ord base in California.

He became a small town mayor out of pettiness

When he wasn't down in Los Angeles making movies, Clint Eastwood listed his primary residence in the 1970s and '80s as Carmel-by-the-Sea, a town on the Monterey Peninsula in central coastal California, where he also co-owned the Hog's Breath Inn restaurant. In 1985, the Carmel City Council turned down Eastwood's proposal and plans to build a commercial-use facility next to the Hog's Breath Inn.

Eastwood sued, and the case was settled before a trial could take place. He reached a settlement with the historical preservation-minded city government of Carmel, but Eastwood remained so annoyed and felt so disrespected by the whole affair that he decided to try and take over the city. In January 1986, Eastwood announced plans to run for mayor, promising to scale back on his moviemaking in order to focus his attention on Carmel should he win a two-year term. In the April election, Eastwood garnered 72% of the votes — 2,166 in total in a campaign that cost him $40,000. Eastwood's political career ended with his one mayoral term, although he was considered for George H.W. Bush's vice president slot.

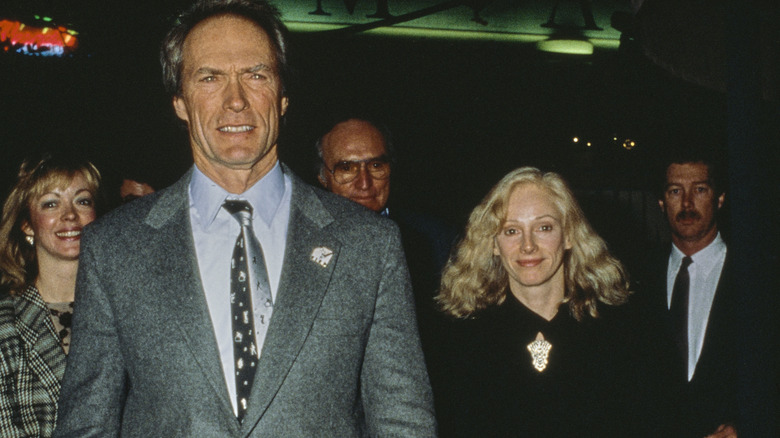

He mistreated Frances Fisher

The first major film role that theatrical actor Frances Fisher scored was a supporting part in the 1989 Clint Eastwood action comedy "Pink Cadillac." Eastwood was in the midst of extracting himself from a relationship with Sondra Locke, and Fisher became his next long-term romantic partner. We know a lot about Eastwood's philandering past, and so did Fisher. But she stayed with the actor for six years, eventually becoming pregnant with their daughter, Franny. Eastwood's behavior during Fisher's labor is what led her to end the relationship.

Fisher unexpectedly went into labor five weeks ahead of schedule while spending time at Eastwood's ranch in Northern California, and she was taken by helicopter to a Redding, California, hospital. "I was in heavy, heaving labor. I'd never done this before. He was standing at the back of the room talking golf to the doctor on duty," Fisher told The People (via The Free Library). "Suddenly a nurse I didn't recognize walked into the room. She strode straight up to Clint and whispered something I couldn't hear. I heard him reply, 'It's not appropriate' and I knew she'd asked for his autograph." Eastwood would sign the autograph anyway. And not long after the delivery and discharge, Fisher broke up with Eastwood, moving out of their home and taking their newborn baby daughter.

He threatened to kill Michael Moore

In January 2005, filmmakers Clint Eastwood and Michael Moore (pictured) were both in attendance at the National Board of Review awards dinner. Eastwood was representing his film "Million Dollar Baby," while Moore was there with "Fahrenheit 9/11," a documentary that relied on ambush-style interviews of prominent public figures about U.S. military actions. Eastwood called out Moore's film during his speech that night. He threatened to "kill" Moore if he were to ever interview Eastwood in such a manner, according to Moore's Facebook. To demonstrate that he wasn't kidding, Eastwood repeated himself, simply and bluntly, to Moore: "I'll kill you." The crowd still laughed, and so Eastwood spoke over them. "I mean it. I'll shoot you." On his Facebook post, Moore provided his take. "I should probably stop here and say that I like Clint Eastwood and I think he was a great filmmaker," he wrote, "but something started to go haywire with Clint in the last decade."

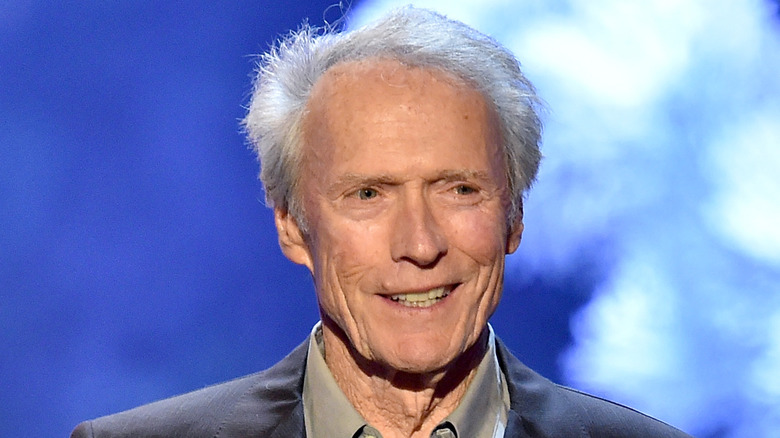

He eviscerated an empty chair

Clint Eastwood has long been known as one of the more conservative big names in the film industry. His politics lean to the right of center, his views corresponding to those of libertarians and Republicans. In 2012, Eastwood spoke at the Republican National Convention. Amidst the events that culminated in the nomination of Mitt Romney as the challenger to President Barack Obama as he sought a second term, Eastwood spoke at length in the form of a one-sided conversation. He delivered specific rebukes to Obama, represented in the exchange by an empty chair. While there were questionable things about Obama's presidency, Eastwood's performance was supposed to demonstrate how the president had no excuses, or nothing to say, to criticism. But to casual viewers, the bit of theater just looked like an elderly gentleman talking to somebody who wasn't there. (Obama easily beat Romney in the general election, too.)

When asked by a reporter in 2016 about the state of American presidential politics, Eastwood admitted that he regretted the format of that speech. "What troubles me is, I guess when I did that silly thing at the Republican convention, talking to the chair," Eastwood told Esquire.

A Clint Eastwood movie so disparaged a dead woman that it led to a slander lawsuit

Kathy Scruggs, a police-beat reporter for one of the U.S.'s major newspapers, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, became moderately famous when she reported on the terrorist bombing of Centennial Olympic Park during Atlanta's 1996 Summer Olympics. Scruggs' stories were among the first filed about the event and investigation, and she broke the news that the top suspect in the crime was a security guard named Richard Jewell. Scruggs cited federal authorities as her source. The truth about the Atlanta 1996 Olympics bombing would eventually emerge and Jewell would be completely exonerated, but he'd forever be linked to the horrific crime, leading him to sue the Atlanta Journal-Constitution for besmirching his good name. In court proceedings, Scruggs declined to identify her exact federal source for the Jewell allegations; she was threatened with imprisonment for her refusal.

Scruggs died in 2001, long before the 2019 release of the Clint Eastwood-directed "Richard Jewell." Olivia Wilde played the prominent role of Scruggs in the movie, which purported to expose how the Atlanta Journal-Constitution ruined Jewell's life, with malicious and negligent intent on the part of Scruggs. To get her information, the film theorizes, Scruggs offered sexual favors to an FBI agent. On behalf of itself and the estate of Scruggs, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution filed a lawsuit against producer Warner Bros., alleging that Eastwood created a false and defamatory portrait of its deceased reporter.

He told Spike Lee to shut up with his allegations of racism

At the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, Spike Lee promoted "Miracle at St. Anna," a World War II drama with a main cast of Black actors. While talking to reporters, he criticized Clint Eastwood's two 2006 World War II films, "Flags of Our Fathers" and "Letters from Iwo Jima," for a lack of Black characters. "Clint Eastwood made two films about Iwo Jima that ran for more than four hours total, and there was not one negro actor on the screen," Lee said (via The Guardian). "I know it was pointed out to him and that he could have changed it. It's not like he didn't know."

Eastwood responded to Lee's criticism in The Guardian, allowing that while a small number of Black soldiers were present at Iwo Jima, none were photographed. "They didn't raise the flag. The story is 'Flags of Our Fathers,' the famous flag-raising picture, and they didn't do that. If I go ahead and put an African-American actor in there, people'd go, 'This guy's lost his mind,'" Eastwood said, adding of Lee, "A guy like him should shut his face."

Celebrity feuds can get out of hand, and this one took a third major filmmaker to resolve it. Lee ran into Steven Spielberg at a basketball game and explained his side, and Spielberg promised to reach out to Eastwood. "And it's hunky-dory. He said he was gonna make a call [to Eastwood], he made it, squashed," Lee told Access.

He doesn't like it when people stand up against injustice

Expecting to win the Best Actor Oscar for "The Godfather" at the 1973 Academy Awards, Marlon Brando sent Sacheen Littlefeather, president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee, to refuse his award as a protest. "And the reasons for this ... are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry," Littlefeather said to both boos and cheers. "I beg at this time that I have not intruded upon this evening and that we will in the future, our hearts and our understandings will meet with love and generosity." A few minutes later, Clint Eastwood headed out on stage to present an Oscar, and he made some withering put-downs about the LIttlefeather speech. "I don't know if I should present this award on behalf of all the cowboys shot in all the John Ford Westerns over the years," he quipped (via The Guardian).

Flash-forward to 2016, and an Eastwood interview with Esquire, in which the celebrity spoke highly of the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump as it served as an antidote to cultural trends that bugged him. "He's onto something, because secretly everybody's getting tired of political correctness, kissing up. That's the kiss-a** generation we're in right now. We're really in a p**** generation," Eastwood said. "We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren't called racist."