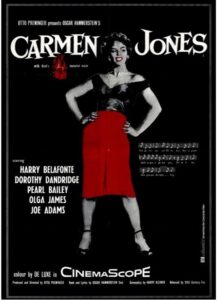

This November, the AFI Catalog shines a spotlight on actress, singer and dancer Dorothy Dandridge, who would have turned 101 this month. Starring in the seminal musical with an all-Black cast, CARMEN JONES (1954), Dandridge became the first African American performer to be nominated for a leading role with a Best Actress Oscar® nomination, and several years later she was honored with a Golden Globe nomination for her titular role in PORGY AND BESS (1959), which marked her final appearance in an American feature film. Shortly after the release of CARMEN JONES, Dandridge became the first Black woman to appear on the cover of Life Magazine, and by the following year she had signed a three-year contract with Twentieth Century-Fox, a studio that intended to launch her as the first African American female screen star. Also in 1955, Dandridge was the first Black performer to take the stage at the exclusive Empire Room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and was the first African American woman to present an Oscar® at the Academy Awards ceremony (for Best Film Editing). Despite the rapid elevation of her career at this time, Dandridge was only cast in one more “major” Hollywood picture (PORGY AND BESS) and died at age 42 in a small apartment, under the stress of considerable financial debt resulting from an abusive second marriage.

This November, the AFI Catalog shines a spotlight on actress, singer and dancer Dorothy Dandridge, who would have turned 101 this month. Starring in the seminal musical with an all-Black cast, CARMEN JONES (1954), Dandridge became the first African American performer to be nominated for a leading role with a Best Actress Oscar® nomination, and several years later she was honored with a Golden Globe nomination for her titular role in PORGY AND BESS (1959), which marked her final appearance in an American feature film. Shortly after the release of CARMEN JONES, Dandridge became the first Black woman to appear on the cover of Life Magazine, and by the following year she had signed a three-year contract with Twentieth Century-Fox, a studio that intended to launch her as the first African American female screen star. Also in 1955, Dandridge was the first Black performer to take the stage at the exclusive Empire Room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and was the first African American woman to present an Oscar® at the Academy Awards ceremony (for Best Film Editing). Despite the rapid elevation of her career at this time, Dandridge was only cast in one more “major” Hollywood picture (PORGY AND BESS) and died at age 42 in a small apartment, under the stress of considerable financial debt resulting from an abusive second marriage.

Protected:

Dorothy Dandridge – AFI CATALOG SPOTLIGHT

Dorothy Dandridge began her career early in life, singing in a duo with her older sister Vivian, billed as the Wonder Children. Their mother, Ruby, left her husband before Dorothy was born and took up a romantic relationship with Geneva “Neva” Williams (also known as Eloise Matthews and “Auntie Ma-ma”), who trained and brutally disciplined the girls while Ruby worked as a cook. Based in Cleveland, the Wonder Children toured the South, making a healthy income at Black schools and churches, but Dandridge was denied a proper education, and was illiterate in her early years. After a hiatus of two years, Dandridge returned to the screen in ISLAND IN THE SUN (1957), a controversial yet widely popular picture depicting a love affair between a Black woman and white assistant to a governor in the West Indies, as well as a flirtation between a white woman and a Black man. Although the film was banned in some Southern cities, provoked a flurry of hate mail to its stars, and instigated unsuccessful campaigns to block its release, ISLAND IN THE SUN was one of the top-grossing movies of 1957. The next year, Dandridge performed her first and only onscreen kiss with a white actor in the French-Italian picture TAMANGO, which incited so much controversy that it was held back from release in America until 1959. After co-starring in THE DECKS THAT RAN RED (1958), Dandridge was cast in her last starring role in an American feature, PORGY AND BESS, a film adaptation of a play that was steeped in dispute over its representation of Black stereotypes, directed by Preminger. The production was plagued by mishaps (including a fire that destroyed the props and costumes) and went way over budget, causing the picture to be a financial failure. According to several first-hand accounts, Preminger was verbally abusive to Dandridge during the entire shoot and the experience was particularly painful for her. Also in 1959, Dandridge married her second husband, Jack Denison, who squandered money from the fading star and left her in bankruptcy when they divorced three years later. Dandridge could no longer support her home and the care of her daughter, so the girl was put into a state mental institution and Dandridge moved to a modest Hollywood apartment. All the while, Dandridge was increasingly trusting alcohol and prescription medication to calm her anxieties, including stage fright, and her behavior was erratic. On September 8, 1965, Dandridge was found naked on the floor of her apartment, unresponsive. The cause of death conflicted between sources, with the Los Angeles Department of Pathology determining that Dandridge was killed from an overdose of anti-depressants and the Coroner’s Office finding that a fracture in her foot triggered an embolism. Watch Dorothy Dandridge perform “Chattanooga Choo Choo” with The Nicholas Brothers in SUN VALLEY SERENADE here: Watch Dorothy Dandridge in CARMEN JONES here: Watch Halle Berry discuss performing the role of Dorothy Dandridge at AFI FEST: Resources: Bogle, Donald. Dorothy Dandridge: A Biography. New York: Amistad, 1999. “Carmen Jones,” American Film Institute Catalog, accessed October 9, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Film/53446-CARMEN-JONES Dandridge, Dorothy and Earl Conrad. Everything and Nothing: The Dorothy Dandridge Tragedy. New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1970. Herringshaw, Deann. Dorothy Dandridge: Singer & Actress. Edina: ABDO Publishing Company, 2011. “Island in the Sun,” American Film Institute Catalog, accessed October 9, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Film/52236-ISLAND-INTHESUN Meares, Hadley Hall. “Tragedy and Triumph: The Dorothy Dandridge Story.” Vanity Fair. October 14, 2020. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2020/10/dorothy-dandridge-biography-life Mills, Earl. Dorothy Dandridge: An Intimate Biography. Los Angeles: Holloway House Publishing Group, 1970. Petersen, Anne Helen. Scandals of Classic Hollywood. New York: Penguin, 2014. “Porgy and Bess,” American Film Institute Catalog, accessed October 10, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Film/53462-PORGY-AND-BESS She learned to quickly memorize information to cover her struggles, and this skill served her well as an actress. At this time, Dandridge became aware of racial segregation and grew to understand her mother’s wish for the girls to become something other than domestic servants. Work dried up for the sisters when the Great Depression hit America, so Ruby moved the family, including Williams, to Hollywood in pursuit of stardom. Ruby, herself, was cast in bit roles, while her daughters continued to polish their act, adding Etta Jones to the group and renaming it the Dandridge Sisters in 1934. The three girls found success, including performances at the Cotton Club and the Apollo Theater in New York City, and by the following year, at age 13, Dandridge was hired for her first uncredited appearance on the big screen in an Our Gang short, titled TEACHER’S BEAU. The Dandridge Sisters were also cast in a number of films in the late-1930s, including the Marx Brothers’ A DAY AT THE RACES (1937), leading up to Dandridge’s first credited solo role in FOUR SHALL DIE (1940). The following year, in 1941, Dandridge was featured in the popular musical SUN VALLEY SERENADE, which reconnected her onstage with the man who would become her first husband, Harold Nicholas, of the Nicholas Brothers—the two had previously met at the Cotton Club and were married in 1942.

She learned to quickly memorize information to cover her struggles, and this skill served her well as an actress. At this time, Dandridge became aware of racial segregation and grew to understand her mother’s wish for the girls to become something other than domestic servants. Work dried up for the sisters when the Great Depression hit America, so Ruby moved the family, including Williams, to Hollywood in pursuit of stardom. Ruby, herself, was cast in bit roles, while her daughters continued to polish their act, adding Etta Jones to the group and renaming it the Dandridge Sisters in 1934. The three girls found success, including performances at the Cotton Club and the Apollo Theater in New York City, and by the following year, at age 13, Dandridge was hired for her first uncredited appearance on the big screen in an Our Gang short, titled TEACHER’S BEAU. The Dandridge Sisters were also cast in a number of films in the late-1930s, including the Marx Brothers’ A DAY AT THE RACES (1937), leading up to Dandridge’s first credited solo role in FOUR SHALL DIE (1940). The following year, in 1941, Dandridge was featured in the popular musical SUN VALLEY SERENADE, which reconnected her onstage with the man who would become her first husband, Harold Nicholas, of the Nicholas Brothers—the two had previously met at the Cotton Club and were married in 1942. While caring for a daughter born with severe brain damage and navigating an abusive relationship over the next decade, Dandridge continued to work as a performer in nightclubs and in jukebox “soundies”(an early precursor to music videos), as well as in film, earning her first starring role in BRIGHT ROAD (1953) with Harry Belafonte. Soon after, she enthusiastically petitioned for the title role of CARMEN JONES, whose director, Otto Preminger, initially believed she was wrong for the part. Dandridge not only won the role that would bring her an Oscar® nomination and transform her career, but she captured Preminger’s heart, and the pair would continue an affair (Dandridge was divorced, but Preminger was still married) over the next four years. A pregnancy resulted from the relationship; however, Dandridge was forced into an abortion by Fox studio executives who had a vested interest in keeping her a sex symbol, as noted by author Anne Helen Petersen. Anti-miscegenation laws existed throughout the nation during this time, even though they were repealed in California in 1948, making the studios worry about the public’s opinion of an interracial romance. Preminger also exerted control over Dandridge’s career, influencing her to only accept leading roles, which caused her to lose exposure in important movies, including THE KING AND I (1956). Some sources note that Dandridge declined the part after she was cast because she did not want to perform the role of an enslaved person. Either way, her last-minute departure from the production resulted in earning a negative reputation in Hollywood and made it more difficult for her to find work.

While caring for a daughter born with severe brain damage and navigating an abusive relationship over the next decade, Dandridge continued to work as a performer in nightclubs and in jukebox “soundies”(an early precursor to music videos), as well as in film, earning her first starring role in BRIGHT ROAD (1953) with Harry Belafonte. Soon after, she enthusiastically petitioned for the title role of CARMEN JONES, whose director, Otto Preminger, initially believed she was wrong for the part. Dandridge not only won the role that would bring her an Oscar® nomination and transform her career, but she captured Preminger’s heart, and the pair would continue an affair (Dandridge was divorced, but Preminger was still married) over the next four years. A pregnancy resulted from the relationship; however, Dandridge was forced into an abortion by Fox studio executives who had a vested interest in keeping her a sex symbol, as noted by author Anne Helen Petersen. Anti-miscegenation laws existed throughout the nation during this time, even though they were repealed in California in 1948, making the studios worry about the public’s opinion of an interracial romance. Preminger also exerted control over Dandridge’s career, influencing her to only accept leading roles, which caused her to lose exposure in important movies, including THE KING AND I (1956). Some sources note that Dandridge declined the part after she was cast because she did not want to perform the role of an enslaved person. Either way, her last-minute departure from the production resulted in earning a negative reputation in Hollywood and made it more difficult for her to find work. Throughout her life, Dandridge was challenged with a steep upward climb to success in the face of racism and sexism in the film industry and beyond. She was passed up for parts for Black women that were ultimately performed by white actresses in blackface, and she was not considered a viable leading lady paired with a white actor due to the nation’s widespread endorsement of anti-miscegenation. For many years, Dandridge’s lack of opportunities in Hollywood led her to pursue work at hotel nightclubs to finance her daughter’s costly care. At these venues, particularly in Las Vegas, which was segregated at the time, Dandridge was often forced to find accommodations on the outskirts of town, or else required to remain shut in her room when not on stage. Dandridge endured crippling anxiety, stemming from her childhood traumas, which left her at times in a state of near paralysis, and she was deeply concerned about justly representing the African American community, afraid of accepting roles that upheld virulent stereotypes. Dandridge was a longtime member of the NAACP and attended meetings of the Urban League, organizing to empower communities of color. Her historic Oscar® nomination came soon after the Supreme Court ruled against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, and gave Black Americans hope for a better future in which they would be acknowledged as equals. Dandridge inspired many young actresses of color to pursue their dreams, including Halle Berry, who championed, produced and starred in the HBO film INTRODUCING DOROTHY DANDRIDGE (1999). Several years later, when Berry followed in Dandridge’s footsteps to become the first African American woman to win the Best Actress Oscar®, she began her acceptance speech by acknowledging Black actresses, starting with Dandridge—a trailblazer and a powerful precedent to greater representation in America’s cinematic depiction of its beautifully diverse culture.

Throughout her life, Dandridge was challenged with a steep upward climb to success in the face of racism and sexism in the film industry and beyond. She was passed up for parts for Black women that were ultimately performed by white actresses in blackface, and she was not considered a viable leading lady paired with a white actor due to the nation’s widespread endorsement of anti-miscegenation. For many years, Dandridge’s lack of opportunities in Hollywood led her to pursue work at hotel nightclubs to finance her daughter’s costly care. At these venues, particularly in Las Vegas, which was segregated at the time, Dandridge was often forced to find accommodations on the outskirts of town, or else required to remain shut in her room when not on stage. Dandridge endured crippling anxiety, stemming from her childhood traumas, which left her at times in a state of near paralysis, and she was deeply concerned about justly representing the African American community, afraid of accepting roles that upheld virulent stereotypes. Dandridge was a longtime member of the NAACP and attended meetings of the Urban League, organizing to empower communities of color. Her historic Oscar® nomination came soon after the Supreme Court ruled against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, and gave Black Americans hope for a better future in which they would be acknowledged as equals. Dandridge inspired many young actresses of color to pursue their dreams, including Halle Berry, who championed, produced and starred in the HBO film INTRODUCING DOROTHY DANDRIDGE (1999). Several years later, when Berry followed in Dandridge’s footsteps to become the first African American woman to win the Best Actress Oscar®, she began her acceptance speech by acknowledging Black actresses, starting with Dandridge—a trailblazer and a powerful precedent to greater representation in America’s cinematic depiction of its beautifully diverse culture.

Real Jones

A rare beauty…forever.

Proper respect AFI..SALUTE

Daniel Powell

The Goat Of Singing & Acting & There Will Never Be Another Like Her Not Even Closes !..!.!!.