Chapters

Battle of Lake Trasimene was Hannibal’s second victory over the Romans in the Second Punic War. The ambush led to the massive slaughter of the Romans. Apparently, a nearby stream supplying water to the lake, due to the mixing of a large amount of blood, was called Sanguineto, or “Blood River”.

Background of events

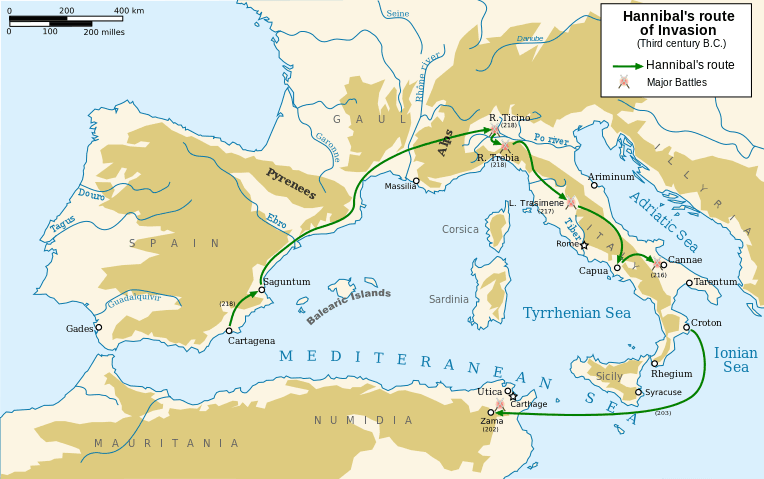

The defeat of the Romans at the Battle of the River Ticinius (November 218 BCE) was the first defeat of the Romans in the Second Punic War in Italy. The concerned Senate decided to summon consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who had previously been sent to Africa along with 160 ships (quinquereme) to obtain a replenishment of troops and supplies. During this trip, Sempronius captured Malta by defeating Carthaginians. Longus, returning to his homeland, against the advice of Cornelius Scipio (father of Scipio Africanus) attacked Hannibal’s army over the Trebia River in December this year and suffered a devastating defeat. In January 217 BCE, defeated Sempronius with 10,000 soldiers returned to Rome.

The victory of Hannibal in the battle over Trebia concerned the Romans. New plans for counteracting the threat from the north began to be prepared. The Roman Senate decided to appoint new consuls for 217 BCE. They were Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius. Consul Servilius Geminus took command of the army of Cornelius Scipio, while Flaminius was to take over the remainder of the Roman army from the river Ticinius. As the Roman legions were clearly depleted as a result of the defeat over Trebia, it was decided to announce the recruitment for four more legions. These new units, along with the remains commanded by Flaminius, were divided between two consuls. After the battle of Trebia, Flaminius’s army headed south to prepare for the defence of Rome. Hannibal followed the consul’s forces, which at some point he even managed to outrun. Flaminius was forced to speed up his march and fight the battle with Hannibal before he reached the capital of the Roman state. In turn, Consul Servilius and his legions were to join the army of Flaminius and support him in the battle.

Hannibal tried to lure Flaminius’s army into a place he liked. Hannibal deliberately devastated the land, forcing Flaminius to protect the area and causing his legions to move after the Carthaginians. At the same time, Hannibal tried to discourage Rome’s allies from supporting the Eternal City, arguing that the Romans were unable to protect cities on the Apennine Peninsula. Eventually, Flaminius decided to set up camp in Arretium. Despite the devastating actions of the Carthaginian army in the Italian land, the consul remained passive and attentive. Hannibal decided to encircle the Roman army from the left flank, thus cutting it off from Rome. However, the consular army still remained in the Arretium camp. Hannibal decided to force his rival to confront. The Carthaginian commander began his march towards Puglia, hoping that Flaminius would follow him and that there would be a battle in the area chosen by Hannibal. Flaminius, desiring revenge for the destruction of the village and wanting to cope with growing criticism in Rome, finally set off against Hannibal. As Sempronius points out, Flaminius was impetuous, too self-confident and lacked self-control. Consul Flaminius was not a brilliant leader. He knew much more about politics. His advisers suggested that he send troops and press Hannibal to stop looting in the provinces. During this time the meals of the second consul, Servilius, were to come.

When Hannibal passed Lake Trasimeno, he found himself in an area that made it possible to prepare an ambush. Having learned about the departure of Roman troops from the camp, Hannibal decided to start preparations for the upcoming battle. In the north, there were a lot of wooded hills along the shore of the lake. His cavalry and Gallic infantry hid in the forests of the mountains. Light infantry troops did the same. Hannibal set up a camp on a hill near the shore, having very good visibility to the areas between the mountains where Carthaginian troops were hidden and the lake. Heavy infantry troops of Iber, Celts and Africans stood in front of the camp. The night before the battle, Hannibal ordered his men to light fires in the Tuoro hills, at a considerable distance, to convince the Romans that his forces were farther than they really were. Troops remaining in hiding were to wait for the signal to attack.

Armies

Roman army

Roman forces had about 30,000 well-armed soldiers. Flaminius abandoned sending scouts, thinking that the Carthaginian army was still far away. So he ordered a march along the shores of the lake.

Carthaginian army

Carthaginian forces were around 40,000 people. This army was a jumble of different nations. The composition of the army wore a trail of wandering from Africa. Among these soldiers were the Numids, Libyans, Iberians, and Ligurians. There was one elephant in the army – Surus, who was the only survivor of the march through the Alps.

Battle

On the morning of June 21, under cover of fog, Hannibal sent his light cavalry to block Romans’ anticipated escape route; the rest of the forces waited hidden along the road the Romans would come. Hannibal was to give orders to simultaneously attack all his armies.

At that time, Roman soldiers marched east along the road along Lake Trasimensky, not expecting an ambush. To their disadvantage, the lake areas were covered with dense fog. At one point, it turned out that the Romans were trapped, and at the signal of trumpets, Carthaginian troops deployed on the hills attacked the stretched Roman columns that were on the march. This attack, carried out suddenly, by surprise and closing all escape routes, brought the expected result. The front and rear columns were surrounded, thus preventing the Romans from escaping. The Roman army was unable to form ranks, which resulted in the slaughter of soldiers. It was a modification of Hannibal’s later manoeuvre with Cannae, this time mainly using the terrain and the element of surprise.

The short, four-hour battle ended with a total defeat of the Romans pushed to the shores of the lake, who in panic threw themselves into the water in escape from the Carthaginian army and drowned or were killed by Hannibal’s warriors. 15,000 Roman soldiers were killed, including Flaminius responsible for the defeat. This is how Titus Livius describes the moment of his death:

For almost three hours the fighting went on; everywhere a desperate struggle was kept up, but it raged with greater fierceness round the consul. He was followed by the pick of his army, and wherever he saw his men hard pressed and in difficulties he at once went to their help. Distinguished by his armour he was the object of the enemy’s fiercest attacks, which his comrades did their utmost to repel, until an Insubrian horseman who knew the consul by sight—his name was Ducarius—cried out to his countrymen, “Here is the man who slew our legions and laid waste our city and our lands! I will offer him in sacrifice to the shades of my foully murdered countrymen.” Digging spurs into his horse he charged into the dense masses of the enemy, and slew an armour-bearer who threw himself in the way as he galloped up lance in rest, and then plunged his lance into the consul.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, 22.6

10,000 Roman soldiers escaped and reached Rome. The remaining approximately 6,000 Romans were captured by Maharbal, chieftain Hannibal, who promised them freedom if they handed over their weapons. The Carthaginians did not keep their word and all were sold into slavery.

Hannibal’s side was 1,500 (according to Polybius) / 2,500 (according to Livy) victims, the majority of whom were Gauls.

Interestingly, Titus Livius reports that during the battle there was to be a strong earthquake in the area, which, however, neither side felt due to the involvement in the fight1.

Consequences

Hannibal, with his victory over Lake Trasimeno, proved that he was a brilliant commander and a serious threat to Rome’s independence. The battle led to the massive slaughter of the Romans, and the ambush itself is considered one of the largest in history.

News of the defeat at Lake Trasimeno caused panic in the capital. The Senate decided to appoint dictator Fabius Maximus; such action was extremely rare and only in the event of a definite threat to the Republic. The dictator was an extraordinary official (extraordinarius), who was given absolute power for a maximum period of six months to prevent extraordinary crises, for example during a heavy war or internal revolt.

Fabius Maximus decided to avoid an open clash with the Hannibal army, waging a war of exhaustion with the Carthaginians. The Appian of Alexandria described it well:

Fabius followed Hannibal closely, but did not come to an engagement with him, although often challenged. He kept careful watch on his enemy’s movements, and lay near him and prevented him from besieging any town. After the country was exhausted Hannibal began to be short of provisions. So he traversed it again, drawing his army up each day and offering battle. Fabius would not come to an engagement, although his master of horse, Minucius Rufus, disapproved of his policy, and wrote to his friends in Rome that Fabius held back on account of cowardice.

– Appian from Alexandria, Roman history, VII.12

This tactic proved to be costly for Rome, as it led to the destruction of large areas of the country. It was also painful for the pride of the Romans, forced to give way to Carthaginian forces. However, thanks to this strategy Fabius managed to prevent the siege of any of the cities; notoriously harassed Hannibal, and then pushed his forces into the mountainous regions of the Apennine Peninsula, where the Carthaginians could not develop their ride. He also managed to break Carthaginian supply lines. The tactic adopted by Maksimus got its name – “Fabian strategy”.

Despite these successes, impatience grew in Rome and voices appeared demanding more decisive action in the fight against the enemy. Fabius’s passivity in the face of the damage done by Carthaginians only aggravated his dislike of the dictator. After the expiry of his dictatorship, his command of the army was taken away. The new consuls have decided to launch offensive activities and attack Hannibal’s forces, however, in the Battle of Cannae (216 years BCE) they suffered a defeat in the clash with his forces. Rome found itself on the brink of destruction.