Dorothy Arnold: Disappearance of a New York Socialite

Who Was Dorothy Arnold?

Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold was an heiress and American socialite who disappeared in New York City on December 12, 1910. A radiant young woman, Dorothy lived a privileged life in New York's Upper East Side.

When she first vanished, her father didn’t want to alert the police and instead hired private investigators. Despite his efforts to find his daughter, the circumstances surrounding her disappearance remains a mystery.

It’s a case that has intrigued and mystified residents of New York for decades.

Early Years

Dorothy was born July 1, 1885, in New York City, the second of four children of Francis Rose Arnold and his wife, Mary Martha Parks Arnold. She had an older brother, John, born in 1884, and two younger siblings, Dan, born in 1888 and a sister, Marjorie, born in 1891.

Dorothy’s father was a Harvard graduate and senior partner of F.R. Arnold & Co., an importer of fine goods. Francis had a sister Harriette Maria Arnold who was the wife of Rufus W. Peckham, a renowned Supreme Court Justice.

Dorothy’s paternal family were English descendants of passengers who arrived in America on the Mayflower, while Dorothy’s maternal family was from Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The family's social prominence meant that they were included in the Social Register, a list of well-connected families now owned by Forbes.

Dorothy attended the Veltin School for Girls in New York City. She majored in literature and language, graduating in 1905 from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania.

After graduating, Dorothy lived at her family’s home at 108 E. 79th Street, where she placed her aspirations in writing. She hoped to become a published writer and move to Greenwich Village, where creative people lived.

Her parents discouraged her dreams. Her family teased her when she told them of her aspirations, which undoubtedly tormented her.

In the spring of 1910, Dorothy submitted a story to McClure’s magazine, but it was rejected. She then submitted a second story, “The Poinsettia and the Flame,” which was also rejected. Dorothy’s close friends said the rejection left her depressed and ashamed. Her father prevented her from leaving the house and told her: “A good writer can write anywhere.” Despite the setbacks and rules, Dorothy continued to pursue a writing career, but with no success.

Dorothy's Disappearance

On the morning of December 12, 1910, Dorothy told her mother she was shopping for a dress for her younger sister’s debutante party. Mary offered to go along, but Dorothy told her she would go alone.

The Park and Tilford candy store where Dorothy Arnold bought chocolates the morning she vanished.

Library of Congress

Dorothy left home at approximately 11 a.m. and walked to the Park & Tilford store, where she bought a half-pound of chocolates on her family's account. She had about $30.00 cash (close to $940 today).

That day she was dressed to the nines. She wore a navy-blue serge suit with a white Victorian Style neck, tan gloves, and a black fox fur muff for warmth. She would also stash her money there. Her hair was drawn up in a pompadour, and she wore a black velvet hat. She accessorized with a “lover’s knot” ring, a carved barrette, an imitation tortoiseshell comb, and lapis lazuli earrings.

Brentano’s Book Store on 27th Street and Fifth Avenue, where Dorothy was last seen.

Museum of the City of New York

It is known that Dorothy left the candy store at about noon and proceeded to walk 22 blocks south to Brentano’s bookstore, where she bought Engaged Girl Sketches, a book of humorous essays by Emily Calvin Blake. Clerks at both stores stated Dorothy was courteous and was not acting strange.

(The Knickerbocker Trust Company at Fifth Avenue and 27th Street at the intersection where Dorothy Arnold was last seen.

Outside of the bookstore, Dorothy ran into her friend Gladys King. Gladys recalled briefly speaking and that Dorothy was in a good mood. Dorothy told Gladys that she was going to walk home through Central Park.

Dorothy walked away and waved twice, looking back each time. That was the last time Gladys ever saw her friend.

Whether Dorothy told a fib that day and never went to find a dress is unknown.

It was early evening, and Dorothy had yet to return home. After midnight, Elsie Henry, one of Dorothy’s friends, called her house to see if she had returned home. Her mother Mary answered the telephone and told Elsie that Dorothy had returned home and gone to bed with a headache.

The Investigation

Attempting to keep their daughter’s disappearance out of the news, Francis contacted John S. Keith, a friend and attorney, on December 13, 1910. Keith immediately went to the Arnolds' home and searched Dorothy’s room. He found nothing missing but the clothes she had been wearing.

Keith also found personal letters and foreign postmarks on her desk, two folders for transatlantic ocean liners, and burned papers in the fireplace. The family believed the burned papers were the rejected manuscripts. Keith visited New York City hospitals, morgues, and jails, looking for Dorothy.

Pinkerton investigators were hired and joined the search, visiting everywhere Dorothy may have frequented, but they would need more information to lead them closer to solving the case. The investigators questioned Dorothy’s former classmates and friends.

Pinkerton investigators speculated that Dorothy may have eloped with a European man. They searched marriage records but found nothing. Francis paid Pinkerton to send investigators overseas to search ocean liners.

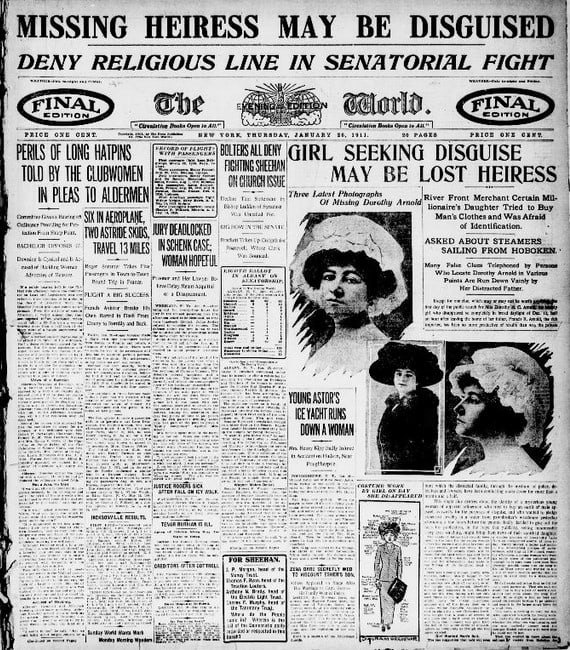

Press Conference

Keith and Pinkerton convinced Francis and Mary to report their daughter missing to the New York City Police Department (NYPD). With no evidence of a crime, the police persuaded Francis to hold a press conference to gain publicity. Francis refused at first.

With additional persuasion, Dorothy’s father finally agreed. On January 25, 1911, Francis held a press conference at his office and offered a $1,000 reward (about $31,000 today) for her return.

Of course, the press responded en masse. Reporters asked Francis if he thought his daughter was still alive and if she had possibly run away with a man, as she was not permitted to date.

“I would have been glad to see her associate more with young men than she did, especially some young men of brains and position whose profession or business would keep him occupied. I don’t approve of young men who have nothing to do,” Francis told the reporters.

George “Junior” Griscom was a young man with whom Dorothy Arnold had a relationship before her disappearance.

Rebecca Makka

Recommended

Secret Lover

The reporters quickly discovered that Francis had been referencing George “Junior” Griscom, a 42-year-old engineer from a wealthy Pennsylvania family. Dorothy had met George while attending Bryn Mawr and was in a romantic relationship with him.

George didn’t have much going for him in personality or looks, but the young lady with a rebellious spirit found something attractive about the much older man.

Reporters gathered information that Dorothy lied to her parents and told them she would visit a former classmate in Boston in September 1910. Dorothy had instead spent a week in a hotel with George. Dorothy’s parents discovered the meeting after Dorothy pawned $500 worth of jewelry to finance their stay at the hotel.

When Dorothy returned home, her parents were adamant she not see the man again, but Dorothy continued corresponding with George long after. They last met in November before George left on vacation with his parents.

After Dorothy vanished, George was found in Florence, Italy vacationing with his parents. Francis sent a telegram to George asking for any information about Dorothy, to which George responded that he knew nothing.

Mary and her brother John even traveled to Italy to grill George in person, but he maintained he needed additional information. When George returned to the United States in February 1911, he told reporters that he intended to marry Dorothy when she returned—that is if her mother allowed it, but Mary said she would never approve of marriage to him.

Possible Sighting

In February 1911, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that George’s hotel room staff saw a veiled woman they thought looked like Dorothy. They said they observed George and the woman have a serious talk, and the woman seemed troubled. Following that report, George spent thousands of dollars placing ads in national newspapers asking her to come home.

Search Efforts

At the end of January 1911, NYPD made it clear they thought Dorothy had run away and would return on her own. However, the Arnold family believed Dorothy was dead. Dorothy's father Francis told the reporters that he believed Dorothy had been attacked and murdered walking home through Central Park and her body was in the Central Park Reservoir.

Francis stated that he had two clues, but would keep the information and where he got it private. Dismissing this theory, the police told him that his daughter could not be in the reservoir because in the days preceding Dorothy’s disappearance, the temperature was only 21 degrees, and the reservoir was frozen.