Buddhism in Vietnam

Buddhism in Vietnam - Buddhism may have first come to Vietnam as early as the 3rd or 2nd century BCE from South Asia or from China in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[1]

The territory of modern-day Vietnam was divided amoung three different states for most of pre-modern history. In the north, the state of Nam Viet (the predecessor to the modern Vietnamese state) was largely a vassal state of the Chinese Empire from 111 BC until 939 CE, and as such Chinese language and culture, including Chinese forms of Buddhism, were integrated into the Vietnamese culture. The Chinese Chan school (Thien in Vietnamese) and the Pure Land school became the most influential schools in the Nam Viet region. The Thien school was most influential in monasteries and among the elites, while the Pure Land school was most influential among ordinary people. By the tenth century, Buddhism flourished among all classes of people.[2]

In the central region of modern-day Vietnam, was the kingdom of Champa, which from the third century onwards was influenced by Indian forms of Sravakayana and Mahayana Buddhism, as well as forms of Hinduism. In the south, the Mekong Delta region was part of the Khmer Empire from the 10th century to the 17th century. The Khmers adopted Theravada Buddhism from the 13th century onwards.

From the fifteenth century onwards, the northern Viet state expanded southward, conquering the Champa kingdom and enventually annexing the Mekong Delta from the Khmer state. The Viet ethnic group eventually settled throughout the central and southern regions of modern-day Vietnam, likely often displacing the Cham and Khmer ethnic groups. Forms of East Asian Buddhism were brought to the rest of Vietnam with this southward expansion, though other forms Buddhism are also practiced, particularly in the south near Cambodia.[2]

History

Three regions of pre-modern Vietnam

In the early period of the Common Era, the area of modern-day Vietnam was divided among three different states:

- The northern region of Nam Viet was largely a vassal state the Chinese Empire from roughly 111 BCE until 1000 CE, and absorbed many aspects of Chinese culture, including the Chinese forms of Mahayana Buddhism.

- The central region, was part of the Champa kingdom from the late 2nd century until the 15th century.

- The southern Mekong Delta region was part of various Cambodian kingdoms until the 17th century.

The northern Nam Viet state

The region of Nam Viet (later known as Dai-Viet), centered in the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam, was the predecessor to the modern Vietnamese state. Nam Viet was largely a vassal state of the Chinese Empire from 111 BC until 939 CE, and as such Chinese language and culture, including Chinese forms of Buddhism, were integrated into the Vietnamese culture. The city Luy Lâu, a regional capital within Nam Viet, became an important regional center of Mahayana Buddhism.[note 1]

The Chinese Chan school (Thien in Vietnamese) and the Pure Land school became the most influential schools in the Nam Viet region. The Thien school was most influential in monasteries and among the elites, while the Pure Land school was most influential among ordinary people. By the tenth century, Buddhism flourished among all classes of people.[2]

As the Viet state expanded southward from the 15th century onwards, the Chinese forms of Buddhism were brought to the central and southern regions of modern-day Vietnam.

The central Champa state

In the central region, the kingdom of Champa emerged around present-day Danang in the late 2nd century AD. The Champa kingdom was heavily influenced by Indian culture; they adopted the Hindu religion and the Sanskrit language. By the 8th century Champa had expanded southward to include what is now Nha Trang and Phan Rang.

After the Cham–Vietnamese War (1471), the Champa state was greatly diminished. The kingdom was reduced to a small enclave near Nha Trang with many Chams fleeing to Cambodia.[4][5]

The kingdom was formally annexed into Vietnam in 1832.[6]

The southern Mekong Delta region

The southern region of modern-day Vietnam, around the Mekong Delta, was part of successive Cambodian states until the 18th century, when the region was annexed and settled by the Vietnamese. "Cambodians, mindful that they controlled the area until the 18th century, still call the delta Kampuchea Krom, or ‘Lower Cambodia’."[7]

From the 1st to 6th centuries AD, the Mekong Delta was part of the kingdom of Funan. "Funan, known as Nokor Phnom to the Khmers, was centred on the walled city of Angkor Borei, near modern-day Takeo. The principal port city of Funan was Oc-Eo in the Mekong Delta and archaeological excavations here tell us of contact between Funan and China, Indonesia, Persia and even the Mediterranean."[8]

Funan was heavily influenced by Indian culture. The Sanskrit language was adopted at court, and it appears that the main religion was Hinduism until around the 5th century, when Buddhist doctrines gained influence.

There is a record in China of two Buddhist monks from Funan, named Mandrasena and Sanghapala,[9]:58,92 who visited China in the 5th and 6th centuries and translated some texts from Sanskrit (or Prakrit) into Chinese.[10] Among these texts they translated is the Mahayana Saptaśatikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, also called the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Mañjuśrīparivarta Sūtra.[11]

After the decline of the kingdom of Funan, the region was absorbed into the Khmer Empire from around 900 C.E. The official religions of the Khmer included both Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism until the 13th century, when Theravada Buddhism was introduced from Sri Lanka. Therevada Buddhism became the official religion.[12]

The Mekong Delta region was annexed and settled by the Vietnamese Nguyen lords in the 17th century.

Dynastic period of Nam Viet (Northern Vietnam)

Early period

There are conflicting theories regarding whether Buddhism first reached Vietnam during the 3rd or 2nd century BCE via delegations from India, or during the 1st or 2nd century from China.[13]

In Nam Viet (northern Vietnam), by the end of the second century CE, the city of Luy Lâu, northeast of the present day capital city of Hanoi, had developed into a major regional Mahayana Buddhist center. Luy Lâu was visited by Indian Buddhist missionary monks en route to China.[3] The monks followed the maritime trade route from the Indian sub-continent to China used by Indian traders. A number of Mahayana sutras and the agamas were translated into Classical Chinese there, including the Sutra of Forty-two Chapters and the Anapanasati Sutta.

Nam Viet was the birthplace of Buddhist missionary Kang Senghui who was of Sogdian origin.[14][15]

Over the next eighteen centuries, Vietnam and China shared many common features of cultural, philosophical and religious heritage. This was due to geographical proximity to one another and Vietnam being annexed twice by China. Vietnamese Buddhism is thus related to Chinese Buddhism in general, and to some extent reflects the formation of Chinese Buddhism after the Song dynasty.[16] Theravada Buddhism, on the other hand, would become incorporated through the southern annexation of Khmer people and territories.

Independent era

The Viet state achieved independence from China in 969 CE, and with the exception of a Chinese takeover from 1407–1427 CE, remained independent until the French colonial era.

During the Đinh dynasty (968-980), Buddhism was recognized by the state as an official faith (~971) by the Vietnamese monarchs.[17] The Early Lê dynasty (980-1009) also afforded the same recognition to the Buddhist church. The growth of Buddhism during this time is attributed to the recruitment of erudite monks to the court as the newly independent state needed an ideological basis on which to build a country. Subsequently, this role was ceded to Confucianism.[18]

Vietnamese Buddhism reached its zenith during the Lý dynasty (1009–1225) beginning with the founder Lý Thái Tổ, who was raised in a pagoda.[19] All of the kings during the Lý dynasty professed and sanctioned Buddhism as the state religion. This endured with the Trần dynasty (1225–1400) but Buddhism had to share the stage with the emerging growth of Confucianism.

By the 15th century, Buddhism fell out of favor with the court during the Later Lê dynasty, although still popular with the masses. Officials like Lê Quát attacked it as heretical and wasteful.[20] It was not until the 19th century that Buddhism regained some stature under the Nguyễn dynasty who accorded royal support.[21]

French colonial period

The French colonial period lasted from approximately 1858-1945. This period saw an increase in the influence of Catholic converts, who were often seen as collaborators with the French.

A Buddhist revival movement (Chấn hưng Phật giáo) emerged in the 1920s in an effort to reform and strengthen institutional Buddhism, which had lost grounds to the spread of Christianity and the growth of other faiths under French rule. The movement continued into the 1950s.[22]

Republican period of Vietnam

In September 1945, Hồ Chí Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. This was followed by war with the French and the formal division of the country in 1954 into North and South Vietnam. In South Vietnam, President Ngô Đình Diệm, a member of the Vietnamese Catholic minority, was accused of pursuing anti-Buddhist policies, leading to civil strife.[23][24][25][26][27]

With the fall of Saigon in 1975, the whole nation came under Communist rule; many religious practices including Buddhism were discouraged. Organized sangha were suppressed. In the North the government had created the United Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, co-opting the clergy to function under government auspices. However, in the South, the Unified Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam still held sway and openly challenged the communist government. The Sangha leadership was thus arrested and imprisoned; Sangha properties were seized and the Sangha itself was outlawed. In its place was the newly created Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, designed as the final union of all Buddhist organizations, now under full state control.

Since Đổi Mới (1986) many reforms have allowed Buddhism to be practiced relatively unhindered by individuals. However no organized sangha is allowed to function independent of the State. It was not until 2007 that Pure Land Buddhism, the most widespread type of Buddhism practiced in Vietnam, was officially recognized as a religion by the government.[28]

Overseas

After the fall of South Vietnam to communism in 1975 at the end of the Vietnam War, the first major Vietnamese Buddhist community appeared in North America. Since this time, the North American Vietnamese Buddhist community has grown to some 160 temples and centers.

The most famous practitioner of synchronized Vietnamese Thiền in the West is Thích Nhất Hạnh who has authored dozens of books and founded the Dharma center Plum Village in France.

Thích Nhất Hạnh's Buddhist teachings have started to return to a Vietnam where the Buddhist landscape is now being shaped by the combined Vietnamese and Westernized Buddhism that is focused more on the meditative practices.[29]

After a 39-year exile, Thich Nhat Hanh was permitted to visit Vietnam in 2005. In November 2018, he returned to Vietnam to his "root temple", Từ Hiếu Temple, near Huế,[30] where he lived until his death on January 22, 2022, at the age of 95.[31]

Practice

According to Cuong Tu Nguyen & A. W. Barber, followers in Vietnam practice differing traditions without any problem or sense of contradiction.[32]

Nguyen, et al, also state that gaining merit is the most common and essential practice in Vietnamese Buddhism with a belief that liberation takes place with the help of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Buddhist monks commonly chant sutras, recite Buddhas’ names (particularly Amitābha), doing repentance and praying for rebirth in the Pure Land.[33]

The Lotus Sutra and the Amitabha Sutra are the most commonly used sutras.[34] Most sutras and texts are in Classical Chinese and are merely recited with Sino-Xenic pronunciations, making them incomprehensible to most practitioners.

Three services are practiced regularly at dawn, noon, and dusk. They include sutra reading with niệm Phật and dhāraṇī recitation and kinh hành (walking meditation). Laypeople at times join the services at the temple and some devout Buddhist practice the services at home. Special services such as Sam Nguyen/Sam Hoi (confession/repentance) takes place on the full moon and new moon each month. Niệm Phật practice is one way of repenting and purifying bad karma.[32]

Branches

Mahāyāna traditions

The overall doctrinal position of Vietnamese Buddhism is the inclusive system of Tiantai, with the higher metaphysics informed by the Huayan school (Vietnamese: Hoa Nghiêm); however, the orientation of Vietnamese Buddhism is syncretic without making such distinctions.[16] Therefore, modern practice of Vietnamese Buddhism can be very eclectic, including elements from Thiền (Chan Buddhism), Thiên Thai (Tiantai), Tịnh độ Pure Land Buddhism, and popular practices from Vajrayana.[16]

According to Charles Prebish, many English language sources contain misconceptions regarding the variety of doctrines and practices in traditional Vietnamese Buddhism:[35]

We will not consider here the misconceptions presented in most English-language materials regarding the distinctness of these schools, and the strong inclination for "syncretism" found in Chinese and Vietnamese Buddhism. Much has been said about the incompatibility of different schools and their difficulty in successfully communicating with each other and combining their doctrines. None of these theories reflects realities in Vietnam (or China) past or present. The followers have no problem practicing the various teachings at the same time.

Pure Land

The methods of Pure Land Buddhism are perhaps the most widespread within Vietnam. It is common for practitioners to recite sutras, chants and dhāraṇīs looking to gain protection through bodhisattvas or dharmapalas.[36] It is a devotional practice where those practicing put their faith in Amitābha (Vietnamese: A-di-đà). Followers believe they will gain rebirth in his pure land by chanting Amitabha's name. A pure land is a Buddha-realm where one can more easily attain enlightenment since suffering does not exist there.

Many religious organizations have not been recognized by the government; however, in 2007, with 1.5 million followers, the Vietnamese Pure Land Buddhism Association (Tịnh Độ Cư Sĩ Phật Hội Việt Nam) received official recognition as an independent and legal religious organization.[28]

Thien

| Editor's note: this section needs attention. Lacks citations |

Thiền is the Vietnamese form of Chinese Chan Buddhism (aka Zen Buddhism); in the West, Thiền is often referred to as "Vietnamese Zen." The traditional account is that in 580, an Indian monk named Vinitaruci (Vietnamese: Tì-ni-đa-lưu-chi) traveled to Vietnam after completing his studies with Sengcan, the third patriarch of Chan Buddhism. This would be the first appearance of Thiền. The sect that Vinitaruci and his lone Vietnamese disciple founded would become known as the oldest branch of Thiền. After a period of obscurity, the Vinitaruci School became one of the most influential Buddhist groups in Vietnam by the 10th century, particularly under the patriarch Vạn-Hạnh (died 1018). Other early Vietnamese Zen schools included the Vô Ngôn Thông, which was associated with the teaching of Mazu Daoyi, and the Thảo Đường, which incorporated nianfo chanting techniques; both were founded by Chinese monks.

A new Thiền school was founded by King Trần Nhân Tông (1258–1308); called the Trúc Lâm "Bamboo Grove" school, it evinced a deep influence from Confucian and Taoist philosophy. Nevertheless, Trúc Lâm's prestige waned over the following centuries as Confucianism became dominant in the royal court. In the 17th century, a group of Chinese monks led by Nguyên Thiều introduced the Ling school (Lâm Tế). A more native offshoot of Lâm Tế, the Liễu Quán school, was founded in the 18th century and has since been the predominant branch of Vietnamese Zen.

Some scholars argue that the importance and prevalence of Thiền in Vietnam has been greatly overstated and that it has played more of an elite rhetorical role than a role of practice.[37] The Thiền uyển tập anh (Chinese: 禪苑集英, "Collection of Outstanding Figures of the Zen Garden") has been the dominant text used to legitimize Thiền lineages and history within Vietnam. However, Cuong Tu Nguyen's Zen in Medieval Vietnam: A Study and Translation of the Thien Tap Anh (1997) gives a critical review of how the text has been used to create a history of Zen Buddhism that is "fraught with discontinuity". Modern Buddhist practices are not reflective of a Thiền past; in Vietnam, common practices are more focused on ritual and devotion than the Thiền focus on meditation.[38] Nonetheless, Vietnam is seeing a steady growth in Zen today.[29] Two figures who have been responsible for this increased interest in Thiền are Thích Nhất Hạnh and Thích Thanh Từ.

Theravada

| Editor's note: this section needs attention. Needs citations |

The central and southern part of present-day Vietnam were originally inhabited by the Chams and the Khmer people, respectively, who followed both a syncretic Śaiva-Mahayana (see History of Buddhism in Cambodia) and Theravada Buddhism. Đại Việt annexed the land occupied by the Cham during conquests in the 15th century and by the 18th century had also annexed the southern portion of the Khmer Empire, resulting in the current borders of Vietnam. From that time onward, the dominant Đại Việt (Vietnamese) followed the Mahayana tradition while the Khmer continued to practice Theravada.

In the 1920s and 1930s, there were a number of movements in Vietnam for the revival and modernization of Buddhist activities. Together with the re-organization of Mahayana establishments, there developed a growing interest in Theravadin meditation as well as the Pāli Canon. These were then available in French. Among the pioneers who brought Theravada Buddhism to the ethnic Đại Việt was a young veterinary doctor named Lê Văn Giảng. He was born in the South, received higher education in Hanoi, and after graduation, was sent to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to work for the French government.

During that time he became especially interested in Theravada Buddhist practice. Subsequently, he decided to ordain and took the Dhamma name of Hộ-Tông (Vansarakkhita). In 1940, upon an invitation from a group of lay Buddhists led by Nguyễn Văn Hiểu, he went back to Vietnam in order to help establish the first Theravada temple for Vietnamese Buddhists at Gò Dưa, Thủ Đức (now a district of Hồ Chí Minh City). The temple was named Bửu Quang (Ratana Ramsyarama). The temple was destroyed by French troops in 1947, and was later rebuilt in 1951. At Bửu Quang temple, together with a group of Vietnamese bhikkhus who had received training in Cambodia such as Thiện Luật, Bửu Chơn, Kim Quang and Giới Nghiêm, Hộ Tông began teaching Buddhism in their native Vietnamese. He also translated many Buddhist materials from the Pali Canon, and Theravada became part of Vietnamese Buddhist activity in the country.

In 1949–1950, Hộ Tông together with Nguyễn Văn Hiểu and supporters built a new temple in Saigon (now Hồ Chí Minh City), named Kỳ Viên Tự (Jetavana Vihara). This temple became the centre of Theravada activities in Vietnam, which continued to attract increasing interest among the Vietnamese Buddhists. In 1957, the Vietnamese Theravada Buddhist Sangha Congregation (Giáo Hội Tăng Già Nguyên Thủy Việt Nam) was formally established and recognised by the government, and the Theravada Sangha elected Venerable Hộ Tông as its first President, or Sangharaja.

From Saigon, the Theravada movement spread to other provinces, and soon, a number of Theravada temples for ethnic Viet Buddhists were established in many areas in the South and Central parts of Vietnam. There are 529 Theravada temples throughout the country, of which 19 were located in Hồ Chí Minh City and its vicinity. Besides Bửu Quang and Kỳ Viên temples, other well known temples are Bửu Long, Giác Quang, Tam Bảo (Đà Nẵng), Thiền Lâm and Huyền Không (Huế), and the large Thích Ca Phật Đài in Vũng Tàu.[39]

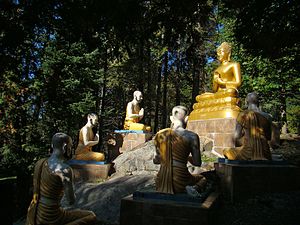

Gallery

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Cuong Tu Nguyen. Zen in Medieval Vietnam: A Study of the Thiền Uyển Tập Anh. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pg 9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Harvey 2012, p. 223.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Linh Hoang 2012, p. 20.

- ↑ Roof 2011, p. 1210.

- ↑ Schliesinger 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ Minh Mang (Wikipedia)

- ↑ Mekong Delta in Detail (Lonely Planet)

- ↑ Vietnam History (Lonely Planet)

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ T'oung Pao: International Journal of Chinese Studies. 1958. p. 185

- ↑ The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalog (T 232)

- ↑ Keyes, 1995, pp.78–82

- ↑ Nguyen Tai Thu. The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. 2008.

- ↑ Tai Thu Nguyen (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. CRVP. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-56518-098-7.

- ↑ Tai Thu Nguyen (2008). The History of Buddhism in Vietnam. CRVP. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-56518-098-7.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Prebish, Charles. Tanaka, Kenneth. The Faces of Buddhism in America. 1998. p. 134

- ↑ Nguyen Tai Thu 2008, pg 77.

- ↑ Nguyen Tai Thu 2008, pg 75.

- ↑ Nguyen Tai Tu Nguyen 2008, pg 89.

- ↑ Việt Nam: Borderless Histories – Page 67 Nhung Tuyet Tran, Anthony Reid – 2006 "In this first formal attack in 1370, a Confucian official named Lê Quát attempted, without much success, to brand Buddhism as heretical and to promote Confucianism. Times had drastically changed by Ngô Sĩ Liên's Lê dynasty."

- ↑ The Vietnam Review: Volume 3 1997 "Buddhism The close association between kingship and Buddhism established by the Ly founder prevailed until the end of the Trân. That Buddhism was the people's predominant faith is seen in this complaint by the Confucian scholar Lê Quát ."

- ↑ Elise Anne DeVido. "Buddhism for This World: The Buddhist Revival in Vietnam, 1920 to 1951, and Its Legacy." in Philip Taylor (ed), Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2007, p. 251.

- ↑ Gettleman, pp. 275–76, 366.

- ↑ Moyar, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ "South Viet Nam: The Religious Crisis". Time. 1963-06-14.

- ↑ Tucker, pp. 49, 291, 293.

- ↑ Maclear, p. 63.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Pure Land Buddhism recognised by Gov’t." Viet Nam News. December 27, 2007. Accessed: April 7, 2009.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Alexander Soucy 2007.

- ↑ "Thich Nhat Hanh Returns Home". Plum Village. November 2, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-11-02. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ↑ Joan Duncan Oliver (January 21, 2022). "Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Master, Dies at 95". Tricycle. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Cuong Tu Nguyen & A. W. Barber 1998, pg 135.

- ↑ Cuong Tu Nguyen & A. W. Barber 1998, pg 134.

- ↑ Cuong Tu Nguyen & A. W. Barber 1998, pg 134 .

- ↑ Prebish, Charles. Tanaka, Kenneth. The Faces of Buddhism in America. 1998. p. 135

- ↑ Cuong Tu Nguyen 1997, p. 94.

- ↑ Alexander Soucy. "Nationalism, Globalism and the Re-establishment of the Trúc Lâm Thien Sect in Northern Vietnam." in Philip Taylor (ed), Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post Revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2007; Cuong Tu Nguyen 1997, pg 342-3 [1]

- ↑ Alexander Soucy 2007; Cuong Tu Nguyen & A. W. Barber 1998.

- ↑ Theravada Buddhism in Vietnam

Sources

- Nguyen, Cuong Tu & A. W. Barber. "Vietnamese Buddhism in North America: Tradition and Acculturation". in Charles S. Prebish and Kenneth K. Tanaka (eds) The Faces of Buddhism in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Nguyen, Cuong Tu. Zen in Medieval Vietnam: A Study of the Thiền Uyển Tập Anh. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

- Linh Hoang (2012), Rebuilding Religious Experience: Vietnamese Refugees in America, AV Akademikerverlag

- Nguyễn Tài Thư (2008), History of Buddhism in Vietnam, Cultural heritage and contemporary change: South East Asia, CRVP, ISBN 1565180984

- Soucy, Alexander. "Nationalism, Globalism and the Re-establishment of the Trúc Lâm Thien Sect in Northern Vietnam." Philip Taylor (ed). Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Singapore, 2007

Further reading

- DeVido, Elise A. (2009). The Influence of Chinese Master Taixu on Buddhism in Vietnam, Journal of Global Buddhism 10, 413-458

- Buswell, Robert E., ed. (2004). "Vietnam", in Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 879-883. ISBN 0-02-865718-7.

External links

| This article includes content from the September 2018 revision of Buddhism in Vietnam on Wikipedia ( view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |