Sir Ernest Shackleton: The Great Irish Antarctic Explorer

Updated On: May 14, 2024 by Ciaran Connolly

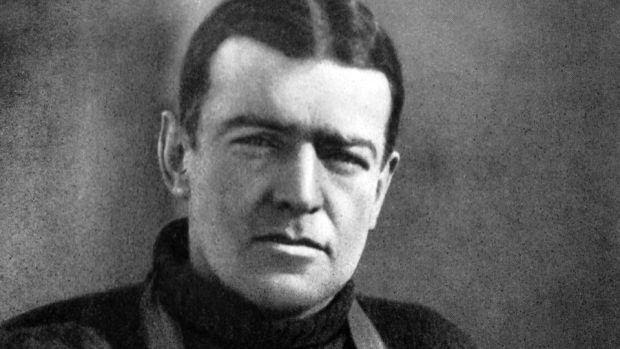

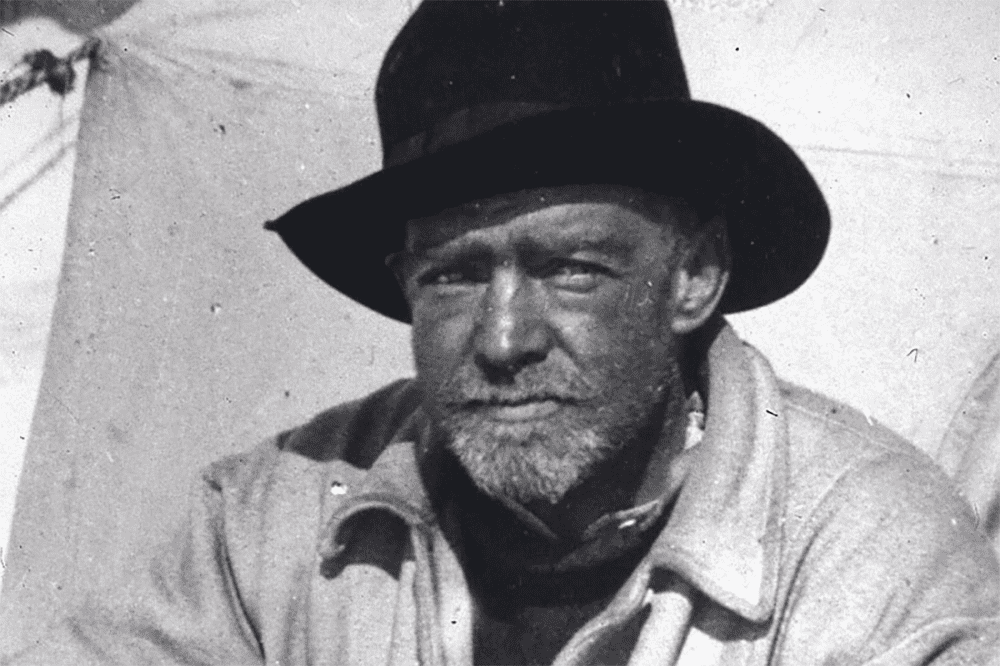

Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874 – 1922) was an Irish explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic over one hundred years ago. He is one of the most influential figures in the Heroic Age of the Antarctic Expedition, which began at the end of the 19th century and ended after World War I.

The era was launched in 1895 when the Sixth International Geographical Congress meeting in London declared: ‘that this Congress record its opinion that exploring the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken. Because the additions to knowledge in almost every branch of science would result from such an exploration, the Congress recommends that the scientific societies worldwide should urge, in whatever way seems most effective, that this work should be undertaken before the close of the century’.

Following this declaration, the Antarctic continent became the focus of worldwide efforts, resulting in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, launching seventeen different investigations from ten countries. Due to limited resources in knowledge and equipment, each expedition became a coup of perseverance that challenged the explorers’ physical and mental limitations. Each expedition became a small victory in itself, regardless of the outcome.

As a pioneer of this ground-breaking scientific and historically significant movement, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s name, according to Roald Amundsen, ‘will evermore be engraved with letters of fire in the history of the Antarctic’.

Early Life of an Explorer

Ernest was born on 15 February 1874 in Kilkea, County Kildare, Ireland. He was the second of ten children born to Henry and Henrietta Shackleton and is not the only one of the Shackleton children to have a claim to fame: his brother Frank was a major suspect in the theft of the Irish Crown Jewels in 1907.

Ernest’s father was a long-time landowner who grew restless and decided to pursue a career in medicine. He began his studies at Trinity when Ernest was six. This prompted the family to move to London four years later so Henry could find work, and although he lived a great deal of his life in England, Henry took pride in his Irish roots and constantly referred to himself as an Irishman.

Ernest was a steadfast student with a ferocious passion for reading, a hobby that would later feed his thirst for adventure. Despite being highly intelligent – he finished 5th place in a class of 31 –Ernest found the rigid structure of traditional academia suffocating. His father tried to persuade him to follow in his footsteps and study medicine, but Ernest resisted. Instead, he joined the merchant navy at sixteen. Although his father disapproved, he helped secure Ernest a place on a square-rigged sailing ship called Hoghton Tower.

Sea life suited Ernest. He found his thirst for adventure satisfied, for now, with all the fascinating new places he could travel to, and he realised he could fit comfortably in with men from all walks of life. During his four years at sea, Ernest qualified as a Second Mate and assumed a post as a Third Officer on a tramp steamer. In 1896, he was granted First Mate status, and by 1898, he was certified as a Master Mariner, which qualified him to command any British ship anywhere in the world.

Ernest Shackleton’s Journey: Discovery Expedition (1901 – 1903)

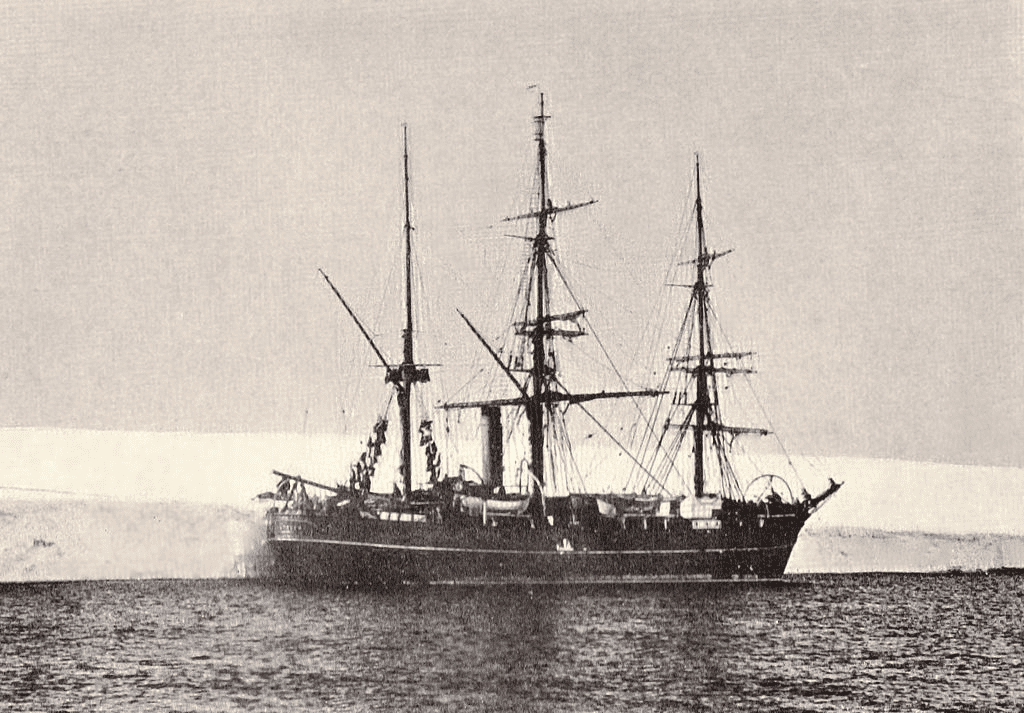

Ernest’s fortunes changed in 1900 when he met army Lieutenant Cedric Longstaff aboard the Tinagel Castle. A fond acquaintanceship ensued, and Ernest soon discovered that Longstaff’s father was Llewellyn W. Longstaff, the leading financial backer of the National Antarctic Expedition being organized in London. Longstaff was impressed by Ernest’s passion at his interview, and he was quickly appointed as the Third Officer aboard Discovery, the expedition’s ship. British Naval Officer and renowned explorer Robert Falcon Scott joined him.

Discovery set sail in July 1901 and arrived at the Antarctic Coast on 8 January 1902. This was the first time anyone had been this close to the South Pole in human history. While the expedition was mostly for exploratory and scientific purposes, Ernest also took part in an experimental balloon flight. He embarked on the first sledging trip, establishing the first safe route to the Great Ice Barrier, now known as the Ross Ice Shelf.

The trip’s ending was not so prosperous. 22 sledge dogs fell fatally ill after ingesting tainted food, and the Discovery’s crew suffered from frostbite, snow blindness and scurvy.

Once back in England, Ernest realised his health was declining, so he pursued a different career path (at least for a while): journalism. Whilst on board the Discovery, Ernest found he had a knack for it when he began editing the expedition’s magazine, The South Polar Times.

He initially worked for the Royal Magazine, but finding it inadequate, he accepted a sectary position with the Royal Scottish Geographical Magazine, which suited his taste for adventure and discovery. During this time, Ernest met his wife and the mother of his three children, Emily Dorman. Emily was a friend of Ernest’s sister and would become a crucial part of Ernest’s career as an explorer by using her social connections to create practical and financial support for her husband’s work.

Nimrod Expedition (1907 – 1909)

Ernest’s next expedition was aboard the Nimrod in 1907. It left Lyttleton Harbour, New Zealand, on 1 January 1908, intending to reach the South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole. Having learned from previous expeditions, the ship was towed 1,650 miles by the steamer Koorya to conserve coal.

Since their last visit, the Great Ice Barrier’s inlet had expanded to form a large bay full of whales! It was aptly christened the Bay of Whales.

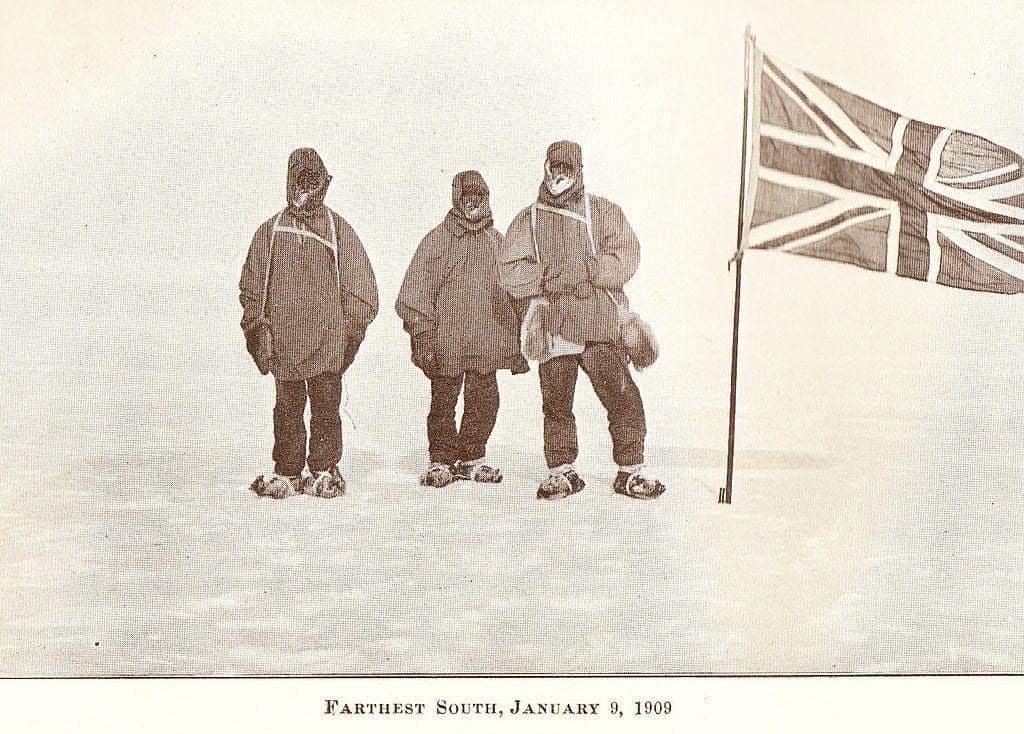

After difficulties sustaining a base due to unstable ice conditions, The Nimrod eventually established a base at Cape Royds and, on 29 October 1908, left to embark upon its Great Southern Journey. It reached the farthest South latitude at the time – 88° 23′ S – only 112 miles from the Pole. This journey allowed Ernest to discover Beardmore Glacier – named for one of Ernest’s patrons – and launch numerous firsts: the first people to see and travel on the South Pole Plateau, the first ascent of Mount Erebus, and the discovery of the approximate location of the South Magnetic Pole.

Ernest was greeted with public acclaim when he returned to the UK. He was received by King Edward VII on 10 July, who raised him to a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. He was officially knighted that November, becoming Sir Ernest Shackleton. He was also honoured by the Royal Geographical Society, which bestowed him a Gold Medal.

During this period, Ernest published Heart of the Atlantic, made three recordings on an Edison phonograph, and began a lecture tour where he discussed his expeditions and those of Scott and Roald Amundsen. He seemed satisfied not to travel again, writing to his wife Emily: ‘I am never again going South and I have thought it all out and my place is at home now’.

Imperial Trans-Atlantic Expedition (1914 – 1917)

This did not last long. Ernest soon published an article aimed at narrowing down ideal candidates to join him on his latest expedition: an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic Continent, which Ernest declared was ‘one great main object of Antarctic journeyings’. The expedition was funded mainly by private donations and a grant of £10,00 from the British government (£900,00 in today’s economy).

Public interest was at an all-time high, with over 5000 applications to join! Ernest was unconventional in his hiring techniques: he insisted that temperament and character were just as important as qualifications and technical ability for an expedition like this. He also disagreed with the traditional hierarchies promoted by other ships and instead actively chose to socialise with his crew regularly and fairly allocate chores to men of all ranks.

Two ships were launched as part of this expedition. The Endurance would carry the main party into Wendell Sea, aiming for Vahsel Bay, where a team of six, led by Ernest, would begin the crossing of the continent, and the Aurora with a backing party led by Captain Aeneas Mackintosh on the opposite side of the continent.

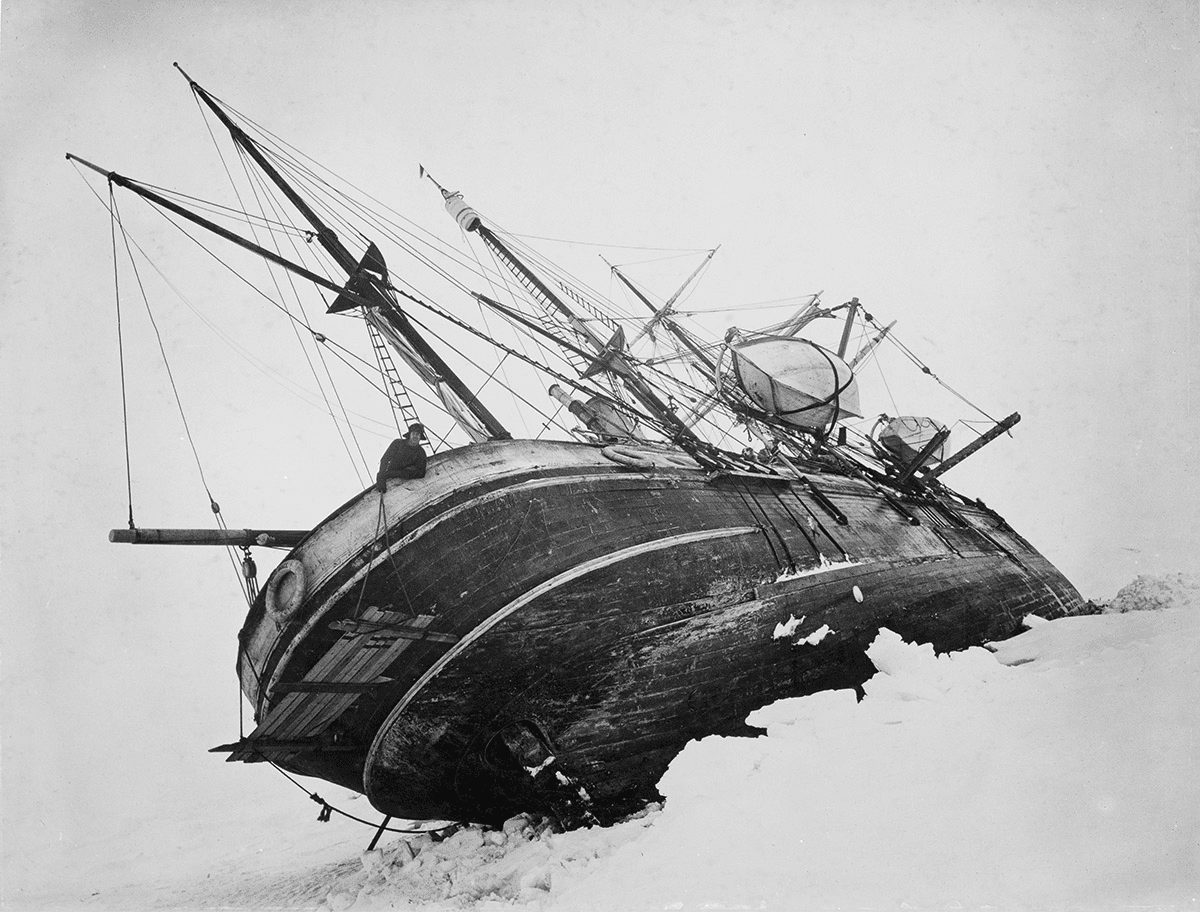

The Endurance was lost early in the expedition. Having set off from South Georgia on 5 December, heading for Vahsel Bay, the ship encountered first-year ice (frozen sea water which floats on the water’s surface) the closer south it travelled. It tried to persevere but was ultimately lost when it became lodged in an ice floe; otherwise known as drift ice or brash ice, this kind of ice is not attached to the shoreline or any fixed object like grounded icebergs or shoals, and as a result, is carried along by winds and sea currents.

Ernest had hoped to salvage the ship, so he instructed his crew to abandon their routine until the ship was loose enough for them to escape. They were stuck there until the Spring, and unfortunately, the breaking up the ice floe placed significant pressure on the Endurance’s hull. Ernest and his crew abandoned the ship when water began to seep into the lower parts of the ship.

Ernest and his crew temporarily camped on a large flat floe for almost two months. They then moved to a larger one, which they christened Patience Camp, hoping it would float towards Paulet Island. However, disaster struck when it split, and Ernest and his crew were forced into their lifeboats. After five days at sea, they arrived on Elephant Island, their first time on solid ground for 497 days.

On 24 April 1919, their strongest lifeboat, the James Caird, was launched to find help and return for the remainder of the crew. It battled stormy seas for 15 days, almost capsizing numerous times, and had to ride out a significant storm off-shore from South Georgia; this was perhaps a miracle, given that the same hurricane sunk a 500-ton steamer.

Reaching land, Ernest and two crew members trudged 32 miles across mountainous terrain to reach a whaling station at Stromness. The rest of the crew were eventually rescued. This expedition cost the lives of three men.

The Death and Legacy of Ernest Shackleton, Explorer

After a few more years on the lecture circuit, Ernest grew restless and decided to explore again. His initial plan for his Shackleton-Rowett expedition was the Beaufort Sea area of the Arctic, but his destination became the Antarctic, aiming for an in-depth oceanographic study. Ernest Shackleton was an explorer once again.

Before the expedition, Ernest suffered a heart attack whilst in Rio de Janeiro. Against the wishes of his family, friends, and colleagues, Ernest refused medical examination and continued to South Georgia.

On the morning he arrived at South Georgia, Ernest summoned the expedition’s doctor, Alexander Macklin, to his cabin, complaining of back pains and other undisclosed discomforts. Deeply concerned, Macklin suggests Ernest give up alcohol, his Achilles heel. Just moments later, at 2.50 am on 5 January 1922, Shackleton suffered another heart attack that he did not survive. Ernest was buried in South Georgia at the request of his wife Emily.

Dozens of books have been published about Sir Ernest Shackleton, detailing his life and incredible discoveries. He was listed as 11th in the BBC’s 100 Greatest Britons poll.

He is still admired today for his renowned leadership qualities. The University of Exeter has an entire course about Ernest’s leadership at their Centre for Leadership Studies; Shackleton’s Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer wrote that he ‘resonates with executives in today’s business world. His people-centred approach to leadership can guide anyone in a position of authority, and a ‘Shackleton School’ was set up in Boston on ‘Outward Bound principles with the motto ‘The Journey is Everything’. His memory is treasured by explorers today.

County Kildare Council erected a statue in Athy in Ernest’s honour in 2016.