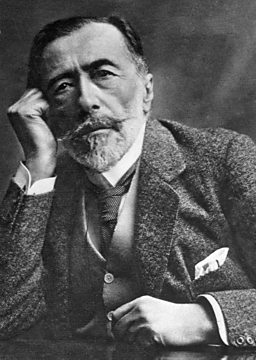

The Secret Agent: Joseph Conrad's radical tale of terror

13 July 2016

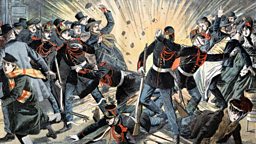

With a new BBC adaptation starring Toby Jones and Vicky McClure beginning on Sunday 17 July, Joseph Conrad's classic thriller The Secret Agent suddenly feels very of-the-moment. Penned in the early 20th century, this tale of radicalised individuals, suicide bombers and shadowy espionage activities feels like it could have been written yesterday. With our age practically defined by acts of terror, Conrad's fin de siècle story, with its paranoia and its enemies within, holds a mirror up to our deepest fears. BRIAN MORTON explores this vanished epoch and finds it instantly, and sadly, all too familiar to our own.

An idiot boy, with compass and pencil, drawing endless circles on a sheet of paper: there could hardly be a simpler or more graphic representation of Joseph Conrad’s theme and message in The Secret Agent.

It is a book of ciphers, in the sense of emptinesses, and the circles drawn by the hapless Stevie, while revolution and the overthrow of the social order are plotted in the next room, stand well both for the interlocking lives of the book’s characters and for their self-enclosed distance from one another.

Conrad’s revolutionaries are barely human, physically repulsive, eloquent in an ideology that seems to go nowhere

It is said that sales of The Secret Agent rose sharply after the 9/11 attacks on New York City, as if the book offered insight into the mind-set of incendiary politics and the suicide bomber.

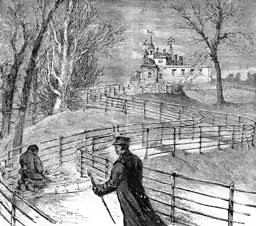

In fact, it’s a novel that uses an actual attempt in 1894 to blow up the Greenwich Observatory as a narrative device to explore a society which Conrad, a Polish émigré and former sailor, viewed very much from the outside, even as he inhabited its language with more than native precision.

T. S. Eliot also referred to the Greenwich bomber – as “Boudin” rather than Bourdin – in a poem called “Animula” written 20 years later, and seven after the publication of his own The Waste Land, which also seems to revive the spirit of Conrad’s bleak 1907 satire: all those seedy characters trying to make a connection, and falling short.

The Secret Agent is sometimes adduced as an example of what is misleadingly called, following Hannah Arendt, “the banality of evil”. There are no saintly Prince Kropotkins among Conrad’s plotters, or from fiction any version of the radiant Christina Light or Paul Muniment in Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima, which also has a setting of radical politics.

Instead, Conrad’s revolutionaries are barely human, physically repulsive, eloquent in an ideology that seems to go nowhere but back to its own premises.

Arguably the book’s central character, Mr Verloc sells packages of condoms and titty books alongside radical journals with titles like Torch and Gong. And not only is he a pornographer, but also a police spy, in confirmation that his stepbrother’s circles are always bedded one within the other and intersect at unexpected points.

He keeps a live bomb on his person at all times and clutches its trigger, determined never to be taken alive or without taking a policeman with him

If Verloc is the central character, the provocateur charged with engineering an event that will heighten security across the enervated capital, then the Professor is the most sinisterly comic.

He keeps a live bomb on his person at all times and clutches its trigger, determined never to be taken alive or without taking a policeman with him. And yet the indiarubber ball he holds in his pocket suggests self-abuse as much as fanaticism.

But again Conrad isn’t so much concerned with the psychology of the suicide bomber, however of the moment such a possibility might seem. In suggesting that ideology is a form of masturbation, Conrad seems to be reinforcing his view, expressed quite explicitly in the early pages of The Secret Agent, that it is not ideas but made and useful things that form society.

When the English lawyer and novelist Alan Burns published The Angry Brigade in 1973, he was equally praised and condemned for his accurate rendition of dissident voices in British society. Thirteen years after first publishing The Secret Agent Conrad felt a need to step forward and justify his portrayals by saying that he had received many communications from ex-radicals saying, in effect, “yes, we were exactly like that”.

In fact, Burns’s “tape-recorded” testimonies were entirely fictional and not based on specific research, while Conrad’s revolutionaries are a compound of dockyard chatter and high-society gossip, his revolutionaries mere toothless cogs in a dysfunctional machine. The only victims are the innocent, the only potent loyalties those of family and blood.

Conrad has a curious history on screen. He stands behind the maniac Col Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, though Coppola’s epic is by no means a straightforward dramatisation of Heart of Darkness.

He’s referenced obliquely but tellingly in Alien where the squabbly freighter that houses the creature that will destroy civilisation is called the Nostromo. The novel of that name was the subject of an Anglo-Italian adaptation in 1997 and screened on BBC Two.

We understand more about Conrad’s world now because we live in a latter-day version of it, blooded by terrorism and by the fear of terrorism

The Secret Agent was filmed a year before, with Bob Hoskins as Verloc and with Patricia Arquette, Gerard Depardieu, Eddie Izzard, Jim Broadbent and Christian Bale all in the cast.

The challenge, not quite met by Christopher Hampton’s script, was to convey Conrad’s characters - and that includes the worn policeman Heat, who should be the book’s moral centre but somehow isn’t – with the right mix of caricatural savagery and human depth.

We understand more about Conrad’s world now because we live in a latter-day version of it, blooded by terrorism and by the fear of terrorism, caught up in a bonfire of the old ideologies, each of us nervously guarding our circles of society and anxiously negotiating our intersections with others.

That’s the world Conrad portrays and this is the world his revolutionaries, who also stand for above-ground politicians, bankers, businessmen and the poor bloody infantry that make up the social majority, shabbily inhabit.

One of Conrad's characters, Yundt, not a man of action or even an inspiring orator, epitomises this world: “With a more subtle intention, he took the part of an insolent and venomous evoker of sinister impulses which lurk in the blind envy and exasperated vanity of ignorance, in the suffering and misery of poverty, in all the hopeful and noble illusions of righteous anger, pity and revolt.”

The Secret Agent, a three-part adaptation of Conrad's novel, will be broadcast on Sunday 17 July, 21:00, BBC One.

Clip: Plotting an act of terror

"Blow up the Observatory?"

Vladimir instructs Verloc to plant a bomb in the Greenwich Observatory.

Secret agents on BBC Books

Related Links

More from Books

-

![]()

#Vote100Books

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

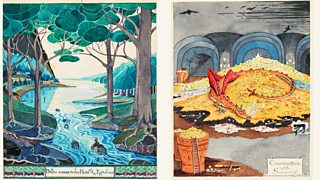

Middle-earth in colour

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

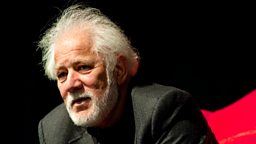

Neil Gaiman

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Publishing design cliches

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms