Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870). The Youth of Impressionism.

Scène d'été, 1869

Cambridge, Massachusetts, Fogg Art Museum

© President and Fellows of Harvard College / DR

Portrait de Bazille à la Ferme Saint-Siméon, 1864

Montpellier, musée Fabre

Don de Frédéric Bazille, neveu de l'artiste, 1945

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

The 1860s were without doubt some of the most critical years in the history of art. During this period, a small group of independently-minded artists, including Manet, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, and Cézanne, set their sights on modernising painting and blazed new trails.

Among their number was the Montpellier-born artist Frédéric Bazille.

Although we are familiar with his personality from his extensive surviving correspondence, his part in the genesis of “New Painting” (Duranty) has often been downplayed to that of a dilettante fellow traveller and occasional source of practical support for budding Impressionist painters.

In the words of his friend Edmond Maître, shortly after his death in combat in 1870: “Bazille was the most gifted, and the most pleasant, in every sense of the word.”

Bazille’s training as an artist was disrupted by medical studies, but in a career spanning a mere seven years he produced a large number of masterpieces on a par with the work of his more precocious friends.

He wrestled with often conflicting desires – meeting the expectations of his middle-class family and playing a part in the artistic revolution which was taking place – and his originality has its roots in the combination of his Protestant Languedoc background and passionate nature.

Frédéric Bazille, en 1867

Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Legs de Marc Bazille, 1924

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

His work bears the hallmarks of youth – it is ambitious, inventive, idealistic and rebellious and each new painting represents a challenge, a triumph or a failure. According to Bazille: “I sincerely hope that if I achieve anything, it will at least have the merit of being unlike anyone else”.

Bazille’s work is pervaded by the powerful light of the landscapes of his native southern France, but also by the shadow cast by his doubts and the inertia induced by his melancholy.

Frédéric Bazille’s brief life, which was divided between the seething ferment of artistic life in Paris in the winter and lazy summers in the Languedoc, has finally secured the much deserved recognition of an international retrospective.

This exhibition, which is the first to be organised by a French national museum, is a collaboration between the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Trois études de loups

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Thierry Le Mage

FROM MONTPELLIER TO PARIS

Frédéric Bazille was born into an upper middle-class Protestant family in Montpellier in 1841. His father was Deputy Mayor of Montpellier and later became a Republican Senator for the Hérault département and president of the Agricultural Society, which made him an important figure in Languedoc wine-producing circles.

Frédéric was the eldest son and a career in medicine was mapped out for him. However, he also learned to draw at the studio of sculptors Baussan senior and junior.

In Montpellier, the young man was fortunate to be introduced to fine collections of paintings at the Musée Fabre, considered to be among the best in France, and the exceptional collection of modern paintings which art enthusiast Alfred Bruyas began to build up in the early 1850s.

As a neighbour, Frédéric visited the private museum in the Bruyas town house, which was very close to the Bazille family home, and studied the latest masterpieces by Delacroix and Courbet.

In 1862, at the age of twenty, Bazille left Montpellier to pursue his medical studies in Paris. As soon as he arrived there, he enrolled at the studio run by the Swiss painter Charles Gleyre, where he met Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley.

In 1864, Bazille’s parents agreed to let him drop his medical studies and pursue a career as an artist. He also left Gleyre’s studio and henceforth painted independently in his own studio or with Monet.

Paysage de montagnes boisées

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Michel Urtado

SUR LE MOTIF

In the spring of 1863, Monet felt the urge to paint sur le motif, or in nature, and took Bazille and other friends from Gleyre’s studio to Fontainebleau Forest.

Just like the painters of the Barbizon school before them, who had enjoyed taking refuge in the forest and painting the beauties of nature, they took their easels outside to paint studies. Their approach represented a departure, however, from the pantheistic visions of their predecessors Rousseau, Diaz and Corot.

Like photographers, they framed the landscape in a quick snapshot and focused purely on depicting its colours and contrasts. Bazille improved his eye and technique under the tuition of the more experienced artist Monet.

The two young men travelled together on several occasions, including in the spring of 1864, when they made a trip to Normandy to visit Monet’s family in Le Havre and La Ferme Saint-Siméon in Honfleur, which often also played host to Boudin and Jongkind.

In August 1865, Bazille joined Monet in Chailly to pose for his huge painting Luncheon on the Grass (Paris, Musée d’Orsay). He took advantage of the trip to paint a few landscapes and also to depict his friend, who was confined to bed following an accident, in the work The Improvised Field Hospital .

After this trip, Bazille asserted his independence in symbolic terms from Monet and forsook the landscapes of northern France in favour of exploring those of his native Languedoc.

L'Atelier de la rue de Furstenberg, 1865

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

STUDIO FRIENDSHIPS

As soon as he arrived in Paris, Bazille pestered his parents for a studio in which to work. The artist occupied six studios between 1863 and 1870.

Three of them are featured in interiors which are all indirect self-portraits depicting the new life as an artist which he relished.

Bazille, who received an allowance from his parents, was generous to his friends and shared several of his apartments with them.

In 1864, Bazille and Monet moved into the rue de Furstenberg together; in 1867, he shared lodgings in the rue Visconti with Renoir – and occasionally Monet and Sisley.

In the studio, the artists, and friends who were passing through, worked with professional female models or posed for each other when funds were short.

In early 1868, Frédéric Bazille moved into a more spacious studio with Renoir in the rapidly developing Les Batignolles district, not far from the Café Guerbois – haunt of the realist avant-garde including Fantin-Latour, Degas, Manet, and also the writers Zola, Astruc and Duranty.

Bazille painted a view of his own studio featuring his friends, echoing A Studio at Les Batignolles by Fantin-Latour (Paris, Musée d’Orsay). Bazille, who was painted in the centre of the picture by Manet, was now an integral part of the circle of “actualistes”, as they were dubbed by Zola.

Nature morte au héron, 1867

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

HUNTING TROPHIES

In a letter to his mother requesting money to pay live models, Bazille writes: “Do not condemn me to still lifes forever!” The still life genre could be viewed as the preserve of penniless artists. However, the choice of this genre was not entirely motivated by financial considerations. Still lifes were an easy medium for young artists to practice the art of composition and the depiction of textures and volumes. The genre enjoyed a revival under the Second Empire as a result of middle-class patronage.

Bazille made his first appearance at the Salon in 1866 with a painting entitled Still Life with Fish. This dark, detailed work betrays the influence of the Dutch and Flemish masters, but also of Manet. The artist’s fine Still Life with Heron demonstrates both his love of hunting, which he enjoyed with his father in the vicinity of Montpellier, and the popular influence of hunting trophies by Oudry and Chardin, whose discreet lyricism and elegant simplicity were rediscovered under the Second Empire. Far from restricting their scope to a single speciality, Bazille and his friends were eager to modernise every genre and reinterpret tradition in order to free themselves from its hold more effectively.

L'atelier de Bazille (détail), 1870

Musée d'Orsay

Legs Marc Bazille, 1924

© Musée d’Orsay, dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Bazille and music

Bazille’s other great passion after painting was music.

He inherited his musical talent from his mother and was a keen piano player. This was the only way to enjoy music other than in concert halls, and was Bazille’s main source of entertainment in Paris.

“I am very impatient for my piano to arrive safely and beg you to send me as much music as you can, my symphonies for four hands, Chopin waltzes, Beethoven sonatas and the Gluck score [...]. When I have some money to spare, I will buy Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words.” (Bazille to his mother, December 1863).

Bazille later shared a passion with his friend Edmond Maître for Berlioz and German composers Schumann and Wagner, who were not very well known or popular in France at the time. Bazille enjoyed live entertainment: he frequented theatres and attended concerts at the Conservatoire and Opera House whenever he could afford to. At the Théâtre Lyrique, he admired Bizet’s Pearl Fishers (1863), The Trojans by Berlioz (1863) and Wagner’s Rienzi (1869): “the youthful work of a man of genius”. Although Bazille’s paintings favour realist modernity in which emotions have no place, his musical tastes reveal, by contrast, his romantic and passionate nature.

Jeune fille au piano, 1865-1866

© C2RMF Bruno Mottin

“A young girl playing the piano and a young man listening to her”

In 1866, Bazille embarked on a large canvas (1.5m x 2m) for his first submission to the official Salon, featuring a subject very close to his heart: “A young girl playing the piano and a young man listening to her”.

This painting, which was rejected by the Salon jury and was previously believed to have been lost or destroyed, has been detected “beneath” a later composition using x-ray technology.

The touch-screen digital facility in this room allows visitors to discover this “missing link” in Bazille’s work.

With the help of the Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (C2RMF), the laboratories at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and other American museums, several works have been x-rayed and a dozen other lost compositions have been rediscovered.

When Bazille was dissatisfied with his work or short of funds, he regularly recycled used canvases to paint new pictures.

Les Remparts d'Aigues-Mortes, du côté du couchant, 1867

Washington, National Gallery of Art

Collection de M. et Mme Paul Mellon

© Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, NGA Images

Aigues-Mortes

In the early summer of 1866, Bazille expressed a desire to visit Aigues-Mortes, the medieval city from which St Louis set off on his crusade and a major historical memorial site for Protestants.

Gaston Bazille warned his son about the fevers and insalubrious conditions in the city during the “heat of August” and added “I have never seen a painting of Aigues-Mortes.”

In late May 1867, the artist finally made a trip there: “It is a beautiful day and I am setting off later. I have started work on three or four landscapes in the vicinity of Aigues-Mortes. I am going to paint the city walls reflected in the lagoon at sunset on my large canvas. It will be a very simple painting and should not take very long.”

Bazille brought home a large number of sketches and three canvases from this painting expedition. The artist had embraced Monet’s technical advice and now painted en plein air around the Camargue lagoon with a sure touch. The austere splendour of the site, the geometric rigour of the ramparts and the luminous yet melancholy atmosphere are wonderfully rendered by Bazille. Alone and far from already over-popular locations in Île-de-France and Normandy, Bazille was able to express his personality in the heart of his home territory.

Vue de village, 1868

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

“PAINTING FIGURES IN THE SUN”

Doubtless taking The Meeting by Courbet (Musée Fabre) in the Bruyas collection as his reference point, Bazille turned very early to the idea of “painting figures in the sun”, as he wrote in December 1863.

This new unapologetically modern genre, which falls between portraiture and genre scenes, also appealed to Monet, Renoir and Berthe Morisot, who set themselves the challenge of introducing modern figures into landscapes painted sur le motif.

Bazille addressed this issue with The Pink dress in 1864, when he also depicted his family’s Domaine de Méric estate for the first time.

Every summer he painted his most ambitious works destined for the next Salon there, including Family Reunion and View of the Village , which according to Berthe Morisot, fulfilled the aspiration of this entire generation “to place a figure en plein air”. Over the course of a decade, this technical exercise became the trademark of the new school.

Although Monet failed to exhibit at the Salon, Bazille’s paintings were accepted on a regular basis. Duranty wrote in 1870: “Every spring Monsieur Bazille returns from the South with summer paintings [...] full of greenery, sunshine and simple assurance”.

Astruc also credited Bazille with playing a key role in the quest to capture “the astonishing fullness of light and the unique impression of the outdoors and the power of daylight”.

La toilette, 1870

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

THE MODERN NUDE

The academic nude featured prominently on the walls of the Salons of the 1860s. The surprisingly immodest bodies of Venuses rubbed shoulders with virile heroes with bulging muscles. Alexandre Cabanel, who hailed like Bazille from Montpellier, experienced great success with his nudes which perfectly captured middle-class fantasies.

However, following in the wake of Courbet, who blazed a trail by depicting realistic nudes in The Bathers (Musée Fabre) and The Wrestlers ( (Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts), , a few artists depicted the body naturally, even though this attracted criticism and led to rejection by the Salon.

Bazille established a reputation as a painter of the male body, a subject which was largely overlooked by his fellow artists. While exploring how to depict figures en plein air, the artist painted Fisherman with a Net as a companion piece to View of the Village for the Salon in 1869, and followed it up with Summer Scene the next summer.

After painting family scenes at Méric, Bazille gradually moved away from the house and immersed himself in the natural world on the banks of the river Lez, where he arranged these athletic, luminous bodies in the open air.

These bold paintings are among Bazille’s most original works – certains y ont lu l'expression d'un désir homosexuel sublimé with some critics viewing them as a manifestation of repressed homosexual desire – and they foreshadow Cézanne’s interest in the same theme. By contrast, the feminine nude of La Toilette is more reminiscent of a tribute to the Orientalism of Delacroix and the eroticism of Manet.

Jeune femme aux pivoines, 1870

Washington, National Gallery of Art

Collection de M. et Mme Paul Mellon

© Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, NGA Images

Flowers

Flower painting experienced a major revival under the Second Empire. Courbet, Manet, Fantin-Latour, Monet, and Renoir turned their hand to this commercial, middle-class genre with relish.

Bazille was attracted to the subject as he had studied many species in the botanical gardens adjacent to the Medical Faculty in Montpellier, and in the greenhouse at Méric in particular.

In pictures painted for the Salon or as presents for their circle of acquaintances, Bazille and his friends drew on old models but ignored the symbolism of flowers and the moral lessons traditionally associated with the genre.

What remained was the pleasure of painting studies from nature and using bold combinations of colour prompted by these cheerful bouquets.

Jeune femme aux pivoines, 1870

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

Bazille’s two versions of his Young Woman with Peonies , with flowers and a black model reminiscent of certain paintings by Manet, combine the still life genre with figure painting.

Painted in the spring of 1870, before the artist returned to Montpellier for the last time, these pictures are striking not only on account of their differences, but also due to the consummate technical mastery which Bazille has now achieved.

They demonstrate his predilection for serene figures absorbed in an activity or, by contrast, looking the spectator fearlessly in the eye.

Ruth et Booz, 1870

Montpellier, musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

IS BAZILLE A “HISTORY PAINTER”?

In May 1870, Bazille left Paris and his new studio in the rue des Beaux-Arts and went to Montpellier, where he spent his final summer. Disappointed by the mixed reception of his masterpiece Summer Scene at the latest Salon, the artist hid himself away in Méric.There he painted two new pictures, Landscape on the Banks of the Lez and Ruth and Boaz . They are the same size and may have been intended as companion pieces. With Landscape on the Banks of the Lez , Bazille scales the heights of classical majesty of Poussin and Corot, referring to it in his letters as an “Eclogue”, expressing the loneliness of the artist and the “the heat [which] makes everything evaporate and reigns calm and alone.”

With Ruth and Boaz , Bazille takes an unprecedented step away from the imperative to be luminous and realistic by drawing his subject matter from the Bible and the mystical lyricism of a poem by Victor Hugo.

The introduction of night-time and history into his art was accompanied by a movement towards a more synthetic style, which could possibly be attributed to the influence exerted by Puvis de Chavannes.

This final painting was not complete when Bazille, apparently dissatisfied with it, set aside his paintbrushes and enlisted to fight in the Franco-Prussian War. When the young man volunteered on 16 August 1870, he described himself as: “Bazille, Jean Frédéric, esquire, aged 28, history painter by trade”.

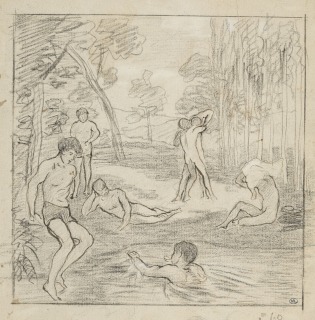

Etude pour la "Scène d'été", 1869

Paris, musée d'Orsay, conservé au département des Arts graphiques du musée du Louvre.

Don de Frédéric Bazille, neveu de l'artiste, 1948

© RF 29731

Bazille the draughtsman

Bazille, who learned to draw at Baussan’s studio in Montpellier and under Charles Gleyre in Paris, favoured primarily black crayon and graphite pencil. He did not draw much, but captured landscapes at Méric and Aigues-Mortes, the faces of family members, and everyday subjects in his sketchbooks.

The artist often framed his sketches with a rectangular border which marked out the proposed edges of the finished painting. Bazille thought mainly in terms of painting.

The artist made a few preparatory sketches for his large Salon paintings which reflected the broad lines of his composition and the spatial arrangement of the figures ( Family Reunion, Summer Scene ). Certain details such as faces and hands were worked out in specific studies.

The composition he sketched out was then divided up with a grid for transfer in enlarged form onto canvas ( The Pink Dress). Bazille’s career was cut short and he did not, therefore, leave behind an extensive body of drawings. With the exception of two sketch books gifted by his brother to the Louvre in 1921, only a dozen sheets are known to exist.

André Joubin et Marc Bazille devant la nouvelle présentation des tableaux de Frédéric Bazille au musée Fabre., 1919

Documentation du musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole - photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

“FRÉDÉRIC BAZILLE’S STAR HAS ONLY JUST STARTED TO SHINE”

On 16 August 1870, Bazille took the wholly unexpected step of enlisting in a Zouave regiment. Was this inspired by genuine patriotic fervour or was it a death wish? A desire to prove his worth to friends and family – and to himself – or a “diversion”?

Bazille seemed to grasp the opportunity presented by this military adventure as a means of resolving the personal crisis apparent in his last two pictures.

After spending several weeks in Algeria, the young man returned to France and was sent into action with his battalion in Besançon, and then in Beaune-la-Rolande near Orléans. He was killed during his first attack on 28 November.

At exactly the same time, Renoir was called up to join a Chasseur regiment, Monet fled to London with his family, and Cézanne went to ground in L’Estaque. Later on, Degas and Manet enlisted in the National Guard in Paris.

In 1874, the first exhibition of art by the Impressionist group was held in Paris; not a single work by Bazille was exhibited. The tragedy of 1870 cost Frédéric Bazille his life and marked the end of a chapter without parallel in the history of art – the birth of Impressionism.