José Rizal: Life and Works

Who Is José Rizal?

Dr. José Rizal (José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda in full) is an intellectual who fought for his country with his writing. His famous words “Ang kabataan ang pag-asa ng bayan” (“the youth is the hope of the future”), although cliche, remain relevant today.

Rizal began writing when he was quite young. You could say it was his first love. At only 14, he wrote the poem “To the Child Jesus,” demonstrating his early concern for Christianity and societal injustice. When he was 18 and still studying at the University of Sto. Tomas (UST), he participated in a poetry contest. He submitted a poem titled “To the Filipino Youth,” which he dedicated to the youth to encourage them to speak up about their beliefs rather than remain silent. He received first prize in the contest, as well as a feather-shaped silver pen and a diploma.

José Rizal was an important figure in Filipino history and literature. His literary works such as the poem “Mi último adiós” and the novel Noli Me Tangere are classics of Filipino literature still studied in school. Read on to learn more!

Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo

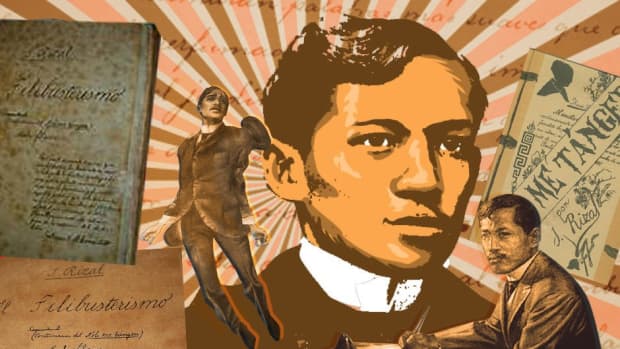

José Rizal is best known for his novels Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Subversive), which depict the effects of government corruption and abuse on individuals’ lives.

Based on Rizal’s own experiences and 19th-century novel conventions, Noli Me Tangere, published in 1887, depicted a protagonist, Crisostomo Ibarra, a young man who returned to the Philippines after studying in Europe. When he returns, he is brimming with ideas for bettering the home of his fellow citizens. However, corrupt church officials and cruel administrators thwart his idealistic plans.

El Filibusterismo is the sequel to Noli Me Tangere and Rizal’s second and final novel. Ibarra is disguised as Simoun, an immensely wealthy and mysterious jeweler who has gained the confidence of the colony’s governor-general (the main antagonist). Both novels are taught in schools as part of the general Filipino curriculum.

Left: Knights of Rizal Centennial Stamp (2016) / Right: Cover of Noli Me Tangere (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Noli_Me_Tangere.jpg)

“Goodbye to Leonor”

Like any other writer, Rizal’s works are artistic expressions of his emotions, experiences, and ideologies. Besides his famous revolutionary writings, Rizal also wrote melancholic and romantic pieces, such as his short poem “Goodbye to Leonor,” which he wrote for a woman he loved for many years but to whom he ultimately had to say goodbye.

Although simply written, an excerpt from this poem, “so it has come at last — the moment, the date, / when I must separate myself from you,” demonstrates the sincerity and depth of his feelings. This small masterpiece was out of the lonely, aching heart Leonor Rivera left him with.

Unfortunately, the two were never able to be together due to Rivera’s parents’ strong disapproval of Rizal as a suitor. They stayed in contact for many years through letters while Rivera was in Europe. However, Rivera eventually married an English railway engineer, whom her mother greatly favored over Rizal. This event devastated Rizal and resulted in “Goodbye to Leonor.”

Is José Rizal a Feminist?

In contrast to Rizal being a playboy, he was a feminist and a firm believer in women's empowerment. In his letter "To the Young Women of Malolos," he emphasized that women should be given equal opportunities as men. He also expressed his respect and appreciation for all Filipino women, including mothers, wives, and even single women.

Because women are often viewed as “fragile,” Rizal advised them not to allow themselves to be taken advantage of despite their lack of education. He wished to open his people’s eyes and help bring them out of ignorance.

“Mi último adiós”

“Mi último adiós” (“My Last Farewell”) was Rizal’s final poem written for his homeland and fellow citizens before his execution for sedition and rebellion. In this poem, he emphasized that what matters is not where one dies but why and for what reason. Furthermore, he underlined that all deaths are honorable if given for the sake of home and country.

Although Rizal died at the age of 35, his literary works outnumber that of many writers who lived a full life. He has published three novels (one of which is unfinished), four plays, 17 poems, three musical compositions, four speeches and petitions, nine historical commentaries, four letters and petitions, and 49 articles and essays. Completing these many varied works proves that Rizal lived a purposeful, full life.

Full Text of “Mi ultimo adiós”

Transl. by Charles Derbyshire (1911)

Farewell, dear Fatherland, clime of the sun caress'd

Pearl of the Orient seas, our Eden lost!,

Gladly now I go to give thee this faded life's best,

And were it brighter, fresher, or more blest

Still would I give it thee, nor count the cost.On the field of battle, 'mid the frenzy of fight,

Others have given their lives, without doubt or heed;

The place matters not-cypress or laurel or lily white,

Scaffold or open plain, combat or martyrdom's plight,

T is ever the same, to serve our home and country's need.I die just when I see the dawn break,

Through the gloom of night, to herald the day;

And if color is lacking my blood thou shalt take,

Pour'd out at need for thy dear sake

To dye with its crimson the waking ray.My dreams, when life first opened to me,

My dreams, when the hopes of youth beat high,

Were to see thy lov'd face, O gem of the Orient sea

From gloom and grief, from care and sorrow free;

No blush on thy brow, no tear in thine eye.Dream of my life, my living and burning desire,

All hail ! cries the soul that is now to take flight;

All hail ! And sweet it is for thee to expire ;

To die for thy sake, that thou mayst aspire;

And sleep in thy bosom eternity's long night.If over my grave some day thou seest grow,

In the grassy sod, a humble flower,

Draw it to thy lips and kiss my soul so,

While I may feel on my brow in the cold tomb below

The touch of thy tenderness, thy breath's warm power.Let the moon beam over me soft and serene,

Let the dawn shed over me its radiant flashes,

Let the wind with sad lament over me keen ;

And if on my cross a bird should be seen,

Let it trill there its hymn of peace to my ashes.Let the sun draw the vapors up to the sky,

And heavenward in purity bear my tardy protest

Let some kind soul o 'er my untimely fate sigh,

And in the still evening a prayer be lifted on high

From thee, O my country, that in God I may rest.Pray for all those that hapless have died,

For all who have suffered the unmeasur'd pain;

For our mothers that bitterly their woes have cried,

For widows and orphans, for captives by torture tried

And then for thyself that redemption thou mayst gain.And when the dark night wraps the graveyard around

With only the dead in their vigil to see

Break not my repose or the mystery profound

And perchance thou mayst hear a sad hymn resound

'T is I, O my country, raising a song unto thee.And even my grave is remembered no more

Unmark'd by never a cross nor a stone

Let the plow sweep through it, the spade turn it o'er

That my ashes may carpet earthly floor,

Before into nothingness at last they are blown.Then will oblivion bring to me no care

As over thy vales and plains I sweep;

Throbbing and cleansed in thy space and air

With color and light, with song and lament I fare,

Ever repeating the faith that I keep.My Fatherland ador'd, that sadness to my sorrow lends

Beloved Filipinas, hear now my last good-by!

I give thee all: parents and kindred and friends

For I go where no slave before the oppressor bends,

Where faith can never kill, and God reigns e'er on high!Farewell to you all, from my soul torn away,

Friends of my childhood in the home dispossessed!

Give thanks that I rest from the wearisome day!

Farewell to thee, too, sweet friend that lightened my way;

Beloved creatures all, farewell! In death there is rest!

“Ang kabataan ang pag-asa ng bayan”

Until today, our national hero’s works have remained in our lives, particularly among the youth. The youth—just as Rizal believed—can bring about social reform and improve societal conditions. Are they, however, truly the hope of the future when older generations doubt and belittle them?

Even if many dismiss the capabilities of the younger generation, we cannot brush aside their efforts, commitment, and burning spirit of volunteerism that they embody. We cannot deny that the youth are more involved in politics than ever. This demonstrates that Dr. Rizal’s famous words “Ang kabataan ang pag-asa ng bayan” remain relevant and alive even more than a century after his passing.

Further Reading

Hays, Jeff. “Jose Rizal’s Execution and Filipino Rebellions Against Spain.” Facts and Details, https://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Philippines/sub5_6a/entry-3839.html.

“José Rizal.” José Rizal University, http://bayaningrizal.pairserver.com/jru/.

Related Articles

- A Synopsis of Jose Rizal's Novel "El Filibusterismo"

This article is based on Jose Rizal's "El Filibusterismo." This novel is a sequel to "The Noli." It has a little humor, less idealism, and less romance than "The Noli Me Tangere." It is more revolutionary and more tragic than the first novel. - Dr. Jose Rizal's "The Social Cancer" and "Reign of Greed"

"Noli Me Tangere" and "El Filibisterismo" are two of Dr. Jose Rizal's many literary masterpieces that spoke about nationalism, patriotism, rights, justice, and freedom.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2022 Elisha Joy Gattoc