The 1964 Venice Biennale was a landmark in art history — was it rigged?

‘Taking Venice’ recreates the 1964 transport of Robert Rauschenberg’s work for exhibition at the 1964 Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

At the height of the Cold War, the U.S. government decided that one of the best ways to fight Communism was… with a stuffed goat.

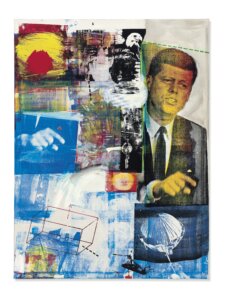

In 1964, the U.S. aimed to make a splash at the Venice Biennale, the world’s most prestigious art exhibition. Enter Alice Denney, a well-connected Washington art insider, who recommended Alan Solomon, an ambitious Jewish curator known for shaking things up. Solomon teamed up with Leo Castelli, a prominent Jewish art dealer from New York, to secure the Grand Prize for Robert Rauschenberg, an avant-garde artist who used car parts and comic strips in his work.

Rauschenberg’s art was an electrifying blend of painting, sculpture, found objects, and pop culture imagery. The American team’s audacious tactics drew sharp criticism from the international press and left Rauschenberg questioning the political motivations behind his selection.

Since its inception in 1895, the Venice Biennale has served as a stage where artistic reputations are forged and shattered. Dubbed the “Olympics of Art,” it has become a vital arena for nations to exhibit their cultural achievements. The 1964 Biennale, punctuated by Rauschenberg’s contentious victory, remains a pivotal moment in art history. As the 2024 Biennale commemorates the 60th anniversary of this landmark event, it offers a poignant reflection on its lasting impact on the art world.

Taking Venice, directed and co-produced by Amei Wallach, uncovers the true story behind the 1964 Venice Biennale scandal. The film delves into the rumors that the U.S. government and insiders rigged the competition to ensure Rauschenberg’s victory. Through archival footage and interviews with artists, curators and critics, Wallach’s documentary weaves a tale of suspense and political intrigue against glamorous parties and passionate debates about art.

I spoke about the film and its history with Wallach, an award-winning art critic, journalist, and curator, who has served as chief art critic for New York Newsday and an on-air arts commentator for The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.

Laurie Gwen Shapiro: More than a few people I know have always wrongly assumed Rauschenberg was Jewish.

Amei Wallach: Oh, I’ve got a great story several people told me, but I like how the art critic Irving Sandler told it best. You know Rauschenberg’s “Monogram,” right? (Rauschenberg’s “Monogram is his most famous “combine”—a blend of painting and sculpture—featuring a stuffed Angora goat encircled by a tire on a painted wooden platform.) Well, it was at that Jewish Museum’s 1963 retrospective of Rauschenberg that Alan Solomon overheard two trustees talking. All the garbage, goats, and all that stuff in the exhibition affronted them. One of them said, “Well, at least he’s a nice Jewish boy.” Solomon corrected them, saying, “He’s not Jewish.” The other trustee responded, “Well, thank God for that!”

So what was the reaction to “Monogram” in Venice?

Actually, although the tire-wearing goat was the star of the Jewish Museum retrospective, it never made it to Venice. The unmade bed and the stuffed eagle combine were the shockers there.

What drew you into this caper tale in the first place?

After my last film, I was talking to my producer about distribution, and we started brainstorming ideas for the next movie. She said, ‘Well, I was at the 1964 Venice Biennale…’ and it all came back to me — all these rumors and legends about the 1964 Venice Biennale. The more I studied this urban legend and learned about it, the better the story became. I began in earnest in 2016. Shortly after that, I went to an exhibit of photographs by Ugo Mulas, who had captured Rauschenberg’s paintings being loaded onto boats and ferried around Venice. Seeing those images, I thought, “I have a film.”

Alan Solomon was a great character in the film! When did he pass away?

I think he died in 1972. He was in his 40s when he died. His career was checkered after the Biennale, but he was a brilliant man and died very young.

One thing I learned from your film was that Castelli was Jewish. When did you find out that he was Jewish?

When Rob Storr (the critic and former dean of the Yale School of Art) told me in the film that he was Jewish, it was the first I heard.

You have a German or Jewish background, right?

I have a confused background because my parents were German Jews, and they felt they were more German than Jewish, as German Jews often did. They went to the synagogue on high holidays, and that was it. When they came here, my father was baptized, and he baptized me. I went to Sunday school and was raised a Christian. My mother became a Quaker.

Meanwhile, my mother’s sister, Dorothy, returned to Germany in the summer of 1945 in an American army uniform. My aunt, Dorothy Lewenz, was very adamantly Jewish, which I think was much healthier than what my parents did. She was asked to listen in on phone calls to determine if people were still Nazis or could be denazified. Because she was there, she had access to showers and food while the Germans weren’t getting any, which gave her a sort of revenge. She told me later she was thinking, “You wanted to destroy me but look at you now.”

When she returned to the U.S. when I was 11, she wanted her nephews and nieces to know they were Jewish.

At what point did you think, “I’ve got this legendary story,” and decide to dive into the archives? And where did you find your gold?

I started by reading books on the subject, which led me to some archives. I didn’t realize how archival this film would be until my producers said it would be 75% archival. We began with the Rauschenberg Foundation in New York, which has an extensive archive, much of it online. Then, I hired Madeline King, a talented young archivist, and Yanina Valdivieso, who has been invaluable in gathering materials. Between them, they collected a vast amount of archival material.

You were making this documentary during the pandemic, right? How did that rough ride affect the filmmaking process?

Yes. Fortunately, in the spring of 2019, three years in, I decided to go to Venice and recreate the boat heist, including scenes of Solomon finding an exhibit space and Rauschenberg skating in Saint Mark’s Square. Having that footage was crucial. During the pandemic, finding an editor was a challenge, but then we realized editing could be done over Zoom. I eventually found Rob Tinworth, a brilliant editor in Boston, and our composer was in Singapore. We made it work seamlessly across continents using Zoom, screen sharing, and various tech tools.

You’ve been immersed in the New York art world for ages — you knew Rauscheberg personally. Do you have any standout memories?

Of course. I met him through Tanya Grosman, who founded Universal Limited Art Editions in 1957. Grosman’s first artists were Larry Rivers, Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. I watched Rauschenberg make prints, including one memorable day with Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. I also visited Rauschenberg in Captiva, Florida, where he had several studios. He had an unconventional routine: sleeping until 4:00 PM, then joining dinner preparations with a glass of Jack Daniels. We’d eat at midnight and then go to his studio. He craved a community of friends and fellow artists. After one of his museum exhibitions, he hired a Staten Island Ferry for a night of drinking, dancing, and having a jolly time. It was an unforgettable experience.

I was always struck by his depth of humanity. I just didn’t know what a remarkable person he was. Instead of being exhilarated and high in Venice, he had all his silkscreens destroyed so he wouldn’t repeat himself. He’d arrived in Venice just before the Biennale opening creating stage sets, lighting and costumes, blending his visual art with dance as the set and costume designer on the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s world tour. He then continued on with the company to India and Japan. Significant events like Selma and Vietnam were going down in America, and he began creating art that responded to these powerful moments in history.

In the 80s, Rauschenberg faced ridicule for his ambitious Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) project. Announced in 1984 and named after his pet turtle, ROCI was born from his belief that art could be a force for positive change. Funded mainly by Rauschenberg, he traveled to countries where artistic expression was suppressed, aiming to spark dialogue and foster mutual understanding. Between 1985 and 1990, ROCI visited ten countries, culminating in a final exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 1991. While many dismissed it as a stunt, Rauschenberg’s effort was profoundly human and incredibly generous, embodying his conviction that art could communicate and create peace.

Well, we all know he was not Jewish — so what kind of family did he come from?

He came from an ultra-Christian evangelical family. It was very rigid, and he wasn’t supposed to dance. Growing up in that environment and being gay, he escaped as soon as he could. He loved to dance.

Do you think he had the love of his life?

His relationship with Jasper Johns was incredibly formative for both. It was a meaningful relationship for them as artists because they understood each other deeply. They could talk, move, and see things in mutually inspiring ways. Their relationship lasted from around 1958 until 1962. They became lovers, but it was hazardous to be gay at that time. There were laws against it in the state of New York. However, within their circle of artist friends, it was more acceptable. They had communities where they could be themselves, even if society wasn’t accepting. Both Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were very private about their relationship. They were open in their circles but didn’t publicly discuss it to respect each other’s privacy. By all accounts, when they became lovers, it was an electric connection. Only some people know Rauschenberg was married to painter Susan Weil from 1950 to 1953, and they had a son named Christopher before divorcing. Despite his later relationships, including with Johns, he didn’t hide his past but navigated his personal life with discretion due to the social climate. So, was Johns the love of his life? I don’t know because he had some pretty significant gay relationships after that.

Again, I was thinking much more than I expected after seeing your film about Alan Solomon, who saw the spark of greatness in an artist everyone thought was a stuntman. He had vision, didn’t he? As you dug into this story, did your respect for Solomon’s foresight grow even more?

Solomon totally got it. Leo Castelli understood the power of Pop Art and Rauschenberg and Johns as its precursors. He also introduced Johns’ work to artists like Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. But he thought Rauschenberg and Johns were leading the way. That was exciting and represented what was new in American art. He was a visionary. As for Rauschenberg, he said, “I was considered a clown,” but that’s not entirely true. There were people besides Solomon who understood what he was doing. He had a show at Whitechapel in January 1964. There were others back then who knew his worth. However, the backlash was pretty dramatic, especially from the Abstract Expressionists and the critics who supported them.

Rauschenberg seems to have lived quite an adventurous life. Can you share a particularly wild or unexpected story about him?

AW: One thing that hasn’t been highlighted enough since our festival debut is how adventurous and fearless Rauschenberg was in his personal life, not just in his art. For example, I asked Alice Denney, Do you think Rauschenberg wanted to win?’ She replied, “Like everything else in Bob’s life, sure, let’s win. Let’s go.”

Alice told me about how Jack Kennedy invited some women in the arts to advise him on which artists to invite to his inaugural, including Alice Denney started the Jefferson Place Gallery and was instrumental in bringing pop art to D.C., knew Rauschenberg well and suggested names like Mark Rothko and Ibram Lassaw for the inauguration. She told me a wild story that takes place during that presidential weekend where Bob decided, on a whim, to swim across the Potomac River one night. He was with Alice and her husband, George, and they went from pool to pool when Bob suddenly said, “I’m going to swim the Potomac.” Despite their protests, he insisted. Of course, he had been drinking, which made it even more dangerous. But that was Bob — constantly pushing boundaries and living with an audacious spirit. So they drove to the river, turned on the car headlights to illuminate the water, and he swam across the Key Bridge. The following day, he was very ill, and they realized just how close they came to losing him that night. He was always up for a challenge, no matter the risk. But we almost lost him that night.

Is there something you wish people had picked up on, something beyond the wild caper at the heart of the film? Something that’s been missed in the headlines and reviews?

For me, the film captures the extraordinary context of those times when the U.S. believed we were the saviors, riding in on the white horse to make things better. My documentary isn’t just about the art; it’s about the era, the influence of art, and how everything eventually unravels. We explore that unraveling in the film, too. Within a few months, you could see the chaos unfolding in the news.

We live in a very chaotic world again right now.

Absolutely. And what I hope people take away from Taking Venice is that art has always been a powerful lens through which we can understand our world. Art can spark dialogue, inspire change, and offer hope even in chaos.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.