The Blandification of Southern Rap

Local pride has fueled some of the best hip hop in history, but as one region's profile has risen over the past decade, its identity has been watered down.

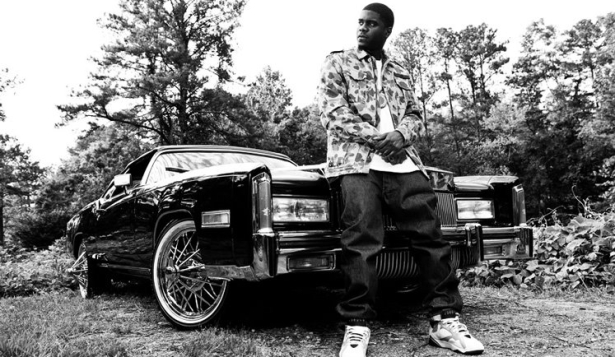

Rapper/producer Big K.R.I.T. is an immense talent from Meridian, Mississippi, a relatively unmarked swath of the hip-hop map. His distinguished mixtape career features music that offers a rare mix of introspection, soul samples, and twang-enhanced swagger. The reviews for his first commercial LP, Live From the Underground (out last week) have been strong, with Billboard calling it "a stirring triumph" and XXL praising "the cohesion of verses, songs and, in turn, the album." But while the acclaim is largely warranted—the topics K.R.I.T. tackles are certainly more diverse than those typically found on a major label rap album—to my ears, something is missing: a sense of place. Over and over, K.R.I.T. mentions his Mississippi roots and proclaims his love for the South, but the record, like so many ostensibly "Southern" rap records these days, feels like nowhere.

The first rappers came from places that were supposed to be silent and invisible. When the Cross Bronx Expressway slashed through New York City, residents who were displaced and disregarded got the message: Their communities and lives were worth less to the government than commuters who needed to expedite their trips to and from the suburbs. This pattern of urban "development" came alongside the depletion of industrial jobs in urban centers, the Reagan administration's slashing federal aid to cities nationwide, and a turn to mass incarceration as form of social control in American ghettos. From the mid-'70s through the '80s, representing one's neighborhood and city to the outside world through hip-hop was more than an expression of local pride: At its most powerful, it was an affirmation of humanity in the face of stereotypes and governmental neglect.

In what came to be known as "The Bridge" battle, KRS-1 and Boogie Down Productions produced "South Bronx," perhaps the classic example of local representation through rap. Prompted by a song from Marley Marl's Juice Crew about Queens, KRS recounts hip-hop's origins in the Bronx, where "power from the streetlight made the place dark," and yet pioneers like Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, and legions of forgotten DJs and b-boys created a vibrant party culture in the midst of poverty and violence. The music matches the mood of the lyrics, and the unapologetic boom-bap of the track meshes perfectly with KRS's New York straight talk.

The Juice Crew provided KRS-1 with competitive motivation, but the goals of representing extend beyond besting opponents. Describing home has become one of the key means to establish an identity. Ice Cube's anthem "It Was a Good Day" conjures an alluring yet ordinary non-Hollywood Los Angeles through Cube's matter-of-fact narration and a laid-back beat built from an Isley Brothers sample. Lesser-known jams, like Lauryn Hill's "Every Ghetto, Every City" and Common's "Reminding Me (Of Sef)," describe growing up in New Jersey and Chicago with local references unfamiliar to most listeners. But the cumulative impact of these earnest, sometimes obscure descriptions is a profound sense of each artist's native habitat.

Provincialism occasionally morphs into intense rap competition with higher stakes than "The Bridge" battle. In a few cases, musical turf wars have mixed with the more dangerous toxins of masculinity and impoverished ghetto life, and violence has ensued. In the '90s, personal clashes were amplified by record companies and media outlets into regional beefs with tragic consequences, and the deaths of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. still serve as cautionary tales about blurring the lines between art and life.

MORE ON MUSIC

Despite these tragedies, putting it down for one's hometown remains resonant, in part due to New York hip-hop's historical centrality and elitism. Throughout the late 20th century, when rap acts from outside New York made it big, they validated not only artists' individual talents, but their city or state's stature as a place worthy of hip-hop respect. The commercial success of groups from Los Angeles forced national recognition of the diversity and richness of hip-hop in California and the Pacific Northwest. In addition to West Coast hip-hop, the 1990s brought national attention to "third coast" cities like Houston (Scarface and the Geto Boys), Atlanta (Outkast), Miami (2 Live Crew), and New Orleans (Master P's No Limit Records and Cash Money Records).

New York hip-hop style, including sparse, grimy beats and rough and rugged rhymes, continued to set the standard for what was considered "real" rap into the early 2000s. Soon, though, New York began to face real challengers to its claim on the center of the hip-hop universe. Today, anyone who denies the spectacular regional variation in quality American hip-hop is living in the past. And perhaps the most surprising development in hip-hop's evolution is the triumph of "the South" as hip-hop hegemon. The influence of giants like Scarface and Outkast is complemented by the overdue respect now paid to Southern veterans like UGK, 8ball, and MJG, and the recent commercial viability of Lil Wayne, T.I., Young Jeezy, Rick Ross, and others.

However, the seeds of the South's undoing are starting to bloom. An oversized bed of regional pride is fertile ground for malignant growth, as weeds of "Southern" celebration choke out the smaller, fantastically unique, and local vegetation that nourished hip-hop for the past decade. As books by Roni Sarig and Ben Westhoff point out, what makes Southern rap so significant is not the idea of "the South." It's the local flavor of innovations like New Orleans bounce, Miami bass, and Houston's chopped-and-screwed sound. Even within specific southern cities, hip-hop cultures are widely divergent. Chopped-and-screwed music is just one shred of Houston hip-hop, and Atlanta is perhaps the prime example of Southern diversity: Outkast's evolution from Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik to ATLiens and beyond is entirely different from Lil Jon's commitment to crunk and Gucci Mane's leisurely swag and trap music.

The more the South is celebrated as a monolith, though, the more meaningless it becomes. When "Southern" rather than local identity becomes primary, rappers forget themselves and churn out records that sound like they could have been written by a Northern city-slicker. "The South" becomes synonymous with hackneyed forms of consumption, and "country folk" are identified by their love of soul food and Cadillacs rather than their multifaceted musical imagination.

K.R.I.T.'s Live from the Underground, for instance, begins with a two-minute intro that sounds ripped from an Outkast album, as K.R.I.T. offers a spoken word performance about perseverance and keeping the faith over a space-age beat. The two songs that then follow, "Live From the Underground" and "Cool 2 B Southern," are purposeful attempts to establish K.R.I.T.'s origins. But the hook from each describes a scene that seems to exist in every Southern rap album that hits iTunes. On "Live From the Underground" K.R.I.T. raps:

Pushin rhymes underground like moonshine

With jump like juke joints

Ridin' like old 'lacs [Cadillacs]

Down like four flats

Shine like gold grills

Curls and chrome rims

Bitch you know what it is

I'm live from the Underground

And "Cool 2 Be Southern" echoes:

I'm talkin' 'bout the dirty South, folks with he grills in mouth (We make it cool to be Southern)

Everybody wanna ball nowadays, but don't nobody wanna get paid (We make it cool to be Southern)

Get down if you wanna, crackin seals' blowin' some marijuana (We make it cool to be Southern)

Return of forever all day, them country people feel what I say (We make it cool to be southern)"

Perhaps listeners (like me) who are frustrated with this definition of "Southern" culture just don't know what it's like to be "country." But Nelly (St. Louis), Lil Jon (Atlanta), and Ol' Dirty Bastard (New York) took gold and diamond studded teeth to the mainstream years ago, and Dre and Snoop (Los Angeles) were smoking and low-riding on chrome rims in the early 1990s. There must be more to "the South" than dental work, candy-painted cars, and no-frills liquor, because if not, the South includes the West Coast, Midwest, and Northeast.

What's more, the weight of Southern rap history slows Underground down. To be sure, the South's regional hip-hop narrative cannot be understood without reference to its musical pioneers, and paying respect to one's elders and muses is valuable. But with K.R.I.T.'s album and others, the references are both overdone and overbroad. In addition to the Outkast-inflected intro, Live From the Underground includes a sex-themed collaboration with Ludacris, whose first mega-hit was driven by the hook "I wanna lick-lick-lick-lick you from your head to your toes." A penchant for lyrically limber freakiness remains one of Luda's most pronounced traits, but not one of K.R.I.T.'s.

In another case of déjà vu, the chorus to K.R.I.T.s "Money on the Floor" sounds like an extended version of Lil Scrappy's "Money in the Bank" (2006), as both songs employ a chopped-and-screwed vocal sample as the centerpiece of the hook. "Money on the Floor" also includes verses from the suddenly ubiquitous 2 Chainz, who hails from Atlanta, and Memphis legends 8ball and MJG. So a sampling technique founded in Houston is the backbone for a record with two 40-year-old rappers from Memphis, another guest with a gaggle of charted collaborations, and K.R.I.T., who is far and away the best lyricist of the bunch but leaves little imprint on the music. Major record labels' insistence on packing rap albums with collaborations is not Southern rappers' fault. But in the case of Underground, these partnerships detract from the more impressive and intimate tracks, like "Rich Dad, Poor Dad," that make K.R.I.T. who he is.

As author Murray Forman once put it, the 'hood often comes first in hip-hop, and representing is here to stay. But some forms of representation carry more weight than others. The South is no longer the aggrieved underdog; it is king of the hill. Its climb was a beautiful and disjointed process, as piece by piece, cities and rappers with their own ideals of southern authenticity scraped and clawed their way upward. Now, at the summit, stagnation has set in, and the track where rappers tell us about their low-riders and wild nights at the strip club is stuck on repeat. For the South to continue to thrive, each rapper who claims it has to go back home.