Ramsey Lewis can tell you the precise moment he knew it was time to quit the road. “I was about 80, 81, and the limo pulled up in front of O’Hare [Airport] and the skycap asked us what gate we were going to,” recalls the pianist, now 86. “And my wife said, ‘Whatever you do, do you mind getting my husband a wheelchair?”

Lewis pauses over the phone. “I used it; I wasn’t mad,” he continues, “but as the wheels got rolling, I said to myself, ‘OK, buddy, maybe it’s time to start thinking about ending this grind.’”

It was not a simple thing to do. “I had so many [performance] commitments that it took me about three years to exhaust them,” he says. After that, the lifelong Chicago resident put trips to O’Hare and Midway Airport behind him, as well as concerts in front of audiences.

These days, Ramsey Lewis refers to himself as “retired.” But that’s a relative term. He still plays the piano a couple of hours a day — and not just for enjoyment. He begins his sessions by playing scales and arpeggios and other exercises. Yes, he practices. “A lot of players neglect their left hand and I don’t want mine to fall asleep,” he says. After warming up, Lewis might play Bach, Beethoven or Chopin in lieu of jazz.

One day in 2020, shortly after the Coronavirus pandemic abruptly shut down the world, Lewis was at his piano trying to work out a song from memory, a Russ Freeman ballad titled “The Wind.” It took him about an hour, and he finally nailed the tune. Lewis was not aware that his wife, Jan, had surreptitiously recorded his final version on her iPhone.

They sent the file to Lewis’s manager, Brett Steele, who birthed an idea: The Ramsey Lewis Saturday Salon series, which kicked off in April of last year, is a live stream that shows Lewis playing solo for an hour on a six-foot Steinway from his spacious, well-appointed living room in the hip Streeterville section of Chicago. It happens on the last Saturday of each month.

During the pandemic, musicians of all ilk turned to streaming when their live gigs dried up. They wanted to play. They hoped that viewers would drop a little something in the digital tip jar. The results were mixed, and largely dismal for jazz musicians. Lewis was among the few exceptions. He charged $20 for access and, Steele says, his biggest audience was 1,500. That’s $30K — for an hour — with no overhead, other than the purchase of some special microphones and video recorder. (It’s a static, single-camera shoot.)

Lewis says he gives most of the revenue to the Jazz Foundation of America, which has an emergency fund for struggling musicians. “I won’t say I don’t need the money … but I don’t need the money,” he says playfully. “When you’ve been as blessed as I have, you’ve got to share it. You can’t put your chest out.”

The success of the Saturday Salon is a testament to Lewis’s ongoing commercial viability in a musical idiom, jazz, not known for it. It takes some thought to name other jazz players who’ve enjoyed the level, and the longevity, of commercial success that Lewis had. (Armstrong, Miles and Herbie come to mind.)

The pianist’s mainstream popularity began in 1965 with the Ramsey Lewis Trio’s out-of-the-blue, No. 5 pop hit “The ‘In’ Crowd” — and it never waned. “Many of my albums sold very well,” Lewis says matter-of-factly (six achieved Gold status). Perhaps more important, he was handsomely paid for performances.

Lewis has released more than 80 albums — with much of the music highly produced, soaked in strings and background choirs, and later, synthesizers and shiny horn sections, some of it intended to capitalize on current trends (Country Meets the Blues, Bossa Nova from the early ’60s), some of it squarely in the pop-jazz realm.

His most influential work came early on, when his acoustic trio infused its sound with the gospel influences and rolling, Ray Charles-style grooves that were such a part of the pianist’s early life. Lewis had a knack for adapting the day’s pop hits into a soul-jazz format and, at least early on, making it sound authentic. He was more inclined to record songs like “Moondance,” “Uptight,” “Hang on Sloopy,” “Dancing in the Street” and a raft of Beatles tunes than another round of Tin Pan Alley chestnuts. This approach has not endeared Lewis to critics and has tended to obscure the notion that he has always been a serious and dedicated pianist. If the jazz community was resentful of his wealth and the music that generated it, he’s not aware. “None of the guys I’d work festivals with would give me the cold shoulder,” he recalls. “And I mean the hard-playing jazz guys. We’d laugh and they’d tease me. What’d they used to call me? Pocket Money, I think.”

His most influential work came early on, when his acoustic trio infused its sound with the gospel influences and rolling, Ray Charles-style grooves that were such a part of the pianist’s early life. Lewis had a knack for adapting the day’s pop hits into a soul-jazz format and, at least early on, making it sound authentic. He was more inclined to record songs like “Moondance,” “Uptight,” “Hang on Sloopy,” “Dancing in the Street” and a raft of Beatles tunes than another round of Tin Pan Alley chestnuts. This approach has not endeared Lewis to critics and has tended to obscure the notion that he has always been a serious and dedicated pianist. If the jazz community was resentful of his wealth and the music that generated it, he’s not aware. “None of the guys I’d work festivals with would give me the cold shoulder,” he recalls. “And I mean the hard-playing jazz guys. We’d laugh and they’d tease me. What’d they used to call me? Pocket Money, I think.”

As for how he feels about the critical derision, that never came up in our two-hour interview. The only time Lewis bristled (slightly) was when I mentioned his 1968 album Mother Nature’s Son, which I referred to as a collection of Beatles covers. Lewis cut me off. “We never say someone’s covering a Duke Ellington song, or a Gerswhin song,” he says. “So when I hear someone say that I’m covering Beatles songs, it’s like I’m doing it for the money. I play songs that I dearly love, and that includes Lennon/McCartney songs. They’re fun to solo on.”

“When we started playing ‘The In Crowd,’ people started clapping, hollering, some got up and were dancing. The three of us looked at each other like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Ramsey Lewis grew up in a close-knit, church-going family in a working-class Black neighborhood on the north side of Chicago. He pleaded to take piano lessons around age 7 because his older sister did. “At first, my folks said no ‘because we can’t afford the 50 cents,’” Lewis remembers. “I kicked the floor enough that they finally said, ‘OK, you can go.’’

The pianist had dual music educations. His father, Ramsey Lewis, Sr., directed the church choir, and young Ramsey was entranced by how his singing could rouse the people in the pews. Soon he started playing piano in the church band. He also attended Chicago Musical College and studied classical piano with a petite woman named Dorothy Mendelsohn. Lewis recalls fondly, “She hammered into me, ‘you must make the piano sing,’ and to ‘listen with your inner ear.’”

Lewis played gospel with a guy a few years his senior, Wallace Burton, who also led a popular jazz/R&B band in town called The Clefs. He invited Lewis to join. Lewis’s parents, concerned that playing jazz might harm his classical technique, arranged a meeting with Mendelsohn. Lewis recounts, “I was still in my teens at this point and she says to my folks, ‘Can I be honest with you? There’s room for one, maybe two, African-Americans in classical music, and as good as Ramsey is, he won’t be able to make a living. If he has an opportunity to earn some dollars playing jazz, give him a chance and see what he can do.’”

Lewis signed on with The Clefs. Problem was, he didn’t know how to play jazz. At the first rehearsal, Lewis recalls, “Wallace said, ‘give me an intro to a B-Flat blues. “I said I don’t know the blues.’ He said, ‘OK, let’s play ‘How High the Moon.’ I said, ‘I don’t know How High the Moon.’ He said, ‘Go sit over there,’ and he took me home to my parents.”

Burton didn’t give up on his new bandmate, though. He taught Lewis some basics and directed him to study jazz pianists. Lewis remembers sitting for hours in listening booths at record stores and absorbing Erroll Garner, George Shearing, Bud Powell, Red Garland and others. He also loved Art Tatum — who “scared me” — and R&B stars, especially Ray Charles.

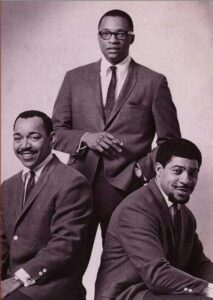

It wasn’t long before Lewis, bassist Eldee Young and drummer Redd Holt split off and formed the Ramsey Lewis Trio. During an engagement as the house band at a nice restaurant, they caught the attention of influential Windy City disc jockey Holmes “Daddy-O” Daylie. He brokered an audition with Chess Records, which had spun off the Argo label for jazz releases. The group signed and put out its debut, Ramsey Lewis and his Gentle-men of Swing, in 1956.

The trio gigged steadily, and in nine years released 20 albums on Argo, as many as three a year, generating modest sales. Then came a moment that would dramatically alter Lewis’s life. “We’d been out on the road for two or three months, and were playing at the Minor Key in Detroit when I got a call from Phil Chess,” he says. “He said, ‘I think you guys’ got a hit.’ I said, ‘What?!’ Jazz musicians never talked about hits.”

The success of the “The ‘In’ Crowd” single drove the album of the same name to No. 2 on the Billboard 200. The Beatles’ Help! held the top spot. “I looked at [the chart] for 45 minutes,” Lewis says, “right up there under The Beatles.”

To hear Lewis tell it, “The ‘In’ Crowd” almost didn’t happen: “We were playing mostly standards at the [Bohemian Caverns] nightclub in D.C. and we were ready to play the theme and take it on out. It was Redd who said, ‘Why don’t we play the new song?’ I said ‘Oh, right.’ Up to that point the crowd had given us the usual polite applause, our propers,” Lewis says. “When we started playing ‘The In Crowd,’ people started clapping, hollering, some got up and were dancing. The three of us looked at each other like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Fifty-six years later, the aural evidence remains. As soon as the insistent 4/4 gospel groove kicks in, the audience perks up, and the enthusiasm builds throughout the performance.

Lewis’s lifestyle changed virtually overnight. The pianist says that he and his family moved into a nicer neighborhood, his kids went to better schools, and he moved up from driving a Plymouth to a Cadillac Fleetwood. The band’s performance fees spiked. Lewis went on a spending spree. “I was buying anything I wanted, didn’t even look at the price tag,” Lewis says, bemused. “After about a year, my first wife, who passed, said, ‘We can’t keep going through money like this.’ Fortunately, I listened.”

Lewis was living the high life while jazz was enduring a downward spiral in popularity. Most music historians — and musicians, for that matter — cite the mid-‘60s rise of The Beatles and rock ’n’ roll’s subsequent grip on the youth audience as the primary reason for jazz being relegated to cult status. While Lewis lends some credence to that theory, he thinks another factor was more important.

“Jazz had become very common in the average household, and what happened?” he muses. “John Coltrane came along and, God bless him, became [highly influential], sold some records, and so many musicians thought, ‘This is the way,’ and went in the direction of Coltrane. But they were not John Coltrane. Jazz began to lose popularity as that went on. Musicians lost sight of the music reaching the average person. The average guy, and his wife, they come home from working all day, they don’t want to be educated. They want to be entertained.”

Lewis never strayed from making what he calls “reach-out-and-touch music.” And he got paid for it. Lewis remained on Chess subsidiaries until 1974, when he switched to Columbia. Chess, whose main vein was releasing records by blues legends Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter — as well as Chuck Berry — had a reputation of skimping on royalties, as did many of the period’s white-owned labels who specialized in Black music. Lewis doesn’t think he got shorted.

“Fortunately, Daddy-O Daylie was our manager and on occasion he would go down to see Leonard and Phil Chess with us,” Lewis says. “He’d look over the royalty statements and say, ‘I think the fella sold more records than this.’ [Chess] needed him and his radio show. They’d say, ‘Let us go back and take a look.’ They’d come back and say, ‘Sure enough, you did sell more. Here’s another check.’ One time, [Chess] gave my wife a mink coat. Daddy-O said, ‘Great, she’s going to enjoy it, but that by no means takes the place of royalty statements that reflect actual sales.”

Lewis scored one more significant pop hit, this time under his own name, after the Trio had disbanded. In 1966, “Wade in the Water,” a funky version of an old slave song, reached No. 19 on the singles chart. From 1965 to 1984, Lewis placed 28 albums on the Billboard 200. His performance fees remained substantial throughout his long musical tenure. He says he did not experience any career dry spells. “I was never calling my agent looking for work,” he says. “In fact, it was the opposite. I would be looking for a couple of weeks off.”

Lewis scored one more significant pop hit, this time under his own name, after the Trio had disbanded. In 1966, “Wade in the Water,” a funky version of an old slave song, reached No. 19 on the singles chart. From 1965 to 1984, Lewis placed 28 albums on the Billboard 200. His performance fees remained substantial throughout his long musical tenure. He says he did not experience any career dry spells. “I was never calling my agent looking for work,” he says. “In fact, it was the opposite. I would be looking for a couple of weeks off.”

That’s no longer a problem for the prolific octegenarian. Lewis is not the sort of man to sit around considering his legacy. “The only time I reflect on things is when I do interviews with guys like you,” he says. “I live in the moment — today, maybe tomorrow, but I don’t get too much into next week and next month. I’m working on my chops, getting ready for my next Saturday afternoon show.”

Lewis’ next show will take place June 26. Tickerts are $20. To purchase, click here. For tickets to additional shows, click here.