It Was Overlooked In The '90s, But 'Nightbreed' Is Clive Barker's Masterpiece

The Plot Is Practically Biblical

Photo: 20th Century Fox"I always think the whole thing about the 'lost tribe' is Biblical anyway," Barker said about the plot of Nightbreed, "as is the idea of a lost tribe being found and led to safety or salvation - or attempting to but failing as in this particular case..."

Those familiar with Barker's other works will probably not be surprised to find religious imagery being employed in the narrative - after all, Barker's bibliography includes books with titles like Sacrament and Galilee. "There's a kind of religious subtext, an iconographic thing going on," Barker said of all of his work.

In Nightbreed, the Biblical touches go beyond subtext. The name of Midian is, itself, drawn from the Bible, which we see in a scene where the drunken priest Ashberry quotes scripture about clashing with Midian. At one point, Lylesburg, the leader of the 'Breed, is called Moses, and the 'Breed's broken god Baphomet is referred to as the Baptizer. Perhaps the most strikingly Biblical element of the film is the main plot of Boone, who rises after perishing, inadvertently brings disaster down on Midian, and ultimately delivers the surviving 'Breed from their oppressors.

It's The Mos Eisley Cantina Scene Of Horror Movies

Photo: 20th Century FoxIn making Nightbreed, Barker wanted to create something that was just jammed to the absolute rafters with different monsters - what he called "a ride through the space between my ears, a trip through Clive Barker's skull."

"Nightbreed is a hymn to variegation," Barker said in the film's press kit. "No 'Breed looks like any other 'Breed. In the same way the cantina sequence in Star Wars worked the first time you saw it, I want audiences to have the impression that there is this great gathering of creatures and they are never quite sure they've seen them all."

To that end, Image Animation created a bevy of creature designs (many of them adapted from Barker's own sketches) using all kinds of practical effects, from makeup and prosthetics to stop-motion animation. The 'Breed are littered throughout the movie, and not saved until the end. In one of the film's most striking sequences, Lori descends through the depths of Midian and sees many of its monstrous inhabitants for the first time by peering into chambers that are set up like individual theatrical productions or rooms in a Halloween haunted house.

Within these thresholds, as Barker explains, are "creatures that are monstrous and beautiful in the same moment, which has always been my favourite condition for any creature."

It Depicts Humans As The Real Monsters

Photo: 20th Century FoxBarker has said repeatedly that his intent with Nightbreed was to create a film that asks the audience to "cheer the monsters." Most stories and movies that do this achieve their ends by bowdlerizing their monsters, but not Barker. The 'Breed are sympathetic, certainly, but not at the expense of what makes them monstrous. They're still scary, dangerous, and powerful, but they're also humane, and ultimately just people, with their own fears and hopes, dreams and desires.

Humanity, on the other hand, as "represented by priest, cops and analysts - the three forces of authority - are absolutely, unreservedly b*stards," Barker says. The monstrousness of the human characters is hypocrisy. They wear false faces (literally, in Decker's case) and revel in their cruelty, all the while feeling justified in their hatred of those who are different from them.

At the beginning of the film, we see a mural that shows the history of the persecution of the 'Breed by humanity, and later two of the 'Breed show Lori just a glimpse of that persecution. They tell her that the Nightbreed left in Midian are the only remnants of the once-plentiful Tribes of the Moon. "You call us 'monsters,'" one of the 'Breed says, "but when you dream, you dream of flying, and changing, and living without death. You envy us, and what you envy..."

"We destroy," Lori finishes for her. It's a line of dialogue that could have easily been uttered by Barker himself, who says, of the Nightbreed, "I enjoy the monsters and I want them to be as life-affirming as any human beings."

It's Got Monsters From Hell To Breakfast

Photo: 20th Century FoxMost entire movie franchises don't manage to cram in as many different monsters as Nightbreed does. There's a porcupine woman, a guy who has weird eel-like things that come out of his stomach, a moon-faced guy, a girl who turns into a strange little dog puppet when sunlight hits her, and a woman with fingers on her chin. Basically, if you can imagine it (and even if you can't), chances are you'll see it somewhere in Nightbreed. And that's all before they let the Berserkers out.

"Mad b*stards," as one character calls them, the Berserkers are the members of the 'Breed who are too monstrous, too uncontrollable to be let loose into the general population - which, once you see the general population, you realize must be quite something. In practice, they look sort of like Swamp Thing as a football player, but there's a whole pile of them and, of course, they get loose during the film's epic final conflict.

The Nightbreed Worship A Giant, Sentient Baphomet Statue

Photo: 20th Century FoxAt the bottom of Midian is the chamber of Baphomet the Baptizer, who made Midian. Played in the film by Bernard Henry, Baphomet is represented by a huge, partially incomplete, glowing statue in the center of an enormous, shrine-like room.

In an interview with Horrorfan magazine in 1989, Barker talked about his ideas for Nightbreed's version of Baphomet:

The Knights Templar brought back from the Holy Land a god called Baphomet and they were burned at the stake for worship of him. The Rosicrucians also had Baphomet in their system, as did the Masons. He's a very ambiguous god - no one really knows where he came from. Some say it was the severed head of John the Baptist that talked brought back by the Knights, others suggested it was some kind of Islamic god.

It Features One Of Danny Elfman's Best Scores

Photo: 20th Century FoxWell known for composing the scores to more than 100 movies, including Men in Black, the Sam Raimi Spider-Man films, and pretty much everything Tim Burton has ever worked on, not to mention the theme of The Simpsons, Danny Elfman has a lot of movie soundtracks under his belt - but Nightbreed has to be one of his best. The choral-backed score, which Clive Barker called "the most uncompromised portion of [the] entire movie," helps to sell the film's mythic scope.

The soundtrck also features a strange, slow, almost country-and-western version of the 1990 song "Skin" by Elfman's band Oingo Boingo. "Skin" was the third single released from Oingo Boingo's second-to-last studio album, which came out in February 1990, just like Nightbreed.

The Sets Are Grandiose And Bizarre

Photo: 20th Century FoxThe necropolis of Midian, "where the monsters live," is brought to life through a combination of elaborate sets and matte paintings. The sets for the surface are incredible enough - with enormous, overgrown crypts and mausoleums decorated with gargoyles jutting up above the heads of the characters as they explore - but once we go underground, Midian is even more impressive. The underground city where the 'Breed make their home is a maze of Pueblo-like rooms connected by swinging wooden bridges that span an enormous central chamber.

The contents of these rooms vary from simple monastic cells to baroque decor filled with eels in fishbowls, giant cages in which strange beings feast, and other wonders. The walls are painted with stylized murals showing the history of the 'Breed. At the bottom of the city is the chamber of Baphomet the Baptizer, which is filled with columns and statues and burning light.

The 'Breed aren't the only ones who enjoy striking set design, either. In contrast to the baroque variegation of Midian, Dr. Decker's office is all sparse whites and modernist design. When we see him alone, in what looks like a conference room, the table set with dozens of knives, his surroundings are even more striking. A grisly black-and-white image is repeated on the wall behind him, between two back-lit bubble walls.

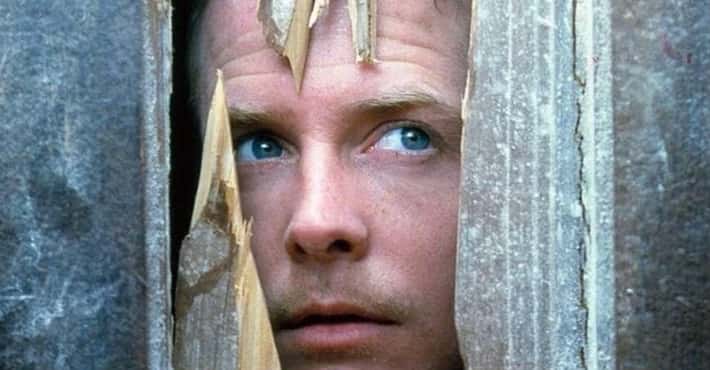

Filmmaker David Cronenberg Plays A Sinister Psychologist

Photo: 20th Century FoxIn a bit of inspired casting, legendary body horror director David Cronenberg plays Dr. Decker, the psychologist who begins the picture working with Craig Sheffer's Aaron Boone. Of course, Dr. Decker has a little secret of his own - he's actually the slasher whose misdeeds he's trying to pin on Boone. As Ol' Button Eyes, Cronenberg's Decker offers up a memorable villain while also serving as the human antagonist of a film filled to bursting with monsters.

"For me it couldn't be more perfect casting," Clive Barker said of Cronenberg in an interview with Horrorfan magazine that was conducted during filming. "I don't think I'd realized how good he actually looks until I saw him on film. He looks very chilling. He offers up these wide, sympathetic grins, then they suddenly vanish off his face..."

It Features A 'Special Appearance' By John Agar

Photo: 20th Century FoxAt one point in the movie, Dr. Decker torments an old man in a filling station to acquire information about Midian and the 'Breed. When Decker asks the old man why he knows so much about them, he replies that he had wanted to be one of them, to join them. "Did they kick you out?" he asks Decker then, "Is that why you hate 'em so much?" Decker's target is played by John Agar, who is given a "Special Appearance" designation in the film's credits.

Agar achieved genre fame by playing square-jawed heroes in '50s monster movies like Revenge of the Creature, Tarantula, The Mole People, Brain from Planet Arous, and others. In other words, Agar always played exactly the kinds of people who hunt the 'Breed down, dig them up, and end them. Putting him in the film as someone who longs to join them gives the scene an extra layer of pathos and irony.

Horror Authors Like Neil Gaiman Make Cameo Appearances

Photo: 20th Century FoxBefore he was a filmmaker, Clive Barker was a horror author, and he doesn't forget his roots. John Skipp and Craig Spector were two authors who rose to prominence in the '80s as leading figures in a horror movement that was called "splatterpunk" - a genre to which Barker himself was often relegated. They also make cameo appearances in Nightbreed. Along with Peter Atkins, the screenwriter of several of the Hellraiser sequels, they were originally going to play 'Breed whose characters ultimately got removed from the main story of the movie, though they still show up briefly.

They aren't the only authors to make cameo appearances, either. In a club scene in Barker's restored director's cut, we can see none other than Neil Gaiman in a cowboy hat. At the time, Gaiman had only started writing his Sandman comics. Barker, a fan, wrote the introduction to the comic's second volume, The Doll's House, just two months after Nightbreed's release.

Several Actors From The 'Hellraiser' Series Join The Cast

Photo: 20th Century FoxDoug Bradley, who had played Pinhead in Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser 2 just a few years before, plays Lylesburg, the leader of the Nightbreed, who has scars on his cheeks that hide a strange secret. He's not the only Barker alum to show up in Nightbreed, either. Oliver Parker, who plays Peloquin, one of the most prominently featured of the 'Breed and the one who gives Boone "the bite that mocks death," had cameo appearances as a moving man in both Hellraiser and Hellraiser 2. The moon-faced Kinski is played by Nicholas Vince, who was the "Chatterer Cenobite" in those same films.

Simon Bamford, who was under the latex of the "Butterball Cenobite" in the first two Hellraiser films, plays the tattooed Ohnaka in Nightbreed, and Catherine Chevalier, who briefly appeared in Hellraiser 2, plays Rachel, the member of the 'Breed who can transform into mist. Even David Young, who plays the conjoined Otis & Clay in Nightbreed, had a cameo as a bouncer in Hellraiser 3 just a couple of years later.

Now There's A Director's Cut That's Closer To How It Was Meant To Be Seen

Photo: 20th Century FoxPart of the reason Nightbreed never got its due in the '90s was because the version released to theaters and home video was "compromised" - to use Barker's word - by studio meddling. According to the writer/director, the theatrical version of Nightbreed was "frankly screwed up by the studio who wanted me to take certain sequences out and simplify it in a way that frustrated me." The studio wanted something closer to a "slasher film," and demanded various changes, including a different fate for the film's villain, Dr. Decker.

"We tested this movie," Barker recalled at the Fangoria Weekend of Horrors in Los Angeles in 1991. "[W]e tested it twice with [the original] ending and the audience said, 'Sorry, don't like that ending,' and Twentieth Century Fox said, 'OK, get rid of it.'"

For years, the theatrical version of Nightbreed was the only one that was available, but recently, some of the original footage was dug out of storage. Clive Barker then sat down with producer Mark Millar and others to create a definitive "director's cut" of the movie, which removes several scenes from the original version and adds in almost 40 minutes of restored footage - amounting to more than 80 changes from the original, including more monsters. Scream Factory, known for their deluxe edition Blu Rays of cult films, released this new cut of Nightbreed in 2014.

While fans may quibble over whether this new version is the "definitive" one, since footage from the theatrical version was removed and replaced, it is certainly much closer to Barker's original vision for the film.

It's Been Called Barker's Most Queer Film

Photo: 20th Century FoxClive Barker is an openly gay horror creator, yet his films don't always manage to contain as much queer text or subtext as his fiction sometimes does. As such, in spite of the heterosexual love story at the heart of the film, Nightbreed has often been seen as Barker's most openly queer film - with the 'Breed acting as an obvious stand-in for LGBTQ individuals, or any other marginalized group you can imagine.

Director Alejandro Jodorowsky called it "the first truly gay horror fantasy epic," and readings of Nightbreed as queer cinema have ranged from the superficial to the in-depth. Many such interpretations revolve around the idea of finding a family and an accepting home among those whom society has deemed Other, while others focus on the way Decker seems to project himself onto Boone.