Pictures of Death

When photography was new, it was often used to preserve corpses via their images. An Object Lesson.

Photography owes much of its early flourishing to death. Not in images depicting the aftermath of violent crimes or industrial accidents. Instead, through quiet pictures used to comfort grieving friends and relatives. These postmortem photographs, as they are known, were popular from the mid-19th through the early-20th centuries—common enough to grace mantelpieces. Many can be viewed anew at online resources like the Thanatos Archive.

Historians estimate that during the 1840s, the medium’s first decade, as cholera swept through Britain and America, photographers recorded deaths and marriages by a ratio of three to one. Budding practitioners had barely learned to handle the bulky machinery and explosive chemicals before they were asked to take likenesses of the dead: to bend lifeless limbs into natural poses and mask tell-tale signs of sickness, racing against rigor mortis.

Many people find photos of the dead creepy or morbid. No question, postmortem photographs are sorrowful images. They capture the ravages of illness. They depict grieving parents. They show wives caressing the faces of lost husbands, just for a chance to be tender toward them one last time. And they portray unbearably beautiful children, poised as if asleep, surrounded by the toys they played with while alive. But today, the sorrow of these images lies elsewhere: in treating pictures of the dead like obscenities rather than as memento mori.

* * *

Photography extended the centuries-old traditions of death masks and mortuary paintings, which commemorate the dead by fixing them in an illusion of life. But compared to these earlier media, photographs possessed an almost magical verisimilitude. “It is not merely the likeness which is precious,” wrote Elizabeth Barrett Browning of a postmortem portrait, “but the association and the sense of nearness involved in the thing ... the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever!” For many, procuring a postmortem photo must have felt like a funerary ritual—a way of allowing the dead to become fully dead. But this new invention also had something of resurrection about it. It animated a body, astonishing viewers each time they gazed upon it.

During the 1840s and early 1850s, a postmortem photo would likely have been the first and only portrait of someone. At $2 each (roughly $60 today), photographs were costly, and in America’s open expanses, studios were miles away from most households. But death changes things. People who had never given a thought to the medium now turned to it in desperation. Decades later, in trade journals like The Philadelphia Photographer, veteran practitioners wrote of how parents would arrive at their doorsteps with stillborn infants, to whom they hadn’t even given a name. “Can you photograph this?” implored one young mother, opening a wooden basket to reveal “a tiny face like waxwork.”

Almost all the postmortem photographs from this period are daguerreotypes. The dominant mode of photography for its first 15 years, the daguerreotype was rendered on a copper sheet burnished to look like a mirror. When held at the right angle, a grieving widow would have seen her image meld with that of her husband, a striking reunion after death. Daguerreotypes were produced as three-dimensional objects, meant for the hand as much as the eye. They came in small cases of leather or ebony, opened by a delicate handle. Inside, the image lay cuddled in velvet. Like tiny reliquaries, daguerreotypes kept safe the image of one’s beloved. They kept other things, too, like a baby’s silken curl or a piece of a girl’s ribbon.

Many postmortem pictures show parents cradling their children, or wives alongside their deceased husbands. The corpse figures prominently, but so do the shattered expressions of those left behind. A surprising number of fathers appear—at this time, men could openly admit their grief. There are parents so young they look like children themselves. Many subjects make trembling attempts at self-composure.

Rituals help the living overcome the desire to die with the dead. As a ritual, postmortem photography helped check grief. By pressing subjects to execute specific poses and gestures, death photos helped the living externalize personal loss. The faces of many mourners evidence the struggle. How else to interpret a daguerreotype of a mother lying next to her child?

Many photographs from the 1840s and ’50s depict a corpse posed in a semblance of sleep. The convention makes death look easy and gentle—a rest from labor. “It has a heavenly calm in it,” the English author Mary Russell Mitford remarked of her father’s cast in 1842. But this conceit has an ulterior motive: to trick the viewer into believing that death is sleep, no metaphor about it. Consider the image above, of a boy who bears no trace of decay in his luscious round face. And yet for every photo like this one, a dozen more exist in which photography’s irrepressible realism exposes the charade, in the form of fever sores or sunken eyes. Such images mix comfort with a kind of cruelty.

Postmortem daguerreotypes are piercingly intimate. They bring the viewer close enough to the face of the dead to see a boy’s long lashes, or a girl’s spray of freckles. Many were taken at home. No props here: These are the chairs the dead once sat in, the toys their living bodies held. It is in these daguerreotypes especially that we discover what the French critic Roland Barthes called the “punctum” of a photograph: the accidental element that “wounds” a viewer with its poignancy. In a daguerreotype labeled “Our Darling,” for example, the humble detail of the girl’s dirty fingernails reveals the truth of every postmortem photograph: the life that the dead left behind.

* * *

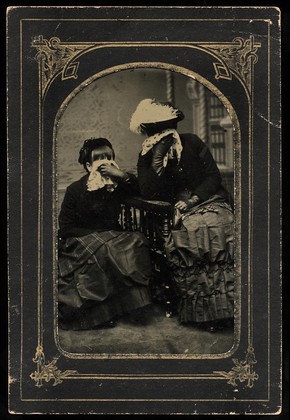

Beginning in 1851, daguerreotypy gave way to the wet collodion process, which made photography cheaper, faster, and reproducible. The medium soared in popularity, and the market for postmortem photography expanded. As it did, the aspirations for postmortem photos also rose. By the 1860s, death photos began explicit attempts to animate the corpse. Dead bodies sit in chairs, posed in the act of playing or reading. In one striking tintype dated 1859, a young boy perches on a seat, eyes open, holding a rattle. A close look reveals a wrinkle on the left side of the backdrop: a clue that someone, most likely the photographer’s assistant, is propping the child up. In a cabinet card from the 1890s, a young girl holds a plaything in one hand and a doll in the other. Parents and photographers engage in a nostalgic game of make-believe. But the dead children refuse to play along, looking more inanimate, somehow, than their toys.

This slide into sentimentality, even if grotesque, coincides with a profound shift in Western attitudes toward death. The 1870s witnessed the advent of a religious upheaval in America and Western Europe. Traditional arguments about immortality lacked the weight they carried only a few decades earlier, especially among the middle and upper classes. Accounts of death during this period no longer expressed the piety and spiritual fervor of earlier times.

No wonder, then, that the effort to tame and beautify death in daguerreotypes collapsed in the late 19th century. In its place, a confusion of approaches appeared. Some postmortem photos still portrayed peaceful, domestic images of the dead. But the faces in those images are mostly Latin American, Eastern European, and working class. It was a sign, perhaps, that these groups possessed a deeper faith in God—or in photography.

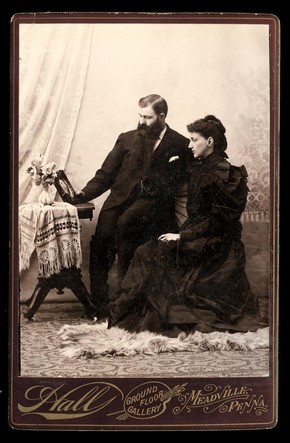

Meanwhile, members of the white middle-class began to procure photos of themselves in mourning, no corpse in sight. Many of these subjects are women, attired in black crepe. They weep into handkerchiefs, or turn their backs to the camera. The photograph’s earlier stoicism gives way to the performance of grief, as if melodrama were supplanting faith. Other mourning photographs foreground the act of remembrance. Bereaved ones stand or sit next to portraits of the dead, recalling the anthropologist Nigel Clark’s comment that in an age of disbelief, death has nowhere to go but memory.

Beginning in the 1890s, postmortem photography turned toward burial. No pretense at life here: just death, flat and absolute, marked by coffins and cemeteries and a community that carries on. Reproduced on postcards, these images traveled to distant friends and relatives. They became vulnerable to the postman’s stamp and other desecrations. The postmortem photograph had devolved from a near-sacred object to a formality, a social obligation. By the mid-1920s, it disappeared from public view, defeated by Kodak and its happy promotion of snapshot photography. Underneath photography’s new lively glee, however, the fear of death quietly smoldered. Photographic reminders of it began to be judged as obscene.

Every so often, postmortem photography experiences a brief resurgence. The organization Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep, for example, recruits volunteer photographers to take images of stillborn or dead infants for grieving parents. And a few years ago, it was a trend among teenagers and 20-somethings to take selfies at funerals. “Caskies,” they coined them. These trends hardly became mainstream, earning more reproach than approval.

* * *

The dead help the living face what lies ahead. In exchange, the living must translate the lives of the dead into history. They can find myriad ways to do so, from visiting gravesites to writing someone’s biography. But photography has become so commonplace that images of death have lost most of their original meaning.

Many postmortem photographs are hard to look at. They’re too graphic or too desperate in their attempts to simulate life. But others provide an almost visceral connection to the past. Visiting the Thanatos Archive, I linger over the faces of the bereaved, remembering what it feels like to lose someone you love. I learn the names of the dead before me: Odie, Sulisse, Viola. I discover the strange ways people die (brain fever, an accidental swallowing of coyote poison) and the all-too-familiar ways they do (cancer, an accidental gunshot). And I surrender to my own fears of dying. I see, as if in palimpsest, my demise in these portraits of strangers, and I recognize that mortality connects us all.

This post appears courtesy of Object Lessons.