What happened to Edward and his younger brother Richard?

The disappearance of the 'Princes in the Tower', Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York in 1483 is one of the most intriguing 'murders' of the Tower of London. The mysterious episode unfolded with sinister speed over a single summer, yet is still being debated by historians centuries later.

The Princes, sons of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, were born during the intense turmoil of the Wars of the Roses. On Edward’s death in 1483, his brother the Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) became Lord Protector of Edward’s son and heir, the 12-year-old Edward V. The Duke immediately placed Edward in the Tower of London, closely followed by his 9-year-old brother Richard, for 'their protection’.

What became of these young boys remains a mystery: they were never seen alive again. We may never know the truth about the poor princes, but they were victims of one of the most vicious inter-family conflicts this country has ever known.

Header image: The Princes in the Tower (detail), after Paul Delaroche (1797-1856). © Historic Royal Palaces

Did you know?

In 1674, the bones of two children of similar ages were found beneath the staircase in the White Tower at the Tower of London.

The Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455-85) were a series of civil wars, with two rival branches of the Plantagenet family fighting over the throne of England. The House of Lancaster was led by the then King Henry VI (symbolised by the red rose) and his cousin Edward IV headed the House of York (white rose).

Both men were direct descendants of Edward III and there had already been previous disputes in the family for the control of the throne.

In 1461 Edward IV managed to imprison Henry VI in the Tower of London and take his crown. This first period of Edward IV’s reign was marked by violence and the new king was usually away, fighting to defend his throne.

Image: Edward IV (1442-83), c1524-56 by the British School. This is one of the five earliest paintings surviving in the Royal Collection. RCIN 403435, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Edward IV's secret marriage

Sometime during the spring or summer of 1464 (historians disagree on the exact date), Yorkist Edward IV married the widowed Elizabeth Woodville.

The marriage, announced in September, was not well received at court; Edward must have anticipated the negative reaction, for they married in secret in Elizabeth's family chapel. Only her mother Jacquetta, Countess of Rivers knew of the event.

Image: Former chronicles of England by Jean de Wavrin, depicting the secret marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, © Bibliothéque nationale de France

An unpopular choice

Although Elizabeth was called ‘the most beautiful woman in the Island of Britain,’ she was not considered a suitable match for a king. She came from a respected, genteel family, but one that lacked titles or diplomatic allies. Even worse, the Woodvilles were Lancastrian supporters. So was Elizabeth's late husband, Sir John Grey of Grosby, who died in the battlefield fighting for the House of Lancaster.

At the time of their marriage, Edward’s cousin Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick was planning for the King to marry a French princess. The alliance would strengthen the support for the House of York. Warwick, one of the most powerful men in the kingdom, was so enraged by Edward and Elizabeth’s union that he switched to the Lancastrian side.

Did you know?

Edward had his brother, Duke of Clarence, executed for treason at the Tower. Some say he was drowned in a butt of malmsey wine.

Family favours

As soon as Elizabeth became queen, her family was showered with favours, to the court’s further annoyance.

Her two sons from the first marriage and her many siblings either married into the nobility or gained prime positions at court.

It also helped Edward for his wife's family to grow in influence. Loyal relatives provided additional support to the King against Warwick’s powerful circle.

Despite the court’s disapproval, it seems Edward and Elizabeth had a successful relationship. During the 19 years together, they had ten children (seven daughters and three sons).

Five of the daughters - Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Catherine and Bridget – reached adulthood, and except for Bridget (who became a nun), all married well. Elder daughter Elizabeth of York eventually married Henry VII.

Image: Elizabeth Woodville (1437?-1492) c1550-1600, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018, RCIN 406785

Readeption of Henry VI

In 1470 Henry VI’s Lancastrian supporters freed him from the Tower and had him re-crowned. The event was known as the ‘Readeption’.

Edward IV fled to Flanders with his close brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester (future Richard III). His wife, Elizabeth Woodville and their children sought refuge in St Peter’s Sanctuary within Westminster Abbey.

On 1 October 1470 the pregnant Elizabeth arrived at the Abbey, accompanied by her mother and three daughters, Elizabeth, Mary and Cecily. A month later, she gave birth to a son, Edward, who became the heir to the throne. The family lived in relative comfort under the Abbot’s care.

Did you know?

St Peter’s Sanctuary in Westminster Abbey was a chartered sanctuary, able to provide asylum to persecuted Christians, whether criminals or political figures.

Suspicious death of Henry VI

The Lancastrian Henry VI’s reign was cut short when Edward returned from exile in early 1471. He defeated Henry’s followers at the Battle of Tewkesbury, where Henry’s teenage son and heir was killed in the fighting. Henry was once again incarcerated in the Tower.

Then in May news came of Henry’s death. It was first thought he died of melancholy, but gradually suspicions arose that he was murdered by agents of the Duke of Gloucester while at prayer in the Wakefield Tower, a claim still unproven to this day.

However, his death effectively ended the Lancastrian line which was certainly convenient for Edward IV. Now he could strengthen his rule, having both an heir in his eldest son Edward, and a ‘spare’ in his next son Richard.

A king in the making

Under the King’s specifications, the young Edward was to have a balanced education, with enough time to play and to enjoy his dogs and horses. He was also to eat and sleep well and his household was to be free of ‘swearers, brawlers, backbiters, common hazarders, adulterers, words of ribaldry’.

While the Prince of Wales was in Ludlow, his younger brother Richard stayed with his mother and sisters. He was born in Shrewsbury in 1473 and was made Duke of York a year later. At the age of about 4 he was contracted to marry the 5-year-old Anne de Mowbray and became Duke of Norfolk in 1477.

Did you know?

Since Prince Richard's birth in 1473, it became tradition for the monarch’s second son to be titled Duke of York.

Death of Edward IV

On the 9 April 1483, Edward IV died unexpectedly, aged 41, possibly of pneumonia or typhoid.

By that time, he had achieved relative peace and prosperity, leaving behind a secured crown and personal fortune.

On his deathbed, the King entrusted his loyal brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as the Lord Protector to his heir.

Prince Edward was at Ludlow Castle when the news arrived of his father’s death. At the age of 12, he was now the new king and his brother Richard, aged 9, became heir presumptive.

Immediately, Edward V made his way to London, escorted by his maternal uncle, Earl Rivers.

Duke of Gloucester takes charge

Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was in the north of England, did not hear of his brother’s death immediately. Elizabeth and her family had decided to wait to send the news, as they wanted to be sure of their position within the new reign.

When the news finally arrived a few days later, Richard rushed to meet his nephew on his return journey and escort him personally. On 29 April, Richard intercepted the royal entourage. After dining with them, the following morning the Duke, despite Edward’s protests, had Earl Rivers and Elizabeth’s son Lord Richard Grey arrested and sent north. They were subsequently executed. On reaching London, Gloucester had Edward placed in the Tower of London ‘for his protection’.

Edward’s death had left his widow vulnerable. She was unpopular at court, and with Richard as Protector, she had lost control over the King. Her fears grew as many members of her family and close supporters were executed.

Image: Edward V by an unknown artist, 1597-1618, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Sanctuary at Westminster Abbey

Elizabeth was taking no chances, and once again she gathered up her children and servants and headed for sanctuary at Westminster Abbey.

She and her household arrived in April 1483. They brought so many possessions with them that her servants had to break down a section of the Abbey walls to get everything inside.

Image: Cheyneygates Room at Westminster Abbey as it looks today, where once Elizabeth Woodville and her family sheltered from their enemies. © Dean and Chapter of Westminster

The family is split

As long as Elizabeth Woodville and her children were together in sanctuary, they were relatively safe. Elizabeth also knew it was crucial to keep her son Richard, the heir presumptive, under her close guard.

This all changed when the Protector ordered that the young Prince join his brother at the Tower. Although she resisted at first, Elizabeth finally bid farewell to young Richard, never to see him again.

Did you know?

Legend has it that Elizabeth took part of the royal treasury with her into sanctuary and divided it between members of her family.

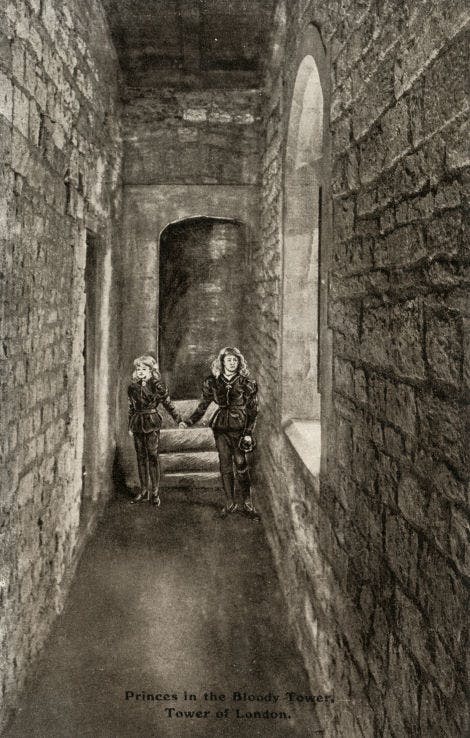

Edward V and Richard, Duke of York reunited

Initially, putting Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York in the Tower did not raise suspicions.

The two boys were very young and vulnerable – their safety was paramount.

The Tower was also the starting point for the coronation procession and it was traditional for a new monarch to stay there until the ceremony.

Image: The Meeting of Edward V (1470-1483) and his Brother Richard, Duke of York (1473-1483) contemplated by King Richard III. This romantically imagined scene by 19th-century artist James Northcote depicts the brothers younger than they were, heightening the sense of pathos. © National Trust Images / Derrick E. Witty

Imprisoned at the Tower

Edward’s coronation was scheduled for 22 June 1483 and preparations, such as minting coins, were underway.

However, over the following months, the celebrations planned for young King Edward V became a coronation for his uncle and Protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

In mid-June, Parliament declared the princes illegitimate on the grounds that their father Edward IV had contracted to marry Lady Eleanor Butler before he married Elizabeth Woodville.

This would have made his marriage to Elizabeth invalid.

With the princes’ claim to the throne discredited, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, became next in line as his other brothers, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and George, Duke of Clarence, had both died before Edward IV.

On 6 July the princes’ uncle was crowned King Richard III.

Having proclaimed himself King, Richard soon amassed enemies at court, and he grew more fearful of being usurped.

The last reference to the young princes is in the Great Chronicle, which on 16 June records that ‘the children of King Edward’ were ‘seen shooting [arrows] and playing in the garden of the Tower sundry times.’

A dark secret

According to the Italian chronicler Dominic Mancini, soon afterwards they were:

‘Withdrawn to the inner apartments of the Tower proper, and day by day began to be seen more rarely behind the bars and windows until at length they ceased to appear altogether. Already there is a suspicion that they have been done away with.’

Mancini was a minor diplomat at Edward IV’s court between 1482 and 1483.

As customary to foreign diplomats, he wrote a report of what he witnessed and heard (including gossip and rumours) of the life at court.

Mancini's account on the princes suggests that they were moved from the Garden or ‘Bloody’ Tower to the White Tower, where royal captives tended to be held.

Image: The Princes in the Tower, early 20th century postcard illustrating the interior of the Bloody Tower with two boys holding hands. © Historic Royal Palaces

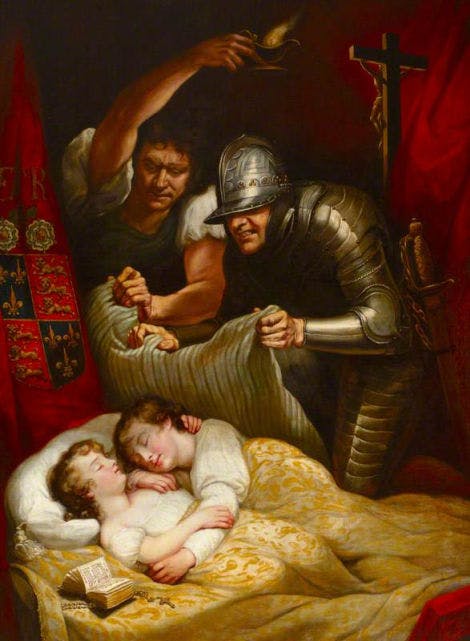

Were the 'Princes in the Tower' murdered?

What happened next has been the subject of intense debate ever since, and is one of the darkest chapters in the Tower’s long history. It is now widely believed that sometime during the autumn of that year, the two princes were quietly murdered. At whose hands, we will probably never know.

With Richard III now in control, it’s unlikely that anyone would dare raise the issue. After the princes disappeared, Elizabeth Woodville and her remaining children came out of sanctuary at Westminster and appeared to reconcile with Richard III, although this is hardly surprising given her vulnerable position. Gossip and rumours circulated at court about the fate of the boys, but no direct accusations were made against Richard.

Did you know?

The Princes’ mother Elizabeth later retired to a convent in London. On her death, she was laid, at her request, in a humble grave next to her husband Edward in St George’s Chapel, Windsor.

History rewritten

Around 30 years lapsed before the first account of the princes' disappearance was written. This was in an unfinished biography, The History of Richard III written by Henry VIII's Chancellor Sir Thomas More between 1513 and 1518. Not only was More writing some time after the event, but he was writing to validate a Tudor version of history. In this account, Richard is portrayed as the villain, blamed for ordering the boys' murders, to be carried out by two servants.

‘The innocent children lying in their beds, Miles Forest and John Dighton, about midnight, came into the chamber and suddenly lapped them up among the clothes, so bewrapped them and entangled them, keeping down by force the feather-bed and pillows hard unto their mouths, that within a while smothered and stifled, they gave up to God their innocent souls.'

Entire conversations between individuals are presented verbatim, despite More being a child himself when the princes disappeared in 1483.

Image: The Murder of the Princes in the Tower, a scene imagined by 19th-century artist James Northcote © National Trust Images

Fact or fiction?

More’s account describes Richard III’s physical appearance, mentioning his ‘ill features’, ‘small stature’ and ‘croaked [sic] back’ – a reference to a curvature of Richard's spine.

In More’s telling of the story, Richard's physical appearance is an outward expression of an evil and villainous mind.

This description of Richard later provided the inspiration for William Shakespeare’s play, 'Richard III'.

Image: Sir Thomas More after Hans Holbein the Younger, early 17th-century, based on a work of 1527. © National Portrait Gallery, London

The suspects

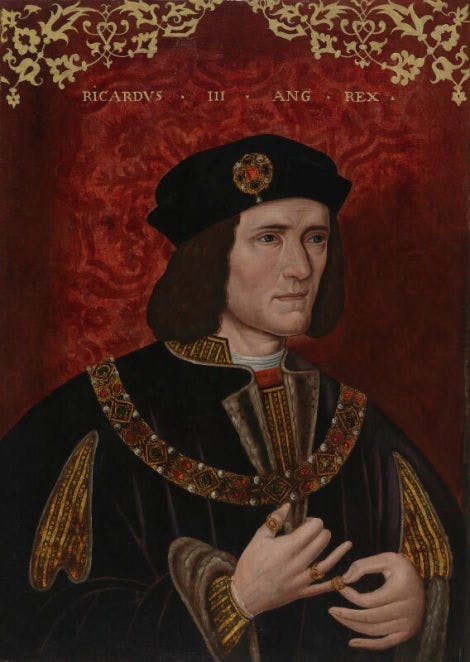

Richard III

The prime suspect has long been Richard III. He had invalidated his nephews’ claim to the throne and had himself crowned king.

His increasing paranoia as his enemies multiplied led him to having a close ally, Lord Hastings, arrested and executed at the Tower. While they lived, the young princes would have been an increasing threat to Richard.

But there were others who wanted the princes out of the way, too.

Image: Richard III, British School, 16th Century, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, RCIN 403436

Henry Stafford

Henry Stafford, the 2nd Duke of Buckingham was Richard’s right-hand man. There are theories that he took it upon himself to murder the boys to gain King Richard’s favour.

He later fell out with Richard and was executed for treason.

Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, probably by Jacobus Houbraken, after Hans Holbein the Younger, published 1747.

Image: © National Portrait Gallery, London

Henry VII

Following his seizure of the throne from Richard III in 1485, Henry VII executed rival claimants to the throne and then married the Princes’ elder sister, Elizabeth of York.

Her right to inherit was dependent on both her brothers being dead.

Image: Henry VII (1457-1509), c1550-1699, Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, RCIN 404743,

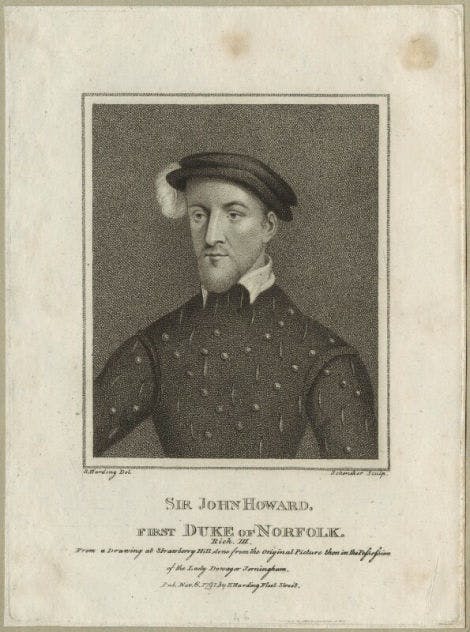

John Howard

John Howard was a loyal friend to Richard III. He had custody of the Tower at the time the princes disappeared.

He later gained young Richard, Duke of York’s Norfolk estate and title.

Image: John Howard, Duke of Norfolk by Schenecker, published by Edward Harding in 1791, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Margaret Beaufort

Margaret was mother of the future Henry VII, and paternal grandmother to Henry VIII. This highly intelligent, manipulative Lancastrian matriarch would have done anything to ensure that her son Henry was the next heir to the throne, including infiltrating the court of her Yorkist enemies.

Did this include getting the young Princes out of the way? She had a superb spy network and men loyal to her, who could have done the deed at her command.

Image: This portrait is a later version of the only known likeness of Lady Margaret Beaufort. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Imposters?

The case was made even more intriguing when, in 1491, a man called Perkin Warbeck claimed to be Richard, Duke of York. He said he had escaped from the Tower and spent the intervening years on the run. Over the next six years Warbeck travelled across Europe, convincing a number of important people, including Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and James IV of Scotland, to be ‘Richard IV of England.’ He also convinced Margaret of York, the aunt of the real prince.

In 1497, Warbeck attempted to invade England. He failed and ended up in the Tower of London. He confessed to being an impostor, and was later executed.

Did you know?

Warbeck claimed that Edward had been murdered in the Tower, but that he had been spared because of his age and ‘innocence’.

The end of the Wars of the Roses

The reign of Richard III only lasted for a couple of years.

On 22 August 1485, Richard was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field.

His opponent, Henry Tudor was crowned Henry VII on 30 October and in January 1486, married Elizabeth of York, the Princes’ eldest sister.

Henry was a Lancastrian descendant and together with Elizabeth, ended the Wars of the Roses and started the Tudor dynasty.

William Shakespeare

The mystery of the princes in the Tower, and the possible deaths associated with their story, became the inspiration behind Shakespeare’s Richard III. In this historical play, Richard is portrayed as the murderous villain.

He is responsible for stabbing the deposed Henry VI in the Wakefield Tower (while, according to Shakespeare, the devout King prayed); ordering the execution of his brother George, Duke of Clarence in a butt of malmsey wine; and ordering the murder of his two nephews, Edward V and Richard.

While this version would have excited theatregoers, it’s important to remember that Shakespeare was writing to please Elizabeth I, grand-daughter of Richard’s nemesis, Henry Tudor.

Skeletons in the Tower

Nearly 200 years later, in 1674, King Charles II ordered the demolition of what remained of the royal palace to the south of the White Tower. The location included a turret that had once contained a privy staircase leading into St John’s Chapel.

Beneath the foundations of the staircase, some 3m (10ft) below the ground, the workmen were astonished to find a wooden chest containing two skeletons. It was concluded that they were the bones of children.

Did you know?

An eyewitness described ‘pieces of rag and velvet’ adhering to the bones. Only royals could wear velvet.

Modern forensics

Following the discovery of Richard III’s remains in 2012, more sophisticated forensic tests were able to identify the bones as definitely those of the king himself.

This cast doubts were cast on the accuracy of the forensic examination carried out on the children’s skeletons back in 1933. For example, tests were not conducted into the gender of the bodies. Were they even boys?

Did you know?

Richard III’s skeleton showed no evidence of the limp or withered arm described by Shakespeare, although he did suffer from severe curvature of the spine.

Who did the bones belong to?

Also, in 1933 it was claimed that the children’s skulls showed evidence of a congenital condition causing missing teeth, inherited from their paternal grandmother Cecily, Duchess of York. However, Dr John Ashdown-Hill, a member of the Looking For Richard project, pointed out that Richard’s skull didn’t have this genetic anomaly.

‘This newly-revealed dental evidence is another remarkable discovery from the results of the Looking For Richard Project. Modern scientific analysis applied to the flawed 1933 investigation of the "bones in the urn" has revealed that the sex and historical period of death of the remains is unknown.’

Dr Ashdown-Hill also suggests that there may be more than two sets of bones present.

Image: Lower jaw with molar, thought to be the remains of Richard, Duke of York, one of the Princes in the Tower. © Dean and Chapter of Westminster

Will we ever know?

Someone, long dead themselves, knew what happened to the little princes.

Science may finally provide a way to identify the bones, but amid all the theorising, we shouldn’t forget that these were young children, trapped and terrified.

They became inconvenient pawns in a political game, and they were betrayed by adults they trusted.

Who those adults were we will probably never know.

Image: Detail of John Everett Millais, The Princes in the Tower, 1878, © Royal Holloway, University of London

Watch the Princes in the Tower: Murdered or Survived?

The boys disappeared from the Tower in the autumn of 1483. Speculation over their fate remains to this day and many questions remain unanswered.

Murdered or survived? What do you think?

Video Transcript of the Princes in the Tower: Murdered or Survived?

Follow along with an interactive transcript of The Princes in the Tower: Murdered or Survived? on YouTube. A link to open the transcript can be found in the description.

The Princes in the Tower by an unknown artist

Unknown artist after an original painting by Hippolyte-Paul Delaroche, c.1831-99

A copy by an unknown artist of a much larger painting (Paris, Louvre) first exhibited by Delaroche at the Paris Salon of 1831. The Princes are seen in their chambers at the Tower of London.

View this painting in high definition in this Gigapixel image, created in partnership with Google Arts & Culture.

History and myth at the Tower of London

Discover some of the Tower of London's greatest events and myths with our interactive story, created in partnership with Google Arts & Culture.

BROWSE MORE HISTORY AND STORIES

Lady Jane Grey

Known as the ‘Nine Day Queen’, Lady Jane had the shortest reign in British history

The Tower at war

The Tower of London played an important role in the First and Second World Wars

Tower of London remembers

The First World War centenary commemorations

EXPLORE WHAT'S ON

- For members

- Events

Members-Only Ceremony of the Keys

Members-only access to the traditional locking up of the Tower of London, the Ceremony of the Keys.

- 16 June, 14 July, 18 August and 08 September 2024

- 21:30

- Tower of London

- Separate ticket (advance booking required)

- Tours and talks

Audio Guide Tour

Explore deeper with the Tower of London audio guide tour. Discover extra information about the Tower's history, plan your day and find out more about our cafés and shops.

- Available

- Tower of London

- Separate ticket

- Things to see

Gun salute

See special commemorative firings at the Tower of London on the Gun Park located on the Wharf.

- Selected dates

- Tower of London

- Free

Shop online

Shop Raven gifts

Legend has it that if the six ravens ever leave the Tower of London, the Tower and the kingdom will fall. These products have been inspired by the Ravens that live at the Tower of London.

From £3.00

Medieval knights tankard

Medieval knights tankard inspired by the royal arms of England. Featuring intricate dragon detailing this beautifully designed mug has a detailed chain entwined around the handle. Perfect for re-enactments or a gift for someone who loves all things medieval.

£30.00

Tower of London White Tower luxury embroidered hanging decoration

Our exclusive premium decoration of the White Tower, the centre of the Tower of London. Built on the orders of William the Conqueror, the White Tower has now stood for almost 1000 years.

£30.00