- India

- International

The rebel has left the building:The legacy of Nabarun Bhattacharya

Bhattacharya, who won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1997 for Herbert, occupies an uneasy place in the pantheon of Bengali greats.

Nabarun Bhattacharya in a still from Q’s film that is not complete yet

Nabarun Bhattacharya in a still from Q’s film that is not complete yet

In Nabarun Bhattacharya’s celebrated novel Herbert (1993), the protagonist flirts with death throughout his life. His bedside has two books — All About the Afterworld written by Mrinalkanti Ghosh Bhaktibhushan and The Mysteries of the Afterworld by Kalibar Bedantabagish. As a clairvoyant who can communicate with the dead, he is a local celebrity. But then, Herbert is not alone in his preoccupation with death. Through him and many of other colourful characters, Bhattacharya talks about the different facets of death. At times, it’s a metaphor for decay, as is evident when he talks about the city “trundling to Nimtala (the biggest crematorium in Kolkata), cellphone held in a tight grip”. At times, he sees it as a form of liberation. But that’s where the similarity ends between them, for Bhattacharya was not Herbert. If anything, Bhattacharya was the antithesis of his most celebrated fictional creation. The 66-year-old was one of Bengal’s most subversive voices, radical in his politics, forever anti-establishment and outspoken in his views. “Nabarunda is not Herbert. He is one of the most respected writers of our times, unlike his fictional creation Herbert who is little more than a local sensation,” says Arunava Sinha, who translated Herbert as Harbert in English.

Bhattacharya, who won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1997 for Herbert, occupies an uneasy place in the pantheon of Bengali greats. The writer detested the Bengali trait of deifying authors and poets. His works challenged the genteel core of his readers, leading them through the city’s underbelly, speaking to them in a language that mocked their middle-class sensibilities and comfort in the status quo. His characters — termites, gnats, cockroaches, talking crows and flying humans called Fyatarus — who create mayhem to deflect evil machinations and political schemings, mingled effortlessly over their human counterparts. “It was difficult not to be swept into his world. Even his poetry was deeply entrenched in the word of occult. Readers found his prose seductive and sharp, yet he was relentlessly political. It’s difficult to resist such a combination,” says Bengali poet and writer Mandakranta Sen.

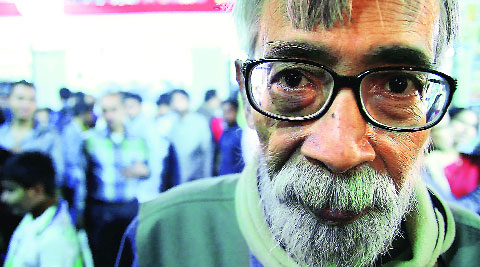

A still from the movie Herbert, an adaption of his novel by the same name (Courtesy: Suman Mukhopadhyay

A still from the movie Herbert, an adaption of his novel by the same name (Courtesy: Suman Mukhopadhyay

When filmmaker and theatre director Suman Mukhopadhyay met him for the first time in the mid-1990s, he was struck by how mild Bhattacharya was as a person. “I had just read Herbert and had expected him to be a different person. More sharp-tongued maybe, like his writing,” says Mukhopadhyay, who has made three films based on Bhattacharya’s works — Herbert (2005), Mahanagar@Kolkata (2009) and Kangal Malsat (2013). Like Bhattacharya, Mukhopadhyay earned the wrath of the ruling government for adapting Bhattacharya’s works for the big screen. In 2005, an adaptation of Herbert was refused a screening by the then Left Front government at the state-owned Nandan theatre, while last year his adaptation of Kangal Malsat was refused a certificate by the local revising committee of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) for its portrayal of contemporary Bengal politics. “He was used to such things. He tirelessly raised his voice against the establishment. These were minor issues for him,” says Mukhopadhyay.

Bhattacharya’s son Tathagata, a journalist based in Delhi, mentions how his father found it distasteful to fraternise with any political party. “Though he felt writers should be intensely political beings, he was against attending shows on news channels and events organised by political parties. He felt a writer’s work is to write,” says Tathagata. He was also disillusioned with the contemporary literary scene of Bengal. “Baba felt the writers are stuck in a rut. They haven’t opened their minds to new things. My father was a voracious reader, you could talk to him about the current political scenario in Ukraine as well as the ancient gardening technique of the Egyptians,” says Tathagata.

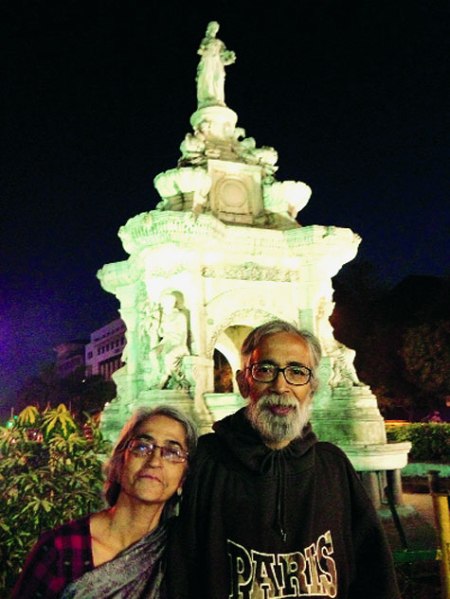

Nabarun Bhattacharya with his wife (Source: Tathagat Bhattacharya)

Nabarun Bhattacharya with his wife (Source: Tathagat Bhattacharya)

Filmmaker Q was impressed by Bhattacharya at their first meeting itself. “I had read Nabarunda’s works right after college. I don’t think that was the right time to read his work because I couldn’t fully grasp its depth. However, I came back to him later in life and realised how he has seeped into the deepest recesses of my mind,” says Q. When Q met Bhattacharya for the first time about two years ago, he had already been diagnosed with cancer. “I went to meet him as a fan and then decided to make a film on him. I wish we had more footage of him when he was healthy. My priority was to document his life and career,” says Q.

An unfinished novel and countless ideas is what Bhattacharya has left behinf, a fact that his son Tathagata rues. “He was also writing the last instalment of the story for our magazine Bhashabandhan,” says Tathagata.

May 22: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05