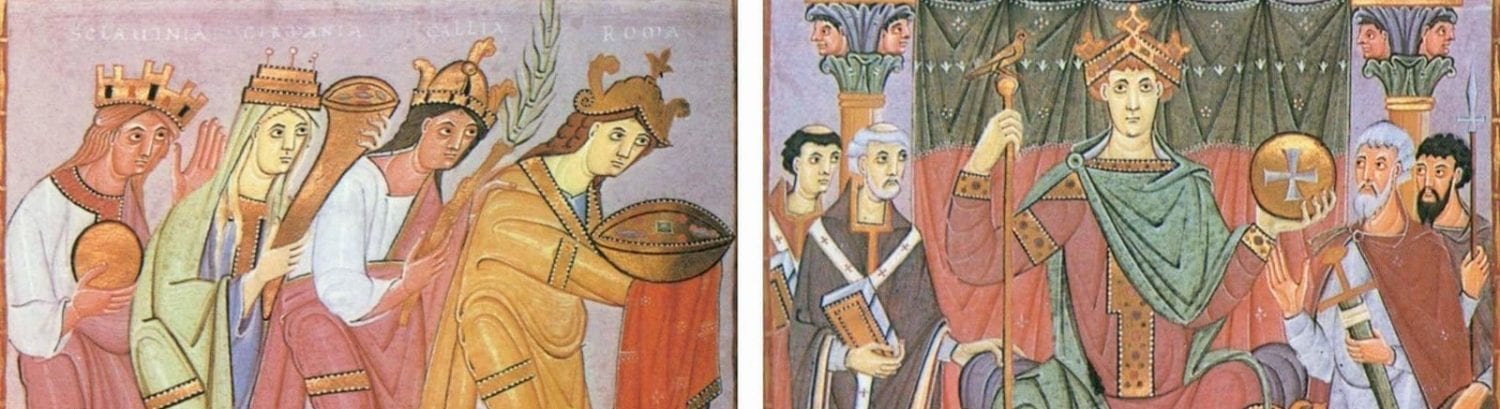

Roman Rule to Ostrogothic Control

Rising from a village to a colony, the city of Pavia fluctuated between cultures until settling as a center for Ostrogothic control[9]. While in power, the kings of the Ostrogoths, specifically Theoderic, began restoring Pavia and developing new Roman architecture such as baths and amphitheaters around the city[10]. The melded contrasts of the Gothic rule and Romanesque development defined the dichotomous culture of Pavia during the rise of barbarian management. Pavia’s mix of peoples and beliefs provided a potent platform for writers to contend over the controversial issues of barbarians, Christianity, and their possible integration(see below).

Boethius

Literature, of course, is an important component of culture. Perhaps Pavia’s most famous contributor to literature in the early Lombard period was Boethius (c. 477-524), who composed one of his most famous works, The Consolation of Philosophy, while imprisoned in Pavia. [2] Boethius had been accused of conspiring against the Gothic rule in Italy and attempting to restore Roman/Byzantine control and was eventually executed for this by order of Theoderic. [3] Regardless of whether or not the charge was true, it demonstrates that in the time shortly following the Gothic takeover of Italy there was significant fear and distrust between Rome and the Goths. It may have only been at the level of high politics, but it would be unsurprising for the Roman population and the new Gothic peoples to be distrustful of each other, creating a volatile culture. Boethius was classically trained, and his works are studded with allusions to Greek and Roman literature, [3] showing that despite a Gothic political takeover, Roman culture was still very much alive in the early 6th century.

Marcus Felix Ennodius

While some writer such as Boethius despised the rise of the Gothic rule, some writers embraced the conversion of Pavia. One of these writers, Ennodius of Pavia (c.471-521), was appointed the papacy in 507[11]. In the same year, he composed a panegyric on Theoderic which contrasted the despised despot picture drawn by some writers like Boethius[11]. In one translation, Ennodius writes in his seminal work, The Panegyric of Theoderic, the Ostrogoth king has a “sweetness of civilitas”[12]. In addition, Ennodius wrote heavily on the possibly salvageable relationship of Roman paganism and Christianity emphasizing another mix of cultures enveloping the former pope[12]. He, like Boethius, contributed to the diversity of discourse all emanating from the city of Pavia.

Lombardic Capital

San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro

San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro is a Pavian church dedicated to St. Peter. The name means “St. Peter in the golden sky,” which refers to the gold plating on the modern church’s ceiling, but it is believed that the original structure had gold paint on the ceiling and shared the name.

It is notable for holding the body of St. Augustine, which was brought to the church by King Liutprand in the 8th Century. [4] It is likely that he did this to bring further prestige to the Lombard capital, which demonstrates that having relics was important to the culture and image of the city. Having these relics would likely have drawn a cult of St. Augustine to Pavia, which would bring even more religion into the culture and atmosphere of the city. We can see that gold was used in the art, an extravagant material, in a church that was chosen to house an important relic, implying that the Lombards viewed gold as a symbol of wealth or beauty, just as we do today. It is also worth noting that by this time, the Lombard kings are fully supporting Catholicism, in contrast to the Arian Goths who ruled Italy in the early Medieval era.

San Michele Maggiore

The San Michele Maggiore is the first church named after Saint Michael [5]. During this time period in Pavia, churches were very important culturally because the Lombard kings had converted to Christianity. The San Michele was built on the location of an old Lombard Palace chapel and is considered one of Pavia’s most important churches. The architecture of the San Michele is standard for most Lombard Churches. Medieval Lombard kings would go to the San Michele to be crowned, and famously Barbarossa was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in the San Michele in 1155 [6]. A coronation in the San Michele is a large event that would be important to both local people from Pavia and to outsiders who were under the same rule. This would be one of the largest events of many locals lives, and by having the San Michele be the location of the coronation adds to the importance and prestige of the San Michele.

In addition to being an important location during coronations, the San Michele also has lots of intricate artwork inside of it. One example of this is the labyrinth in San Michele. The Labyrinth has four animals (a goose, a flying horse, a dragon and a goat) and in the center a depiction of Theseus and the Minotaur. Also, there is a depiction of the battle between David and Goliath from the Bible. In this depiction, David has the same exact club as Theseus which shows that the original artist behind this labyrinth is attempting to parallel the story of David and Goliath with Theseus and the Minotaur [7]. This artwork shows that people in this time period would be familiar with some myths from Greek mythology and also that having murals like this labyrinth was fairly commonplace in churches. This large piece of mosaic art work shows the emphasis on the interior of churches being fancy and fashionable with some very intricate pieces of artwork.

Another piece of art in San Michele is Teodote’s crucifix. This three-meter crucifix is still in San Michele

today and experts have dated it back to around the 10th century but possibly earlier even than that. This crucifix is made of wood but has a silver layer on top of it and has various intricate gildings and designs on it. [8] Such a large crucifix shows some of the shifting values in Christianity during this

time period. Churches and monasteries appear to be more ornate and not as basic and plane as they were in earlier days. This almost excessive three-meter tall crucifix is a perfect exam ple of the shift to churches being places with large displays of art and more flashy decorations.

ple of the shift to churches being places with large displays of art and more flashy decorations.

Bibliography

- Bullough, D. A. “Urban Change in Medieval Italy: The Example of Pavia,” in Papers of the British School at Rome, vol. 34, p. 82-130. British School at Rome, 1966.

- Chadwick, Henry. “Theta on Philosophy’s Dress in Boethius,” in Medium Ævum, vol. 49, no. 2, p. 175-179. Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 1980.

- Lerer, Seth. “Introduction,” in The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. David R. Slavitt. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008.

- LoGerfo, James. “A Progress Through Northern Italy,” in Contemporary Review, vol. 267, issue 1559, p. 305. Contemporary Review Ltd, Oxford, UK, 1995.

- “San Michele Maggiore.” Pavia Tour, 17 Mar. 2015, www.paviatour.it/en/2015/03/san-michele-maggiore/.

- “Basilica Di San Michele | Pavia, Italy Attractions.” Lonely Planet, Lonely Planet, www.lonelyplanet.com/italy/pavia/attractions/basilica-di-san-michele/a/poi-sig/1049770/359949.

- Matthews, W H. “Loyola University Chicago.” Mission and Vision: Mission & Identity, www.luc.edu/medieval/labyrinths/maggiore.shtml.

- Paolo_Toffanin. “Crucifix Teodote , Kept in the Millenary Church of San Michele in…” Getty Images, www.gettyimages.com/detail/photo/crucifix-teodote-church-of-san-michele-pavia-royalty-free-image/612853120

- Barnish, Sam J. The Ostrogoths from the Migration Period to the Sixth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. Page 18. Accessed March 9, 2019.

- Tittler, Robert, and David Nicholas. A History of Urban Society in Europe. from Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century. London: Longman, 1997. Page 36. Accessed March 9, 2019.

- Barnish, Sam J. The Ostrogoths from the Migration Period to the Sixth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2007. Accessed March 9, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=92zXAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36&lpg=PA36&dq=public roman baths pavia&source=bl&ots=uzKJKoO92G&sig=ACfU3U2cVTfj-ggIzcbxpoFhpSsbW8iUkw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj22PLG9fjgAhVB8IMKHb_vDEgQ6AEwE3oECAEQAQ#v=onepage&q=public roman baths pavia&f=false.

- Arnold, Johnathan J. “Theoderic, the Goths, and the Restoration of the Roman Empire” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 2008. 106-107. Accessed March 8, 2019

Images

Image of Boethius

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boethius#/media/File:0372_-_Pavia_-_S._Pietro_-_Cripta_-_Tomba_Boezio_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto,_Oct_17_2009.jpg

Image of Lombard Jewelry

http://7aese.eucentre.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Pavia-Town-of-Art-Cradle-of-Culture.pdf

Image of San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro: original 2007, edited 2014. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Focus_on_the_Ceiling_of_San_Pietro_in_Ciel_d%27Oro.jpg

Image of the labyrinth in the San Michele

https://www.luc.edu/medieval/labyrinths/maggiore.shtml

Picture of the San Michele Maggiore

http://www.paviatour.it/en/2015/03/san-michele-maggiore/

Image of Teodotes Crucifix

https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/photo/crucifix-teodote-church-of-san-michele-pavia-royalty-free-image/612853120

· Permalink

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/866342.pdf?refreqid=search%3Adc4bc5e5c9c2a648c09d4e09158f5796

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/870108.pdf?refreqid=search%3A141d81cc1669bc8235f82794f344224f

A couple of potentially useful sources.

· Permalink

Hiya guys!

Here are some sources for historical background to give context to artists:

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/05/eust.html

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/eust.html

· Permalink

some info about churches in this time period and specifically San Michele which is built on the location of the Lombard Palace chapel. Place of coronations ect. at least according to wikipedia =(

looks like kings were crowned here which would be a large ceremony ect. big event for people inside and outside of pavia. and this kind of establishes Pavia as important and as a culturally important center in these time periods.

“burned down in 1004”

“The Basilica of San Michele Maggiore is a church of Pavia, one of the most striking example of Lombard-Romanesque”

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:0738_-_Pavia_-_San_Michele_-_Affresco_transetto_sin._-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto,_Oct_17_2009.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Michele_Maggiore,_Pavia

some more non wikipedia information

https://www.luc.edu/medieval/labyrinths/maggiore.shtml

https://www.lonelyplanet.com/italy/pavia/attractions/basilica-di-san-michele/a/poi-sig/1049770/359949

· Permalink

Hey I just moved the Boethius section to before the Lombards because he is right on the cusp of Lombard takeover

· Permalink

Thanks, good call.

· Permalink

Also, I will add Ennodius as a foil to Boethius to emphasize how split the population was on the acceptance of barbarian culture.

· Permalink

Also, the metalwork comment made in Bullough’s paper was about the Ostrogoths so I’m going to move it up and hopefully find a picture to compliment it

· Permalink

Somehow just deleted all of mine. luckily had a backup saved. almost had a heart attack… big night

· Permalink

Trying my best to put that barbarian influenced metalworking into the page without triggering a butterfly effect of formatting terror.

· Permalink

If anyone can do it then please do its terrible

· Permalink

Well, I guess my editing overlapped with one of y’all and now some of my work is gone. Wish this was a little more dynamic