Since first gaining international acclaim with the landmark 2005 film Paradise Now, Ali Suliman has been a force of nature for Arab film, turning in a string of powerful, nuanced, and naturalistic performances across countries and genres, as well as appearing in Hollywood blockbusters directed by the likes of Ridley Scott and Peter Berg.

He is, quite simply, one of the best actors alive today, who has made the realities of life as a Palestinian clearer for film fans across the world.

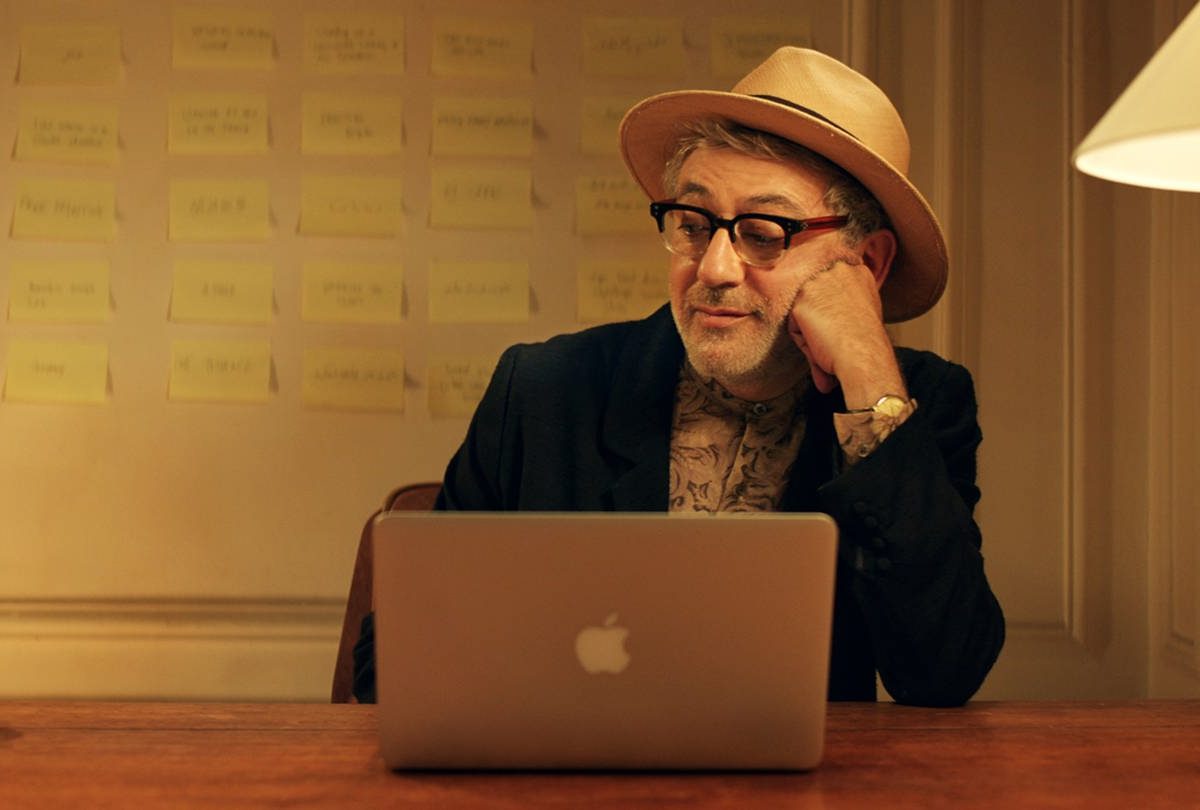

Suliman spoke to Esquire Middle East about his astounding career thus far, the filmmakers he’s worked with, his approach to his craft, and more.

Here’s Esquire Middle East‘s list of 10 great Palestinian films to watch right now (for free).

Read our our conversation below:

Why did you want to get into acting?

I always wanted to be an actor. Since I was a little kid. I grew up the youngest son in a big family. I had 11 brothers and sisters, so I was like the clown in the house—the little toy of the family. I had to entertain them. As I grew up, I had another brother go to acting school and I was always watching him, and I wanted to be like him. I was sure that I was going to be an actor. After I finished high school, I went to the acting school to study.

Were you always confident that you would succeed?

I wasn’t confident—I just did what I liked. I didn’t think that way, I just wanted to do what I love. I followed my instinct, that’s all.

What were you doing before Paradise Now?

I worked in the theater, actually, doing small roles.

How was the Syrian Bride?

That was my first experience in cinema. It was a bit different, because at that time, I didn’t like the cinema that much. I had no experience, I didn’t really know this media, so playing in front o the camera was weird for me. I love the theater more, I love the inteacting between the audience, acting and getting an immediate reaction. Since I started to explore the effect of what cinema can do, and you can reach many audiences the same moment.

Paradise Now was all over the world—it was distributed everywhere. I went to Japan and people really saw it there.

How did you find Paradise Now in the first place?

I did an audition, and after I made the audition in Nazareth, my hometown. Hany Abu Assad was looking for actors there, and I got the role immediately after the audition. It was a great answer, but when I got the script and read it, I said, ok, I have to think about it. It was a really difficult subject at that time, and to speak about it this way, I said, listen, I am really in the beginning of my career, I don’t want to end it with this movie. I was sure this movie would close all the doors in front of me and nobody would accept it because of the subject matter. No one really had the courage to deal with this subject before.

You were scared to be labeled a terrorist sympathizer?

Exactly. And that’s what happened with the Academy Awards, some people really went against the film and started going out into the street to stop the nomination in the Oscars, but it didn’t do anything in the end—we won the Golden Globe and we were nominated for an Oscar. In the end, it was the opposite of what I thought. I was happy because I was so mistaken.

When did you know that Paradise Now was really a movie that people connected with?

The opening was at the Berinale Film Festival, which was the first festival I had ever been to. The whole festival was talking about the film. If films can’t create conversation, what is it for? Films should make people think about things that they have questions about, that they have doubts about.

Did Hany have to convince you to take the film at first?

He didn’t convince me. I wanted so much to do this, of course, and when I read the script, this doubt was between me and myself. I didn’t share it with anyone. On the one hand, you want the opportunity. On the other hand, as an actor, you don’t have that many opportunities in Palestine. We have barely any movies, and we don’t have an industry, we have filmmakers, we have talent. When you get an opportunity, you need to get it, otherwise someone else will.

While we were shooting, the media was around, and were interviewing us while we were shooting. I had never seen this before in my life, such a big noise while we were shooting. Many of the TV channels were coming to sit and interview us while we are shooting because they are really interested. It started to make noise then. I started to feel where it would go, somehow.

What impresses you about Hany as a filmmaker?

It was the first time I worked with him, and as a young actor, for me, it was incredible. Hany, his way, is a bit different. He’s choosing you because he trusts yo, because he saw that you can be the character. What he did in Paradise Now, for example. We shot in the West Bank. It was my first time going there.

While we were shooting, for three months, Hany put us there, and we lived there. It was around the second intifada, I remember. There was a siege, there were soldiers around, there were wanted people, and sometimes bombs and fights. Some nights we couldn’t sleeps from the gunfire that you can hear in the distance. It was really scary. So he put us there, and the character that I played, he’s supposed to be a mechanic. We started to go to practice this, every day going to work as a mechanic. We went with our toolbelt, took a cab, and worked for eight hours a day at the garage. One day Hany came in the middle of the week and asked the mechanic, what do you think about the guys? Are they good workers? He said “this guy? He’s a great mechanic, I want to hire him! But this other guy? He can sell flowers!”

How would you describe your approach to acting?

I like to live as much in the world that the character lives in, to try to develop it, and make a clear line between my character and the character itself that I played. To separate yourself from the character, and at the same time, to be connected to them. It’s a thin line, but at the same time, it’s a thick line. You have to know that you’re an actor somehow. It’s something we learn in acting school. You have to be connected to the character to bring their universe, their history and their soul. You have to connect their feelings to your feelings.

Lawrence Olivier could cry his soul out and not feel anything. This is technique! I took something very important from what he did and what he said. Sometimes I bring from technique, sometimes I bring things from my soul.

How has your process as an actor evolved over the years?

It’s a good question actually. It’s really depends of the character and how emotional the part is. It really depends on how far, and how deep you can go with a character. I don’t keep every character with me after shooting. If every character stayed with me after every film, I would lose myself. I have to draw a line between me and the character. When it’s over, I always have to come back to myself.

Do you find it easier or harder to keep that balance at this point in your life?

Now, when I’m not focused on a project, I’m focused on my kids. There is no room to focus on something else.

I remember my first Shakespeare lesson, the director brought us to a vegetable market to observe people in the street. I realized that we created characters from our lives. We are observers. In my daily life I still watch and observe to see the way people are. You don’t stop learning. I often write things for myself because you never know when you’re going to use it, or when you’ll be able to bring something to another character in the future.

In which roles was it most difficult to keep that line?

I almost lost it in Zinzana [(2016), Directed by Majid Al Ansari]. The character is so multifaceted, and I just felt myself drift into it. I started losing myself, started to really dive deep. With this character, I touched every corner. I really enjoyed the moments. I enjoyed it! And at some point, slowly, as we got closer to the scene where he is lit on fire, the last two weeks were hell for me. I went from dancing, doing whatever I want, feeling that nothing can stop me, and then all of a sudden I was covered in prosthetics, I couldn’t hear, I couldn’t see the camera, it was hell. It was almost like I went crazy. I couldn’t speak with people for the last two weeks—i told people ‘don’t touch me!’ It took me a few weeks of time to myself to get my head back.

Do you still feel the lingering effects of that character?

No, of course not. After the shoot, I tried very hard to get back to myself. But when you do this for 13 hours a day every day, waking up at four o’clock in the morning, shooting in a dark and claustrophobic set in the winter, for a month and a half. Imagine what kind of feeling you can contain inside of you! You become a little bit depressed. For the first week it was really nice, but it descended from there. One day it was really rainy and cold, and we were at lunch, and the sun came out and I said, guys! Let’s not shoot! Let’s take the whole crew out! To feel the sun, to feel the nature, gave us a lot of good energy. I was proud that I suggested this.

So after Paradise Now, you started getting pulled into Hollywood films. How was that transition for you?

It was bigger than I was imagining. I was thinking about theater—that was my dream. I never dreamed of cinema. But when it came, it came too fast, and too big. For me, the first project that I started in Hollywood was The Kingdom with Peter Berg. It was the shock of my life to work on such a big film like that. They had five cameras, 35mm film, shooting all at once. We went from a low budget movie with one or two takes to a much bigger production. It was insane for me—I was really in wonderland. It was one of the best experiences I ever had. I spent four months there, and it was shocking to learn how professional they are. I’ve never met people as professional about the Americans—it’s business on set. They’re so serious about it—you can’t even laugh on set. Afterwards, you can laugh with everyone, have fun, but on set, everyone’s doing their job, everyone is serious and dedicated, and you can see it. For me, to shoot in almost a city that they built just as a set. They closed a highway for two weeks just so we could shoot—all the cars on the road besides ours were just extras! I couldn’t believe it.

Peter Berg—the way he shoots is very different from any other director I’ve worked with. First of all, we did one week doing intensive study in how the FBI gathers and handles evidence. After that we learned how to shoot guns, as I was playing a policeman. Before that I’d never in my life carried a gun, I’d only seen guns held by soldiers at checkpoints.

I shot with Peter twice—on The Kingdom and Lone Survivor.

How were things different on Lone Survivor?

It wasn’t much different. His way is the same way—he’s an incredible genius. He is an actor, and he knows how to deal with actors. And this is the best, I think. He’s always listening. If you have something to say, he listens to you. And if you convince him, he’ll buy it.

How was Ridley Scott?

It was incredible. I remember doing the audition, and I wasn’t expecting him to pick me. I thought to myself, ok, I’m in Los Angeles, I’ll try it, and so I did it and went home. Then all of a sudden I got the call and was told that I was accepted for the role. They said, ‘Body of Lies!’ I asked, ‘What’s Body of Lies? I can’t even remember!’ The told me it was Ridley Scott and I couldn’t believe it. ‘What? No! Yes!!!’

We shot in Morocco, and it was incredible working with him. He’s such a minimalist with his direction. He comes and tells you something quickly and that’s it, he’ll go. Sometimes I couldn’t even follow his English! But it was incredible working with him.

Ridley Scott has a different way than Peter Berg. He’ll give you direction very easily and quietly, and he won’t speak to you again. When the scene is finished, he’ll come to you and tell you what he thought of it. He didn’t even do rehearsals! Or maybe he just didn’t do them with me…

I remember, while were shooting American Gangster had just come to theaters, and he did a screening for us. And at one point we were shooting in the old part of the city, and he was walking and saw a guy with a little table and lots of pirated DVDs for sale. And there, sitting on the table, was American Gangster! Ridley Scott was so mad, he wanted to take him to the police! We stopped him like no, no, that’s just how it works here! But he was so serious, and I understand that, you know?

What sort of projects do you say no to?

I say no to stereotypes. Even though, with any character I do, I put my own perspective in the character, if it’s really a super stereotype or cliche, I just don’t take the role.

How was working with Ali Mostafa on From A to B and the Worthy?

On From A to B, it was more of a supporting role, and I came to support an Emirati filmmaker. With the Worthy, I had more time to work with him. What I saw on that set was how he worked with equipment, and he’s really good at dealing with equipment, cameras, and digital effects. He’s super talented. It was super cool, I think, yeah.

And Majid Al Ansari, director of Zinzana?

I met Majid while we were shooting From A to B. He had a small job on the movie, and we met there one night at a party and we started to talk about cinema, and he told me, ‘I’m going to direct my first feature next. Would you like to be with me?’ I said, ‘sure, why not!’ I thought it was just small talk!

Then I got a call from his producer Rami Yasin and he said that we’re in a rush, can you please read the script for this film. I said I was busy running to be on the jury of the Abu Dhabi Film Festival and he said please read it on your way. I read it on the airplane, and as soon as I landed in Abu Dhabi I called and said, ‘I’m in!’ At that time, I couldn’t remember the name of that filmmaker I met, and I had no idea that the guy I met on From A to B was this guy!

When we first started, I met him and I said, ‘Ah! I remember you! Wow…you were serious, I guess! OK!’ [laughs].

With Majid Al Ansari, it was a process, but it was a process for good. We started talking about the characters, and I knew that this guy was so into it. This is the difference between Ali Mostafa and Majid Al Ansari. Both are amazing for me. When I look into Majid’s face…he was my inspiration for the character the way. When he talked about the character, I could see the character in his eyes! I told him, you’re supposed to do this role, not me!

When I worked with Majid, I trusted him from the moment we started. I saw how into this genre he was. It’s a bit far away from my tastes, but it was an amazing experience for me—I started to love it. Majid likes to work with his actors. He follows every detail about the character, and, at the same time, he understands technique. I felt like I was really connected to this guy, to this brain, and I felt he really deserved my trust. He was the captain, and I felt safe in his boat. I really did my best because he was there for me.

The character I play in The Worthy I love. There were times when filming the Worthy where Ali would say to me, believe me, at the end you will like it. He has vision, but at times I couldn’t follow his vision because I was stuck trying to work on the character. I wanted to develop the character, and I was successful in bringing in many elements that weren’t in the script, as the character wasn’t as strong in the original script.

Do you feel, looking at Zinzana, that you are most proud of that performance?

Every single movie I did, it was my best work. When I am working, I put my soul into it. Even if it’s just a small character. For each character I play, it’s the best I could do. But with Zinzana, I had the opportunity to do something that I never did before. This was the most unique character I ever played in the cinema.

Does acting fulfill you in the same way it did when you were first acting in the theater?

I love acting, no matter what. I love this profession. Now, I’ve started to see how difficult it is when you have a family of your own. When I was young, acting was the most important thing in my life. This is why I exist. But today, I have another heart—my acting career, and my family. To do the balance between these things is hard. I just finished a new series that I shot in Spain and Cardiff for four months, and though I still love it, it was difficult to be away from them. I feel the magic of cinema, and the effect of a big screen on an audience, but I still have the need to do theater. The theater is the very basics of acting. If you only do cinema, your skills become routine, so you have to go back to theater to refresh your skills. It’s like taking your car in for service.

Were there any films you auditioned for that you regretted not getting?

Tyrant was difficult. I did three auditions, and I got the call from my agent saying they wanted me for the role. I had high expectations for the first time—they flew me to London, I met with David Yates, who is an incredible guy. I felt sorry that I didn’t work with him, because he’s really amazing. We sat together in London and talked about the character and he told me how happy he was that I was the one in this part. But then the studio called and said, Ali, I’m sorry, they want another guy. I said, I just talked to the director! Did he kick me off the project? Then I got a call from David Yates and he apologized and said, listen, it’s not in my hands—it’s the studio. They didn’t want me!

200 Meters is, in my opinion, perhaps your best work. How did you connect with the project?

The producer May Odeh is a good friend of mine. She talked to me about the project, and told me she had a great script for me. I met with Ameen (Nayfeh, the film’s director) and he told me how this story is a part of him, because he himself was separated from part of his family on the other side of the wall.

That wall was built in 2004 or 2005, and before that there was no border. When it was built, all of a sudden he was away from his family, and he couldn’t visit his family in the other part. It was such a personal story.

Besides this, it was written extremely well, with a strong narrative and drive for the character. I saw human need in this story. It’s simple without any cliché or political pronouncements—it’s the story of a man named Mustafa who is trying to reach his family on the other side of the wall. That’s what I loved about this project, that from beginning to end all he wants to live freely, to live without obstacles that he can face in his daily life. It’s a simple story.

With films about Palestine, I think there’s often a pressure on filmmakers to try to cover everything, to teach movie-goers about the entire history, or to make a grand explicit political statement. One of the great things about having so many great films on Palestine is that it’s easier to stop worrying about that pressure and zoom in on one guy and what he goes through on one day.

In 200 Meters, everything doesn’t need to be explained for people to understand, and because you’ve zoomed in and made it so specific, it’s even more universal and easier to get into this character and this struggle.

Exactly. You said it exactly the right way. When we were shooting in the streets, I heard so many stories about people, real people get separated by the wall and their family is living on, the other side of the wall. That made people really involved with this story behind the camera. We didn’t have to work on making political statements in the film because it’s there. We didn’t have to try hard to bring it out or work on it. It’s just there in the reality of this man’s story, as it’s the story of so many.

What was it in this character that you personally connected with, and allowed you to find a way into him?

It’s that he needed to be to be with his family. It’s something that you really can’t understand when you don’t live in a situation like that. I still don’t understand it fully, but for example now, I’m in the Dominican Republic filming a movie, and I’m a 15 hour flight away from my kids. But even then, whenever I want to I can see them, I can bring them here, they can be with me. I’m not limited like Mustafa is, even though he’s so close to them in physical distance. He cannot go wherever he wants to see his family. No matter how much I try to understand, I still can’t. I’m not in his situation. I can put myself in that mentally for a short time while in the character, but deep down I can never understand what it’s like to live like that fully.

There’s also a range of emotions here. The film has a lot of humour, which you wouldn’t necessarily expect on its face.

In my eyes that is the real life of Palestinian. They are under occupation, they are suffering, but at the same time, they have a humor. This helps them really survive, and what keeps them like motivated to keep living.

What was your relationship like with Ameen while filming?

The first thing Ameen told me when we met is that he was writing the script over seven years in Canada to really develop it properly. And when he started to write the script, he was thinking of me. There was big chemistry between me and him, even before we met. He is very talented and the communication was really perfect between us. And like, we were synchronized somehow.

I didn’t feel for a moment that this was his first feature film, and I felt that this guy is really talented that he is really aware of every single shot that we were doing, even on a shortened shooting schedule. We filmed everything in 22 days on many locations, and we had to keep moving an entire crew. Sometimes it was tense but we really did make it through because of him.

What are the things you still dream of doing in your career?

I just did one of them with Mark Wahlberg, in an adventure movie with a character who is really so different from me. I never thought I would be able to do this. But I have a strong desire to write my own story and direct it or produce it. It’s not that I want to direct, but sometimes you need to tell your own story, and sometimes you’re the only one that can understand yourself.

I have many ideas, and I’ve been doing research about many things. The problem is I need to find the time to sit and start to turn these ideas into scripts, and to make them happen, and the problem is I don’t have that time.Time is really the only necessity. Or perhaps I can find a writer. My priority is my work as an actor, Btu there are many dreams out there. I know that one day I will find the time, and I will have to make them happen.

Esquire now has a newsletter – sign up to get it sent straight to your inbox.

Want up-to-the-minute entertainment news and features? Just hit 'Like' on our Esquire Facebook page and 'Follow' on our @esquiremiddleeast Instagram and Twitter account.