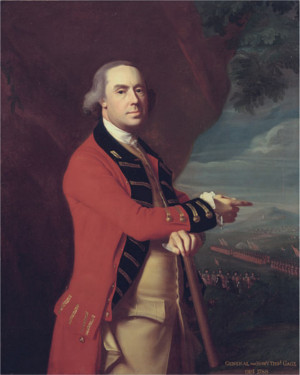

General Thomas Gage, painting by John Singleton Copley | Wikimedia Commons public domain image.

Early Life

Thomas Gage was a British General known for his service in the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War. The second son of a Viscount, he was born in 1719 or 1720 in England, This nobleman’s status would serve him well in life, as his brother, who succeeded their father as viscount, used his power to advance Thomas’ political and military standing.

After his schooling, he joined the British Army. He bought a lieutenant’s commission and served in the British Army, transferring Regiments and moving up in the ranks and seeing much action until his eventual promotion to lieutenant colonel.

Thomas Gage was popular in the army and in the club he was a member at, charming and handsome. His time in college, in the club, and as a nobleman’s son gave him opportunities to create powerful political and military allies. He was engaged at one point, but it was broken off. He and his father both stood for seats in parliament in 1753. He didn’t get the seat and contested the results but withdrew his protest when his regiment was sent to America to fight in the French and Indian War.

French and Indian War

In the French and Indian War, Gage’s regiment was part of General Braddock‘s expeditionary force driving French forces from the much fought over Ohio Country. Gage took temporary command during the Battle of the Monongahela when the commander of the regiment was killed, but complaints that his poor tactics were responsible for the failure and retreat of the company denied him permanent leadership.

It was during this battle that Thomas Gage first met George Washington, and the two were friendly for several years, however time and distance and the growing enmity towards Britain led to Washington publicly denouncing Thomas Gage’s taking authority in the field.

Margaret Kemble Gage | painting by John Singleton Copley | Public domain image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

He continued fighting in the French and Indian War and even created a light infantry regiment. Between recruiting for an upcoming campaign and fighting, he met and married Margaret Kemble from Brunswick in 1758. His recruiting was successful, but the campaign was not. A mere 4,000 French defeated the British forces numbering 16,000 men. In spite of the massive failure, Thomas Gage was promoted to brigadier general following the battle.

As a new general, he was placed in command of a post in Albany and shortly afterward was ordered to take control of the recently acquired Fort Niagara, whose General had just died, to take Fort La Galette on Lake Ontario, and, if possible, to also advance on Montreal. However, when Gage arrived at the Fort La Galette, he decided the number of troops were not enough to take it which angered his superiors.

Governor

After the French’s eventual surrender, Thomas Gage was named the military governor of Montreal. His wife Margaret came to live with him in Montreal and his first two children were born there. He proved to be a fair administrator, but after the excitement of war, he grew tired of his posting. His superior was on leave in England, so Gage was excited to receive the post of acting commander-in-chief of North America.

He was not expecting the sudden trouble from the Indians that followed. Pontiac’s Rebellion, as it became known, was incited in part by the strict policies forbidding the sale of ammunition to the Indians from the British and in part by the British colonies continually spreading into Indian land. Indians made several attacks on some of the British forts, sometimes successfully driving away the people. Thomas Gage is responsible for sending officers to negotiate peace treaties and Pontiac’s Rebellion was ended in July 1766.

When his superior announced no plans to return to America, Thomas Gage was named the official commander-in-chief. Stationing himself in New York, he used his advantageous and relatively well-paid position to advance family members and close friends’ careers as well as send his six children to school in England.

It was during Gage’s tenure that the growing unrest of the colonies grew. He began drawing in troops from the frontiers to fortify larger colonies like New York and Boston, which created a growing need to feed and clothe the soldiers. Gage thought that the general unrest surrounding the Stamp Act was coming from a select few in Boston and sent two regiments to occupy Boston, inflaming an already upset city. The Quartering Act of 1765 passed by Parliament required that the colonists house the regiments.

Gage began to realize that democracy was “too prevalent” in America and that having their own government was undermining the British Parliament’s authority. He took his family to England in June of 1773 and therefore missed the Boston Tea Party that December. The following measures Parliament took, the <a href=”intolerable-acts.html”>Intolerable Acts</a>, were meant to strike back at the colonies and in part were originated with Thomas Gage, who was the man chosen to take care of the situation growing in the colonies and enforce these new Acts.

Military Governor

In 1774, Thomas Gage was named the appointed military Royal governor of Massachusetts. The Bostonians were happy to see their old governor leave, so they were happy to see Gage at first, but when he began enforcing the Intolerable Acts, The Boston Port Act, and the Massachusetts Government Act, his popularity rapidly diminished. Upon discovering that Massachusetts was sending representatives to the Continental Congress, he dissolved the Assembly and set up a “Governor’s council.” The people refused to meet with the council, but he successfully bought the political leader Benjamin Church who gave him information regarding the rebel leaders.

Gage collected his forces in Boston, withdrawing garrisons in New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia and ordered the army to confiscate guns, powder, and weapons, specifically targeting a magazine in Somerville. The rebels reacted, calling the militia to march on Cambridge but they eventually dispersed. His mission was successful, but he was much more cautious of the colonists, drawing criticism from other officers. Gage was afraid that in order to take down the rebellion, he would need more troops, “for to begin with small numbers will encourage resistance, and not terrify; and will in the end cost more blood and treasure.”

Finally, Britain had had enough and Gage was ordered to take decisive action. He had received intelligence that Concord, MA was being used to store weapons. He sent a troop to march there, leading to a skirmish in Lexington, but little was found when he reached Concord as Gage’s plans had reached the Patriots and the weapons had been moved. On leaving Concord, rebel militia attacked the British column. The Battles of Lexington and Concord caused the British more casualties than the rebels. The colonial militia, emboldened by their successes, set siege to Boston, led by General Artemas Ward.

It was speculated that Thomas Gage’s wife, Margaret Kemble Gage, had passed information to the Patriots, spying on her husband and passing intelligence regarding the Lexington and Concord battles to Joseph Warren. While the evidence is entirely circumstantial at best, her husband did send her to England in the summer of 1775.

Gage received reinforcements along with General William Howe and brigadiers John Burgoyne and General Henry Clinton with whom he collaborated concerning the Siege of Boston and fought with at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Thomas Gage wrote to England with the results of the battle. Within three days, they wrote back replacing him with General William Howe. Thomas Gage left for England where he was the object of both ridicule and compassion for his failure to squash the rebellion. He was reinstated briefly and promoted to General during a possible French invasion in 1782. He eventually died in 1787.