Talking Heads’ Jerry Harrison: Life During Studio Time

The musician and producer on the enduring brilliance of Stop Making Sense, what he learned from Eno, getting great-sounding records across a vast range of music, and more.

by Elisabeth Vincentelli

In both the motion-picture and music worlds, concert films are a distinct subgenre with a storied history, and few of them are as beloved as Stop Making Sense. Jonathan Demme’s 1984 movie is a brilliantly edited document of Talking Heads at the peak of their musical and theatrical powers (frontman David Byrne storyboarded every song), and it spawned an equally popular soundtrack.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the December 1983 performances seen in the film, a 4K restoration is hitting IMAX and other theaters, while the soundtrack is back as a deluxe reissue. That new edition includes two previously unreleased tracks, “Cities” and “Big Business/I Zimbra,” plus a Dolby Atmos mix overseen by the band’s keyboardist and guitarist, Jerry Harrison, and longtime Heads engineer ET Thorngren. Last year, Harrison and Thorngren released their Atmos mixes of the group’s studio catalog.

After laying the foundation for punk in Modern Lovers, Harrison joined Talking Heads in 1977. In the early 1980s, mirroring his bandmates’ ambitions, he launched a parallel solo career that includes such excellent art-groove albums as The Red and the Black (1981) and Casual Gods (1988), which boasted the hit single “Rev It Up.”

Harrison had been getting into studio work while still with Talking Heads, and in 1981, he dove into production with the bouncy Nona Hendryx single “Love Is Like an Itching in My Heart.” Since then, he has been behind the soundboard for the diverse likes of Violent Femmes’ The Blind Leading the Naked (1986), Crash Test Dummies’ double-platinum God Shuffled His Feet (1993), Live’s eight-times-platinum Throwing Copper (1994), Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s platinum Trouble Is… (1997), No Doubt’s single “New” (1999), the Von Bondies’ Pawn Shoppe Heart (2004) and Le Butcherettes’ bi/MENTAL (2019).

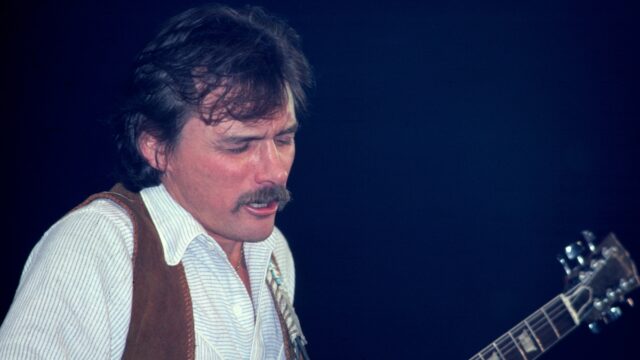

Harrison, 74, has recently been performing Talking Heads’ music live alongside guitarist Adrian Belew on their “Remain in Light” tour. Born in Milwaukee and educated at Harvard, he’s the kind of person who can dissect technical details but also knows when not to overplay his hand. In a recent chat at TIDAL’s New York office, he noted that much of his work on the Stop Making Sense album was subtle: “When the camera goes someplace, we adjust the mix to show what’s on the screen,” he explained.

This conversation was edited for length, flow and clarity.

Why was Stop Making Sense so sonically distinctive?

I think it is the first live album that has the sort of immediacy and presence of a studio album. Some of it was the brilliance of Eric Thorngren, but there also were new techniques in the studio that allowed it to have a more direct signal. Whereas if you listen to, like, [the Rolling Stones’] Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, it’s a great record, very energetic, but it feels sort of ambient; it’s over there, it’s not punching you in the chest.

You helped expand Talking Heads’ sound. For example, why did you suggest Sigma Sound in Philadelphia to record the vocals on Remain in Light? At the time, that studio was associated with R&B and soul acts.

My first production was with Nona Hendryx at Sigma Sound. Sometimes in the New York studios, there was a kind of snobbishness. You’d go into a studio and an assistant engineer would go, “The Rolling Stones were just here last week.” And you go, “That’s great but that has nothing to do with the record I’m about to make. And if you’re going to be disappointed because we’re not the Rolling Stones, you’re really not the person I want to work with.” We, of course, were also great lovers of the Philly sound, the O’Jays and things like that, and [Sigma Sound] engineers did that stuff. They also had this way of saying, “Here’s a five-minute problem, why don’t you get a cup of coffee?” Or, “This is an hour, why don’t you go out to lunch?” I also have to say that I negotiated a really great rate — I told them they were so known as an R&B studio that we should be a loss leader for them to be able to get rock bands to come in there. [laughs]

How did you become interested in production?

At one point I thought I was going to be a scientist, so the idea of the equipment was really fascinating to me. Working with Brian Eno [who produced three Talking Heads albums, including Remain in Light], there was the idea that the studio was like an extension of your instruments, that these devices weren’t only a way to capture the sound that you made — they were part of the whole process of getting to the end result. Then I sort of eased myself into being a producer. I always hire great engineers, and I rely on them to know more. When we did [Talking Heads’] Speaking in Tongues, Alex Sadkin introduced me to Ted Jensen of Sterling Sound, who was the mastering engineer. By the end of the record, everybody else had left town and I was the only one left, so I went and worked with Ted and finished it. From that point on, I was the one who mastered the records. Sometimes it is taking a long time to get the technical stuff right, but I was enough of a perfectionist that I wanted to do that.

“We wanted to have a good beat and be danceable.” Credit: Hugh Brown, courtesy of WMG.

It’s pretty amazing that Talking Heads’ popularity exploded after the band broke up, and shows no sign of abating.

The movie is a big part of that. The look of the film, all of the lighting, really could have been done a hundred years ago. Nothing was particularly of the ’80s. We were influenced by disco music. We loved R&B. Living in New York at that time, we were in the hip-hop scene. Eric Thorngren had come out of being the engineer over at Sugar Hill. We embraced those elements. But the music is very much our music. We wanted to have a good beat and be danceable.

By the time the Stop Making Sense shows rolled around, in 1983, the touring band had integrated several additional musicians, including keyboardist Bernie Worrell and guitarist Alex Weir. How did that work out?

There’s so many people playing and we respected the spaces, and respected that this was the moment when this person got to do this and this person got to do that. In composing Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues, sometimes we played a part all the way through and we were using the mixing board to turn something on and turn it off. That was the arrangement that we went off of. Things changed and it was organic. Some of the dances that people do with each other, the interactions — a year of touring created those. People are not stepping on each other. With that many people onstage, it’s OK that I’m not really doing anything right now, or what I’m doing is very simple right now. Some musicians just can’t take that — they want to show how adept they are at their instrument.

Is there a secret to working with the wide range of bands on your producing résumé?

Whether it’s the Violent Femmes or No Doubt, I’ve always tried to make it translate well in as many environments as possible. When I was in the Modern Lovers, we worked at a studio that had a little FM broadcaster, and you could go out to your car and listen to the mix — because that was where a lot of people were going to listen to it. If a lot of people are going to listen on headphones, you’d better listen on headphones as well.

We as people have the ability to fill in the gaps; that’s how perception works. And so we can make adjustments for listening on an iPhone or listening on your computer. People of my generation or older generations grew up with the idea of stereos. It’s a new discovery for a younger generation who has grown up listening on earbuds. When they went to the vinyl experience, they finally thought, “Maybe I need to get some speakers.” [laughs]

What was it like producing the garage-punk band Le Butcherettes, which on the surface does not appear to be in your usual wheelhouse?

We talked about the structure of the songs and then we went in and cut them. The unfortunate thing these days is that the budgets are less and you’re in a rush all the time. [Frontwoman Teri Gender Bender] is just such a remarkable talent, and really smart. I think when I first met her, she was reading Wittgenstein. I was like, “What?!” I would love to do more with them. They kind of had a little bit of the feeling of when I produced the Von Bondies.

What was it like to channel the Von Bondies’ energy for Pawn Shoppe Heart?

Again, a lot of it was the fight with a small budget, but they could really play. I think it was gaining Jason [Stollsteimer]’s confidence and him being willing to finally take some suggestions about what he was doing vocally. The most important thing when you produce a band is gaining the trust of each member.