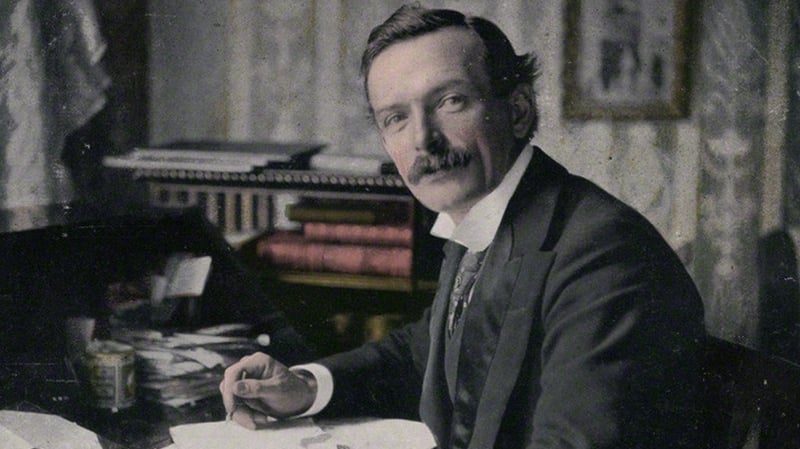

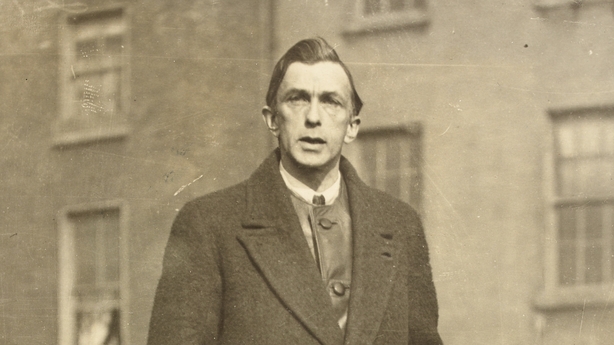

He was the man who had to follow Michael Collins as head of government - and became a surprisingly hardline leader who was prepared to do anything, including enabling executions without trial, to win the war, as Michael Laffan explains

Little was expected of W.T. Cosgrave when he came to power. Despite the differences in temperament between the two men, he was a natural choice to succeed Michael Collins as chairman of the Provisional Government in August 1922. He was the only survivor in office of the administration created by de Valera in April 1919, he was the most experienced member of the cabinet, and he had chaired most of its recent meetings. But his reputation was not that of a warrior, and many people feared (while some hoped) that he would prove a weak leader at a time when only firm measures could win the Civil War.

A hawk, not a dove

One pro-Treaty TD worried about 'lack of direction at the head'. A British observer remarked that the Irish people were not convinced Cosgrave was sufficiently strong to implement the government’s programme. The imprisoned republican commander Rory O’Connor believed that the new chairman would ‘be easily scared to clear out’ – yet he survived in office for over nine years, and he presided over the cabinet meeting that authorised O’Connor’s execution.

The bloodiest phase of the conflict was already passed by the time of Collins’s death, but a long and bitter war of attrition lay ahead, and Cosgrave proved to be a stern and decisive leader, a hawk rather than a dove. He was unaffected by personal losses such as the murder of his uncle or the destruction of his family home and all its contents.

Long afterwards Liam Cosgrave described his father as being ‘quite ruthless’ in defending what he saw as the will of the people. Collins had regarded his republican opponents as wayward and misguided colleagues, but Cosgrave saw them as ‘armed freebooters’, the ‘dregs of society’, an elite who ‘had a grudge against the great mass of the people’.

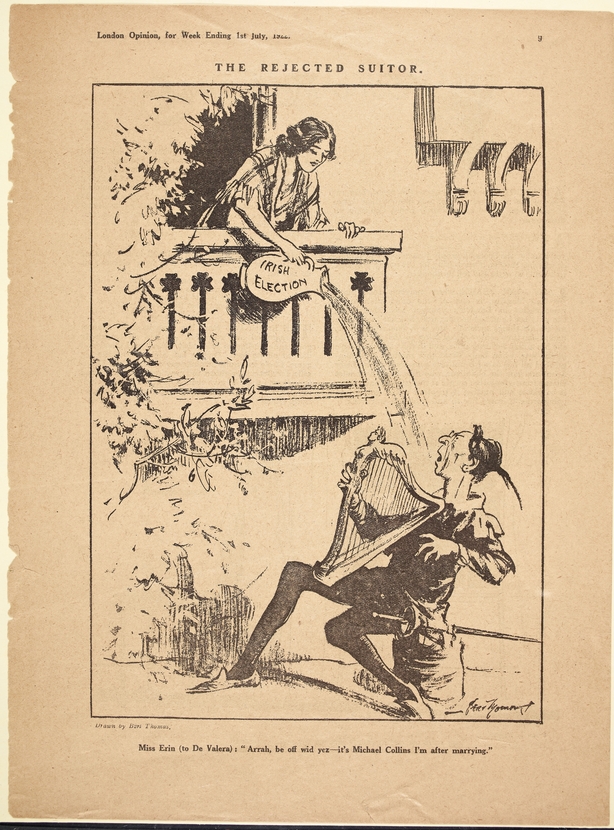

For him the dominant question remained, as it had been before the outbreak of fighting: ‘Is there to be government by majority or is there to be government by autocracy?’ He viewed de Valera with particular scorn – an opinion that remained unchanged over the decades.

The republicans’ attempts to destroy the new state’s economy and infrastructure appalled a man whose approach to politics had always been practical and down-to-earth, concerned with social questions and with efficient administration. He was horrified that what he regarded as quibbles about an oath to the king should result in such hatred and devastation.

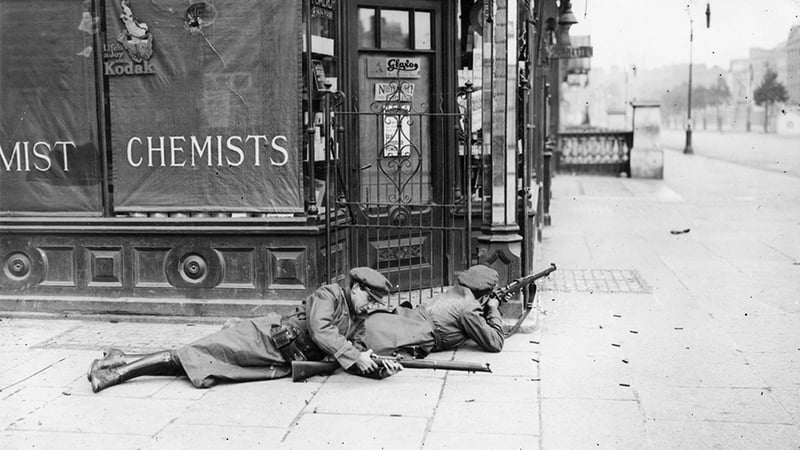

‘Terror meets terror’

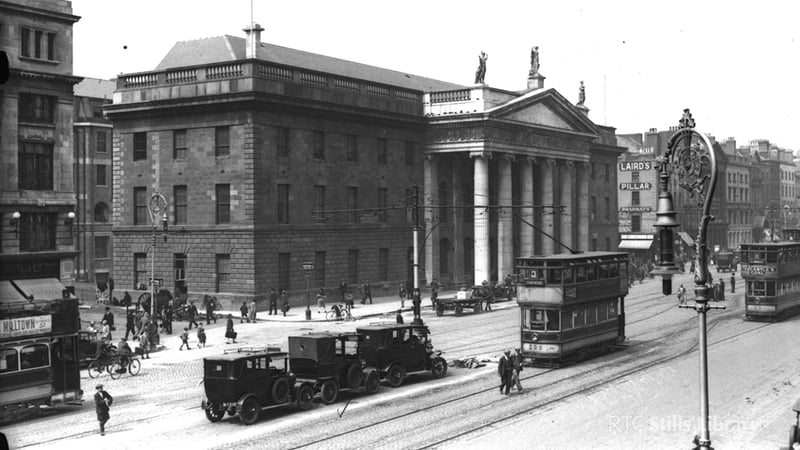

Shortly after the attack on the Four Courts he insisted on the republicans’ unconditional surrender, and subsequent remarks indicate his unchanging determination: ‘we will not suffer a section to dictate by armed force to the Nation’; ‘Irish democracy is too well-founded to tolerate the imposition of a new political aristocracy’; ‘we will give them a damn good hammering’; and if it proved necessary, the government would ‘exterminate ten thousand Republicans’.

Most dramatically of all, when a Dáil deputy was murdered and four republican prisoners were executed in retaliation, he announced that ‘terror meets terror’. This action was illegal, and many people regarded it as immoral, but it showed clearly that the government was prepared to take drastic measures to win the war.

'Not enough executions'

In March 1923 Cosgrave complained that there were not enough executions. Despite his devout Catholicism, he rejected interventions from the archbishops of Armagh and Dublin, and he spurned attempts at mediation – including one by the Vatican. (The pope was informed that his emissary’s actions encouraged the forces of disorder and anarchy operating against the government and the people.)

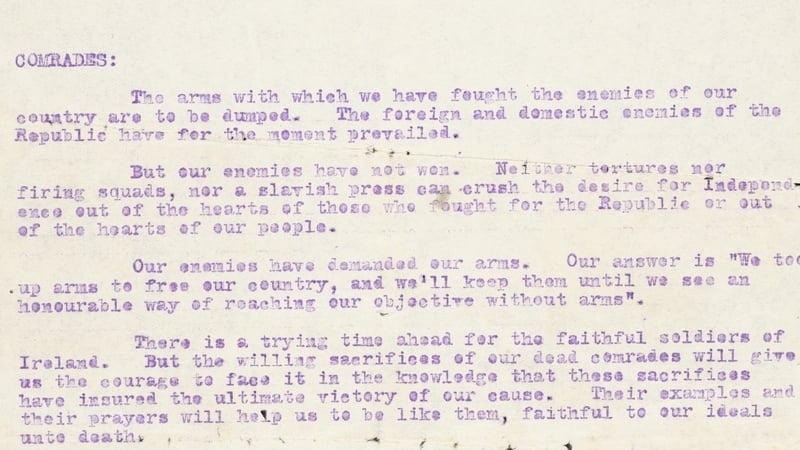

He insisted that the only way to restore peace was for the ‘irregulars’ to lay down their arms, and ultimately they did. It was his colleague Kevin O’Higgins who declared that the government would not accept a draw with a replay in the autumn, but this view reflected fully the spirit of Cosgrave himself and the rest of the cabinet.

Away from the stepping stone?

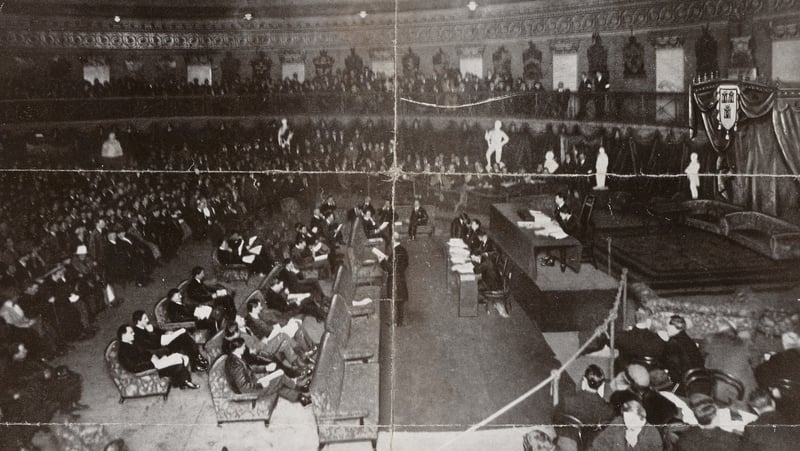

Collins had chosen to fight the war without the distraction of parliamentary criticism, and on several occasions he postponed summoning the newly-elected Third Dáil. But once Cosgrave succeeded him this policy was reversed abruptly, and from early September onwards the government was answerable to criticism in the Dáil (although it was a parliament from which the principal opposition party had chosen to abstain).

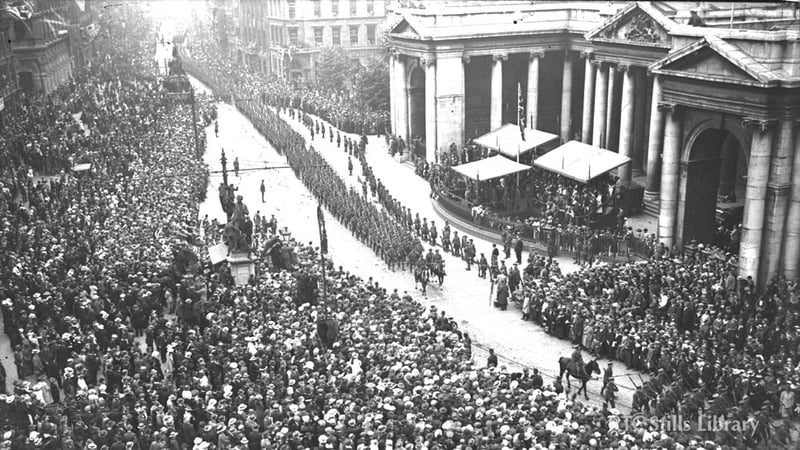

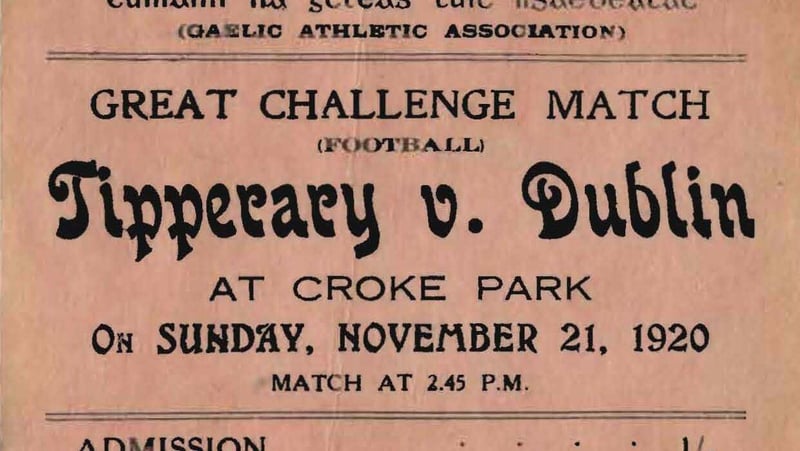

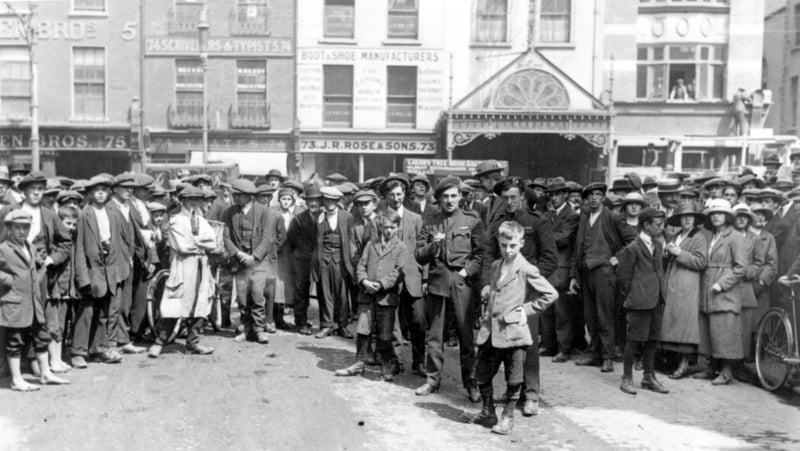

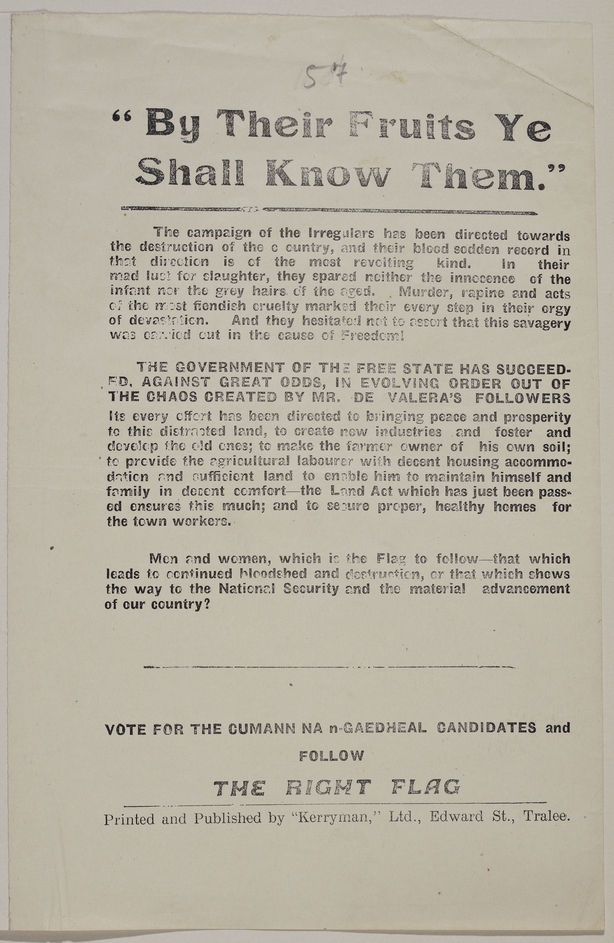

In the war both sides resorted to atrocities, and savage actions by National Army troops in Kerry soon became notorious. But the government remained confident that the public supported the Treaty, as was shown decisively in the general election of June 1922, and it believed that it was implementing the people’s wishes.

Just as many opponents of the Treaty were committed to the ideal of an abstract Republic, so the cabinet viewed itself as the enforcer of democracy. However, its defence of the Treaty during the Civil War seems to have pushed its members into upholding the settlement in all its details, rather than using it as a ‘stepping stone’.

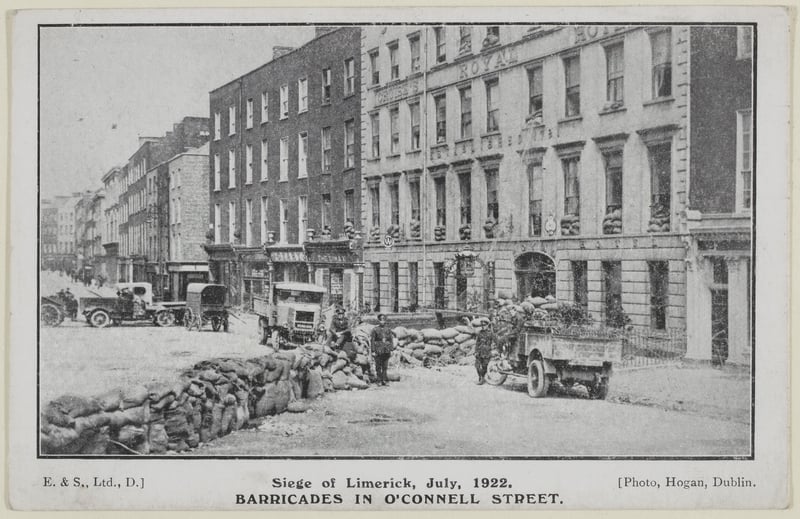

Winning the war

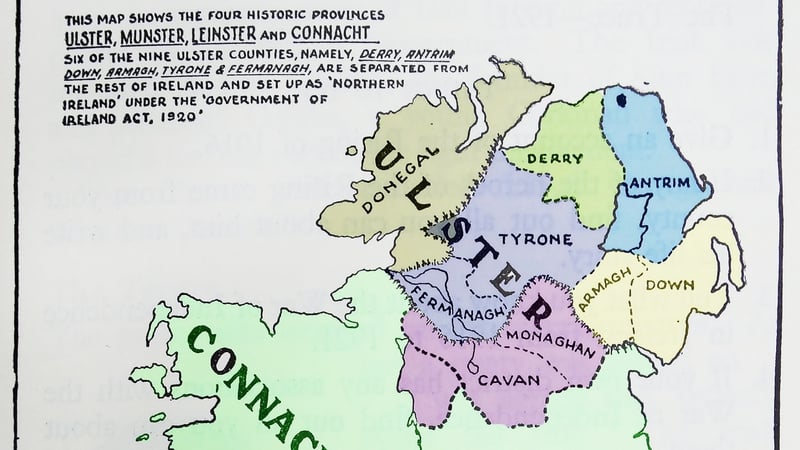

Cosgrave and his colleagues operated under stressful conditions, living for months under siege, and holding as many as twenty-five cabinet meetings in March 1923. They were preoccupied with numerous other matters, such as drafting a new constitution, crushing industrial unrest, making preparations for the boundary commission, establishing civilian control over the army, restructuring government departments, negotiating with the British, and securing admission to the League of Nations. But winning the war came before everything else.

In the words of J. J. Lee, Cosgrave learned,

‘however reluctantly, the fundamental lesson on which the survival of civilised public life depends: that moderates must be prepared, in the last resort, to kill in defence of moderation.’

Some moderates and liberals have been reluctant to abandon compromise or to have blood on their hands, but Cosgrave was not among them. More prisoners were executed under the Free State government in 1922 and 1923 than under British administrations between 1916 and 1921. But they were killed to ensure the preservation of majority rule, and after the war finally came to an end the government was – gradually – prepared to show tolerance and magnanimity.

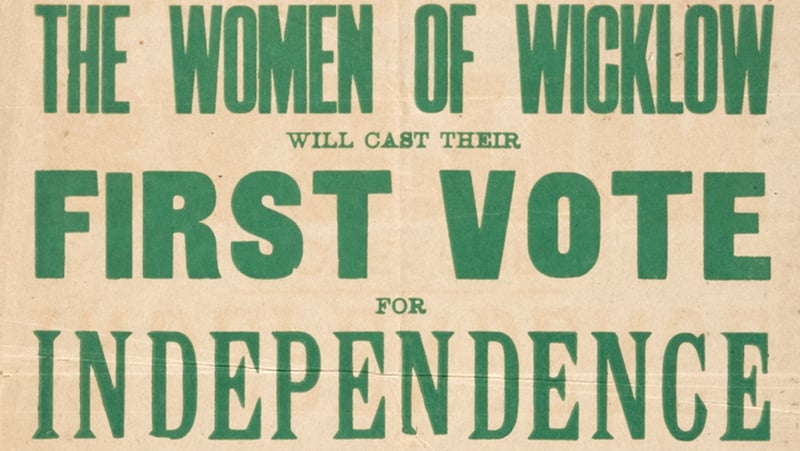

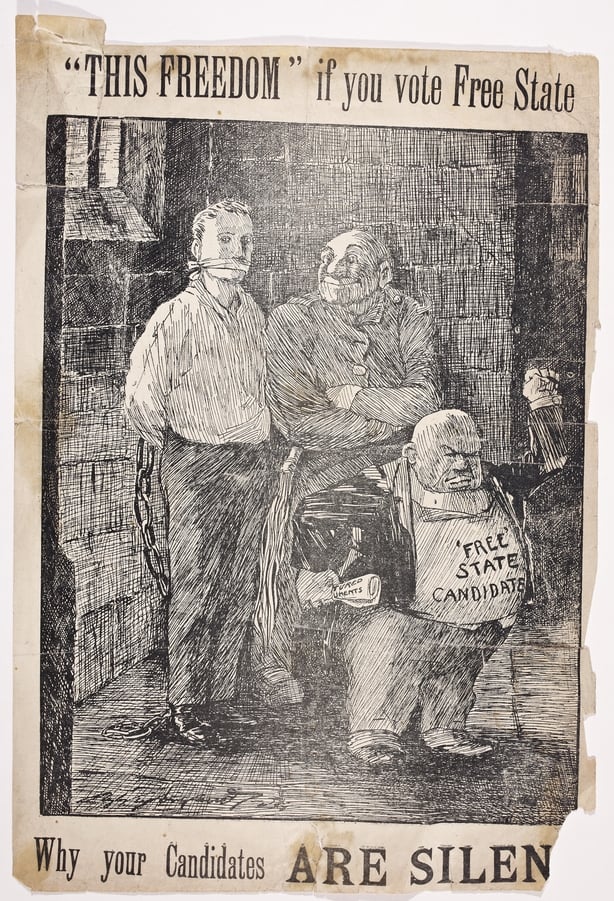

Putting it to the vote

In the election of August 1923 many republican candidates were still in jail, but many of them were elected to a Dáil whose authority they rejected. The overall result was far more favourable to opponents of the Treaty than had been expected, and it proved to the more realistic among them that there was a ‘political path’ to achieve their objectives. Subsequently Cosgrave's government compelled them to act in their own interests and enter the Dáil. This pattern of politicising the republicans was consolidated by the peaceful transfer of power from Cumann na nGaedheal to Fianna Fáil in 1932.

Cosgrave had been firm, even harsh, in fighting a war to ensure the triumph of a government responsible to the electorate, but his commitment to this ideal was genuine. The Free State had been created in large part as the result of military conflict, but it was ruled by authoritarian civilians who believed in, fought for, and practiced democracy.

This article is part of the Civil War project coordinated by UCC and based on The Atlas of the Irish Revolution edited by John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy and John Borgonovo. Its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.