The Discovery of Modern Antipsychotics

How a surgeon and a failed drug for malaria changed the treatment of psychoses.

Posted March 8, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Until the 1950s, the practice of psychiatry, and the treatments for psychoses, were very different from today. Perhaps two-thirds of psychiatrists worked in large facilities whose function was as custodial as it was therapeutic. Psychiatrists themselves were distanced from the mainstream of physicians, not only by the walls of these asylums, but also by the dominance of a psychoanalytic framework emphasizing hypothetical structures and energies in the mind which seemed alien to the practicing doctor.

Although most institutionalized patients were taking medicines, largely to control behavior, there was a sense that they were not central to their care; often drugs weren’t even mentioned in the chart, but rather were listed on supplementary ‘medicine cards.’ Those that were used included opiates, drugs such as chloral hydrate and paraldehyde with roots in the nineteenth century, and later the barbiturates, which had been available since 1904, as well as amphetamines since the 1930s. Hospitalized patients were also exposed to a variety of relatively ineffective and often unpalatable physical therapies. All of this changed in the early 1950s, beginning with the work of an observant French naval surgeon in North Africa.

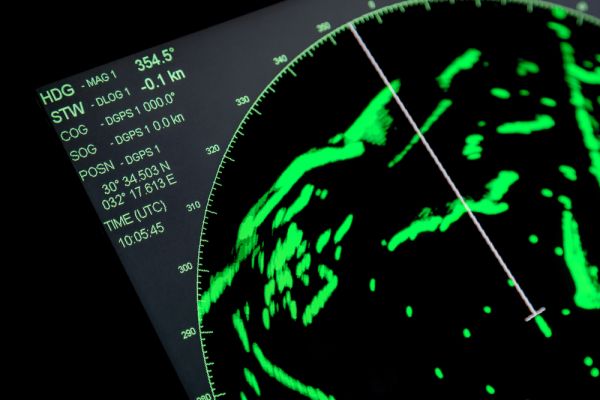

Bizerte is a small Tunisian town on the Mediterranean, and the most northern location in Africa. Its deepwater harbor was recognized as far back as 1100 BC by the Phoenicians, and for centuries thereafter, indeed to the present time, it has been utilized by seagoing nations. In the late 1940s it was the home of a French naval base. At first glance, the surgical unit of the Bizerte Naval Hospital at Sidi Abdallah might seem an unlikely place to revolutionize modern psychiatric treatment, which as it turns out is exactly what happened. Stationed there was a surgeon named Henri Laborit (1914-1995), born in French Indochina as the son of a colonial physician, and a combat veteran who had been aboard the destroyer Siroco at the evacuation of Dunkirk. He had gone to the French School of Naval Medicine and developed an interest in preventing deaths from shock during and after surgery.

Laborit developed a theory that the catastrophic decline in blood pressure and circulation during shock was made worse, not better, by some aspects of the body’s response to stress. He was interested in particular by changes in the autonomic nervous system, and the role of histamine, one of the natural substances released during surgery which increases capillary permeability and lowers blood pressure. It seemed possible, then, that antihistamines might modulate the stress response. He also recognized that anesthetics including chloroform and ether interact with stress to induce shock and reasoned that if medicines could be found to lower the dose of anesthetics needed, there would be a corresponding decrease in risk.

In pursuing this goal, Laborit became interested in promethazine, an antihistamine derivative in a class of medicines known as phenothiazines, which seemed to make patients more relaxed before surgery and aided in anesthesia. Returning to Paris in 1950, he asked the pharmaceutical company Rhone-Poulenc for similar compounds. As it happened, one of their chemists, Paul Charpentier, had been testing chlorpromazine, a derivative of promazine as a treatment for malaria. It was largely ineffective for this purpose, but he noted that it had significant antihistaminic properties, and sent it along. Laborit and his colleagues found that chlorpromazine seemed to produce a state of relaxation and indifference without losing consciousness, and it soon became part of an ‘anesthetic cocktail’ which lowered body temperature and helped decrease the dose of anesthetic drugs.

At that time in Europe, one major way in which doctors tried to control agitation in psychotic patients was by placing them in ice packs. Laborit, recognizing that chlorpromazine both quieted surgical patients and lowered their temperature, thought that it thus might be a useful psychiatric medicine. He convinced his colleagues at Val de Grace, a military hospital in Paris, to give chlorpromazine to an agitated 24-year-old manic patient, and a remarkable quieting effect was soon evident. After 20 days of repeated treatments with chlorpromazine as well as barbiturates, he was able to leave the hospital.

Although this dramatic finding was reported at a psychiatric meeting in 1952, there was a great deal of resistance by the medical establishment to using drugs for psychosis. At the time, the mainline treatments were sedatives, shock therapy and psychotherapy. Luckily, one of Laborit’s anesthetist colleagues contacted his brother-in-law, Pierre Deniker, a psychiatrist at the large academic Saint Anne Hospital. Deniker and his clinic director Jean Delay tried chlorpromazine, alone and in combination with ice packs, on a group of primarily manic patients. It soon became clear that the cooling aspect was not necessary, but that the drug itself, without needing additional medicine ‘cocktails’ or ice packs, rapidly quieted agitated manic or psychotic patients.

Chlorpromazine was released as a prescription drug in France under the name Largactil (‘large in action’) in 1952, and ultimately produced a revolution in psychiatric treatment. As the next few years went by, reports came in describing improvements in psychoses, and reductions in violence, in hospitals in Europe, the U.S., and Canada. Thousands of patients, once longtime residents of huge psychiatric facilities, were now able to be discharged. By one estimate, in 1953 there were 560,000 patients in American mental hospitals, declining to 193,000 by 1975. Though new kinds of problems appeared, notably the lack of preparation of communities to accept this large inflow, there was a new optimism that medicines might be found for treating psychotic illnesses. Though slightly later than the rediscovery of lithium as a treatment for mania in 1949, chlorpromazine came to the market and was widely accepted sooner, in effect creating the field of modern psychopharmacology.

As for Laborit, in 1958 he founded a laboratory in Boucicaut Hospital in Paris, funded primarily from his drug patents, and indeed virtually all his work was done outside traditional university settings. He went on to discover minaprine, an MAOI antidepressant, as well as the sedative clomethiazole, and wrote extensively about the biological underpinnings of social problems such as aggression. He believed that the best work came from questioning widely held views, an approach which cost him popularity in the traditional medical establishment, but which served him well in a remarkable career.

This article is adapted from The Curious History of Medicines in Psychiatry by Wallace B. Mendelson.

![By Piyush Ikhar (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://cdn2.psychologytoday.com/assets/styles/manual_crop_3_2_600x400/public/field_blog_entry_images/2017-11/long_road_journey.jpg?itok=_nmoZApR)