The good news for the producers of Thirteen Lives: There’s a built-in audience for the story of the 2018 Tham Luang Nang Non rescue, in which an international effort retrieved 12 members of a Thai junior football team and their assistant coach from a huge cave system where they had become stranded by the early arrival of the monsoon. The bad news: The story was covered so exhaustively at the time that much of the core audience is already familiar with all the details and will notice any fudging for dramatic effect. Director Ron Howard’s previous movie about a high-pressure, life-or-death problem in an extreme environment, Apollo 13, also dramatized a well-known story, but it had the advantage of many details previously remaining classified and so unknown to the public. Howard uses the same approach in both films, breaking down one big crisis into several smaller technical challenges, each one of which has the potential to result in disaster. His heroes thus stay rooted in facts, leaving the audience to feel all the emotions that the heroes can’t afford to be distracted by. Below, we sort out where the film sticks to these facts and where it departs.

Was One Member of the Team Really an Undocumented Immigrant?

In the film, the mother of one of the boys tells the assistant to the area’s governor, Narongsak Osatanakorn (Sahajak Boonthanakit), that her family is from Myanmar and so don’t have any official ID cards. As a result, she is worried that her son (Chai, the youngest of the group) won’t be brought out. She is reassured this won’t make any difference.

In fact, not one but three of the boys were “stateless”, as was the assistant coach, Ekkapol Chantawong (Teeradon Supapunpinyo). Stateless people are Thailand’s equivalent of undocumented migrants, unable to vote, buy land, work legally, or travel freely (which meant the stateless boys on the team couldn’t travel outside their home province of Chiang Rai to matches). However, although the Guardian reported all three of the boys were born in Thailand, the Associated Press said that Adul, the lone English speaker among the boys, had been sent by his parents in Myanmar to Thailand to get a better education. The confusion may arise from the fact that all four were from the ethnic minority hill tribes that populate both sides of the porous border in the notorious Golden Triangle, a hotbed of drug smuggling, between Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos, where Thai authorities estimate the “stateless” population with no documented nationality may be as high as three million.

Did the Coach Really Get the Boys to Meditate?

When British rescue divers reach the boys on a supply run, they are surprised to find coach Ekkapol Chantawong leading the team in a meditation session.

Coach “Ek” did indeed use mediation to help the boys ward off fear and despair. According to public radio program The World, he was “exalted” by the Thai media and public for “teaching the boys meditation techniques, fortifying their minds against panic and conserving their energy,” noting that “In a deeply Buddhist nation, this was widely seen as a powerful affirmation of meditation’s potential.” Chantawong’s luster was only burnished when the team emerged from the cave and it was revealed that he had given most of his rations to the boys, as well as insisting on being the last one rescued. These actions may have reflected his growing up in a Buddhist temple, where he lived after losing his parents at age 10. (Temples in Thailand are known for sheltering orphans.) He became a novice monk but left to care for his sick grandmother, dividing his time between maintaining the nearby monastery and training the junior team.

How Many Rescuers Were There Anyway?

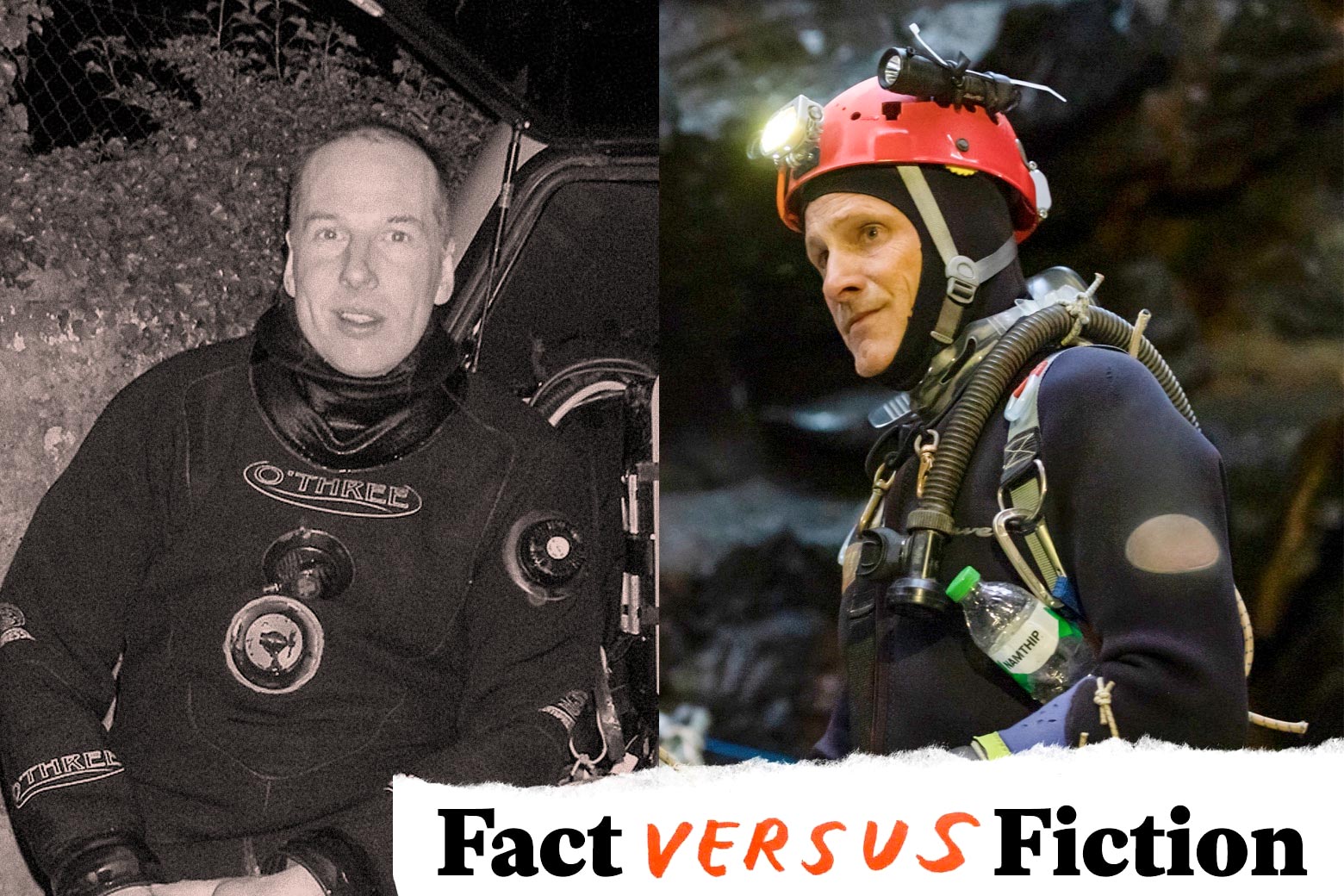

The film depicts about 20 Thai Navy SEALS beginning the rescue operation, but, trained for open water diving and not work in narrow cave tunnels, they can only get about halfway down the tunnel network to Cavern 3. Vernon Unsworth (Lewis Fitz-Gerald), a British caver and expat who is very familiar with the Tham Luang system and has mapped out the tunnel network, suggests bringing in two divers from Britain, world-leading experts with 30 years’ experience in cave rescue: John Volanthen (Colin Farrell) and Richard Stanton (Viggo Mortensen). The SEALS are initially disparaging about the “old men,” but after the two Brits, having grudgingly been allowed to act as “scouts,” manage to get to Cavern 9, where they find the boys alive, the SEALS start to collaborate. Two more British divers and an Australian diver-cum-anesthesiologist, Richard “Harry” Harris (Joel Edgerton), join the team. The actual rescue operation is carried out by these five, assisted by four Thai SEALS and a Navy doctor who have remained with the boys. They bring the “packages,” anesthetized boys in wetsuits and scuba gear on light stretchers with hands and feet restrained, to a staging area in Cavern 3, where the stretchers are guided through the rest of the network to the cave entrance by a team of Thai SEALS and divers.

In actuality, before the British experts arrived, some 110 Thai SEALS were joined by trained European divers from countries including Belgium, France, Ukraine, and Finland, expats who usually ran dive shops on Thailand’s coastal islands. All worked 12 to 14 hours a day for the next four days, creeping forward a meter at a time in total darkness, but they couldn’t get past Cavern 3 due to rising water from the ongoing rain. The two British experts were indeed the first to navigate the difficult narrow tunnels past Cavern 3 and find the boys alive in Cavern 9, and they did bring on two more British divers plus Harris. However, possibly in the name of not overwhelming the audience with more characters than they can possibly keep track of, the film has omitted from the core team another Australian and another lead diver, Jim Warny from Ireland, who joined on the final day of the rescue. (In Warny’s case, it could also be that he opted to star as himself in a separate movie based on the rescue.)

The film’s version of the rescue itself shows only the four British cave dive experts guiding each unconscious boy (one diver per boy) between Caverns 9 and 3 over the course of three days. However, each “package” was actually escorted out by two divers each. According to the New York Times, during the first two days of the rescue, 13 foreign divers (including an American Air Force rescue specialist) and five Thai divers brought out four boys at a time. Also not shown are the 90 Thai divers and the foreign dive shop owners who were stationed along the route to perform medical check-ups and resupply air-tanks for the main divers, and the team who installed the oxygen tanks, cables, lighting system, communication devices, and the water drainage pipes and pumping system used to drain water from the tunnels.

Once a boy and his British guide reach Cavern 3, the film shows the unconscious “package” being handed over to a couple of dozen anonymous figures for the rest of the journey out of the cave before the action switches back to the tunnels. In fact, hundreds of rescuers formed a ‘daisy chain’ to slide, carry, and even zipline the boys on stretchers over a complex network of pulleys previously installed by rock-climbers (also not shown). Some stretchers were placed on an impromptu slide made of hoses installed to pump out water. If this sounds relatively easy, much of the network from Chamber 3 to the cave entrance was still partially submerged, and rescuers had to transport the boys over slippery rocks and through muddy water for hours.

The Makeshift Town Outside the Caves

Finally, the film shows a crowded, chaotic, temporary community springing up at the cave entrance of about 100 people composed of food sellers, equipment maintainers, medics, parents, and military support staff. In fact, Ivan Karadzic, a former Danish insurance salesman turned technical dive instructor, told National Geographic that he’d heard there were more than 7,000 volunteers on the mountain whose tasks ranged from cooking 20,000 meals a day (free to the rescue teams) to doing laundry or making airport runs. Additionally, there were hundreds of rescue workers, representatives from more than 100 governmental agencies, 900 police officers, 2,000 members of the Thai military, and overseas military teams accompanying search-and-rescue equipment. And 1,500 journalists.

Did One of the Rescue Divers Get Lost on the Way Out?

The tunnels are so murky that even with headlamps, the only way the rescue divers can find their way out and not get lost in the cave network is by keeping hold of a guide rope installed before the boys are swum out from Cavern 9. One of the British expert divers, Chris Jewell, loses his grip on the guideline as he’s bringing out his “package” and, disoriented and not sure he’s still in the escape tunnel, puts his boy on a ledge in a cavern, removes the boy’s scuba mask, and wraps him in a foil blanket while waiting to see if another diver turns up. Harris, one of the last out, does, and takes Jewell’s boy the rest of the way to Cavern 3.

This did happen, but it wasn’t only Jewell who lost hold of the guideline. Lead diver John Volanthen managed to swim two boys out, but on the third, his “package” became tangled in telephone wires that had been laid down before the cave flooded, and Volanthen had to cut the unconscious boy loose before he could go any farther, an episode omitted from the film. Meanwhile, Karadzic, the Danish support diver, lost the guideline when the strap of his borrowed caving helmet began to choke him and he couldn’t unlatch it.

Did Local Farmers Really Flood Their Rice Paddies to Help the Boys?

As the film makes clear, the rescue efforts underground were only part of the story. With the attempt to reach the boys suspended because of the constantly-rising water level, a Thai-American water engineer points out that unless the water pouring in from above is diverted, the divers will never be able to get in. The governor gives him permission to set up a system to drain the water from the top and divert it onto the rice paddies below. This will ruin the rice harvest of the poor farmers who own the paddies. Still, the farmers not only agree but help build the system.

It was in fact the Thai military who called in Thanet Natisri (Nophand Boonyai), a Thai restaurant owner and self-taught groundwater storage expert from Marion, Illinois who happened to be working on a project in Thailand building wells for farmers. After the military asked for his help in controlling the amount of water entering the cave, Natisri found himself coordinating a team that included 270 Thai Army soldiers, 150 members of a Thai rescue volunteer organization, and about 20-40 local farmers, who sacrificed their harvest to the rescue effort.

“We had to come up with a plan to reduce the water. I was in a difficult position coordinating everyone and the daily plan,” Thanet told his hometown paper. “Nobody wanted to be in this position. Nobody wanted to be responsible for the plan. If something happened to one of the kids, I would feel guilty all of my life.”

While Natisri’s team was blocking sinkholes outside the cave, inside the cave a team of hydrologists and drillers pumped out groundwater and diverted streams, removing some 420,000 gallons per hour from the cave.

What About Elon Musk?

Neither Musk, the kid-sized submarine he proposed sending into the tunnels, nor the fact that he facetiously called one of the rescuers a “pedo guy” gets a mention.