In September 1969, the bass player and artist Klaus Voormann, who had recently left Manfred Mann, received a phone call from John Lennon. There was nothing unusual in that. Voormann had known the Beatles for nine years and was part of the band’s tight inner circle. It was Voormann’s own band, Paddy, Klaus and Gibson, that Lennon and George Harrison had attempted to go and see live on the night they were famously dosed with LSD at a dinner party. Ringo Starr was already at the gig and was noisily confronted by his lysergically altered bandmates claiming that the venue’s lift was on fire. A year later, he had designed the Grammy award-winning cover of Revolver.

The issue was more what Lennon wanted him to do. Lennon had whimsically agreed to perform live at a rock’n’roll revival festival in Toronto at two days’ notice and was trying to cobble together backing musicians to play as the Plastic Ono Band. Eric Clapton had agreed to play guitar, but Voormann took more convincing, on the not-unreasonable grounds that headlining a festival with a new band who hadn’t rehearsed didn’t seem like one of Lennon’s more inspired ideas.

“John said, ‘Oh, we’ll rehearse on the plane.’ So there we were, sitting in the last row, next to the jets, and me playing an electric bass with no amplifier,” he says, crackling down the phone line from his home in Bavaria. “I couldn’t hear a thing that I was doing. I was more nervous for John than me. I mean, John – the Beatle – suddenly going up on stage with a band that hadn’t rehearsed. It was incredible.”

Moreover, Lennon had elected not just to play a brief set of rock’n’roll covers befitting a festival that also featured Gene Vincent, Little Richard and Bo Diddley, but to cede the microphone to Yoko Ono, who performed two ear-splitting improvisations, one of which lasted more than 12 minutes. “People were just open-mouthed. They are at a rock’n’roll festival with Chuck Berry, and then suddenly this avant garde thing is presented,” he says. “I was up on stage, standing behind Yoko, she’s screaming and shouting and croaking like a dying bird, and I felt ‘this is about the Vietnam war’ – I really saw tanks next to me and bombs falling and dead people, that was the thing she was expressing. But I thought: ‘My God, John must be mad to do this.’ I mean, we were lucky people didn’t throw tomatoes at him.”

Still, he says, there were advantages to Yoko’s brand of live performance. “When you really know it’s that crazy, you don’t think: ‘Oh, what am I going to do on stage?’ You’re not scared, you just do it, it’s easy. I mean,” he laughs, “you can make all the mistakes you want – it doesn’t matter. It’s punk.”

Perhaps Voormann should have been used to unexpected situations involving the Beatles. He was an art student with a love of jazz, Nouvelle Vague cinema and a penchant for dressing like a young French intellectual when he first encountered them in 1960. After storming out of his girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr’s home during a row, he found himself outside a particularly seedy club in Hamburg’s St Pauli district, transfixed by the racket emanating from within. He had heard rock’n’roll before, although his tastes tended more towards Miles Davis, but he had never heard it played live, and certainly not with the ragged energy of nascent Beatles. Nevertheless, he says, he was torn about entering the club, which was visibly “dangerous”.

It’s easy to romanticise the Beatles’ years in Hamburg – Birth of a Legend, as one live album recorded there put it – but Voormann says the reality was genuinely frightening. “It was the dirty part of Hamburg, hookers and pimps running around. There were knife fights in the clubs. I thought: ‘Oh Christ, I’m not going in there.’ But eventually, I pulled myself together and did go in.”

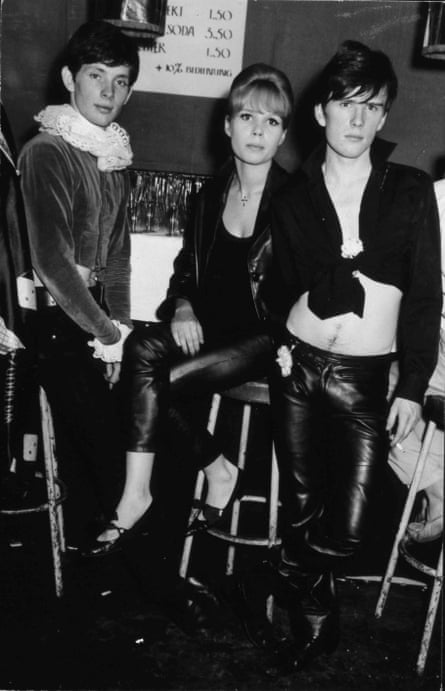

He later returned with Kirchherr and their friend Jürgen Vollmer: they looked so out of place that the waiters took pity on them and “took care of us if there was a fight going on”. After initially being rebuffed by Lennon, they struck up a friendship with the band, aided by the fact that Kirchherr invited them to her parents’ house so they could have a bath: the band’s living conditions were so squalid that they were forced to wash and shave using water from the club’s urinals.

Kirchherr began a relationship with the band’s bassist Stuart Sutcliffe and, most famously, the band adopted the same appearance as their new friends, abandoning their leathers and quiffs in favour of combing their hair forward: the mop-top. Lennon dubbed the Germans “the exis”, short for existentialists, apparently incorrectly.

“Maybe we looked like those French artists, but we were not existentialists,” says Voormann. “We weren’t political at all. We took them to the pictures so they could see these films we loved – Jean Cocteau, Louis Malle – and we went to exhibitions and turned them on to French art.”

One night at the Kaiserkeller, Sutcliffe handed Voormann his bass guitar and told him to go on stage instead of him. He was a guitarist, but had no experience with the instrument. The first time he played bass was on stage with the Beatles, which seems faintly incredible, even if Voormann says the reality was less thrilling. “Well, you see, that sounds so fantastic,” he says. “But it was a rock’n’roll band, they were playing in the middle of the night, Stuart was wanting to have a break so he could cuddle with Astrid on the sofa. So I sort of played along on a Fats Domino number.”

He says he always knew the Beatles were going to be big – “I couldn’t wait for them to be famous” – but clearly had no idea of the scale of what was about to happen. He came to England in 1963, by which time Sutcliffe was dead – he’d left the band to stay with Kirchherr in Hamburg before suffering a brain haemorrhage, aged 21 – and Beatlemania was in full swing. Voormann shared a flat with Harrison and Starr, struck by the sense of how pleased they seemed to see an old face amid the ensuing madness.

Later, he watched the band slowly disintegrate: “Those 10 years were more than enough. Ringo would have stayed with the band, he loved everybody, but the rest, there was lots of anger, fights: they couldn’t have done it any longer because they were all in completely different directions. Abbey Road, it’s a beautiful LP, but … from a feeling point of view it wasn’t right to do it. They had to do it because they had obligations to the record company. But they did it really professional and fantastic, and that’s what makes a good band, you know?”

Indeed, at one point during the band’s split, a persistent – and apparently completely unfounded – rumour suggested Voormann was going to join the Beatles, or rather, that Lennon, Harrison and Starr were going to form a new band called the Ladders, with Voormann replacing Paul McCartney. Instead, he played on all three’s solo albums throughout the 70s. He has a particular affection for 1970s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band: “Everything done in two takes, no fussing about, so raw and fresh and direct … Nobody ever told me what to play. I always played what I felt would suit the spirit of the song or the lyrics.

“He always did that, on all the sessions I did: Imagine, Walls and Bridges, Rock ’n’ Roll. But let’s say if I ever played a wrong note or played shit, he would have told me. The same with the cover of Revolver: if I hadn’t come up with a good idea, then I wouldn’t have got the job – ‘Sorry, Klaus …’”

Voormann subsequently became an in-demand session musician – it’s him playing the famous bass intro on Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain and playing on Lou Reed’s Perfect Day, the latter a session he remembers largely for the amount of camp badinage passing between Reed and co-producer David Bowie. He spent the 70s in Los Angeles, returning to Germany at the end of the decade.

Before he left the US, he visited Lennon at home in New York, and found him in househusband mode, boiling rice to make sushi and expounding on the joy of no longer having a record deal or the pressure that came with it. But he was struck by an odd sense of foreboding.

“I went with my son, Otto, who was the same age as Sean. We went for a walk in Central Park and John had Sean in a backpack. We walked out through the basement, where the garage was, and I thought: ‘Oh Christ, this is scary. All those really crazy people in New York and there’s John Lennon just walking around with no bodyguards or anything!’ I was scared for him: ‘My God, if that’s what he’s doing every day … I don’t know.’”

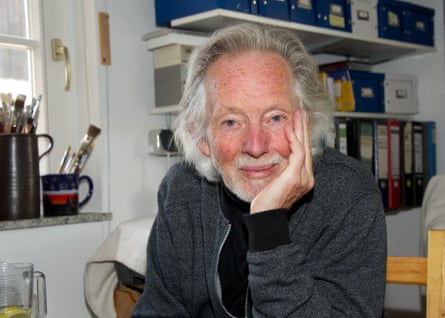

Back in Germany, Voormann worked with Trio, the post-punk band famed for the 1982 hit Da Da Da, but eventually gave up music to concentrate on writing and art. He designed the covers for the Beatles’ Anthology compilations, and in recent years, has published books and a graphic novel about his time with the Beatles and worked with Liam Gallagher on the packaging of his solo debut As You Were. At 82, he has contributed a series of drawings to a new book about Lennon’s early solo career, and the making of the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album – one of them depicts the chaotic in-flight rehearsal for the Toronto rock festival, the musicians crammed together at the rear of the plane.

These days, he says, he no longer even owns a bass guitar. “To play bass all by yourself is a bit silly,” he says: who could he possibly play with? “I was spoiled,” he chuckles.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion