Produced by the Office of Marketing and Communications

The Dawn of Election Night Computer Forecasting

Journalism Professor’s New Book Details How ‘Mechanical Brains’ Paved Path for Modern-Day Coverage

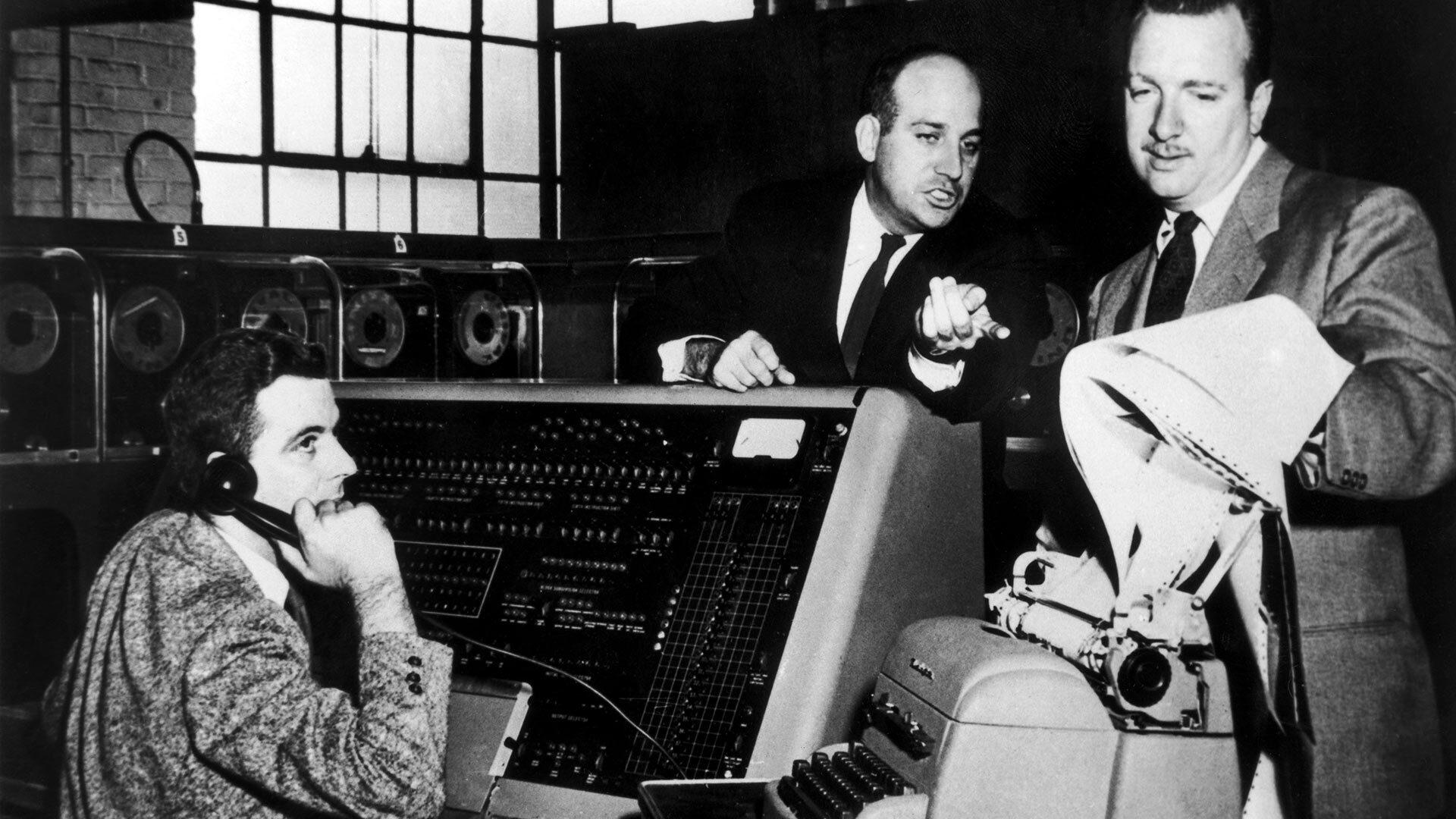

Famed CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite, right, with the UNIVAC machine that would be used on election night in 1952. In a new book, journalism Professor Ira Chinoy details how TV networks used computers on air for the first time.

Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

On election night in 1916, instead of being glued to 24-hour news coverage or doomscrolling social media, you could find out election results by going to see a burlesque show where results would be announced every half hour. Or in 1928 you could join the crowd waiting for returns on a “zipper” of flashing letters and numbers circling The New York Times building. Or way back in 1896, you could listen for a steamship whistle blasting out coded sounds.

So when computers became the latest technology—clunky and room-sized as some were post-World War II—it’s no surprise that television networks, then also in their infancy, saw an opportunity.

University of Maryland journalism Associate Professor Ira Chinoy covers that halting start in a new book coming out May 1: "Predicting the Winner: The Untold Story of Election Night 1952 and the Dawn of Computer Forecasting.”

“Election night has been a venue for rolling out new technology for more than a century,” he said. When it comes to computers, “there’s a cartoon-like version of the story that appears every four years: CBS used a big UNIVAC (computer), didn’t believe the results, the machine got it right and the humans got it wrong. Dog bites man, machine makes monkey out of man.”

Chinoy, who started doing computer-assisted reporting in the 1980s “when it was considered a freakish thing,” suspected there was more to that story. He began digging for his dissertation at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism in the early 2000s. Now, after two decades of on-and-off research, taking him across the country and deep into dozens of archives, he’s publishing the first comprehensive look at how journalists first used computer forecasting.

He shares why 1952 was a make-or-break moment for news organizations, how a UMD alum played a role in one of the “mechanical brains” that debuted that night and why media innovation is again needed today.

Making Up for 1948: “Dewey Defeats Truman”

“There was a crisis of credibility because news organizations had gotten it upside down in 1948,” reporting that President Harry Truman had lost to New York Gov. Thomas E. Dewey—an image immortalized by Truman holding up the front page of The Chicago Daily Tribune with the infamously premature headline, grinning widely.

The debut of television election coverage that year simply brought radio commentary to the screen. “It was a complete flop in terms of visual display of election returns,” said Chinoy. “News managers recognized before the next election that if they hooked up with computer companies, maybe they’d have an edge.”

Two Machines, One Result

Two TV networks deployed computers in 1952. CBS had the UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer), a massive machine that couldn’t be moved from its facility in Philadelphia. NBC touted the Monrobot, developed in part by recent UMD engineering grad Richard LaManna ’51, which was smaller and brought into the studio in New York. Both networks tried to dress up their “monster of electronic thought” in different ways. On the CBS set in Manhattan, a dummy UNIVAC console was hooked up to something like a Christmas-tree light timer so its display would blink. NBC went for sex appeal, advertising a “beautiful woman with a Ph.D.” who would translate data from the Monrobot.

Ultimately, the networks relied on their computers only sparingly that night. “They were not going to put all their eggs in the computer basket,” Chinoy said. “They had pundits, pollsters, political party people and correspondents—they weren’t being crazy with the risk.”

In his minute-by-minute recap of the coverage on NBC and CBS, he discovered that the traditional dog-bites-man narrative wasn’t quite right. Early in the evening, reports showed that Dwight D. Eisenhower was clearly in the lead. But the UNIVAC team was so surprised by the computer’s prediction of a landslide that they delayed sending it to CBS. After being burned four years earlier, TV anchors were also reluctant to call an Eisenhower sweep too quickly. Eisenhower went on to defeat Democratic Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson II handily.

Can Tech Help Rebuild Trust in Media?

“We can’t imagine election night now without computer projections,” said Chinoy. But at the same time, there’s been a “decline in trust in news that’s been going on for more than a generation” and desperately needs repair–especially in light of the chaotic events on and after election night 2020.

For some, artificial intelligence might be the answer. As the accuracy of polls is harder to achieve with fewer landlines to contact potential respondents, news organizations may explore other methods of predicting results.

But any tech needs to go hand in hand with a deeper examination of what caused Americans to become so susceptible to false information, Chinoy said, from shoring up local news (historically more trusted than national organizations) to examining the psychology behind cycles of misinformation and grievance.

“We’ve got to dig in as a news industry and a society. It’s all hands on deck. We’ve got to do this if we’re going to save democracy,” he said.

Maryland Today is produced by the Office of Marketing and Communications for the University of Maryland community on weekdays during the academic year, except for university holidays.

Faculty, staff and students receive the daily Maryland Today e-newsletter. To be added to the subscription list, sign up here:

Subscribe