Top Quotes: “Emotional Intelligence” — Daniel Goleman

Introduction

“Anyone can become angry — that is easy. But to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way — that is not easy.” — Aristotle

“I was heading back to a hotel, and as I stepped onto a bus up Madison Ave I was startled by the driver, a middle-aged black man with an enthusiastic smile, who welcomed me with a friendly, ‘Hi! How you doing?’ as I got on, a greeting he proffered to everyone else who entered as the bus wormed through the thick midtown traffic. Each passenger was as startled as I, and, locked into the morose mood of the day, few returned his greeting.

But as the bus crawled through the gridlock, a slow, rather magical transformation occurred. The driver gave a running monologue for our benefit, a lively commentary on the passing scene around us: there was a terrific sale at that store, a wonderful exhibit at this museum, did you hear about the new movie that just opened at that cinema down the block? His delight in the rich possibilities the city offered was infectious. By the time people got off the bus, each in turn had shaken off the sullen shell they’d entered with, and when the driver shouted out a so ‘So long, have a great day!’ each gave a smiling response.

The memory of that encounter has stayed with me for close to 20 years. When I rode that Madison Ave bus, I’d just finished my own doctorate in psych — but there was scant attention paid in the psychology of the day to just how such a transformation could happen. Psychological science knew little or nothing of the mechanics of emotion. And yet, imagining the spreading virus of good feeling that must’ve rippled through the city, starting from passengers on his bus, I saw that this bus driver was an urban peacemaker of sorts, wizardlike in his power to transmute the sullen irritability that seethed in this passengers, to soften and open their hearts a bit.”

“What factors are at play, for example, when people of high IQ flounder and those of modest IQ do surprisingly well? I would argue that the difference quite often lies in the abilities called here emotional intelligence, which include self-control, zeal and persistence, and the ability to motivate oneself. And these skills can be taught to children, giving them a better chance to use whatever intellectual potential the genetic lottery may’ve given them.”

Emotions

“The ability to control impulse is the base of will and character. By the same token, the root of altruism lies in empathy, the ability to read emotions in others; lacking a sense of another’s need or despair, there’s no caring.”

“All emotions are, in essence, impulses to act, the instant plans for handling life that evolution has instilled in us. The very root of the word emotion is motere, the Latin verb ‘to move,’ plus the prefix ‘e-’ to connote ‘move away,’ suggesting that a tendency to act is implicit in every emotion. That emotions lead to actions is most obvious in watching animals or children; it’s only in ‘civilized’ adults we so often find the great anomaly in the animal kingdom, emotions — root impulses to act — divorced from obvious reaction.”

- “With anger blood flows to the hands, making it easier to grasp a weapon or strike at a foe; heart race increases, and a rush of hormones such as adrenaline generates a pulse of energy strong enough for vigorous action.

- With fear blood goes to the large skeletal muscles, such as in the legs, making it easier to flee — and making the face blanche as blood is shunted away from it (creating the feeling that blood ‘runs cold’). At the same time, the body freezes, if only for a moment, perhaps allowing time to gauge whether hiding might be a better reaction. Circuits in the brain’s emotional centers trigger a flood of hormones that put the body on general alert, making it edgy and ready for action, and attention fixates on the threat at hand, the better to evaluate what response to make.

- Among the main biological changes in happiness is an increased activity in a brain center that inhibits negative feelings and fosters an increase in available energy, and a quieting of those that generate worrisome thought. But there’s no particular shift in psych save a quiescence, which makes the body recover more quickly from the biological arousal of upsetting emotions. This configuration offers the body a general rest, as well as readiness and enthusiasm for whatever task is at hand and for striving toward a great variety of goals.

- Love, tender feelings, and sexual satisfaction entail parasympathetic arousal — the physiological opposite of the ‘fight-or-flight’ mobilization shared by fear and anger. The parasympathetic pattern, dubbed the ‘relaxation response,’ is a bodywide set of reactions that generates a general state of calm and contentment, facilitating cooperation.

- The lifting of the eyebrows in surprise allows the taking in of a larger visual sweep and also permits more light to strike the retina. This offers more info about the unexpected event, making it easier to figure out exactly what’s going on and concoct the best plan for action.

- Around the world an expression of disgust looks the same and sends the identical message: something is offensive in taste or smell, or metaphorically so. The facial expression of disgust — the upper lip curled to the side as the nose wrinkles slightly — suggests a primordial attempt, as Darwin observed, to close the nostrils against a noxious odor to spit out a poisonous food.

- A main function for sadness is to help adjust a significant loss, such as the death of someone close or a major disappointment. Sadness brings a drop in energy and enthusiasm for life’s activities, particularly diversions and pleasures, and, as it deepens and approaches depression, slows the body’s metabolism. This introspective withdrawal creates the opportunity to mourn a loss or frustrated hope, grasp its consequences for one’s life, and, as energy returns, plan new beginnings. This loss of energy may well have kept saddened — and vulnerable — early humans close to home, where they were safer.”

“Species that have no neocortex, such as reptiles, lack maternal affection; when their young hatch, the newborns must hide to avoid being cannibalized.”

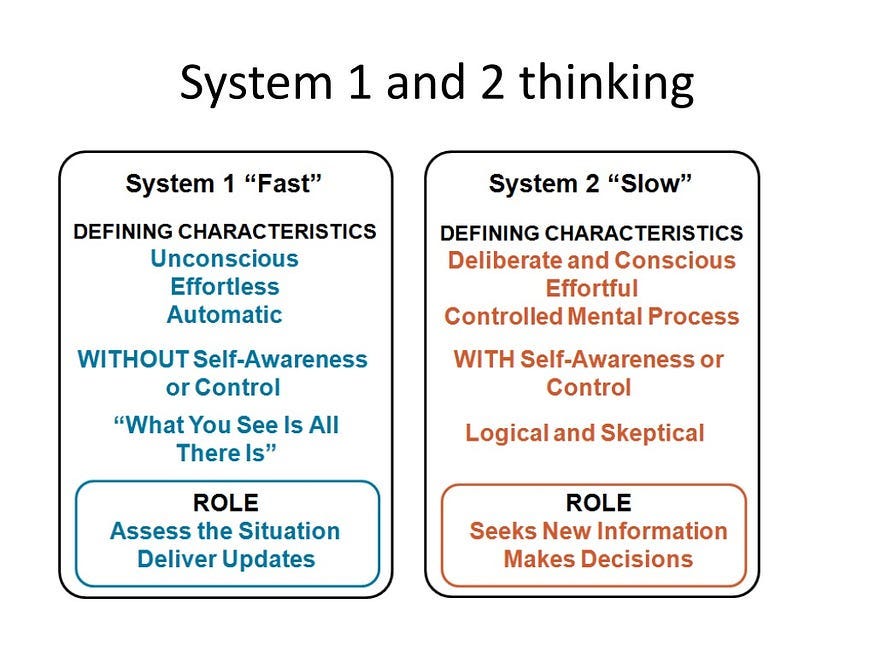

“Emotional explosions are neural hijackings. At those moments, evidence suggests, a center in the limbic brain proclaims an emergency, recruiting the rest of the brain to its urgent agenda. The hijacking occurs in an instant, triggering this reaction crucial moments before the neocortex, the thinking brain, has had a chance to glimpse fully what’s happening, let alone decide if it’s a good idea. The hallmark of such a hijack is that once the moment passes, those so possessed have the sense of not knowing what came over them.”

“It’s in moments such as these — when impulsive feeling overrides the rational — that the newly discovered role for the amygdala is pivotal. Incoming signals from the senses let the amygdala scan every experience for trouble. This puts the amygdala in a powerful post in mental life, something like a psychological sentinel, challenging every situation, every perception, with but one kind of question in mind, the most primitive: ‘Is this something I hate? That hurts me? Something I fear?’ If so — if the moment at hand somehow draws a ‘Yes’ — the amygdala reacts instantaneously, like a neural tripwire, telegraphing a message of crisis to all parts of the brain.”

“Research has shown that sensory signals from eye or eye travel first in the brain to the thalamus, and then — across a single synapse — to the amygdala; a second signal from the thamalus is routed to the neocortex — the thinking brain. This branching allows the amygdala to begin to respond before the neocortex, which mulls info through several levels of brain circuits before it fully perceives and finally initiates its more finely tailored response.”

“‘Anatomically the emotional system can act independently of the neocortex,’ LeDoux told me. ‘Some emotional reactions and emotional memories can be formed without any conscious cognitive participation at all.’ The amygdala can house memories and response repertoires that we enact without quite realizing why we do so because the shortcut from the thalamus to amygdala completely bypasses the neocortex. This bypass seems to allow the amygdala to be a repository for emotional impressions and memories that we’ve never known about in full awareness. LeDoux proposes that it’s the amygdala’s subterranean role in memory that explains, for example, a startling experiment in which people acquired a preference for oddly shaped geometric figures that had been flashed at them so quickly that they had no conscious awareness of having seen them at all!

Other research has shown that in the first few milliseconds of our perceiving something we not only unconsciously comprehend what it is, but decide whether we like it or not; the ‘cognitive unconscious’ presents our awareness with not just the identity of what we see, but an opinion about it. Our emotions have a mind of their own, one which can hold views quite independently of our rational mind.”

“As the repository for emotional memory, the amygdala scans experience, comparing what’s happening now with what happened in the past. Its method of comparison is associative: when one key element of a present situation is similar to the past, it can call it a ‘match’ — which is why this circuit is sloppy: it acts before there’s full confirmation. It frantically commands that we react to the present in ways that were imprinted long ago, with thoughts, emotions, reactions learned in response to events perhaps only dimly similar, but close enough to alarm the amygdala.

Thus a former army nurse, traumatized by the relentless flood of ghastly wounds she once tended in wartime, is suddenly swept away with a mix of dread, loathing, and panic — a repeat of her battlefield reaction triggered once again, years later, by the stench when she opens a closet door to find her toddler had stashed a stinking diaper there. A few spare elements of the situation is all that need seem similar to some past danger for the amygdala to trigger its emergency proclamation. The trouble is that along with the emotionally charged memories that have the power to trigger this crisis response can come equally outdated ways of responding to it.

The emotional brain’s imprecision in such moments is added to by the fact that many potent emotional memories date from the first few years of life, in the relationship between an infant and its caretakers. This is especially true for traumatic events, like beatings or outright neglect. During this early period of life other brain structures, particularly the hippocampus, which is crucial for narrative memories, and the neocortex, seat of rational thought, have yet to become fully developed. In memory, the amygdala and hippocampus work hand-in-hand; each stores and retrieves its special info independently. While the hippocampus retrieves info, the amygdala determines if that info has any emotional valence. But the amygdala, which matures very quickly in the infant’s brain, is much closer to fully formed at birth.

LeDoux turns to the role of the amygdala in childhood to support what has long been basic tenet of psychoanalytic thought: that the interactions of life’s earliest years lay down a set of emotional lessons based on the attunement and upsets in the contacts between infant and caretakers. These emotional lessons are so potent and yet so difficult to understand from the vantage point of adult life because, believes LeDoux, they’re stored in the amygdala as rough, wordless blueprints for emotional life. Since these earliest emotional memories are triggered in later life there’s no matching set of articulated thoughts about the response that takes us over. One reason we can be so baffled by our emotional outbursts, then, is that they often date from a time early in our lives when things were bewildering and we didn’t yet have words for comprehending events. We may have the chaotic feelings, but not the words for the memories that formed them.”

“Circuits from the limbic brain to the prefrontal lobes mean that the signals of strong emotion — anxiety, anger, and the like — can create neural static, sabotaging the ability of the prefrontal lobe to maintain working memory. That’s why when we are emotionally upset we say we ‘just can’t think straight’ — and why continual emotional distress can create deficits in a child’s intellectual abilities, crippling the capacity to learn.

These deficits, if more subtle, aren’t always tapped by IQ testing, though they show up through more targeted neuropsychological measures, as well as in child’s continual agitation and impulsivity. In one study, for example, primary school boys who had above-average IQ scores but nevertheless were doing poorly in school were found via these neuropsychological tests to have impaired frontal cortex functioning. They also were impulsive and anxious, often disruptive, and in trouble — suggesting faulty prefrontal control over their limbic urges. Despite their intellectual potential, these are the children at highest risk for problems like academic failure, alcoholism, and criminality — not because their intellect is deficient, but because their control over their emotional life is impaired.”

How To Be Emotionally Intelligent

“Evidence like this leads Dr. Damasio to the counter-intuitive position that feelings are typically indispensable for rational decisions; they point us in the right direction, where dry logic can then be of best use. While the world often confronts us with an unwieldly array of choices (How should you invest your savings? Whom should you marry?), the emotional learning that life has given us (such as the memory of a disastrous investment or a painful breakup) sends signals that streamline the decision by eliminating some options and highlighting others at the outset. In this way, Damasio argues, the emotional brain is as involved in reasoning as is the thinking brain.

The emotions, then, matter for rationality. In the dance of feeling and thought the emotional faculty guides our moment-to-moment decisions, working hand-in-hand with the rational mind, enabling — or disabling — thought itself. Likewise, the thinking brain plays an executive role in our emotions — except in those moments when emotions surge out of control and the emotional brain runs rampant.

In a sense we have 2 brains, 2 minds — and 2 different kinds of intelligence: rational and emotional. How we do in life is determined by both — it’s not just IQ, but emotional intelligence that matters. Indeed, intellect cannot work at its best without emotional intelligence. Ordinarily the complementarity of limbic system and neocortex, amygdala and prefrontal lobes, means each is a full partner in mental life. When these partners interact well, emotional intelligence rises — as does intellectual ability.

This turns the old understanding of the tension between reason and feeling on its head: it’s not that we want to do away with emotion and put reason in its place, as Erasmus had it, but instead find the intelligent balance of the two.”

“My concern is with a key set of these ‘other characteristics,’ emotional intelligence: abilities such as being able to motivate oneself and persist in the face of frustrations; to control impulse and delay gratification; to regulate one’s moods and keep distress from swamping the ability to think; to empathize and to hope.”

“Much evidence testifies that people who are emotionally adept — who know and manage their own feelings well, and who read and deal effectively with other people’s feelings — are at an advantage in any domain of life, whether romance or picking up the unspoken rules that govern success in organizational politics. People with well-developed emotional skills are also more likely to be content and effective in their own lives, mastering the habits of mind that foster their own productivity; people who cannot marshal some control over their emotional life fight inner battles that sabotage their ability for focused work and clear thought.”

“Those who tune in under duress can, by the very act of attending so carefully, unwittingly amplify the magnitude of their own reactions — especially if their tuning in is devoid of the equanimity of self-awareness. The result is that their emotions seem all the more intense. Those who tune out, who distract themselves, notice less about their own reactions, and so minimize the experience of their emotional response, if not the size of the response itself.

At the extremes, this means that for some people emotional awareness is overwhelming, while for others it barely exists.”

“Diener finds that women, in general, feel both positive and negative emotions more strongly than do men. And, sex differences aside, emotional life is richer for those who notice more. For one thing, this enhanced emotional sensitivity means that for such people the least provocation unleashes emotional storms, whether heavenly or hellish, while those at the other extreme barely experience any feeling even under the most dire circumstances.”

Managing Emotions

“The physiological beginnings of an emotion typically occur before a person is consciously aware of the feeling itself. For example, when people who fear snakes are shown pictures of snakes, sensors on their skin will detect sweat breaking out, a sign of anxiety, though they say they don’t feel any fear. This sweat shows up in such people even when a picture of a snake is presented so rapidly that they have no conscious idea of what, exactly, they just saw, let alone that they’re beginning to get anxious. As such preconscious emotional stirrings continue to build, they eventually become strong enough to break into awareness. Thus there are 2 levels of emotion, conscious and unconscious. The moment of an emotion coming into awareness marks its registering as such in the frontal cortex.

Emotions that simmer beneath the threshold of awareness can have a powerful impact on how we perceive and react, even though we have no idea they’re at work. Take someone who’s annoyed by a rude encounter early in the day, and then is peevish for hours afterward, taking affront where none is intended and snapping at people for no real reason. He may well be oblivious to his continuing irritability and will be surprised if someone calls attention to it, though it stews just out of his awareness and dictates his curt replies. But once that reaction is brought into awareness — once it registers in the cortex — he can evaluate things anew, decide to shrug off the feelings left earlier in the day, and change his outlook and mood.”

“Downs as well as ups spice life, but need to be in balance. In the calculus of the heart is the ratio of positive to negative emotions that determines the sense of well-being — at least that is the verdict from studies of mood in which hundreds of people have carried beepers that reminded them at random times to record their emotions at that moment. It’s not that people need to avoid unpleasant feelings to feel content, but rather that stormy feelings not go unchecked, displacing all pleasant moods. People who have strong episodes of anger or depression can still feel a sense of well-being if they have a countervailing set of equally joyous or happy times.”

“Managing our emotions is something of a full-time job: much of what we do — especially in our free time — is an attempt to manage mood. Everything from reading or watching TV to the activities and companions we choose can be a way to make ourselves feel better. The art of soothing ourselves is a fundamental life skill; some psychoanalytic thinkers see this as one of the most essential of all psychic tools. The theory holds that emotionally sound infants learn to soothe themselves by treating themselves as their caretakers have treated them, leaving them less vulnerable to the upheavals of the emotional brain.

As we’ve seen, the design of the brain means that we very often have little or no control over when we’re swept by emotion, nor over what emotion it’ll be. But we can have some say in how long an emotion will last. The issue arises not with garden-variety sadness, worry, or anger; normally such moods pass with time and patience. But when these emotions are of great intensity and linger past an appropriate point, they shade over into their distressing extremes — chronic anxiety, uncontrollable rage, depression.”

“Tice found that reframing a situation more positively was one of the most potent ways to put anger to rest.”

“Zillman sees 2 main way of intervening. One way of defusing anger is to seize on and challenge the thoughts that trigger the surges of anger, since it’s the original appraisal of an interaction that confirms and encourages the first burst of anger, and the subsequent reappraisals that fan the flames. Timing matters; the earlier in the anger cycle the more effective. Indeed, anger can be completely short-circuited if the mitigating info comes before the anger is acted on.

The power of understanding to deflate anger is clear from another of Zillmann’s experiments, in which a rude assistant (a confederate) insulted and provoked volunteers who were riding an exercise bike. When the volunteers were given the chance to retaliate against the rude experimenter (again, by giving a bad evaluation they thought would be used in weighting his candidacy for a job) they did so with an angry glee. But in one version of the experiment another confederate entered after the volunteers had been provoked, and just before the chance to retaliate; she told the provocative experimenter he had a phone call down the hall. As he left he made a snide remark to her too. But she took it in good spirits, explaining after he left that he was under terrible pressures, upset about his upcoming graduate orals. After that the irate volunteers, when offered the chance to retaliate, chose not to; instead they expressed compassion for his plight.

Such mitigating info allows a reappraisal of the anger-provoking events. But there’s a specific window of opportunity for this de-escalation. Zillmann finds it works well at moderate levels of anger; at high levels of rage it makes no difference because of what he calls ‘cognitive incapacitation’ — in other words, people can no longer think straight. When people were already highly enraged, they dismissed the mitigating info with ‘That’s just too bad!’ or ‘the strongest vulgarities English has to offer,’ as Zillmann put it with delicacy.”

“Once when I was about 13, in an angry fit, I walked out of the house vowing I’d never return. It was a beautiful day, and I walked far along lovely lanes, til gradually the stillness and beauty calmed and soothed me, and after some hours I returned repentant and almost melted. Since then when I’m angry, I do this if I can, and find it the best cure.

The account is by a subject in one of the very first scientific studies of anger, done in 1899. It still stands as a model of the second way of de-escalating anger: cooling off physiologically by waiting out the adrenal surge in a setting where there are not likely to be further triggers for rage. In an argument, for instance, that means getting away from the other person for the time being. During the cooling-off period, the angered person can put the brakes on the cycle of escalating hostile thought by seeking out distractions. Distraction, Zillmann finds, is a highly powerful mood-altering device, for a simple reason: It’s hard to stay angry when we’re having a pleasant time. The trick, of course, is to get anger to cool to the point where someone can have a pleasant time in the first place.”

“A cooling-down period won’t work if that time is used to pursue the train of anger-inducing thought, since each such thought is in itself a minor trigger for more cascades of anger. The power of distraction is that it stops that angry train of thought. In her survey of people’s strategies for handling anger, Tice found that distractions by and large help calm anger: TV, movies, reading, and the like all interfere with the angry thoughts that stoke rage. But, Tice found, indulging in treats such as shopping for oneself and eating don’t have much effect; it’s all too easy to continue with an indignant train of thought while cruising a shopping mall or devouring a piece of cake.

To these strategies add those developed by Redford Williams, who sought to help hostile people, who are at higher risk for heart disease, to control their irritability. One of his recommendations is to use self-awareness to catch cynical or hostile thoughts as they arise, and write them down. Once angry thoughts are captured this way, they can be challenged and reappraised, though, as Zillmann found, this approach works better before anger has escalated to rage.”

“Tice found that ventilating anger is one of the worst ways to cool down: outbursts of rage typically pump up the emotional brain’s arousal, leaving people feeling more angry, not less. Tice found that when people told of times they’d taken their rage out on the person who provoked it, the net effect was to prolong the mood rather than end it. Far more effective was when people first cooled down, and then, in a more constructive or assertive manner, confronted the person to settle their dispute. ‘Don’t suppress it. But don’t act on it.’”

“Among those in college, Tice found that eating was 3x as common a strategy for soothing sadness among women than men: men, on the other hand, were 5x as likely to turn to drinking or drugs when they felt down. The trouble with overeating or alcohol as antidotes, of course, is that they can easily backfire: eating to excess brings regret; alcohol is a central nervous system depressant, and so only adds to the effects of depression itself.”

“Another effective depression-lifter is helping others in need. Since depression feeds on ruminations and preoccupations with the self, helping others lifts us out of those preoccupations as we empathize with people in pain of their own.”

Performance

“From the earliest years of school, Asian children work harder than whites. Stanford sociologist Sanford Dorenbusch who studied more than 10k high school students found that Asian Americans spent 40% more time doing homework than did other students. ‘While most American parents are willing to accept a child’s weak areas and emphasize the strengths, for Asians, the attitude is that if you’re not doing well, the answer is to study later at night, and if you still don’t do well, to get up and study earlier in the morning. They believe that anyone can do well in school with the right effort.’ In short, a strong cultural work ethic translates into higher motivation, zeal, and persistence — an emotional edge.”

“Anxiety also sabotages academic performance of all kinds: 126 different studies of 36k+ people found that the more prone to worries a person is, the poorer their academic performance, no matter how measured — grades on tests, GPA, or achievement tests.

When people who are prone to worry are asked to perform a cognitive task such as sorting ambiguous objects into one of 2 categories, and narrate what’s going through their mind as they do so, it’s the negative thoughts — ‘I won’t be able to do this,’ ‘I’m just no good at this kind of test,’ and the like — that are found to most directly disrupt their decision-making. Indeed, when a comparison group of nonworriers was asked to worry on purpose for 15 minutes, their ability to do the same task deteriorated sharply. And when the worriers were given a 15-minute relaxation session — which reduced their level of worrying — before trying the task, they had no problem with it.

Test anxiety was first studied scientifically in the 60s by Richard Alpert, who confessed that his interest was piqued because as a student his nerves often made him do poorly on tests, while his colleague, Ralph Haber, found that the pressure before an exam actually helped him to do better. Their research, among other studies, showed that there’s 2 kinds of anxious students: those whose anxiety undoes their academic performance, and those who are able to do well despite the stress — or, perhaps, because of it. The irony of test anxiety is that the very apprehension about doing well on the test that, ideally, can motivate students like Haber to study hard in preparation and so do well can sabotage success in others. For people who are too anxious, like Alpert, the pretext apprehension interferes with the clear thinking and memory necessary to study effectively, while during the test it disrupts the mental clarity essential for doing well.

The number of worries that people report while taking a test directly predicts how poorly they’ll do on it. The mental resources expended on 1 cognitive task — the worrying — simply detract from the resources available for processing other info; if we’re preoccupied by worries that we’re going to flunk the test we’re taking, we have that much less attention to expend on figuring out the answers. Our worries become self-fulfilling prophecies, propelling us toward the very disaster they predict.”

“Good moods, while they last, enhance the ability to think flexibly and with more complexity, thus making it easier to find solutions to problems, whether intellectual or interpersonal. This suggests that one way to help someone think through a problem is to tell them a joke. Laughing, like elation, seems to help people think more broadly and associate more freely, noticing relationships that might’ve eluded them otherwise — a mental skill important not just in creativity, but in recognizing complex relationships and foreseeing the consequences of a given decision.”

“Even mild mood changes can sway thinking. In making plans or decisions people in good moods have a perceptual bias that leads them to be more expansive and positive in their thinking. This is partly because memory is state-specific, so that while in a good mood we remember more positive events; as we think over the pros and cons of a course of action while feeling pleasant, memory biases our weighing of evidence in a positive direction, making us more likely to do something slightly adventurous or risky, for example.

By the same token, being in a foul mood biases memory in a negative direction, making us more likely to contract into a fearful, overly cautious decision. Emotions out of control impede the intellect.”

“‘Students with high hope set themselves higher goals and know how to work hard to attain them. When you compare students of equivalent intellectual aptitude on their academic achievements, what sets them apart is hope.’”

“People who are optimistic see a failure as due to something that can be changed so that they can succeed next time around, while pessimists take the blame for failure, ascribing it to some lasting characteristic they’re helpless to change. These differing explanations have profound implications for how people respond to life. For example, in reaction to a disappointment such as being turned down for a job, optimists tend to respond actively and hopefully, by formulating a plan of action, say, or seeking out help and advice; they see the setback as something that can be remedied. Pessimists, by contrast, react to such setbacks by assuming there’s nothing they can do to make things go better the next time, and so do nothing about the problem; they see the setback as due to some personal deficit that will always plague them.

As with hope, optimism predicts academic success. In a study of 500 members of the incoming freshman class of ’84 at U of Penn, the students’ scores on a test of optimism were a better predictor of their actual grades freshman year than were their SAT scores or their high school grades.”

Reading Emotions

“In tests with 7,000+ people in the US and 18 other countries, the benefits of being able to read feelings from nonverbal cues included being better adjusted emotionally, more popular, more outgoing, and — perhaps not surprisingly — more sensitive.”

“Virtually from the day they’re born infants are upset when they hear another infant crying — a response some see as the earliest precursor of empathy. Development psychologists have found that infants feel sympathetic distress even before they fully realize that they exist apart from other people.”

“At this point in their development toddlers begin to diverge from one another in their overall sensitivity to other people’s emotional upsets, with some keenly aware and others tuning out. A series of National Institute of Mental Health studies showed that a large part of this difference in empathetic concern had to do with how parents disciplined their children. Children, they found, were more empathic when the discipline included calling strong attention to the distress their misbehavior caused someone else: ‘Look how sad you’ve made her feel’ instead of ‘That was naughty.’ They found too that children’s empathy is also shaped by seeing how others react when someone else is distressed; by imitating what they see, children develop a repertoire of empathic response, especially in helping other people who are distressed.”

“Through attunement mothers let their infants know they have a sense of what the infant is feeling. A baby squeals with delight, for example, and the mother affirms that delight by giving the baby a gentle shake, cooing, or matching the pitch of her voice to the baby’s squeal. Or a baby shakes his rattle, and she gives him a quick shimmy in response. In such an interaction the affirming message is in the mother more or less matching the baby’s level of excitement. Such small attachments give an infant the reassuring feeling of being emotionally connected, a message that Stern finds mothers send about once a minute when they interact with their babies.

Attunement is very different from simple imitation. ‘If you just imitate a baby,’ Stern told me, ‘that only shows you know what he did, not how he felt. To let him know you sense how he feels, you have to play back his inner feelings in another way. Then the baby knows he’s understood.’”

“When the emotional brain is driving the body with a strong reaction — the heat of anger, say — there can be little or no empathy. Empathy requires enough calm and receptivity so that the subtle signals of feeling from another person can be received and mimicked by one’s own emotional brain.”

“The callousness of psychopaths, Hare believes, is based in part on another physiological pattern he discovered, one that also suggests an irregularity in the workings of the amygdala and related circuits: psychopaths about to receive an electrical shock show no sign of the fear response that’s normal in people about to experience pain. Because the prospect of pain doesn’t trigger a surge of anxiety, Hare contends that psychopaths lack concern about future punishment for what they do. And because they themselves don’t feel fear, they have no empathy — or compassion — for the fear and pain of their victims.”

“We send emotional signals in every encounter, and those signals affect those we’re with. The more adroit we are socially, the better we control the signals we send; the reverse of polite society is, after all, simply a means to ensure that no disturbing emotional leakage will unsettle the encounter (a social rule that, when brought into the domain of intimate relationships is stifling). Emotional intelligence includes managing this exchange; ‘popular’ and ‘charming’ are terms we use for people whom we like to be with because their emotional skills make us feel good. People who are able to help others soothe their feelings have an especially valued social commodity; they’re the souls others turn to when in greatest emotional need. We’re all part of each other’s toolkit for emotional change, for better or worse.

Consider a remarkable demonstration of the subtlety with which emotions pass from one person to another. In a simple experiment 2 volunteers filled out a checklist about their moods at the moment, then simply sat facing each other quietly while waiting for an experimenter to return to the room. 2 minutes later she came back and asked them to fill out a mood checklist again. The pairs were purposely composed of 1 partner who was highly expressive of emotion and one who was deadpan. Invariably the mood of the one who was more expressive of emotions had been transferred to the more passive partner.

How does this magical transmission occur? The most likely answer is that we unconsciously imitate the emotions we see displayed by someone else, through an out-of-awareness motor mimicry of their facial expression, gestures, tone of voice, and other nonverbal markers of emotion. Through this imitation people re-create in themselves the mood of the other person.”

“In general, a high level of synchrony in an interaction means the people involved like each other. Frank Bernieri, the Oregon State psychologist who did these studies, told me, ‘How awkward or comfortable you feel with someone is at some level physical. You need to have compatible timing, to coordinate your movements, to feel comfortable. Synchrony reflects the depth of engagement between the partners; if you’re highly engaged, your moods begin to mesh, whether positive or negative.’

In short, coordination of moods is the essence of rapport, the adult version of the attunement a mother has with her infant. One determinant of interpersonal effectiveness, Cacioppo proposes, is how deftly people carry out this emotional synchrony. If they’re adept at attuning to people’s moods, or can easily bring others under the sway of their won, then their interactions will go more smoothly at the emotional level.”

“When two people interact, the direction of mood transfer is from the one who’s more forceful in expressing feelings to the one who’s more passive.”

“People who make an excellent social impression, for example, are adept at monitoring their own expression of emotion, are keenly attuned to the ways others are reacting, and so are able to continually fine-tune their performance, adjusting it to make sure they’re having the desired effect. In that sense, they’re like skilled actors.

However, if these interpersonal abilities aren’t balanced by an astute sense of one’s own needs and feelings and how to fulfill them, they can lead to a hollow social success — a popularity won at the cost of one’s true satisfaction.”

Relationships

“The net effect of these distressing attitudes is to create incessant crisis, since they trigger emotional hijackings more often and make it harder to recover from the resulting hurt and rage. Gottman uses the apt term flooding for this susceptibility to frequent emotional distress; flooded husbands or wives are so overwhelmed by their partner’s negativity and their own reaction to it that they’re swamped by dreadful, out-of-control feelings. People who are flooded cannot hear without distortion or respond with clear-headedness; they find it hard to organize their thinking, and they fall back on primitive reactions. They just want things to stop, or want to run, or sometimes, to strike back. Flooding is a self-perpetuating emotional hijacking.

Some people have high thresholds for flooding, easily enduring anger and contempt, while others may be triggered the moment their spouse makes a mild criticism. The technical description of flooding is in terms of heart rate rise from calm levels. At rest, women’s heart rates are about 82 beats / minute, men’s about 72. Flooding begins at about 10 beats / minute above a person’s resting rate; if the heart rate reaches 100 beats / minute (as it easily can do during moments of rage or tears), then the body is pumping adrenaline and other hormones that keep the distress high for some time. The moment of emotional hijacking is apparent from the heart rate: it can jump 10, 20, or even as many as 30 beats per minute within the space of a single heartbeat. Muscles tense; it can seem hard to breathe. There’s a swamp of toxic feelings, an unpleasant wash of fear and anger that seems inescapable and, subjectively, takes ‘forever’ to get over. At this point — full hijacking — a person’s emotions are so intense, their perspective so narrow, and their thinking so confused that there’s no hope of taking the other’s viewpoint or settling things in a reasonable way.

Of course, most spouses have such intense moments from time to time when they fight — it’s only natural. The problem for a marriage begins when one or another spouse feels flooded almost continually. Then the partner feels overwhelmed by the other partner, is always on guard for an emotional assault or injustice, becomes hypervigilant for any sign of attack, insult, or grievance, and is sure to overreact to even the least sign. If a husband is in such a state, his wife saying, ‘Honey, we’ve got to talk,’ can elicit the reactive thought, ‘She’s picking a fight again,’ and so trigger flooding. It becomes harder and harder to recover from physiological arousal, which in turn makes it easier for innocuous exchanges to be seen in a sinister light, triggering flooding all over again.

This is perhaps the most dangerous turning point for a marriage, a catastrophic shift in the relationship. The flooded partner has come to think the worst of the spouse virtually all the time, reading everything she does in a negative light. Small issues become major battles; feelings are hurt continually. With time, the partner who’s being flooded starts to see any and all problems in the marriage as severe and impossible to fix, since the flooding itself sabotages any attempt to work things out.”

“For couples who, understandably, find it awkward to monitor heart rate during a fight, it’s simpler to have a prestated agreement that allows one or another partner to call a time-out at the first signs of flooding in either partner. During that time-out period, cooling down can be helped along by engaging in a relaxation technique or aerobic exercise that might help the partners recover from this emotional hijacking.”

“A wife who feels in the heat of the moment that ‘he doesn’t care about my needs — he’s always so selfish’ might challenge the thought by reminding herself of a number of things her husband has done that are, in fact, thoughtful. This allows her to reframe the thought as ‘Well, he does show he cares about me sometimes, even though what he just did was thoughtless and upsetting to me.’ The latter formulation opens the possibility of change and a positive resolution; the former only foments anger and hurt.

The art of nondefensive speaking for couples centers around keeping what’s said to a specific complaint rather than escalating to a personal attack. Psychologist Haim Ginott, the grandfather of effective-communication programs, recommended that the best formula for a complain is ‘XYZ’: ‘When you did X, it made me feel Y, and I’d rather you did Z instead.’”

Discrimination

“Sylvia Skeeter was one of hundreds of people who came forward to testify to a widespread pattern of antiblack prejudice throughout the Denny’s chain, a pattern that resulted in a $54 million settlement of a class-action suit on behalf of thousands of black customers who’d suffered such indignities.

The plaintiffs included a detail of 7 black Secret Service agents who sat waiting for an hour for their breakfast while their white colleagues at the next table were served promptly — as they were all on their way to provide security for a visit by Pres. Clinton to the US Naval Academy. They also included a black girl with paralyzed legs in Tampa who sat in her wheelchair for 2 hours waiting for her food one night after prom. The pattern of discrimination, the class-action suit held, was due to the widespread assumption throughout the Denny’s chain — particularly at the level of district and branch manager — that black customers were bad for business. Today, largely as a result of the suit and publicity surrounding it, Denny’s is making amends to the black community. And every employee, especially managers, must attend sessions on the advantages of a multiracial clientele.”

“Waitresses or branch managers who took it upon themselves to discriminate against blacks were seldom, if ever, challenged. Instead, some managers seem to have encouraged them, at least tacitly, to discriminate, even suggesting policies such as demanding payment for meals in advance from black customers only, denying blacks widely advertised free birthday meals, or locking the doors and claiming to be closed if a group of black customers was coming. As attorney John Relman put it, ‘Denny’s management closed their eyes to what the field staff was doing. There must have been some message…which freed up the inhibitions of local managers to act on their racist impulses.’”

Emotions & Physical Health

“‘If someone scheduled for surgery tells me she’s panicked that day and doesn’t want to go through with it, I cancel the surgery,’ Nezhat explains, ‘Every surgeon knows that people who are extremely scared do terrible in surgery. They bleed too much, they have more infections and complications. They have a harder time recovering. It’s much better if they’re calm.’

The reason is straightforward: panic and anxiety hike blood pressure, and veins distended by pressure bleed more profusely when cut by the surgeon’s knife. Excess bleeding is one of the most troublesome surgical complications, one that can sometimes lead to death.”

“People who experienced chronic anxiety, long periods of sadness and pessimism, unremitting tension or incessant hostility, relentless cynicism, or suspiciousness, were found to have double the risk of disease — including asthma, arthritis, headaches, peptic ulcers, and heart disease (each representative of major, broad categories of disease). This order of magnitude makes distressing emotions as toxic a risk factor as, say, smoking or high cholesterol are for heart disease — a major threat to health.

“While the patients recounted incidents that made them mad, the pumping efficiency of their hearts dropped by 5%. Some of the patients showed a drop in pumping efficiency of 7% or greater — a range that cardiologists regard as a sign of a myocardial ischemia, a dangerous drop in blood flow to the heart itself.

The drop in pumping efficiency wasn’t seen with other distressing feelings, such as anxiety, nor during physical exertion; anger seems to be the one emotion that does most harm to the heart. While recalling the upsetting incident, the patients said they were only about half as mad as they had been while it was happening, suggesting that their hearts would’ve been even more greatly hampered during an actual angry encounter.”

“Being prone to anger was a stronger predictor of dying young than were other risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.”

“‘Take a 20-year-old who repeatedly gets angry. Each episode of anger adds an additional stress to the heart by increasing his heart rate and blood pressure. When that’s repeated over and over again, it can do damage,’ especially because the turbulence of blood flowing through the coronary artery with each heartbeat ‘can cause microtears in the vessel, where plaque develops. If your heart rate is faster and blood pressure is higher because you’re habitually angry, then over 30 years that may lead to a faster buildup of plaque, and so lead to coronary artery disease.’

Once heart disease develops, the mechanisms triggered by anger affect the very efficiency of the heart as a pump, as was shown in a study of angry memories in heart patients. The net effect is to make anger particularly lethal in those who already have heart disease. For instance, a Stanford study of 1k men and women who suffered from a first heart attack and then were followed for up to 8 years showed that those men who were most aggressive and hostile at the outset suffered the highest rate of second heart attacks. There were similar results in a Yale study of 929 men who’d survived heart attacks and were tracked for up to 10 years. Those who’d been rated as easily roused to anger were 3x more likely to die of cardiac arrest than those who were more even-tempered. If they also had high cholesterol levels, the added risk from anger was 5x higher.

The Yale researchers point out that it may not be anger alone that heightens the risk of death from heart disease, but rather intense negative emotionality of any kind that regularly sends surges of stress hormones through the body. But overall, the strongest scientific links between emotions and heart disease are to anger: a Harvard study asked 1,500+ people who’d suffered heart attacks to describe their emotional state in the hours before the attack. Being angry more than doubled the risk of cardiac arrest in people who already had heart disease; the heightened risk lasted for about 2 hours after the anger was aroused.”

“This anger-control training resulted in a second-heart-attack rate 44% lower than for those who hadn’t tried to change their hostility. A program designed by Williams has similar beneficial results. Like the Stanford program, it teaches basic elements of emotional intelligence, particularly mindfulness of anger as it begins to stir, the ability to regulate it once it has begun, and empathy. Patients are asked to jot down cynical or hostile thoughts as they notice them. If the thoughts persist, they try to short-circuit them by saying (or thinking), ‘Stop!’ And they’re encouraged to purposely substitute reasonable thoughts for cynical, mistrustful ones during trying situations — for instance, if an elevator is delayed, to search for a benign reason rather than harbor anger against some imagined thoughtless person who may be responsible for the delay. For frustrating encounters, they learn the ability to see things from the other person’s perspective — empathy is a balm for anger.”

“In a 1993 review of extensive research on the stress-disease link, Yale psychologist Bruce McEwen noted a broad spectrum of effects: compromising immune function to the point that it can speed the metastasis of cancer; increasing vulnerability to viral infections; exacerbating plaque formation leading to atherosclerosis and blood clotting leading to myocardial infection; accelerating the onset of Type I diabetes and the course of Type II diabetes; and worsening or triggering an asthma attack. Stress can also lead to ulceration of the GI tract, triggering symptoms in ulcerative colitis and in inflammatory bowel disease. The brain itself is susceptible to the long-term effects of sustained stress, including damage to the hippocampus, and so to memory. In general, says McEwen, ‘evidence is mounting that the nervous system is subject to ‘wear and tear’ as a result of stressful experiences.’

Particularly compelling evidence for the medical impact from distress has come from studies with infectious diseases such as colds, the flu, and herpes. We’re continually exposed to such viruses, but ordinarily our immune system fights them off — except that under emotional stress those defenses more often fail.”

“Among those with little stress, 27% came down with a cold after being exposed to the virus; among those with the most stressful lives, 47% got the cold — direct evidence that stress itself weakens the immune system.

Likewise, married couples who for 3 months kept daily checklists of hassles and upsetting events such as marital fights showed a strong pattern: 3–4 days after an especially intense batch of upsets, they came down with a cold or upper-respiratory infection. That lag period is precisely the incubation time for many common cold viruses, suggesting that being exposed while they were most worried and upset made them especially vulnerable.

The same stress-infection pattern holds for herpes — both oral and genital. Once people have been exposed to herpes, it stays latent in the body, flaring up from time to time. The activity of the herpes virus can be tracked by levels of antibodies to it in the blood. Using this measure, reactivation of the herpes virus has been found in med students undergoing year-end exams, in recently separated women, and among people under constant pressure from caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s.

The toll of anxiety isn’t just that it lowers the immune response; other research is showing adverse effects on the cardiovascular system. While chronic hostility and repeated episodes of anger seem to put men at the greatest risk for heart disease, the more deadly emotion in women may be anxiety and fear. In Stanford research with 1k+ people who’d suffered a first heart attack, those women who went on to suffer a second were marked by high levels of fearfulness and anxiety. In many cases the fearfulness took the form of crippling phobias: after their first heart attack the patients stopped driving, quit their jobs, or avoided going out.

The insidious physical effects of mental stress and anxiety — the kind produced by high-pressure jobs, or high-pressure lives, such as that of a single mom juggling day care and a job — are being pinpointed at an anatomically fine-grained level. For example, Stephen Manuck put 30 volunteers through a rigorous, anxiety-ribbed ordeal in a lab while he monitored the men’s blood, assaying a substance secreted by blood platelets called ATP, which can trigger blood-vessel changes that may lead to heart attacks and strokes. While the volunteers were under intense stress, their ATP levels rose sharply, as did their heart rate and blood pressure.

Understandably, health risks seem greatest for those whose jobs are high in ‘strain’: having high-pressure performance demands while having little or no control over how to get the job done (a predicament that gives bus drivers, for instance, a high rate of hypertension). For example, in a study of 569 patients with colorectal cancer and a matched comparison group, those who said that in the previous 10 years they’d experienced severe on-the-job aggravation were 5.5x more likely to have developed the cancer compared to those with no such stress in their lives.”

“Of 100 patients who received bone marrow transplants, 12 of the 13 who’d been depressed died within the first year, while 34 of the remaining 87 were still alive 2 years later. And in patients with chronic kidney failure who were receiving dialysis, those who were diagnosed with major depression were most likely to die within the following 2 years; depression was a stronger predictor of death than any medical sign. Here the route connecting emotion to medical status wasn’t biological but attitudinal: The depressed patients were much worse about complying with their medical regimens — cheating on their diets, for example, which put them at higher risk.

Heart disease too seems to be exacerbated by depression. In a study of 3k middle-aged people tracked for 12 years, those who felt a sense of nagging despair and hopelessness had a heightened rate of death from heart disease. And for the 3% who were most severely depressed, the death rate from heart disease, compared to the rate for those with no feelings of depression, was 4x greater.

Depression seems to pose a particularly grave medical risk for heart attack survivors. In a study of patients in a Montreal hospital who were discharged after being treated for a first heart attack, depressed patients had a sharply higher risk of dying within the following 6 months. Among the 1 in 8 patients who were seriously depressed, the death rate was 5x higher than for others with comparable disease — an affect as great as that of major medical risks for cardiac death, such as left ventricular dysfunction or a history of previous heart attacks. Among the possible mechanisms that might explain why depression so greatly increases the odds of a later heart attack are its effects on heart rate variability, increasing the risk of fatal arrhythmias.

Depression has also been found to complicate recovery from hip fracture. In a study of elderly women with hip fracture, several thousand were given psychiatric evaluations on their admission to the hospital. Those who were depressed on admission stayed an average of 8 days longer than those with comparable injury but no depression, and were only a third as likely ever to walk again. But depressed women who had psychiatric help for their depression along with other medical care needed less physical therapy to walk again and had fewer re-hospitalizations over the 3 months after their return home from the hospital.

Likewise, in a study of patients whose condition was so dire that they were among the top 10% of those using medical services — often because of having multiple illnesses, such as both heart disease and diabetes — about 1 in 6 had serious depression. When these patients were treated for the problem, the number of days per year that they were disabled dropped from 79 to 51 for those who had major depression, and from 62 days per year to just 18 in those who had been treated for mild depression.”

“As with depression, there are medical costs to pessimism — and corresponding benefits from optimism. For example, 122 men who had their first heart attack were evaluated on their degree of optimism or pessimism. 8 years later, of the 25 most pessimistic men, 21 had died; of the 25 most optimistic, just 6 had died. Their mental outlook proved a better predictor of survival than any medical risk factor, including the amount of damage to the heart in the first attack, artery blockage, cholesterol level, or blood pressure. And in other research, patients going into artery bypass surgery who were most optimistic had a much faster recovery and fewer medical complications during and after surgery than did more pessimistic patients.

Like its near cousin optimism, hope has healing power. People who have a great deal of hopefulness are understandably, better able to bear up under trying circumstances, including medical difficulties. In a study of people paralyzed from spinal injuries, those who had more hope were able to gain greater levels of physical mobility compared to other patients with similar degrees of injury, but who felt less hopeful. Hope is especially telling in paralysis from spinal injury, since this medical tragedy typically involves a man who’s paralyzed in his 20s by an accident and will remain so for the rest of his life. How he reacts emotionally will have broad consequences for the degree to which he’ll make the efforts that might bring him greater physical and social functioning.

Just why an optimistic or pessimistic outlook should have health consequences is open to any of several explanations. One theory proposes that pessimism leads to depression, which in turn interferes with the resistance of the immune system to tumors and infection — an unproven speculation. Or it may be that pessimists neglect themselves — some studies have found that pessimists smoke and drink more, and exercise less, than optimists, and are generally more careless about their health habits. Or it may one day turn out that the physiology of hopefulness is itself somehow helpful biologically to the body’s fight against disease.”

Social Support

“Isolation itself, a 1987 report in Science concluded, ‘is as significant to mortality rates as smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, and lack of physical exercise.’ Indeed, smoking increases mortality risk by a factor of just 1.6, while social isolation does so by a factor of 2, making it a greater health risk.”

“Of those who felt they had strong emotional support from their spouse, family, or friends, 54% survived the transplants after 2 years, vs. just 20% among those who reported little such support. Similarly, elderly people who suffer heart attacks, but have 2+ people in their lives they can rely on for emotional support, are more than twice as likely to survive longer than a year after an attack than are those people with no such support.

Perhaps the most telling testimony to the healing potency of emotional ties is a 1993 Swedish study. All the men living in the Swedish city of Goteborg who were born in 1933 were offered a free med exam; 7 years later the 752 men who’d come for the exam were contacted again. Of these, 41 had died in the intervening years.

Men who’d originally reported being under intense emotional stress had a death rate 3x higher than those who said their lives were calm. The emotional distress was due to events such as serious financial trouble, feeling insecure at work or being forced out of a job, being the object of a legal action, or going through a divorce. Having had 3+ of these troubles within the year before the exam was a stronger predictor of dying within the ensuing 7 years than were medical indicators such as high blood pressure, high concentrations of blood triglycerides, or high serum cholesterol levels.

Yet among men who said they had a dependable web of intimacy — a wife, close friends, and the like — there was no relationship whatever between high stress levels and death rate. Having people to turn to and talk with, people who could offer solace, help, and suggestions, protected them from the deadly impact of life’s rigors and trauma.

The quality of relationships as well as their sheer number seems key to buffering stress. Negative relationships take their own toll. Marital arguments, for example, have a negative impact on the immune system. One study of college roommates found that the more they disliked each other, the more susceptible they were to colds and the flu, and the more frequently they went to doctors. John Cacioppo, who did the study, told me, ‘It’s the most important relationships in your life, the people you see day in and day out, that seem to be crucial for your health. And the more significant the relationship is in your life, the more it matters for your health.’”

“Getting people to talk about the thoughts that trouble them most has a beneficial medical effect. His method is remarkably simple: he asks people to write, for 15–20 minutes a day over 5 or so days, about, for example, ‘the most traumatic experience of your entire life,’ or some pressing worry of the moment. What people write can be kept entirely to themselves if they want.

The net effect of this confessional is striking: enhanced immune function, significant drops in health-center visits in the following 6 months, fewer days missed from work, and even improved liver enzyme function. Moreover, those whose writing showed most evidence of turbulent feelings had the greatest improvements in their immune function. A specific pattern emerged as the ‘healthiest’ way to ventilate troubling feelings: at first expressing a high level of sadness, anxiety, anger — whatever troubling feelings the topic brought up; then over the course of the next several days weaving a narrative, finding some meaning in the trauma or travail.”

“Women with advanced breast cancer who went to weekly meetings with others survived twice as long as did women with the same disease who faced it on their own.

All the women received standard medical care; the only difference was that some also went to the groups, where they were able to unburden themselves with others who understood what they faced and were willing to listen to their fears, their pain, and their anger. Often this was the only place where the women could be open about their emotions, because other people in their lives dreaded talking with them about the cancer and their imminent death. Women who attended the groups lived for 37 additional months, on average, while those with the disease who didn’t go to the groups died, on average, in 19 months — a gain in life expectancy for such patients beyond the reach of any medication or other medical treatment.”

Parenting Emotional Skills

“The U of Wash team found that when patients are emotionally adept, compared to those who handle feelings poorly, their children — understandably — get along better with, show more affection toward, and have less tension around their parents. But beyond that, these children also are better at handling their own emotions, are more effective at soothing themselves when upset, and get upset less often. The children are also more relaxed biologically, with lower levels of stress hormones and other physiological indicators of emotional arousal (a pattern that, if sustained through life, might well augur better physical health). Other advantages are social: these children are more popular with and are better-liked by their peers, and are seen by their teachers as more socially skilled. Their parents and teachers alike rate these children as having fewer behavioral problems such as rudeness or aggressiveness. Finally, the benefits are cognitive: these children can pay attention better, and so are more effective learners. Holding IQ constant, the 5-year-olds whose parents were good coaches had higher achievement scores in math and reading when they reached 3rd grade (a powerful argument for teaching emotional skills to help prep children for learning as well as life).”

“A child’s readiness for school depends on the most basic of all knowledge, how to learn. The report lists the 7 key ingredients of this crucial capacity — all related to emotional intelligence.

- Confidence. A sense of control and mastery of one’s body, behavior, and world; the child’s sense that he’s more likely than not to succeed at what he undertakes, and that adults will be helpful.

- Curiosity. The sense that finding out about things is positive and leads to pleasure.

- Intentionality. The wish and capacity to have an impact, and to act upon that with persistence. This is related to a sense of competence, of being effective.

- Self-control. The ability modulate and control one’s own actions in age-appropriate ways; a sense of inner control.

- Relatedness. The ability to engage with others based on the sense of being understood by and understanding others.

- Capacity to communicate. The wish and ability to verbally exchange ideas, feelings, and concepts with others. This is related to a sense of trust in others and of pleasure in engaging with others, including adults.

- Cooperativeness. The ability to balance one’s own needs with those of others in a group activity.”

Personality

“As Joseph LeDoux, the neurologist who discovered the amygdala’s hair-trigger role in emotional outbursts, conjectures, ‘Once your emotional system learns something, it seems you never let it go. What therapy does is teach you to control it — it teaches your neocortex how to inhibit your amygdala. The propensity to act is suppressed, while your basic emotion about it remains in a subdued form.’

Given the brain architecture that underlies emotional re-learning, what seems to remain, even after successful psychotherapy, is a vestigial reaction, a remnant of the original sensitivity or fear at the root of a troubling emotional pattern. The prefrontal cortex can refine or put the brakes on the amygdala’s impulse to rampage, but cannot keep it from reacting in the first place. Thus while we cannot decide when we have our emotional outbursts, we have more control over how long they lost. A quicker recovery time from such outbursts may well be one mark of emotional maturity.”

“Kagan posits that there are at least 4 temperamental types — timid, bold, upbeat, and melancholy — and that each is due to a different pattern of brain activity. There are likely innumerable differences in temperamental endowment, each based in innate differences in emotional circuitry; for any given emotion people can differ in how easily it triggers, how long it lasts, how intense it becomes. Kagan’s work concentrates on one of these patterns: the dimension of temperament that runs from boldness to timidity.

For decades, moms have been bringing their infants and toddlers to Kagan’s Lab for Child Development to take part in studies. It was there that Kagan and his coresearchers noticed early signs of shyness in a group of 21-month-old toddlers brought for experimental observations. In free play with other toddlers, some were bubbly and spontaneous, playing with other babies without the least hesitation. Others, though, were uncertain and hesitant, hanging back, clinging to their moms, quietly watching the others at play. Almost 4 years later, when these same children were in kindergarten, Kagan’s group observed them again. Over the intervening years none of the outgoing children had become timid, while 2/3 of the timid ones were still reticent.

Kagan finds that children who are overly sensitive and fearful grow into shy and timorous adults.”

“The difference between cautious Tom and bold Ralph, Kagan believes, lies in the excitability of a neural circuit centered on the amygdala. Kagan proposes that people like Tom, who’re prone to fearfulness, are born with a neurochemistry that makes this circuit easily aroused, and so they avoid the unfamiliar, shy away from uncertainty, and suffer anxiety. Those who have a nervous system calibrated with a much higher threshold for amygdala arousal are less easily frightened, more naturally outgoing, and eager to explore new places and meet new people.”

“Part of Kagan’s evidence comes from observations of cats that are unusually timid. About 1 in 7 housecats has a pattern of fearfulness akin to the timid children’s: they draw away from novelty, they’re reluctant to explore new territory, and they attack only the smallest rodents, being too timid to take on larger ones that their more courageous feline peers would pursue with gusto. Direct brain probes have found that portions of the amygdala are unusually excitable in these timid cats, especially when, for instance, they hear a threatening howl from another cat.

The cats’ timidity blossoms at about 1 month of age, which is the point when their amygdala matures enough to take control of the brain circuitry to approach or avoid. 1 month in kitten brain maturation is akin to 8 months in a human infant; it’s at 8–9 months, Kagan notes, that ‘stranger’ fear appears in babies — if the baby’s mom leaves the room and there’s a stranger present, the result is tears. Timid children, Kagan postulates, may have inherited chronically high levels of norepinephrine or other brain chemicals that active the amygdala and so create a low threshold of excitability, making the amygdala more easily triggered.”

“This dimension of temperament — ebullience at one end, melancholy at the other — seems linked to the relative activity of the right and left prefrontal areas, the upper poles of the emotional brain. That insight has emerged largely from the work of Richard Davidson. He discovered that people who have greater activity in the left frontal lobe, compared to the right, are by temperament cheerful; they typically take delight in people and in what life presents them with, bouncing back from setbacks. But those with relatively greater activity on the right side are given to negativity and sour moods, and are easily fazed by life’s difficulties; in a sense, they seem to suffer because they can’t turn off their worries and depressions.

In one of his experiments volunteers with the most pronounced activity in the left frontal areas were compared with the 15 who showed most activity on the right. Those with marked right frontal activity showed a distinctive pattern of negativity on a personality test: they see catastrophe in the smallest thing — prone to funks and moodiness, and suspicious of a world they [see] as fraught with overwhelming difficulties and lurking dangers. By contrast to their melancholy counterparts, those with stronger left frontal activity saw the world very differently. Sociable and cheerful, they typically felt a sense of enjoyment, were frequently in good moods, had a strong sense of self-confidence, and felt rewardingly engaged in life. Their scores on psychological tests suggested a lower lifetime risk for depression and other emotional disorders.

People who have a history of clinical depression, Davidson found, had lower levels of brain activity in the left frontal lobe, and more on the right, than did people who’d never been depressed. He found the same pattern in patients newly diagnosed with depression. Davidson speculates that people who overcome depression have learned to increase the level of activity in their left prefrontal lobe.”

“The tendency toward a melancholy or upbeat temperament — like that toward timidity or boldness — emerges within the first year of life, a fact that strongly suggests it too is genetically determined. Like most of the brain, the frontal lobes are still maturing in the first few months of life, and so their activity can’t be reliably measured until the age of 10 months or so. But in infants that young, Davidson found that the activity level of the frontal lobes predicted whether they’d cry when their moms left the room. The correlation was virtually 100%: of dozens of infants tested this way, every infant who cried had more brain activity on their right side, while those who didn’t had more on the left.

Still, even if this basic dimension of temperament is laid down from birth, or very nearly from birth, those of us who have the morose pattern aren’t necessarily doomed to go through life brooding and crotchety. The emotional lessons of childhood can have a profound impact on temperament, either amplifying or muting an innate predisposition. The great plasticity of the brain in childhood means that experiences during those years can have a lasting impact on the sculpting of neural pathways for the rest of life.”

“The encouraging news from Kagan’s studies is that not all fearful infants grow up hanging back from life — temperament isn’t destiny. The overexcitable amygdala can be tamed, with the right experiences. What makes the difference are the emotional lessons and responses children learn as they grow. For the timid child, what matters at the outset is how they’re treated by their parents, and so how they learn to handle their natural timidness. Those parents who engineer gradual emboldening experiences for their children offer them what may be a lifelong corrective to their fearfulness.

Almost 1 in 3 infants who come into the world with all the signs of an overexcitable amygdala have lost their timidness by the time they reach kindergarten. From observations of these once-fearful children at home, it’s clear that parents, and especially moms, play a major role in whether an innately timid child grows bolder with time or continues to shy away from novelty and be upset by challenge. Kagan’s team found that some of the mothers held to the philosophy that they should protect their timid toddlers from whatever was upsetting; others felt it was more important to help their timid child learn how to cope with these upsetting moments, and so adapt to life’s small struggles. The protective belief seems to have abetted the fearfulness, probably by deceiving the youngsters of opportunities for learning how to overcome their fears. The ‘learn to adapt’ philosophy seems to have helped fearful children become braver.

Home observations when the babies were about 6 months old found that the protective mothers, trying to soothe their infants, picked them up and held them when they fretted or cried, and did so longer than those moms who tried to help their infants learn to master these moments of upset. The ratio of times the infants were held when calm and when upset showed that the protective moms held their infants much longer during the upsets than the calm periods.

Another difference emerged when the infants were around 1; the protective moms were more lenient and indirect in setting limits for their toddlers when they were doing something that might be harmful, such as mouthing an object they might swallow. The other moms, by contrast, were emphatic, setting firm limits, giving direct commands, blocking the child’s actions, insisting on obedience.

Why should firmness lead to a reduction in fearfulness? Kagan speculates that there’s something learned when a baby has his steady crawl toward what seems to him an intriguing object (but to his mom a dangerous one) interrupted by her warning. ‘Get away from that!’ The infant is suddenly forced to deal with a mild uncertainty. The repetition of this challenge hundreds and hundreds of times during the first year of life gives the infant continual rehearsals, in small doses, of meeting the unexpected in life. For fearful children that’s precisely the encounter that has to be mastered, and manageable doses are just right for learning the lesson. When the encounter takes place with parents who, though loving, don’t rush to pick up and soothe the toddler over every little upset, he gradually learns to manage such moments on his own. By age 2, when these formerly fearful toddlers are brought back to Kagan’s lab, they’re far less likely to break out into tears when a stranger frowns at them, or an experimenter puts a blood-pressure cuff around their arm.”

“Throughout childhood some timid children grow bolder as experience continues to mold the key neural circuitry. One of the signs that a timid child will be more likely to overcome this natural inhibition is having a higher level of social competence: being cooperative and getting along with other children; being empathic; prone to giving and sharing, and considerate; and being able to develop close friendships. These traits marked a group of children first identified as having a timid temperament at age 4, who shook it off by the time they were 10.”

“It’s easy to see why the more emotionally competent — though shy by temperament — children spontaneously outgrew their timidity. Being more socially skilled, they were far more likely to have a succession of positive experiences with other children. Even if they were tentative about, say, speaking to a new playmate, once the ice was broken they were able to shine socially. The regular repetition of such social success over many years would naturally tend to make the timid more sure of themselves.

These advances toward boldness are encouraging; they suggest that even innate emotional patterns an change to some degree. A child who comes into the world easily frightened can learn to be calmer, or even outgoing, in the face of the unfamiliar. Fearfulness — or any other temperament — may be part of the biological givens of our emotional lives, but we’re not necessarily limited to a specific emotional menu by our inherited traits. There’s a range of possibility even within genetic constraints.”