Todd Haynes’ new film Dark Waters wades into some of the most complicated topics in public health, chemistry, and the law to dramatize the story of environmental attorney Robert Bilott and his nearly two decades of civil actions against DuPont. Late in the film, a disillusioned Bilott (Mark Ruffalo), up against a wall, imagines that the multinational corporation, the likes of which he once defended, might be setting him up to be a cautionary tale for all their would-be litigants: “Look, everybody, even he can’t crack the maze,” Bilott says, “and he’s helped build it.”

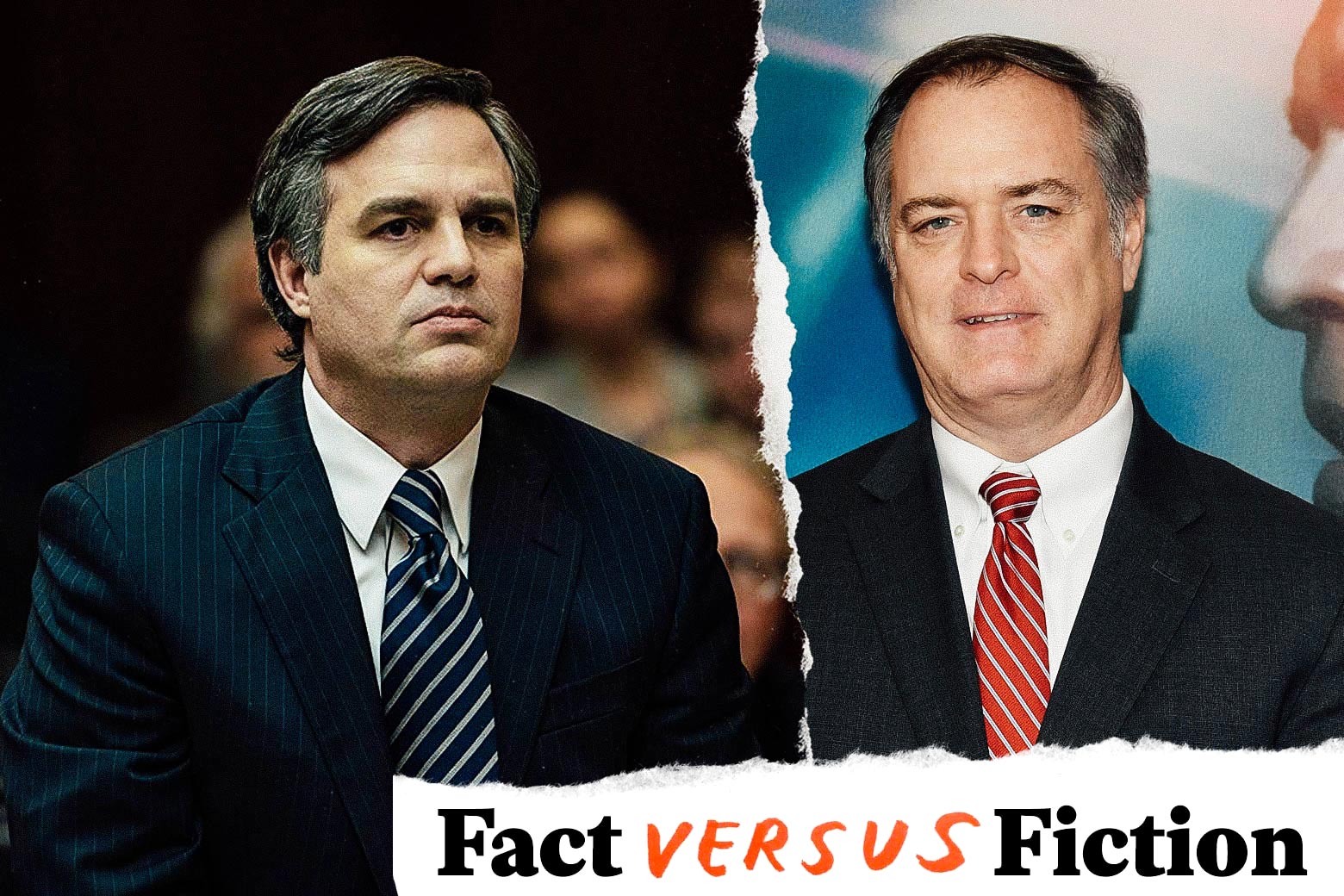

How accurately does Dark Waters depict the twists and turns of this maze? We consulted a variety of sources, including Nathaniel Rich’s 2016 New York Times Magazine feature “The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare” (upon which the movie is based), Bilott’s own book, other longform articles, and attorney Harry Deitzler (the personal-injury lawyer played in the movie by Bill Pullman), to help sort out what’s true and what’s embellished.

Robert Bilott

In real life as in the film, Bilott’s earliest professional experiences after law school were working on behalf of chemical companies for his employer, Taft Stettinius & Hollister, providing the firm’s corporate clients with guidance on how best to comply with the so-called Superfund law passed by Congress in 1980 to regulate sites tainted with hazardous substances. As in the movie, he at first had a cozy relationship with DuPont, though some of the details of the relationship in the movie are invented. For example, the DuPont executive played by Victor Garber, “Phil Donnelly,” seems to be a composite, and the scene where he turns on Bilott, hissing at him, “Fuck you, hick,” appears to be invented.

Like the movie, Rich’s article portrays Bilott as an unassuming and understated man driven by an innate sense of decency. As one of Bilott’s colleagues told the New York Times, ‘‘To say that Rob Bilott is understated is an understatement.’’ It’s also true that Bilott did not have the same Ivy League pedigree of many of his colleagues at Taft, having been raised on Air Force bases across the continental United States and West Germany, and it was through these working-class connections that he was introduced to the Tennant family farm case. Bilott did marry a fellow lawyer, Sarah Barlage, who left her career defending corporations against worker’s compensation claims to raise their sons.

The film’s portrayal of the physical toll that the excruciating, decadeslong legal battle against DuPont seems to have had on Bilott’s health is also accurate. As he does in the film, the real Bilott did begin to experience strange symptoms in 2010 similar to the strokelike transient ischemic attack seen in the movie. In his memoir, Exposure: Poisoned Water, Corporate Greed, and One Lawyer’s Twenty-Year Battle Against DuPont, published earlier this year, Bilott says that doctors could only really diagnose the issue as “unusual brain activity” after an MRI similar to the one he undergoes in the film.

Trial lawyer Harry Deitzler, who’s played by Bill Pullman in the film, told Slate in a telephone interview that while Dark Waters captured Bilott’s sense of “commitment” and “general modesty,” it was less accurate in its depiction on one particular issue: Robert Bilott has not been known to be an especially big fan of Mai Tais, either in general or on special occasions. “I don’t recall him drinking,” Deitzler says. “I noticed that in at least one of the scenes where I was portrayed. Bill Pullman was portraying me, and he’s taller and younger, and everyone appeared to be drinking. That’s Hollywood, I guess.” (Bilott has not yet responded to my email and telephone inquiries about whether he has ever enjoyed a celebratory Mai Tai or any other tropical, rum-based cocktail.)

The Tennant Family Farm

As a linchpin bolstering Dark Waters’ case as a message movie, the events depicted on the Tennant cattle farm in Parkersburg, West Virginia, really ought to be accurate, and for the most part, they are. Wilbur Tennant’s brother Jim really was a DuPont employee plagued with a serious ailment his doctors could not diagnose, and the chemical company did buy his 66 acres of the family’s 600-some-acre property in the 1980s. DuPont then really did proceed to turn that plot into a dumping ground for sludge that it knew to be toxic, going so far as to quietly conduct tests for perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, in the nearby river and expressing concern for the health of the Tennants’ livestock in internal documents nearly a decade before they would be denying culpability and blaming the Tennants in court. The symptoms shown in the movie—including such discolorations as blackened teeth—are also similar to the ones that Tennant really did videotape before sending the tapes to Bilott.

The sometimes contentious tenor of Bilott’s relationship with Wilbur Tennant is also true to life. As Bilott recollected in a panel discussion with the Washington Post, it was Wilbur’s obstinate refusal to simply take his monetary settlement and walk away that compelled Bilott to keep pursuing new legal avenues to hold DuPont to account. “He knew his neighbors and his community was being poisoned,” Bilott told the Post. “It was really his dedication to bringing that out that really inspired me to try to find a way to address the bigger problem.”

Amazingly, the Pakula-esque paranoid thriller scene, in which Wilbur Tennant spots a low-level helicopter hovering ominously over his property, uses the scope of his hunting rifle to better examine the vehicle, and scares it off in the process, did in fact occur. As Bilott details in Exposure, the April 23, 2001, incident was eventually confirmed between his legal team and DuPont’s. According to the book, DuPont had commissioned a photographer to take aerial photos of the property as part of its defense. DuPont’s lawyers had a different perspective on the incident, however, writing in an email, “It is a federal offense to threaten violence against an aircraft carrying passengers” and “Please be advised that the helicopter pilot has indicated that he will pursue today’s incident with federal authorities.”

While DuPont did also conduct walk-throughs and physical searches of the Tennant’s belongings, deeply alienating some of the family’s renters, the movie depicts some of Tennant’s evidence going mysteriously missing. I could find no record of any such incident taking place.

DuPont

As unbelievable as it may sound, DuPont really did, in the 1960s, offer some of its staff Teflon-laced cigarettes as a human experiment into the potential side effects of the PFOA-produced nonstick material, as the movie recounts. As company scientists noted in internal documents, “Nine out of ten people in the highest-dosed group were noticeably ill for an average of nine hours with flu-like symptoms that included chills, backache, fever, and coughing.”

Similarly, DuPont’s presence in the Ohio and West Virginia “Chemical Valley” regions really did resemble the company town vibe portrayed in Dark Waters, with citizens frequently too enthralled by the multinational’s economic benefits to question its impact on their health and safety.

Taft Stettinius & Hollister

While the character of the hand-wringing Taft lawyer James Ross, portrayed by The Good Place’s William Jackson Harper, seems to have been invented, along with the scene where Ross suggests that Bilott’s class-action suit might read to the public as nothing more than “a shakedown of an iconic American company,” Bilott did tell the New York Times that he “perceived that there were some ‘What the hell are you doing?’ responses” within the firm. Deitzler suggests it would have been a historic first for no partners at a firm of Taft’s size and corporate client base to express qualms about a class-action suit of this kind.

Similarly, Bilott’s boss, Tom Terp (Tim Robbins), is not on the record as ever having threatened to cut Bilott’s balls off “and feed them to DuPont himself” if his subordinate were to ever again unilaterally send internal documents found via discovery to a federal regulatory agency or speak on his findings to Congress. Of Bilott’s “Famous Letter” to the EPA, Terp told the Times that he didn’t recall if there was any particular reaction internally and that the partners at Taft were “proud of the work that he has done.’’

The Lubeck Letter

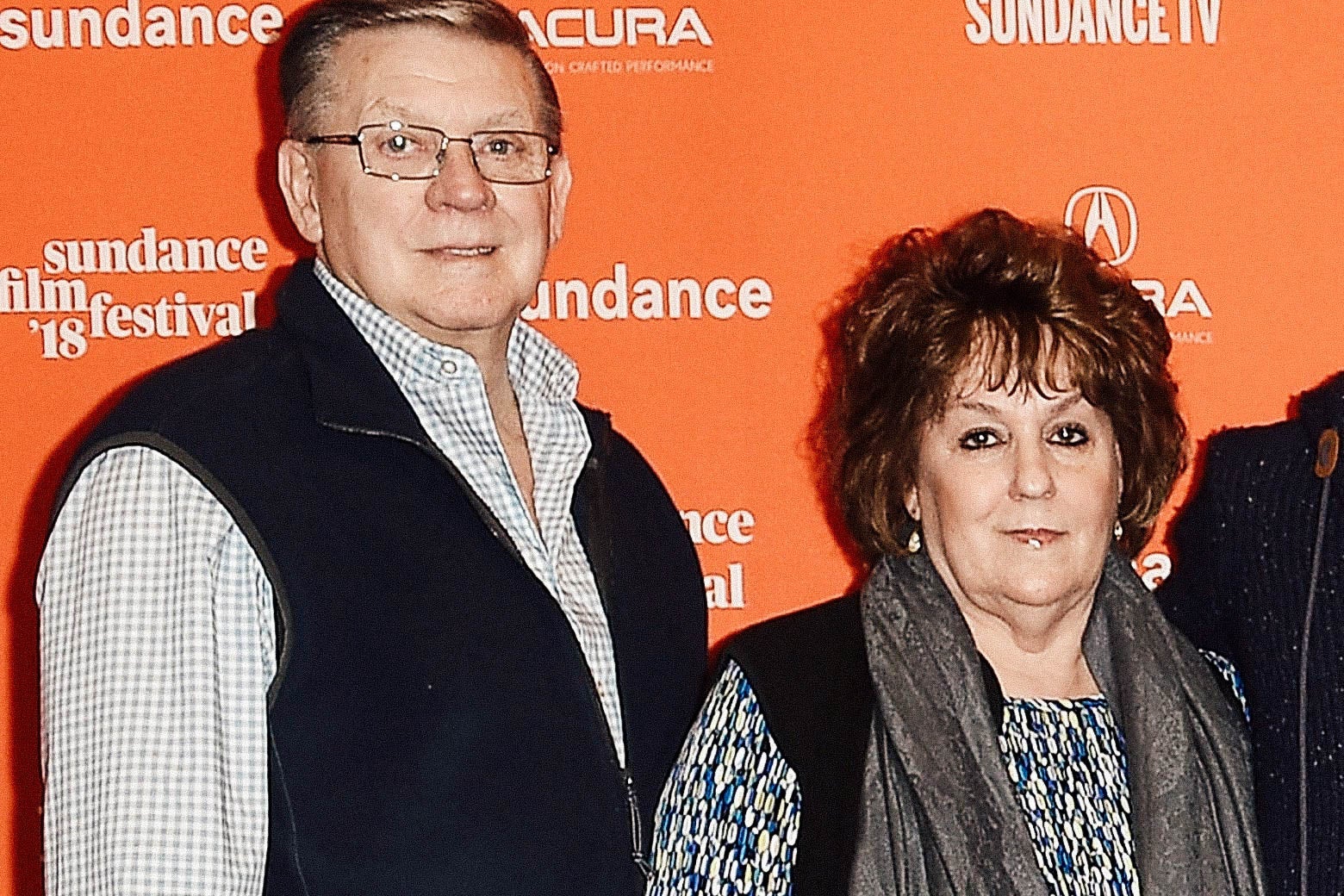

The Kiger family, teacher Joseph Kiger and his wife, Darlene, really did receive a cagey and curiously worded letter from the local Lubeck water district in October 2000 notifying them that an unregulated chemical named PFOA was present in their drinking water at ‘‘low concentrations.” And, as the film intimates, this letter, delivered on the public utility’s letterhead, was first reviewed by DuPont and started the clock on the “statute of limitations.” Much of the biographical information about the Kiger family, including Darlene’s first marriage to a DuPont engineer who came home sick and called it the “Teflon flu,” also checks out.

As in the movie, these events really did lead to a large class-action suit that triggered a massive epidemiological study that, after a yearslong wait, showed there really was a “probable link” between PFOA and certain conditions, including high cholesterol, kidney cancer, and testicular cancer, though the movie depicts one scientist going so far as to tell Bilott that the results are “irrefutable.” (DuPont has continued to deny that it did anything wrong.)

But what about the alarming moment when a fire breaks out at the home of Joseph Kiger’s father, who shares his name? The film seems to imply that the fire might have been an arson attempt that hit the wrong house, though it doesn’t suggest who might have lit it. Still, in other scenes, such as when Bilott falsely suspects his car might be rigged with an explosive, it’s made clear that the events of the film are leading some of its characters to fear things that aren’t really there. Just because there really is something in the water doesn’t mean you can’t also be paranoid.