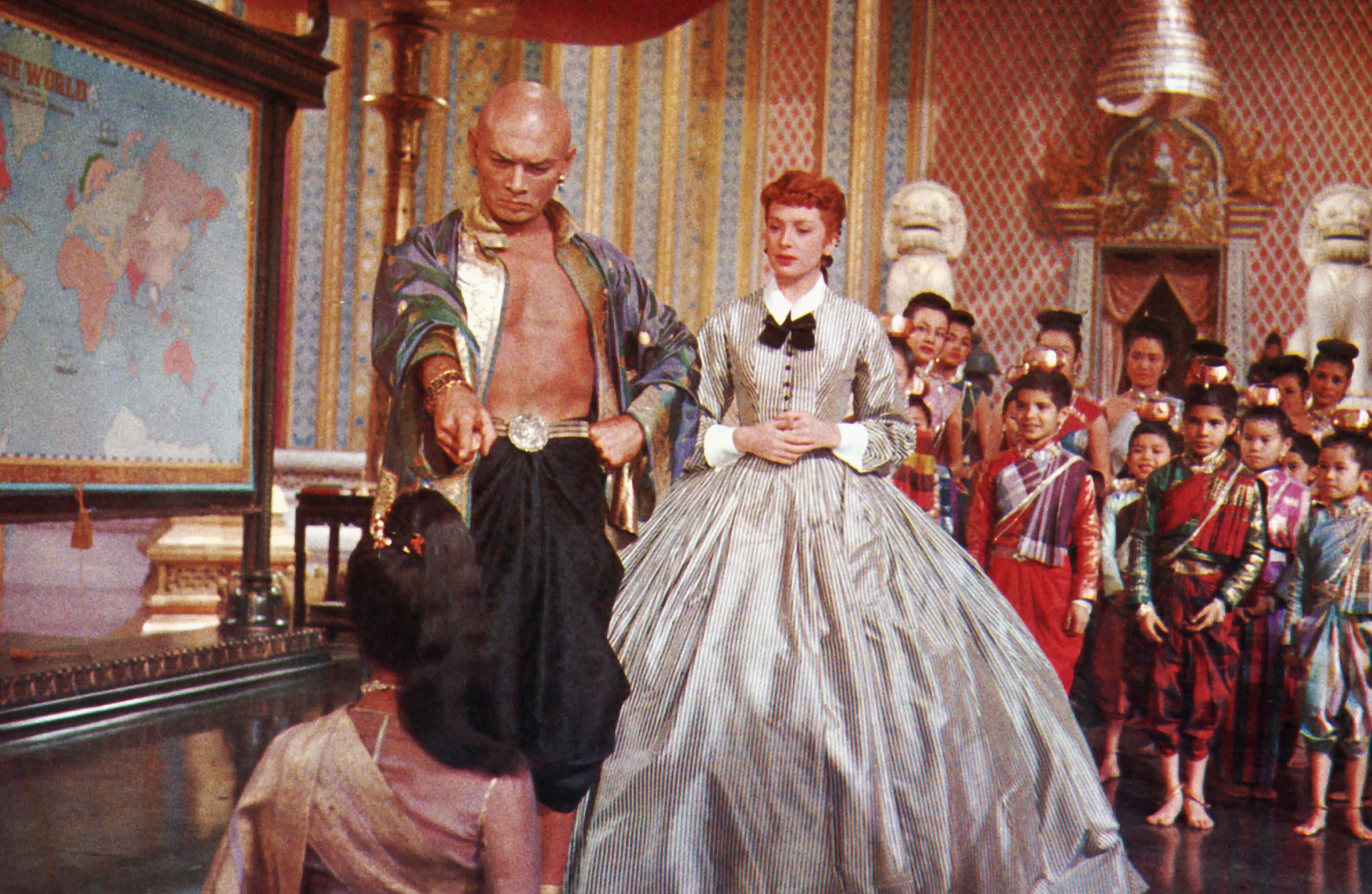

The King and I

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Walter Lang

Deborah Kerr

Yul Brynner

Rita Moreno

Martin Benson

Terry Saunders

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

In 1862, Anna Leonowens, a young, widowed English schoolteacher, arrives in Bangkok, Thailand, with her son Louis, having accepted a job teaching English to the children of the King of Siam. Greeted by the king's stern prime minister, the Kralahome, and his half-naked minions, Anna puffs up her courage. After the Kralahome informs her that she is to live in the palace rather than being granted her own home as previously promised, the plucky Anna charges into King Mongkut's chambers just as the graceful Tuptim is being presented as a gift from the Prince of Burma. When the king refuses her an audience, Anna unceremoniously charges forward. Although entrenched in tradition, the imperious king sincerely desires to usher his country into the modern era of scientific enlightenment, and so decrees that Anna should also teach his bevy of wives. Charmed by Mongkut's myriad children, Anna agrees to stay even though the king refuses her request of a house. Curious about this Western woman, the king's wives, led by Lady Thiang, the Number One wife who learned English from the missionaries, address Anna as "Sir," because her knowledge of science places her above the status of a "lowly woman." When the wives deride Tuptim because she longs to be with her lover, Lun Tha, rather than the king, Ann fondly recalls her beloved late husband. To spite the king, Anna teaches her pupils songs and proverbs about houses and honor. When Anna introduces a new map of the world challenging the supremacy of Siam, the children rebel until the king appears and admonishes them to take advantage of their education. Later, Prince Chulalongkorn, the heir to the throne, impugns Anna when she criticizes slavery, an institution that is embraced by his country. Late one night, the king summons Anna to take his dictation of a letter to President Lincoln. Mongkut, reclining, proclaims that no subject's head may be higher than his, and so orders Anna to lower hers. As Anna sweeps out of the palace, she comes upon Lun Tha, pining for Tuptim. Touched, Anna arranges a meeting between the lovers, and Lun Tha promises he will return one day to free Tuptim. Troubled by reports of English imperialism, the king becomes incensed when Anna's pupils persist in singing "Home Sweet Home." When the king asserts that Anna is his servant, she resigns and runs out of the room in tears. Afterward, Lady Thiang pleads with Anna to help guide Mongkut, who is apprehensive over rumors that the British regard him as a barbarian and hence intend to overthrow his kingdom and turn Siam into a protectorate. Swallowing her pride, Anna goes to the king and offers her help. Upon discovering that the British ambassador, accompanied by his aide, Edward Ramsay, is coming to Siam, Anna, an old sweetheart of Ramsay, suggests staging a sophisticated banquet in honor of their guests. In gratitude, the king finally promises her a home of her own. At the banquet, Tuptim narrates The Small House of Uncle Thomas , a play about an innocent girl, the victim of the evils of slavery. After the play comes to an end, Tuptim condemns slavery and is about to plead for her own freedom when the king snaps his fingers and the room breaks into applause. By the time the audience calls for the play's author, Tuptim has disappeared. After the British leave that evening, the king gives Anna one of his rings in appreciation of her efforts. When she challenges his right to keep a harem, he retorts that while women must remain faithful, men are entitled to a plentitude of wives. Anna replies that in reality, one man can love only one woman, and then recalls her first dance and invites the king to dance with her. They swirl around the room, but their mood of merriment is shattered by the news that Tuptim has been found running away with Lun Tha. For her dishonor, the king orders Tuptim beaten, and Anna charges that he never loved anyone and never will. Taking the whip into his own hands, the king is about to strike Tuptim when he crumples and runs from the room. When the Kralahome then accuses Anna of destroying the king, she announces that she will leave on the next boat and hands him the ring to return to Mongkut. Several weeks pass, and on the night that Louis and Anna are to sail, Lady Thiang appears with news that the king is dying, having shut himself away, refusing to eat or sleep since the banquet. After the prince states he does not want to be king and begs for Anna's help, Lady Thiang hands her a letter written by the king. When Anna reads the letter, which voices the king's deep gratitude and respect, she breaks into tears and hurries to visit him on his deathbed. As the king hands her the ring once more, his children beg Anna not to leave them in darkness, and when the ship's horn sounds, Anna sends Louis to tell the captain to return their luggage. Passing his title to the prince, Mongkut asks Chulalongkorn what his first act as king will be. After issuing a proclamation against bowing to the king, Chulalongkorn declares that his subjects should look upon each other with a kindness of spirit. Satisfied that he is leaving his kingdom in capable hands, the king quietly dies.

Director

Walter Lang

Cast

Deborah Kerr

Yul Brynner

Rita Moreno

Martin Benson

Terry Saunders

Rex Thompson

Carlos Rivas

Patrick Adiarte

Alan Mowbray

Geoffrey Toone

Yuriko

Marion Jim

Robert Banas

Dusty Worrall

Gemze De Lappe

Thomas Bonilla

Dennis Bonilla

Michiko Iseri

Charles Irwin

Leonard Strong

Irene James

Jadin Wong

Jean Wong

Fuji Levy

Weaver Levy

William Yip

Eddie Luke

Josephine Smith

Marie Tsien

Mary Lou Clifford

Grace Matthews

Kathleen Shoon

Judy Dan

Nephru Malouf

Margaret Fukuda

Stella Lynn

Lydia Wolf

Maureen Hingert

Jocelyn Lew

Jerry Chien

Nancy Chien

Yvonne Garosin

Dick Hong

Linda Hong

Warren Hsieh

Daro Induye

Candace Lee

Warren Lee

Jeanette Leung

Russell Ung

Rodney Yee

Virginia Lee

Stephanie Aranas

Evelyn Rudie

Dale Ishimoto

Amir Farr

Alladin Soufi

Leo Abbey

Henry Fong

Alice Uchida

Misaye Kawasumi

Shirley Nishimura

Kanna Ishu

Valentina Oumansky

Crew

Robert Russell Bennett

Mrs. Boonuam Boonsaith

Charles Brackett

Ken Darby

John De Cuir

Warren Delaplain

Leonard Doss

Eli Dunn

Paul S. Fox

Lorry Haddock

Oscar Hammerstein Ii

Ray Kellogg

Ernest Lehman

Gus Levene

Hal Lierley

Bernard Mayers

Michiko

Alfred Newman

Marni Nixon

Ben Nye

John Howard Payne

Edward B. Powell

Trude Rittman

Jerome Robbins

Richard Rodgers

Walter M. Scott

Leon Shamroy

Irene Sharaff

Robert Simpson

Helen Turpin

E. Clayton Ward

George Westenhiser

Lyle R. Wheeler

Darryl F. Zanuck

Videos

Movie Clip

Film Details

Technical Specs

Award Wins

Best Actor

Best Art Direction

Best Costume Design

Best Score

Best Sound

Award Nominations

Best Actress

Best Cinematography

Best Director

Best Picture

Articles

The King and I

The King and I had been a Broadway phenomenon, defying conventional notions of what made a musical a hit to present the story of two people in love, a widowed British governess and a polygamous Siamese king, who barely touched and never kissed. And just to make the proposition even riskier, Hammerstein's script ended with the King's death (of a broken heart), a rarity for the musical theatre.

The play had been written as a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence, a stage legend who had never quite caught on in the movies. Nonetheless, as part of her contract, she had first refusal on the lead in any film version. Sadly, that was not to be, as she was diagnosed with cancer during the run and passed away in 1952.

There was no question that 20th Century-Fox would produce the film version. The studio already owned the screen rights to Anna and the King of Siam, the historical book on which the musical had been based. Their 1946 film version had starred Irene Dunne, now retired from acting (though she certainly could have sung the role) and Rex Harrison. When Rodgers and Hammerstein were casting the stage version, they actually approached Harrison about playing the lead, whose songs were as much spoken as sung (years before Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe developed a similar style to fit Harrison's vocal range in My Fair Lady, 1964), but he had other commitments. Alfred Drake, the leading male singing star on Broadway at the time, had the same problem, so the songwriters started a series of open calls.

Harrison, Noel Coward, Marlene Dietrich and Mary Martin have all taken credit for what happened next, though the Martin connection seems the most feasible. She felt that her co-star from the musical Lute Song was perfect for the role. Yul Brynner was an accomplished singer and actor, but with few prospects for a man with his exotic looks, he was focusing on directing. Martin started working on Rodgers and Hammerstein, while she and Brynner's wife, former actress Virginia Gilmore, started nagging him about auditioning. Finally, he agreed to try out. He showed up scowling, sat on the floor and accompanied himself on the guitar as he sang a nonsense song he'd invented that sounded vaguely Oriental. And a star was born. Brynner had so little faith in his abilities, he didn't quit his day job. He took an eight-month leave of absence from CBS, where he was working as a director. Even after he scored a hit in the show, winning every award for musical performers on Broadway, and played a major role in Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1956), he returned to CBS.

At this point, however, he was so heavily identified with the role of the King that there was no other choice for the film version. Nonetheless, when Fox came calling, he turned them down at first, even suggesting that he would rather direct the film with Marlon Brando playing his role. When they persisted, he held out for script and cast approval on top of the $300,000 fee and percentage of the profits they were already offering. And he got it.

Meanwhile, the studio was trying to decide who should be cast as the "I" in The King and I. At first, they considered mostly singers, including television star Dinah Shore. Maureen O'Hara was all but signed when she made the mistake of sending them a recording of her singing Rodgers and Hammerstein songs. Rodgers listened, agreed she had a fine voice, and then said, "No pirate queen is going to play my Anna!" Finally, Brynner, who had met Kerr during the Broadway run of Tea and Sympathy, suggested her for the role. Although they would have to dub her singing, she had the British bearing, the talent and the marquee value to make the film work.

Kerr was touring in Tea and Sympathy when she won the role. At each city on the tour, she hired a vocal coach to polish her singing technique. Although she never expected to record the score herself, she wanted to be able to do the lead-ins herself. She did so well, in fact, that the studio kept her versions of "Whistle a Happy Tune" and "Shall I Tell You What I Think of You," although the latter was cut for fear it would make the character sound too whiny. The rest of her singing was supplied by Marni Nixon, a classical soprano in her early twenties who would later dub for Natalie Wood in West Side Story (1961) and, most notoriously, Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. Nixon's first challenge was matching Kerr's voice, which meant singing lower in her range than was comfortable. To help, the sound department used a special filter to enhance her lower tones. She also rehearsed the staging of each number with Kerr, matching her every move and facial expression to bolster the illusion that the character was really singing. The result was one of the best dubbing jobs in film history.

Brynner and Kerr got along beautifully during filming, which was good for her, as she was saddled with period gowns that often weighed over 40 pounds, causing her to lose 15 pounds during filming (she referred to herself as "The Melting Miss Kerr"). He was much harder on the rest of the production team, clashing openly with producer Charles Brackett and director Walter Lang. He used his script approval rights to keep studio executives from changing the ending so that the King would be gored by a white elephant. In addition, he added little touches that deepened the relationship between the king and Anna, often telling Lang what to shoot and print so that little looks and touches created a stronger sense of romance than had existed on stage. Little wonder when both he and the director won Oscar® nominations, Kerr sent Brynner a joking telegram: "A WELL DESERVED DOUBLE VICTORY. NOT ONLY ARE YOU A MARVELOUS ACTOR BUT A MARVELOUS DIRECTOR" (Quoted in Robbins, Jhan, Yul Brynner: The Inscrutable King).

The King and I was a huge hit for all concerned. Filmed for $6.5 million (ten times the cost of the original Broadway production), it grossed $21.3 million in the U.S. alone. It won Oscars® for Brynner, Best Score, Best Art Direction, Best Costumes and Best Sound, along with nominations for Best Picture, Actress (Kerr), Director and Cinematography. It would be re-made as an animated musical in 1999, with Miranda Richardson and Martin Vidnovic voicing the leads, and the non-musical Anna and the King (1999), starring Jodie Foster and Chow Yun-Fat), and inspire a short-lived television series starring Brynner and Samantha Eggar and the offbeat comedy The Beautician and the Beast (1997), starring Fran Drescher and Timothy Dalton. In addition, Brynner would return to the musical on stage for years, eventually turning in 4,000 performances as the King. With its success on stage and screen, it has become one of the most profitable musicals of all time, earning its backers in excess of $6.5 billion.

Producer: Charles Brackett

Director: Walter Lang

Screenplay: Ernest Lehman

Based on the musical by Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rodgers and Anna and the King of Siam by Margaret Landon

Cinematography: Leon Shamroy

Art Direction: Lyle R. Wheeler, John De Cuir

Music: Richard Rodgers, Alfred Newman, Ken Darby

Cast: Deborah Kerr, (Anna Leonowens), Yul Brynner (The King), Rita Moreno (Tuptim), Martin Benson (Kralahome), Terry Saunders (Lady Thiang), Rex Thompson (Louis Leonowens), Carlos Rivas (Lun Tha), Alan Mowbray (British Ambassador).

C-133m. Letterboxed.

by Frank Miller

The King and I

Ernest Lehman (1915-2005)

Born on December 8, 1915 in New York City, Lehman graduated from New York's City College with a degree in English. After graduation he found work as a writer for many mediums: radio, theater, and popular magazines of the day like Collier's before landing his first story in Hollywood for the comedy, The Inside Story (1948). The success of that film didn't lead immediately to screenwriting some of Hollywood's biggest hits, but his persistancy to break into the silver screen paid off by the mid-'50s: the delicious Audrey Hepburn comedy Sabrina (1954, his first Oscar® nomination and first Golden Globe award); Paul Newman's first hit based on the life of Rocky Graziano Somebody Up There Likes Me; and his razor sharp expose of the publicity world based on his own experiences as an assistant for a theatre publicist The Sweet Smell of Success (1957).

Lehman's verasitily and gift for playful dialogue came to the fore for Alfred Hitchcock's memorable North by Northwes (1959, his second Oscar® nomination); and he showed a knack for moving potentially stiff Broadway fodder into swift cinematic fare with West Side Story (1961, a third Oscar® nomination); The Sound of Music (1965); Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966); and Hello, Dolly! (1969, the last two being his final Oscar® nominations for screenwriting).

Lehman took his turn as a director when he adapted Philip Roth's comic novel Portnoy's Complaint (1972) for film, and despite some good reviews, it wasn't a commercial hit. He wrote just two more screenplays before retiring: an underrated comic mystery gem for Hitchcock Family Plot (1976); and the big budget Robert Shaw espionage drama Black Sunday (1977). Lehman served as president of the Writers Guild of America from 1983-85. After going zero for five with his Oscar® nominations, the Academy made it up to him in 2001, by presenting him with an honorary Academy Award for his "body of varied and enduring work." Lehman is survived by his wife Laurie and three children.

by Michael T. Toole

Ernest Lehman (1915-2005)

Quotes

Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera!- King

When I sit, you sit. When I kneel, you kneel. Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera!- King

You will order the finest gold chopsticks.- King

Your Majesty, chopsticks?- Anna

I make mistake, the British not scientific enough to know how to use chopsticks.- King

...Pairs of male elephants to be released into the forests of America. There it is hoped that they will grow in number and the people can tame them and use them as beasts of burden.- King

But your majesty, I don't think you mean pairs of MALE elephants.- Anna

Help also Mrs. Anna to keep awake for scientific sewing of dresses, even though she be only a woman and a Christian and therefore unworthy of your interest!- King

Your Majesty!- Anna

A promise is a promise! Head must not be higher than mine! A promise!- King

Trivia

Deborah Kerr's singing was dubbed by Marni Nixon.

Although this movie was filmed and promoted in the then-new 55mm CinemaScope 55, it was actually shown in the standard 35mm CinemaScope, with 4-channel stereo rather than the 6-channel stereo originally promised. CinemaScope 55 was never used or promoted again after this production.

At one point, Fox executives suggested that the story be changed so that the King would be gored by a white elephant, rather than become ill because of a personal humiliation.

Dorothy Dandridge was the original choice for the role of Tuptim, but turned it down. The role later went to Rita Moreno.

In Thailand (previously called Siam) the Royal family is held in very high esteem. The King and I is banned in Thailand due historical inaccuracy and perceived disrespect of the monarchy. The real Prince Chulalongkorn grew up to be an especially good king and led the way for modernization, improved relations with the west, and instituted many important cultural and social reforms in Thailand.

Notes

The film's title card reads "Darryl F. Zanuck presents Rodgers and Hammerstein's The King and I." The story of The King and I was based on incidents in the lives of the real Anna Leonowens and King Mongkut of Siam. For additional information about the real people and historical background, please see the entry for Anna and the King of Siam in AFI Catalog of Feature Films, 1941-50. A 1987 Los Angeles Times news item noted that The King and I was banned in Thailand because Prince Diskul, King Mongkut's grandson, was offended by Yul Brynner's portrayal of his grandfather, stating that "we don't think our king is like that, jumping around and so forth."

According to a March 1954 Daily Variety news item, producer Charles Brackett was to collaborate with Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II on the King and I screenplay. The extent of their contribution to the released film has not been determined, however, and the Twentieth Century-Fox Produced Scripts Collection at the UCLA Arts-Special Collections Library contains no scripts authored by them. Memos from Darryl F. Zanuck contained in a modern source reveal that Zanuck strongly argued that the film should not run longer than 135-140 minutes. To accomplish this, Zanuck suggested cutting the ballet The Small House of Uncle Thomas and eliminating some of the musical numbers from the stage play. In a memo contained in the Produced Scripts Collection, Hammerstein countered that the ballet could be shortened, but pleaded that it not be cut out. As a result, the ballet was cut from its original stage running time of fifteen minutes.

Other numbers cut from the Broadway musical were "My Lord and Master," "The Royal Bangkok Academy," "Western People Funny" and "A Woman Is a Female." Although strains of "I Have Dreamed" are heard in the score just before "We Kiss in a Shadow," the song was not in the film. According to the Daily Variety review, the major dramatic difference between the stage and film versions was the deepening of the relationship between "Anna" and "the King."

According to the Twentieth Century-Fox Records of the Legal Department, also contained in the UCLA Arts-Special Collections Library, Dorothy Dandridge was initially cast as "Tuptim." Studio publicity adds that Marisa Pavan tested for that role. Although Hollywood Reporter news items add June Tsukina, Hari, Elena Beatti, Don Takeuchi, Billy Lee, George Lee, Anita Dano and Florita Romero to the cast, their appearance in the released film has not been confirmed. An August 1955 Hollywood Reporter news item announced that June Graham was to act as assistant choreographer, but the extent of her contribution to the released film has not been determined. Jerome Robbins choreographed both the Broadway and film versions of The King and I. Brynner, Terry Saunders, Patrick Adiarte and Thomas and Dennis Bonilla reprised their Broadway roles for the film. The Bonilla twins were the real-life children of Lydia Wolf, who played one of the royal wives. A November 1956 Hollywood Reporter news item noted that dancer Gemze de Lappe sued Fox because the company denied her screen credit. The outcome of that suit is unknown; however, de Lappe is not credited onscreen.

Studio publicity contained in the film's production files at the AMPAS Library yields the following information about the production: The studio had to rent extra generators from M-G-M and Columbia to produce enough light to illuminate the palace courtyard set. Kerr's costumes weighed between 32 and 42 pounds. The dress she wore during the "Shall We Dance" number featured a metal hoop with a 25-foot circumference.

The film won the following Academy Awards: Best Scoring of a Musical Picture, Best Sound Recording, Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design and Best Actor (Brynner). The King and I propelled Brynner to stardom. The film was nominated for the following Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actress (Kerr), Best Direction and Best Cinematography. Although the film was shot in 55mm, like Carousel, it was projected in 35mm. In 1961, the studio converted the 55mm negative to 70mm, dubbed the process "Grandeur 70," and screened the film in Los Angeles on May 9, 1961, according to a Hollywood Citizen-News news item. After the film received a lukewarm reception in Los Angeles and San Francisco, however, the studio abandoned the idea of reissuing it, according to a July 1961 Hollywood Reporter news item.

Leonowens' story was first filmed in 1946 by Twentieth Century-Fox as Anna and the King of Siam, starring Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison and directed by John Cromwell (see AFI Catalog of Feature Films, 1941-50) The story later resurfaced as a CBS television series, Anna and the King, which starred Brynner and Samantha Eggar and ran from 17 September-December 31, 1972. In addition to playing the role of the king in the television show, Brynner reprised the role in Broadway revivals and road company performances until his death in 1985. In 1999, Morgan Creek Productions produced an animated film based on the musical titled The King and I, featuring the voices of Miranda Richardson and Martin Vidnovik, and in 1999, Fox 2000 Pictures released a non-musical version of the story titled Anna and the King, starring Jodie Foster and Chow Yun-Fat and directed by Andy Tennant.

Miscellaneous Notes

Voted Best American Musical (Lehman) by the 1956 Writer's Guild of America.

Voted One of the Year's Ten Best Films by the 1956 New York Times Film Critics.

Voted Outstanding Achievement in Film Directing (Lang) by the 1956 Director's Guild of America.

Released in United States Summer July 1956

Released in United States on Video September 13, 1990

Released in United States September 1991

Released in United States 1998

Shown at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) as part of program "Twentieth Century Fox and the Golden Age of CinemaScope" July 3 - August 15, 1998.

Initial domestic release was 35mm; 1961 re-release was in Grandeum 70mm.

CinemaScope 55

Grandeum 70

Released in United States Summer July 1956

Released in United States on Video September 13, 1990

Released in United States September 1991 (Shown in Los Angeles at the Hollywood Bowl September 20 & 21, 1991.)

Released in United States 1998 (Shown at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) as part of program "Twentieth Century Fox and the Golden Age of CinemaScope" July 3 - August 15, 1998.)

Voted Best Actor (Brynner) and One of the Year's Ten Best American Films by the 1956 National Board of Review.