Trigger Warning: The article below mentions physical violence and sexual abuse.

The Big Picture

- Haneke's The White Ribbon subtly connects pre-WWI village brutality to the rise of Nazi Germany, urging viewers to remember history's lessons.

- Through stark black-and-white cinematography and chilling implied violence, Haneke creates a dread-filled atmosphere in The White Ribbon.

- The film's exploration of systemic evil, spanning from children to adults, serves as a poignant reminder of the ongoing legacy of Nazism.

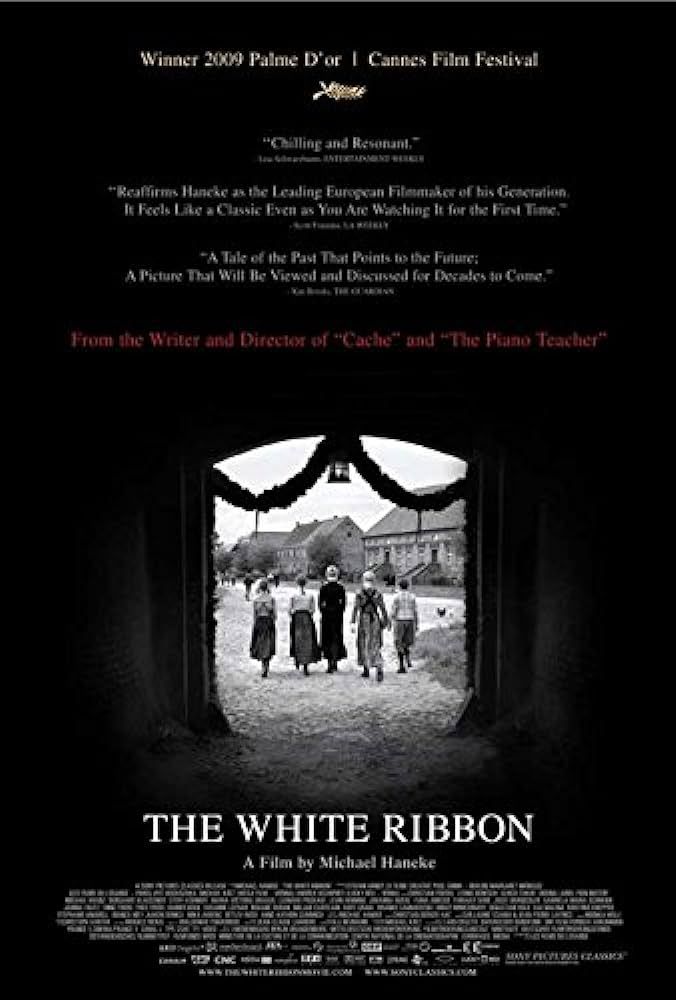

After his unofficial semi-retirement, Michael Haneke has stepped back from the spotlight, quietly falling off the radar. But lest we forget that he was a defining figure of 2000s cinema. One of his greatest achievements is his back-to-back triumph at the Cannes Film Festival, winning two Palmes d'Or in a row. The first of these victories went to his 2009 film The White Ribbon, which deserves extra attention and reappraisal after the major success of last year's Holocaust drama The Zone of Interest. In many ways, The Zone of Interest is a spiritual successor to The White Ribbon, but Haneke takes Zone director Jonathan Glazer's creepy dissociative filmmaking even further, right to where the audience is seated.

The White Ribbon

Strange events happen in a small village in the north of Germany during the years before World War I, which seem to be ritual punishment. Who is responsible?

- Release Date

- October 6, 2009

- Director

- Michael Haneke

- Cast

- Christian Friedel , Ernst Jacobi , Leonie Benesch , Ulrich Tukur , Ursina Lardi , Fion Mutert

- Runtime

- 144

- Main Genre

- Drama

- Writers

- Michael Haneke

- Studio

- Wega Film

What Is 'The White Ribbon'?

If The Zone of Interest can be called a Holocaust drama, then The White Ribbon is a pre-Holocaust drama. Set a year prior to WWI, The White Ribbon takes place in a fictional, agricultural German village, where a series of mysterious, deadly pranks is happening. Villagers live under the iron fist of a few patriarchal figures. One of them is The Pastor (Burghart Klaußner), who punishes his children's minor transgressions by publicly berating them, caning them, and tying white ribbons to their arms. As the village's kindhearted Teacher (Christian Friedel) begins to suspect the children as the culprits of the crimes, he soon finds that evil is top-to-bottom, and there is no justice in a rotten system.

Directed by an Austrian, The White Ribbon was entirely shot in Germany and spoken in German. After a somewhat minor controversy, the film ultimately represented Germany at the Oscars, and successfully garnered a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, alongside another one for Best Cinematography. Its nominations are richly deserved, as the starkly contrasting, black-and-white photography of the film only highlights the sense of didactically moralizing attitudes of the village. Michael Haneke was an early proponent of digital cinematography with his HDCAM film Caché, and while The White Ribbon was his last film shot on celluloid, the film's bright and sharp aesthetic certainly speaks to a modern sensibility unlike lush, nostalgia-hazed period films. Glazer would later take this approach to even more contemporaneous urgency, by giving his Zone of Interest a digital, reality TV-inspired look.

Haneke Hides the True Evil of 'The White Ribbon' in the Audience

Yet the cinematography isn't even the most stunning aspect of The White Ribbon. The White Ribbon is narrated by The Teacher after the fact, voiced by an older actor. This omniscient device places the film's perspective at least a few decades later, and we all know what happened in Germany in the 1930s to '40s. The most remarkable thing about the film is that the children will all grow up to become the adults of Nazi Germany, and this fact is entirely unpronounced by Haneke – he doesn't need to pronounce it. The audience's chilling knowledge of Nazism makes the entire experience of watching the film dread-filled; it's like a trainwreck you know is coming. Glazer's approach is to place the evil of the Holocaust behind a wall, using implication to feed the audience's imagination; Haneke takes it one step further and places it directly in the audience's auditorium, feeding on our prescient knowledge. He strikes a direct conversation with us, engaging us throughout what is otherwise a banal drama of domestic affairs. The "show, don't tell" mantra of Hollywood filmmaking has led to voiceovers largely being frowned upon, yet Haneke finds a way to use it with ample, potent meaning.

Like Glazer, Haneke uses implication as well. One of the early examples of violence is when The Pastor canes two of his older children for staying out late. His verbose lecture is depicted; the child getting his cane is tracked. Yet when the caning actually happens, Haneke hides it behind a door, only implying it through sound. Much like in The Zone of Interest, this aural implication is even more effective than direct depiction; whereas fully-fledged exhibition can desensitize us to violence, implication forces us to fill in the blank space with our imaginations and thus, fully reckon with the violence. Another similarity to The Zone of Interest is exposing the hypocrisy of the adults. Glazer shows his Auschwitz commandant Höss (coincidentally also played by Christian Friedel) having sex with the people he wants to exterminate, while Haneke cuts from The Pastor admonishing his child for masturbating to another patriarch committing sexual violence. Again, Haneke uses filmmaking tools to suggest his point, forcing us to make the connection.

Michael Haneke Suggests a Theory for Evil

Where did the children get their evil from? It was not born out of thin air, and Haneke traces it back to their parents' generation. While most WWII films are content with depicting Nazis as absolute evil, almost like an alien entity, Haneke reveals their systemic roots. Living under widespread oppression, where verbal and physical violence are commonplace, the children resort to violence as an outlet. Their behavior is punished by even more violence, forming a vicious cycle. After watching The White Ribbon, it's not hard to infer where Holocaust architects got the idea of branding prisoners from – their parents did it to them. The village's patriarchs frequently guilt-trip, lecture, and berate their children with absolute condescension and zero trust; it is not a parent's dialogue with their children, but a tyrant's to their subjects. Later in life, the children would speak the same way as Nazi officials to their oppressed. And when evil is systemic, carried over from generation to generation, it is not isolated. When it is entrenched in the plainest, metaphorical setting of a countryside village, it is ubiquitous. The evil of Nazism is not unique to its era, and did not miraculously disappear after WWII, especially not after generations of people living with it. That means it is still living with us, as seen in Holocaust denial, the continued rise of rightwing neofascism, authoritarian regimes, and genocides still taking place. By establishing this almost hereditary linkage of evil, Haneke urgently reminds us not to forget the past.

Systemic is the quality Haneke rightfully exposes, not just in physical violence, but in the entire operations of the village. Too many films are eager to pretend injustice is an isolated case, and once a villain is defeated, the goodness of the world is restored, and the system can be trusted. But that is not how the world works. The Pastor accuses the children of staying out too late, when we were shown the children visiting a wounded doctor's family out of care. He did not listen to or even allow his children to defend themselves, sentencing them to immediate punishment, and it's this sense of oppressive injustice that pervades the film, even more awful than the bursts of violence. Do things fare better for adults? When The Teacher finally gathers compelling evidence about the children's complicity, the children play dumb and gaslight him into thinking he's crazy. When he presents them to The Pastor, The Pastor threatens to report him for daring to commit the moral atrocity of slandering respectable children. The Teacher has been the only sensitive soul throughout the film, acting as an audience surrogate peering into the village, and by the end of the film, he is totally defeated by this wall of unreasonable tyranny. From children to adults, no one can escape the systemic, oppressive culture of authoritarianism. There is no pretense of triumph over evil, as the solution presented to us is The Teacher leaving town once and for all.

‘The Zone of Interest’ Takes Radical Detours From the Novel It Is Based On

Jonathan Glazer once again tackles adapting a novel for the big screen with his singular filmmaking sensibilities.This is not to mention sub-themes such as the culture of gendered violence against women and the Church's abuse of ideology to enact even more violence. Even within Haneke's filmography, The White Ribbon has become somewhat overlooked for its dryness, but under this plain-looking exterior, Haneke reveals tremendous insight into human nature. Like Glazer, he correctly identifies evil and abuse as systemic and institutional, and dares to make a theory about the origins of Nazism. It may not be a pleasant experience, but The White Ribbon is essential viewing.

The White Ribbon is available to rent or buy on Prime Video in the U.S.