Next June it will be 20 years since The Wire began its sprawling Dickensian portrait of Baltimore, Maryland, as a proxy for the decline and fall of the American empire.

Whatever happened to the cast? Dominic West went on to play Prince Charles in The Crown; Wendell Pierce took on Willy Loman in a London stage production of Death of a Salesman; Idris Elba starred in Luther, Thor and Cats; Michael K Williams burned brightly in Boardwalk Empire and others before his jarring death in September.

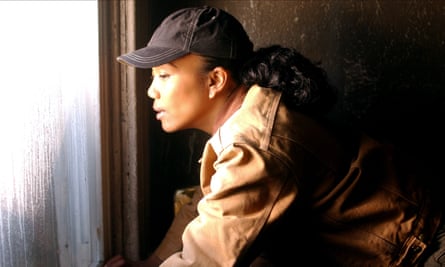

None, it seems, let Baltimore get under their skin as much as Sonja Sohn, who played police detective Kima Greggs – the first major portrayal of a Black lesbian on American television – on the trail of drug lords in the five-season drama.

Sohn cofounded ReWired for Change, a local outreach programme for at-risk youth, and made her directorial debut in 2017 with Baltimore Rising, which depicted the Black-majority city in the aftermath of the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray in police custody.

Now she returns there with The Slow Hustle, an HBO documentary that examines the 2017 death of Sean Suiter, a widely respected Black police detective fatally shot in the head while on duty. How, why and by whom has never been solved.

“I think of Baltimore as my soul home,” Sohn, 57, says by phone from North Carolina’s Outer Banks. “I consider Baltimore to be as much of a home to me as the place where I grew up in Virginia. I feel like the city is a reflection of my own psyche.

“Coming to the city was was kind of a reckoning with my own self. I think Baltimore does what it did to me and it’s a divine mirror. We don’t always like what we see but we need to see what’s in that mirror if we’re going to actually present truthfully in the world.”

The Slow Hustle starts with shocking footage of Suiter’s body being discovered (“Oh, my god!”, “Sean, no! Sean!”) in an alley in West Baltimore, an area notorious for poverty, segregation and violent crime. An independent review board ruled that the 43-year-old detective had in fact shot himself – a finding that his family and others vehemently reject.

Sohn is also sceptical. She comments: “Everybody walks away from the film seeing that the suicide implication is pretty serious and, if you’re going to imply that, then you’d better have really stiff, unshakeable evidence. I’m not sure the police have proven that.”

There are other theories. Suiter died just a day before he was due to testify before a federal grand jury investigating an elite Baltimore police unit, part of one of the worst law enforcement corruption cases in recent US history. Suspicions were aroused that a hit had been ordered to silence him.

D Watkins, a local journalist and author who shares the view that Suiter’s death could have been an inside job, says in the film: “What developed for me out of the whole story is this whole idea of Black lives really don’t matter. Like, even if you’re a police officer, they really don’t.”

The Slow Hustle contains interviews with Suiter’s widow and children, lawyers, politicians and investigative journalists, and Baltimore police including former commissioner Kevin Davis. There are poignant moments at the fallen officer’s graveside and at an anniversary vigil.

Underpinning it all is a Wire-style critique of institutions, in particular a police department so hollowed out by corruption that even the attempt to solve the death of one of its own is met with insurmountable doubts.

This malaise, Sohn points out, goes beyond Baltimore and policing in general. “For me this case, and the family’s position in this case, represent the microcosm of the macrocosm,” she says. “Right now we’re dealing on a mass level with this lack of trust of law enforcement because of the way they have treated Black folks. We are seeing multilayered corruption with new eyes as a culture.

“Here we have a case in which a cop has fallen and ultimately one of the major obstacles to solving this death, this mystery, this crime is the fact that the police can’t be trusted. The city knows that Suiter was going to testify against a group of corrupt cops and there is this history of corruption in the police department in Baltimore, then that lack of trust is amplified throughout this city.”

“So the first theory that folks are thinking is, ‘Of course you guys killed him’. That is the rumour that sweeps like a wildfire through the city and the fact that’s the first theory that erupts says something on a larger scale about what could happen if the police don’t get their act together and regain the trust of the people.”

Sohn adds: “To me, what Nicole [Suiter’s widow] and the family are going through is the microcosmic example of what is happening to all of us, that when public institutions and structures don’t get their act together, the people suffer and, in this instance, the family suffers.”

Sohn was at home in North Carolina when George Floyd, a Black man, was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis last year. But it brought back the visceral sensation of being in Baltimore for the uprising that followed the death of Gray. “I didn’t know how much I had been impacted by it physically until 2020 came and I saw the correlation,” she says.

With police reform stalled in Congress, and Republicans stoking fear of rising crime in major cities, does she believe the momentum of the Black Lives Matter protests can be sustained? “At this point, it’s a more nuanced game. I don’t think we’re losing momentum. In workplaces across the country, the culture is changing quite a bit. But there’s a lot of pushback of course.

“I’m sure those who are involved in policy making are in the midst of looking at how to develop a more nuanced strategy on some other levels because the folks who are in opposition are playing serious chess right now. They’re up in that supreme court and they are winning. It is not a good look.”

Sohn was born to an African American father and Korean mother who met after the Korean war. She grew up in Newport News, Virginia, had a stint in New York as a slam poet and recorded an album in London. She was, perhaps, a counterculture rebel and social justice activist before her time.

“I was like a serious punk in the ’80s,” she laughs. “I was railing when there was nobody railing with me. I was sitting up at CBGB’s [music club], the only Black girl with shaved hair, screaming, and I had a zine. I had my moment of doing all of that. I felt alone and I was happy.

“What really got me with the Baltimore Rising cast is I saw them speak at a museum and I was like, ‘Oh my god!’ I cried. I said, ‘Where were you? I’ve been waiting for you all my life and now you’re here and I’m an old lady.’ But let’s see what I can do. I can make a movie. I’m still worth something.”

The Slow Hustle is now available on HBO with a UK date to be announced