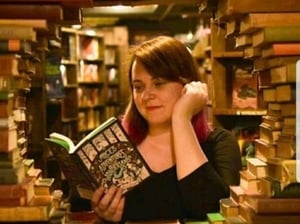

Dr. Caroline West is a sex educator and host of the Glow West podcast, which focuses on sex, sexuality, and the body. Here, she writes about how Baby Reindeer, the latest hit show from Netflix, has challenged society's perception of sexual assault and its victims.

New Netflix series Baby Reindeer has become a runaway success, largely because it captures the sheer horror of surviving not only sexual violence itself, but the increased risk of further violence due to the victims vulnerability after the fact.

It is also a holistic portrayal of trauma, providing viewers with a way of understanding the complex impact sexual violence has on victims. For many victim-survivors of sexual violence, the response they face when they tell their story is one that can erode their sense of self even further.

It takes a mountain of resources, courage, support, and work to survive this. Baby Reindeer's creator Richard Gadd did survive his own brush with sexual assault, which is the basis of this series, and his sheer bravery is clear in not only writing this show, but also acting in it.

Gadd's depiction of trauma and vulnerability gives viewers an astonishing glimpse into the reality of life after sexual violence. He tells his real life story through the character of Donny, a man who is stalked by a woman called Martha. Her actions send his world into chaos as she seeps into every aspect of his life and consumes his every thought.

Despite numerous instances of breached boundaries, Gadd's character struggles to speak up about Martha because her actions are not the sole violation he is struggling with. This is only further complicated by his experience of a broader lack of belief in male victims of sexual assault.

In this way, the show explores the complicated and often problematic reality of what society assumes a victim looks like, and what kind of victim we believe.

When we think of a victim of sexual violence we might picture many things, but most people picture a woman. In an Irish study about responses to victims coming forward, 80% of men felt that they would not be taken seriously and 77% thought they would be laughed at and blamed.

The connection between the fear of it happening and the fear of not being believed can be heightened when high profile cases make the news, with online commentators speculating on why the victim waited so long, what were their motives in coming forward, what were they wearing, and how many people they have slept with before some decided to enact violence upon them.

This can be why many people don't speak about their experiences to loved ones or professionals, as it is simply too much to deal with. In this context, the rawness shown by Gadd is breathtaking as he acts out his real life violations by multiple people.

For Irish viewers, Baby Reindeer can hit some sensitive nerves when it comes to the legacy of sexual trauma victim-survivors and how many of them have been treated in our country. We may recall the trial where a teenage girl's underwear was used as evidence against her in an alleged rape case.

At the time, protests highlighted the issue with how sexual abuse cases were being handled at large, with much of the focus being put on the appearance, behaviour, substance use, previous sexual history, race, or gender of the plaintiff.

The people who commit sexual violence or harassment are often framed as monsters, but this approach misses one very uncomfortable fact: people who harm others in this way are not always distant, unknown entities.

They can be our friends, our family members, our colleagues, our peers, our leaders, our communities, ourselves. They are people we may love and have previously had consensual sex with. They are people that are popular, loved, hated, famous, likeable, vulnerable, disgusting, respected, talented, human.

baby reindeer is truly one of netflix's greatest accomplishments: a gripping, multi-layered study on stalking and obssessions, but mostly an intimate (and somewhat funny) portrayal of how a cycle of lifelong abuse is powered by feelings of self-hate. a challenging must see. pic.twitter.com/6scQJqSCbM

— João (@joao_marques_05) April 28, 2024

Baby Reindeer's Martha is a sad figure at first. Outwardly presenting an image of success as a high flying lawyer who had acted as a consultant to prime ministers and celebrities, in reality she was a convicted stalker with repeated convictions and fixations, and a willingness to turn to violence.

Donny’s own vulnerability is slowly revealed, allowing us to understand why he didn't report it, why he connected with Martha, how he struggled with the fallout of her infliction of violence, and how his vulnerability was weaponised by her.

It's a perceptive depiction of how manipulation is often done so subtly that it is hard to name what is going on and find ways to escape the situation.

Baby Reindeer is the latest in a line of recent works that examine and challenge our preconceived ideas about the people who commit sexual violence and their victims. It stands on the shoulders of other groundbreaking creative works that offer us a different way to understand sexual violence and its impact.

Among them is Michaela Coel's series I May Destroy You, which offers a space for us to understand that sexual violence is indeed a spectrum, situated within the context of rape culture. Louise O’Neill’s novel Asking for It, also forces us to reflect on our ideas about the 'perfect’ victim who is more likely to be believed than a victim we don’t like.

Emerald Fennell's film Promising Young Woman is another example of the 'good for her’ approach to stories of sexual violence. This genre depicts a female protagonist righting a wrong, experiencing catharsis for what has been done to them, and finding an outlet for their rage. They are often framed as feminist films, although this is open to debate.

Baby Reindeer, and the above examples, offer some ways to authentically depict sexual violence on screen, and how to create space for victims to regain autonomy through other means than violence.

They demonstrate our lack of nuance in understanding what sexual violence looks like, but what they all have in common is reminding us that we all have a role to play in addressing sexual violence - no matter how big or small, and to lead with compassion.

If you have been affected by issues raised in this story, please visit: www.rte.ie/helplines.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.